Revisiting I Wanna Be The Guy

Ten years later, still trying to be the guy.

Today the idea of an "indie" game seems less and less appropriate. While there are exceptions, most popular independent games (sans the explosion of RPG-maker inspired software that's just... everywhere) are polished products with real budgets. This is opposed to a decade ago where independent games were rougher, played fast and loose with copyright issues, were fascinating derivatives of genres tropes, and truly felt like an alternative to gaming as opposed to a part of the norm.

Today the idea of an "indie" game seems less and less appropriate. While there are exceptions, most popular independent games (sans the explosion of RPG-maker inspired software that's just... everywhere) are polished products with real budgets. This is opposed to a decade ago where independent games were rougher, played fast and loose with copyright issues, were fascinating derivatives of genres tropes, and truly felt like an alternative to gaming as opposed to a part of the norm.

I Wanna Be the Guy is from this bygone era where independent games were really, truly, independent. Perhaps a bit too independent. Next to Barkley, Shut Up and Jam: Gaiden (which similarly requires a bit of genre savvy to appreciate), I Wanna Be the Guy is one of the all-time great parody games from this period of indie gaming. This is in spite of the game's intentionally unfair difficulty, to the point of being nearly unplayable.

I have specifically cited I Wanna Be the Guy as "postmodern." The term does get thrown around a bit, often for games that are usually more abstract or that truly frustrate the idea of playing a video game, usually in reference to games that are non-genre defined or lack determinate goals. I Wanna Be the Guy is far more discrete in its objectives as opposed to, say, Flower or Proteus -- both defining independent games where you do very little if anything. By contrast, I Wanna Be the Guy plays intentionally like a straightforward, old-school action game.

So then why do I consider I Wanna Be the Guy to be more forward thinking or at least more "postmodern" than games that are more avant-garde? We generally assume that post-modern thinking would influence a game to be more abstract or a non-genre game. This does not have to be the case. I Wanna Be the Guy is, rather than simply a genre neutral art-game, a correct post-modern deconstruction because it bends game logic by messing with the syntactic language of "playing a game." It screws with commonly accepted procedures that we often take for granted. The result is a game that is seemingly improvisatory because while the symbology of traditional games is present, it doesn't behave in expected ways. A more currently example is 2016's fantastic Undertale, although that game would merit an article on its own.

The game is also wicked funny and cruel.

Let's look at just the notorious first screen I Wanna Be the Guy the game:

One of two things will happen:

The player jumps down and immediately gets bulldozed by a spiked platform.

Accidentally jump up, revealing another screen.

The fact that this first screen is designed to be instantaneously lethal is the inversion of everything that good game design has informed over the last twenty years (assuming that early 80's arcade titles were often this punishing but perhaps less dramatic). The fact that there are no tells makes the establishment of rules on this first screen that much more frustrating. The only way to react to what is about to happen is to already know what will happen.

However, the patterns of the flying spike platforms then behave inconsistently. As you work your way down, the final platform comes from the opposite direction. Again, this inverts good game design. The rules are recognizable from other games (spikes=bad), and the spaces where platforms will crush you become obvious, but then it is not reliable enough because of the change in direction. In many ways, this screen sets the tone for the game perfectly. In I Wanna Be The Guy, what have been taught from other games is not reliable.

Consider then the second option for this first screen, jumping up. Now you are introduced to the game's most notorious enemy: the delicious fruit. The first couple falls predictably downward. However, when crossing back over some of the remaining fruit flies (heh) upward because everything you know about gravity is, apparently, a lie. The stakes are raised, the sheer lethality of this world is consistently startling. The game design is not based on accepted and established logic but rather on the basis that the most difficult possible outcome is what will happen (while still "beatable").

Consider then the second option for this first screen, jumping up. Now you are introduced to the game's most notorious enemy: the delicious fruit. The first couple falls predictably downward. However, when crossing back over some of the remaining fruit flies (heh) upward because everything you know about gravity is, apparently, a lie. The stakes are raised, the sheer lethality of this world is consistently startling. The game design is not based on accepted and established logic but rather on the basis that the most difficult possible outcome is what will happen (while still "beatable").

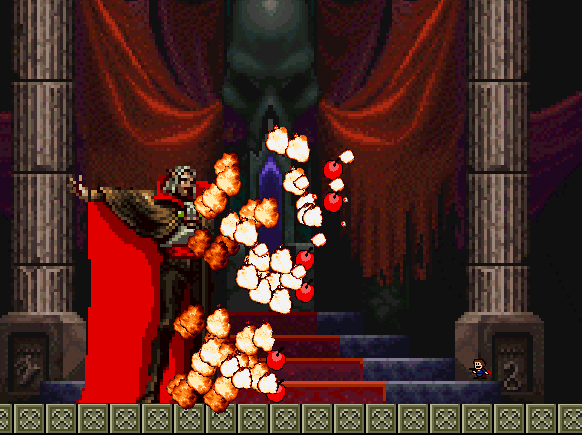

Then there are the parodistic elements. These moments (particularly bosses) incorporate the languages from other games... and then make it exaggerated and terrifying. Assuming you follow the path upward and survive the onslaught delicious fruit, you may encounter a game of Tetris. Odds are, most gamers are aware of the rules of Tetris. By incorporating this into the game, there is a completely foreign but familiar element that is now thrown into the game. Most of the bosses (Mike Tyson, Dracula, etc.) behave similarly to their external counterparts -- just substantially harder. So, while some of our learned experience can help us, it is, as established, not perfectly reliable. We have to constantly be on our toes and always assume the worst.

All of this corroborates why I Wanna Be the Guy is a smarter concept than even its creator may realize. Yes, it is still an elaborately frustrating prank. But, it's not nearly as frivolous or even brainless as the many games it spawned (or the masocore genre). The game works as a polyamorous amalgam of great games (and music!!), made of blatant thievery that is then reworked into something recognizable enough for us to be both frustrated and horrified when it kills us dead. It shows that the common syntax of game design can be taken for granted and abused in ways to make what should be straightforward unreasonably difficult.

As as result, I am far more scared of this fruit throwing Dracula than Castlevania's canonic one...

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like