Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Writer Jason Johnson ruminates on the application of religious symbolism to game design -- and issues a call to understand the essential forms that underpin design, rather than the surface appearances that are much more easily discussed and replicated.

[Writer Jason Johnson ruminates on the application of religious symbolism to game design -- and issues a call to understand the essential forms that underpin design, rather than the surface appearances that are much more easily discussed and replicated.]

Tetris can be interpreted in many ways. Because it is an exercise in pure abstraction, Tetris has invoked all sorts of explications regarding what it could imply. People have likened it to the rat race and communism, or to the stock market crash of 1987. And that's okay. That's how we make sense of things: we attach meaning to them.

For example, I can distinguish the constellation Orion from the arbitrary mass of stars because I envision it as a huntsman raising a cudgel overhead in victory, or as if to strike. Furthermore, I can recall the myths of Orion -- how his skillful hunting threatened to decimate all animal life until the gods unleashed a giant scorpion to kill him -- simply by looking at this arbitrary mass which otherwise lacks meaning.

To carry this line of thought to its conclusion, one could imagine that, in an ancient culture where these symbols held much more significance, when Spartans gazed at the stars, they saw not only a mighty huntsman, but a warning about the dangers of overhunting.

Tetris typically evokes modern interpretations. It's not a huge jump to draw a line from Tetris to the milieu sown by the politics of the U.S.S.R. in the '80s. Art and creative mediums have the tendency to soak up aspects of the environments they are created in.

One can certainly visualize Alexey Pajitnov tossing a Soviet rag in a trash bin at the Academy of Sciences, disconcerted by the Communist Party's insistence to perpetually inundate the military with funds, as he slipped off to his terminal to work on Tetris.

It's feasible that Tetris was influenced, ever so indirectly, by its times. After all, the election of Gorbachev a year later was the Jenga block that finally toppled the tower -- or height ten in Tetris, if you will.

But one shouldn't give this interpretation much credence, as its blueprint aligns as much with the events that began socialist rule in Russia as it does with the downfall of that government. In fact, the upheaval of the tsarist monarchy in 1917 makes for a straighter comparison. It's easy to liken the structure of Tetris to a society of impoverished serfs overburdened by the demands of their noble landlords.

Much like the commoners who were allowed a glimpse under the Iron Curtain as Gorbachev introduced reforms, the serfs of old Russia tasted the forbidden fruit of land ownership. This is precisely the moment that the aristocracy made that one fatal, unavoidable move which catapults a game of Tetris from a tense but manageable situation into a frenzied and ultimately fatal cascade of tetrominos.

This is very cold, mechanical analysis. It would be much less misanthropic to view a loss for the elite as a victory for everyone else. Fritz Lang's propaganda-laden masterpiece Metropolis, premiering just ten years after Russia's socialist revolution, takes this perspective.

Lang's yarn of a dystopia in which the grandeur of society is upheld by the suffering of machine workers again bears resemblance to "the relentless building block video puzzle," except this time the laborers fulfill the role of the player, the executive-kings are cast as the machinelike algorithm, and the blocks, the demand to fuel an expansive, expanding, futuristic city.

Yet the narrative skirts around the inherent catastrophe in Tetris, quelling a worker's revolt with a mere handshake between a noble and a serf, as if the computer emerged from the screen saying, "player, I will let you win me."

I could roll on and on with these interpretations, each seeming equally valid, yet each directly contrasting a fundamental aspect of the last. This is why I disagree with the concept of "truth in game design," which was proposed by Mr. Scott Brodie in a Gamasutra article that elaborates on some ideas of Chris Crawford, suggesting designers should "integrate rules into game systems so that they reveal something useful about the human condition."

While the designer is certainty free to do so, he must realize that he relinquishes all control of said game's interpretation to the player, unless he is creating propaganda like Fritz Lang, and even then the interpretations are numerous. The artist who does not impose his own interpretations avoids the label of pretension.

There's no inherent truth in games, at least not in the sense of submersed intentions, just as there's no huntsman in the cluster of stars that forms the constellation Orion. Interpretation is merely self-fulfilled imagination, each as valid and invalid as the next.

While one interpretation may come closer to the artist's intent, that doesn't by any means discount a feral interpretation. This lack of meaning seems to discredit the growing movement towards a more literary approach to analyzing games. If games are devoid of any definite truth aside from logical and mathematical ones, then why write about them?

Well, for entertainment... for persuading others to hold a belief through analogy... to convince ourselves that there's some underlying value to this habit that we sink our time/money/lives into....

But there is a greater purpose other than these somewhat trivial motivations. To look again at the Orion analogy, we can see how interpretations act as a framework which allows us to better focus on the subject at hand, just as patterns of stars are elusive until labeled as constellations. Furthermore, the constellations act as an astronomical map, so that we can locate meteors and planets and such.

As for game interpretations, they contextualize structures and physics and systems so that we can better hold their relationships in our mind to reflect upon them. They allow us to grasp concepts we ordinarily wouldn't. This is the true value of art and myth and religious metaphor, to make that which cannot be comprehended comprehensible through interpretation.

Yes, Tetris can be interpreted in many ways, and the reason for this is its abstractness allows its structure to be easily accessed and dissected. The transparency of its landscape, lacking any visual representation of the outside world, frees the mind to incorporeal things. Concepts such as perfection, the infinite, and divinity can almost be visualized.

Yet because of our terrestrial nature, farmed from the earth like mindless Pikmin, when we go to relate this knowledge, it somehow turns into, "Tetris exists as a virtual artifact signifying the end of the Cold War."

Tetris, with its multifaceted angles, reminds me of another attempt to relate the ineffable, the story of the Tower of Babel, taken from the book of Genesis as established from Jewish religious lore. The two share a few obvious outward similarities.

For one, it's not very unorthodox to interpret Tetris as a game about building a tower. Following the same logic, one could conclude that losing in Tetris replicates the fate of the Tower, an abrupt end to progression brought on by confusion.

The player can be seen as the foolhardy Babylonians, who against their better judgment conspired to build a structure to reach into heaven and rival God. God, who did not take too kindly to this idea, compares to the omnipotent forces of Tetris, which lie in its continuity. And, as I've alluded to, both the game and the myth have a metaphysical quality. Both contain mysteries.

It's the concepts that arise from the "facts" of the Tower of Babel myth that, through less obvious comparisons, give some insight into these mysteries.

These include the concept of man's unbridled ambition, demonstrated merely by the undertaking of the construction. Comparatively, this concept exists in Tetris's level structure, in how each height demands more and more skill from the player, and in how each step toward perfection pushes it further away.

These include the concept of man's unbridled ambition, demonstrated merely by the undertaking of the construction. Comparatively, this concept exists in Tetris's level structure, in how each height demands more and more skill from the player, and in how each step toward perfection pushes it further away.

On the opposite side of the coin is the theme of God's magnificence, revealed by the ease in which God thwarts man's best effort. God's magnificence can be interpreted as Tetris's eternal carrot-on-a-stick, which forever tempts the player to climb a few more lines into the atmosphere.

Then, there's the way God crushes the rebellion. He confuses the language of the Babylonians so they can no longer understand one another, which is where the story earns its reputation as a language creation myth. This confusion, this scrambling of language, can be compared to the randomness of the falling pieces, which the player must assemble to the ever-constricting demands of perfection.

These comparisons highlight some crucial elements of Tetris's structure.

The theme of unbridled ambition is conceived from Tetris's gradual and consistent increase in difficulty.

The theme of God's magnificence is conceived from Tetris's infinite field of play, which lacks an ending boundary.

There is also a theme of randomness as an obstacle, conceived from Tetris's randomization.

These three elements compose what I believe to be the root of Tetris's brilliance, but I don't expect you to take my word for it.

These elements exist in tandem not only in Tetris, but in many other games, and while not completely interchangeable, these games have enough in common to be mentioned in the same sentence. To show these elements are more than a one-hit wonder, and to provide evidence that their simultaneous occurrence constitutes an archetype, as well as for the sake of variety, other games will be discussed.

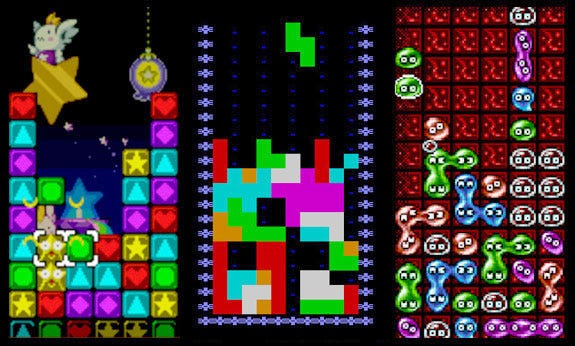

The most apparent Babelesque games are other action-puzzle games, many which are directly influenced by Tetris -- like Puyo Puyo, Puzzle League, and Meteos. While it's true that some of these games offer a wealth of modes, at their purest, they follow the Tower of Babel formula in that their difficulty gradually increases, they lack an end boundary, and they present randomness as an obstacle.

A less apparent but ripe example is the WarioWare series, Nintendo's metempsychosis simulator, which flings the player into random avatars in rapid succession. Full-fledged minigames, such as the Pyoro mini-games, including Bird & Beans, are offered alongside the main course i.e., the random, flitting state that is WarioWare.

These mini-games are simple in nature, and often riff on classic games, as Bird & Beans homages the Atari classic Frog Pond. I mention this because the shape of these minigames is often identical to that of the main game, insomuch as it is cast from the mold of Tetris and the Babel myth.

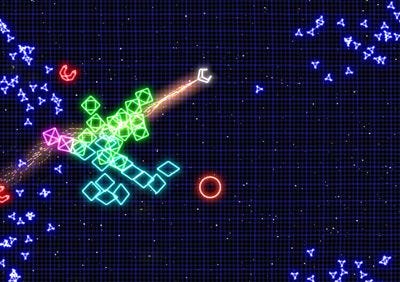

Geometry Wars: Retro Evolved shares this form as well, and in my mind is one of the greatest testaments to its merits. Geometry Wars unabashedly brought a classic arcade-style game into our current era, and did so to rousing success. While this feat isn't unparalleled, it does illustrate the staying power of the Babel archetype, a form which was likely born out of the early limitations of hardware and basic elements of design, yet remains the essential ingredient to some greatly enjoyed games today.

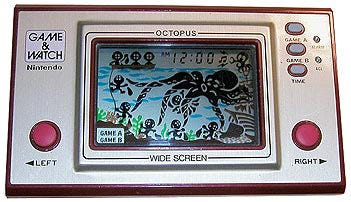

Actually, this can be said about all of the games I've mentioned. How many iterations of Tetris have come and gone over the years? And certainly WarioWare makes all sorts of winks and nods to Nintendo's Game & Watch line, a series which to my knowledge never strayed from the combination of increasing difficulty, infinity, and randomization.

Yet the issue isn't so much that these properties coexist across the spectrum of genres arising in our burgeoning yet still inchoate period of interactive media, but that their relationships matter. By labeling their relationships, we might realize a broader knowledge on design. The game industry often redefines itself through iteration, rather than in leaps and bounds. Once a truly well implemented idea is discovered, it's likely we'll be seeing it for at least the next decade.

In part, I attribute this to the elusiveness of design, to how it's hard to hold its elements in our minds, because they're, above all, abstract. That's why so many developers take the iterative, bottom-up approach to design. The top-down approach is too risky and too elusive to be commonplace. But writing is cheap, and if utopias of design can be realized anywhere, it's on the written page.

One curious aspect of the relationships at hand is that each element supports the next, even to the extent that the whole design would collapse under its own weight if one element were removed. I came to this conclusion by asking questions. Questions like: Would Geometry Wars play differently without randomization? What if WarioWare lacked its steadfast difficulty curve? What if Tetris could be won?

Most always, the answers point to the Babel archetype's integral design. In the following thought experiments, we will reflect upon these answers and, in effect, imagine what remains of a triangle as each side is removed.

To begin, try to imagine the archetype without the element of randomization, or, on second thought, try imagining Geometry Wars without the random appearance and placement of enemies. It's true that many shooters do forego the element of randomness.

Shooters like Gradius and R-Type are straightforward, designer-controlled affairs in which auto-scrolling, handcrafted levels put the player through the wringer. The motivation to play largely depends on these levels, in how they provide variety, both in their layouts and their artistry.

Geometry Wars has no such luxury. It transpires within a rectangle, purposely laden of all but the most rudimentary assets. It's only through lightly structured randomization that its levels are formed. Without randomization, the player would have little incentive to come back, as the game would be reduced to the rote memorization of Gradius, only lacking the level variety to keep players interested.

In this, we can see how the element of randomization upholds the element of the infinite, as randomization provides the level design on Geometry Wars' infinite plane. That's not to mention the impossibility of predetermined level design in boundless time, which would either result in an endless loop, or emptiness.

Moving on to the next question, the concern becomes the steady difficulty ramp and its relationship to other elements in Babel type games. In most all of these games, the difficulty is regulated by the game's structure.

The player crosses some tripwire, and things start moving a little faster. Challenges appear in places they hadn't before. This tying of difficulty to markers within a game allows the player certain opportunities. They allow him the chance to get his feet wet. They allow him a sense of accomplishment. They allow him to feel the game constricting his opportunities, as if the walls were slowly closing in on him.

In regards to WarioWare, which features a heavily structured difficulty scale, the scale does much more. It prevents the game from going haywire. WarioWare's difficulty scale regulates not only the speed and breadth of play, but also when more devious modes of play appear. The first tier of microgames are relatively straightforward, but they become progressively tricky in each subsequent tier. In this case, the difficulty scale keeps tabs on randomness, preventing it from running amok at the player's expense.

Similar forces can be seen at play in Geometry Wars, in the way chaos is initially constrained and, more specifically, in how top-tier adversaries such as Snakes and Repulsars only appear after the player has crossed certain thresholds.

Tetris's randomness doesn't need constraining. Only seven shapes can be formed from four contiguous squares, opposed to the multitude of micro-game variants found in WarioWare. Still, its difficulty curve and randomization have a supportive relationship.

In Tetris, randomness is a puzzle that must be solved in order to gradually progress the difficulty curve. This gives Tetris a sort of push-pull dynamic, in which the player is suspended between a state of pushing the difficulty scale higher and being pulled up the difficulty scale by the game. Removing the push from the equation would dismiss the paradox.

Another paradoxical component to Tetris is it cannot be won -- unless, of course, you happen to be Henk Rogers. But what if Tetris had a final height followed by scrolling credits and the words "The End"? Would it make a difference? Most definitely. Foremost, the "just one more round" factor would be sacrificed. Sure, it could still keep you entertained for weeks or months, and possibly even years... but decades?

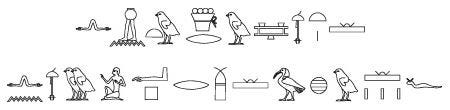

It's in its impossibility that Tetris's appeal ultimately lies. Tetris stimulates the insatiable thirst for perfection that has obsessed mankind since consciousness allowed. The saliva of religion, law, the arts, the sciences all flows to taste that which is forbidden -- no, impossible. Alas, to quote an ancient Egyptian proverb,

The limits of art are not brought. No artisan is equipped with perfection. - Ptahhotep c. 2300 B.C.

If Tetris did bow to a master, if its apex were to be reached, its concept of infinity would be lost, and, with it, its ideal of perfection, for infinity and perfection are yoked together in its reality. Perfection exists in how the pieces unite to complete and clear a row, and in how the rules require that gravity increase by x amount for every ten rows cleared; infinity exists in how the rules are perpetually enforced on the same plane throughout time.

Tetris's perfection, the completion of rows, measures the player's progress in the game, just as a clock measures time's progression in infinity. Both are bound to malfunction from the stress of their respective tasks, but that's for good reason.

If the stress were to be removed, your average Joe could erect some scaffolding into heaven and usurp the divine throne when God got up to use the john. Tetris doesn't allow that. Infinity ensures that Tetris's difficulty curve gives average Joes and savants alike an equal challenge. Subtract infinity from Tetris and its difficulty scale is less than perfect.

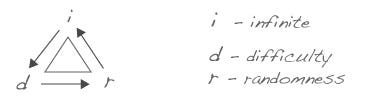

When this is considered alongside the previous conclusions on complementary elements in WarioWare and Geometry Wars, the tightly knit design of Babel type games begins to take shape. Without randomness, the role of the infinite would falter; without the infinite, the consistent difficulty scale would; without the difficulty scale, randomness. This presents a situation in which each element is crucial to the implementation of the design, and none superfluous. One could imagine the design as a gearbox or clockwork, or an ecosystem.

This so far has been about how a game upholds itself, how the elements depend on each other to sustain a design. Another curiosity lies in how these elements interact to expand beyond themselves. More complex themes emerge from these relatively straightforward concepts. From here forward, instead of withdrawing an element to assess the damage done, a positive approach to analyzing the elements of design will be introduced. This live-and-let-live perspective will account for the anomalies that arise from elements acting in accord.

The first emergent element I'd like to touch on is the element of confusion. Confusion is a secondary design element in Tetris. I say it's secondary because there is no basic design function we can point to and say "that's confusion". Still, confusion is there, just slightly harder to label, as it results from the cumulative functions of the primary elements that have already been discussed at length: randomness, consistent difficulty scale, the infinite.

Any worthwhile puzzler will provoke confusion. That's their hook. They require us to sort through a series of cognitive processes in order to reach a solution, and this state of sorting can be called confusion. In these instances, confusion simply means being perplexed.

So, when I'm playing Tetris and have an S piece in the preview window, I might be perplexed as to where to place it. Yet perplexity is a result of all sorts of things, from science exams to Sudoku, many which have nothing to do with the primary elements of the archetype. While perplexity is sometimes present, as it is in Tetris, our archetype is not its source.

It is, however, culpable for a more mischievous, even aggressive, kind of confusion. The archetype procreates disorientation, a confusion which doesn't result from sorting through cognitive processes, but from being overwhelmed by the sheer number of cognitive processes required to be sorted through at a given time.

This confusion usually accompanies the endgame of a well-played game of Tetris, when the endless rain of random pieces becomes too intense to manage, the screen half-full with unintended placements. In these moments, the player's communication with the machine breaks down. Signals cross -- does this piece rotate left or right? -- as language flickers in and out like a distant radio broadcast. Order is only restored at Game Over via simplified command: "Press Start."

"Disoriented" must have been how the Babylonians felt when they suddenly found themselves incapable of corresponding with the person next to them, and when God, according to a version of the story found in pseudepigrapha, destroyed the tower with tremendous winds. Standing in the sun, bewildered by a mystic power that had not only rent their ziggurat but their very minds, they might have reflected on the source of all language, which, according to Moses's account of history, was the all-knowing, ever-being God.

It was God who uttered the first words and thereby established the world from chaos. Soon after, he created man from dust, and man inherited language from God. So it speaks volumes to the nature of mankind when, only a few pages later, we find the descendants of that first man attempting to overtake the spiritual hierarchy. Observing this, God determined language to be the root of the problem, the very language which he had used to create the world, and in turn, man.

As such, the source material presents a situation in which man attempts to rise above himself, using the tools and materials from which he was created: language and dust. This is a defining example of pulling oneself up by one's own bootstrap. This attempt at self-empowerment parallels with our own attempts at playing Babel type games.

Games like Octopus from the Game & Watch series encourage players to will themselves to power, since they lack built-in goals, relying on the player's desire to best previous performances as the sole source of motivation. In this way, these games feed off themselves, implementing a string of user-defined goals, where the player sets a benchmark and then attempts to eclipse it.

This secondary design element arises from the instances when confusion pulls the rug out from under the feet of perfection. This includes instances such as death in Octopus, where players end up caught in the tentacles of a gargantuan God, foiled in their attempt to steal away the sacred knowledge that it guards. It's in these instances that our strides toward divinity are crushed, just as the Babylonians' were.

Yet if one were to get acquainted with the octopus, not in a superficial way, but if they really got to know it, they might cease to consider it their nemesis and even come to be in awe of it. After all, that callous, machinelike octopus embodies most of the properties we esteem in a supreme being. It's everlasting. Its ways appear chaotic, but are in fact methodical and orderly. It serves as an ideal of perfection. It's mysterious, and its mystery is shrouded in confusion.

Surely, something greater than ourselves can be constructed out of that.

I doubt I can convince anyone to worship an image of a cephalopod on a liquid crystal display (unless the "Pokemon are real" people happen to be reading), but perhaps I can garner a little praise for the Babel archetype. The Babel archetype is almost alchemic in the way it melds its components into something oft sought after and of considerable value: the definite interactive entertainment experience.

This transmutation of base materials into gold results from the arrangement of the elements in the alchemy pot, and from the relationships that the arrangement forms. It's these relationships that ultimately make games like Tetris, Geometry Wars, and WarioWare enjoyable.

To paraphrase my analysis, the three elements of endlessness, randomization as an obstacle, and a consistently increasing difficulty scale relate to one another in a couple of ways. They uphold each other in such a way that if one were removed, the rest would fall down. That is to say they function individually to form a whole.

Also, more complex design elements emerge from their relationships, including elements such as confusion, self empowerment, and of encountering something greater than ourselves. Not only do they function individually to form a whole, but they function as a whole to form something else entirely.

This brings to mind another entity that I have propagated throughout this analysis, the theist God. Theology has not only exposed God's nature, but, based on a culmination of obscure passages, accounts for the shape of God as well. For God is revered as the Trinity, and it's this conception of God as a three-in-one, as-seen-on-T.V. contraption that distinguishes the modern day God from the God of yore.

The basic idea behind the Trinity is that God is composed of three entities, all which are one, and at the same time, separate. While this proposal doesn't make much logical sense, it seems more feasible when thought of in regards to the motto E pluribus unum, or, better yet, in regards to the composition of our archetype. These religious entities function in much the same way that design elements do; individually, to support a whole, and wholly, to form an entity greater than their individuality.

It seems fitting to call the Babel elements a trinity, not a trinity of some spiritual significance, but a trinity of design. Yet, it seems difficult to derive further comparison between our trinity and the Trinity. Relating elements of the trinity to entities of the Trinity would be nigh-impossible, since so little of the Trinity's modus operandi is known.

In fact, our trinity compares more favorably to the Hindi Trimurti, in which Brahma the One who Creates would be analogous to randomization, Vishnu the One who Maintains, to infinity, and Shiva the One who Destroys, the increasing difficulty scale. However, while individual elements may not compare, the overall arrangement, the shape of the archetype, does.

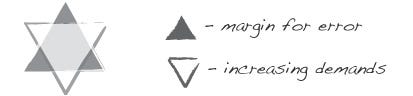

As previously postulated, each element of the trinity attaches to another in such a way that if their arrangement was charted, they would complete a triangle. Also, these games can be seen as triangular in regards to how they begin with a wide margin for error that is slowly whittled down to a point, or, to take the opposite perspective, in how their demands stack up. This can be observed if we draw something similar to a plot diagram, only modifying it to chart interaction.

It just so happens the triangle has long been the symbol for that other Trinity, the trio of aspects belonging to the theist deity. While it's tempting to cross a bridge into esoterica at this junction, speculating on the relationship of both trinities to the upper echelon of the Sefirot, that road leads outside the boundaries of my knowledge, not to mention the scope of this analysis. As thus, I'm satisfied to comment on the triangle in its more credible occurrences.

The triangle as a symbol for the Trinity turns up in all sorts of places, Kabbalah being among the least of them. The one readers are probably most familiar with is on the back of a dollar bill, where it encapsulates the all-seeing eye of God. As one might expect, the triangle is also prevalent in the art, artifacts, and architecture of churches, monasteries, and cathedrals across Europe. In fact, it's in the religious art of the Middle Ages and Renaissance that the Trinity's affinity to the triangle can best be seen.

The modern church could be considered the antithesis of the arts, so it's somewhat ironic that, when all is taken into account, the church has been a massive patron to the arts since shortly after the year of our Lord, and many, many artistic marvels can be attributed to its patronage.

In the early days of the church, anthropomorphic depictions of God were considered taboo, so the first overt images of the Trinity didn't begin appearing until around the 10th century. In these artworks, the Trinity is usually portrayed as an elderly father, a younger adult male, and a dove, and is most always arranged in a triangle, or found in a work that emphasizes the triangle, or both.

For around the past millennium or so, Christian symbology has associated the triangle with spiritual ideals, as demonstrated in paintings such as Diego Velazquez's Coronation of the Virgin, but the metaphor of the triangle is by no means exclusive to it, and likely adapted from more ancient symbology -- take the Egyptian pyramids for example.

While I'm ill-prepared to offer the reasons Egyptians built their burial chambers in the shape of giant triangles, one could safely assume it had something to do with prevailing in the afterlife, especially given all the bizarre rituals that transpired within. Then, there's the Norse valknut, of which even less is known, except that its etymology suggests a connection to slain warriors and binding spells.

Just as the symbol of the triangle is not limited to the Trinity, nor is it designated to our trinity. Tetris and games with similar elements can be likened to a triangle, even the Trinity, but that doesn't exclude games with dissimilar elements. Surely countless other types of games are bound together by this same shape. Games with paper-rock-scissors mechanics and farming games that involve planting-growing-harvesting immediately come to mind.

This implies that while the individual elements of a game may compose an archetype, the arrangement of those elements in relationship to one another comprise their form, and that is the greater good, as understanding forms can lead to rich, new experiences, while understanding elements only leads to iteration.

That's why I say there is no "truth" in games. If the elements that compose a game are indefinite, how fleeting are the avatars of these elements? Would not the Sistine Chapel be as splendid if it depicted the myths of the Greek pantheon? If instead of God the Father outstretching his finger to Adam, it revealed Zeus's conquest over his father Kronos?

Indeed, how insignificant is the dilemma of day-to-day experience when compared outside our everyday lives?

In his allegory of the cave, Plato describes a horrific scenario in which a group of people had been imprisoned in a cave since birth. These people were shackled in such a way that they could only face one direction, and in that direction was a shadow play, which was projected upon a wall of the cave by their tormenters. Being that they could only face the wall, the prisoners knew nothing of their captors, nor of the marionettes and fire used to project these images before them, nor even that they were prisoners.

They believed the images projected before them to be absolute, and were satisfied that the shadows comprised the whole of existence. It would be hard to imagine the degree of astonishment, of disbelief, experienced by one of the slaves when he was suddenly unchained from his shackles and led out of the cave into the light of day. Plato goes on to explain how the man eventually learned of life outside the cave, of the sun and light and shadow, and of how what he had thought was genuine was merely shadows cast on a wall.

The artist who understands forms is like the man who travelled outside the cave into the world. With this understanding, he can set aside the limitations of everyday life and create life anew. He has seen past his subject into the realm of forms, a realm which is perfect and infinite, but elusive, hidden from us by our own confusion.

He has seen into the realm of forms, and because of it, he can appeal to a greater truth. It makes no difference whether the artist is a street performer or game designer. The truth found in an artist's subject matter is only an interpretation of a shadow projected on a wall, but the truth of the source of that projection, that truth is not to be interpreted, but experienced.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like