At VRDC 2017, Jesse Schell discussed VR/AR innovations and insights derived from decades of teaching a class on building virtual worlds at Carnegie Mellon, showing clips from dozens of student projects.

Virtual reality and augmented reality may seem like new mediums, suddenly made viable by the emergence of the Rift and the Vive and Hololens. But Jesse Schell has watched hundreds of people build immersive VR and AR environments for the last several decades. And he has some general lessons to impart from his experience.

That was the subject of Schell's Monday GDC talk "Lessons Learned from a Thousand Virtual Worlds." In addition to being the CEO of Schell Games and the developer behind the acclaimed VR title I Expect You to Die, Schell is a longtime professor at Carnegie Mellon, where he's taught Building Virtual Worlds and Game Design, a course originated by Randy Pausch. The idea is to create small interdisciplinary teams of students--coders, artists, designers, drama geeks--and give them a couple of weeks to create a virtual world.

Schell played a clip from Pausch's famous last lecture, in which he described being surprised and amazed by what his students managed to create. Then Schell showed video clips from scores of projects he had overseen, and discussed some of the broad rules about VR/AR design that could be derived from them.

1) Worlds that create an unexpected twist are always really popular

"Some people don't wanna put surprises in VR games--they just simulate reality," notes Schell. "But it's the things that have some sort of twist that tend to do well."

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Schell illustrated this with clips from a VR game in which players can pilot a kayak down a river with a paddle. The leisurely ride is soon spiced up by rapids, falling boulders, and a waterfall that can only be avoided by grabbing an overhanging tree limb. Then the tree limb breaks... "That was made fifteen years ago by Shawn Patton, who just designed I Expect You to Die," said Schell.

He also showed off a student VR project called Hello.World that takes a very unexpected turn:

2) Get up close

"The brain has special nuclei for objects that are within arms reach, and VR is able to turn those on," says Schell. He illustrated that with clips from a game in which the player and an NPC are trapped in a tiny room, when all of a sudden a T-Rex's head bursts through a window and is snapping at you.

3) Great sound design is key

Schell illustrated how sound can add to the immersive nature of VR by showing a student clip about trying to rescue someone from a crashed subway car. The echoes in the tunnel, the screams of pain, and the metallic grinding as the player forced doors open were very evocative.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Jesse Schell shares lessons derived from a thousand student projects he saw while teaching the Building Virtual Worlds and Game Design course at Carnegie Mellon

Jesse Schell shares lessons derived from a thousand student projects he saw while teaching the Building Virtual Worlds and Game Design course at Carnegie Mellon

4) Hand presence is real

"More and more people are understanding that being able to reach into a virtual world greatly increases [the] sense of being there," says Schell. He shows several student projects that illustrate this idea. One was a sort of puzzle game that played out on a giant object like a Rubik's cube, and required players to spin and twist it to reach their goals and dodge enemies. Another was a VR version of Tetris, which Schell says was successful because it placed players up close to the falling blocks, so they had to look upwards to see what was coming and look downwards to place the blocks, using both hands to do so.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale) Student Tetris VR project

Student Tetris VR project

He also showed off a student project that superimposed live video footage of a player's hands over the game world. "It's so powerful to see real footage of your hands in the game," says Schell.

5) Proprioception matters

"If the position of a figure in the game world matches the player's real world body image, that triggers mirror neurons, you feel much more connected," notes Schell. He shows footage from a skiing game that reads the collective body position of the crowd, and whether they are standing or sitting controls speed of the onscreen skier. (And increases their groans of empathy when the skier faceplants.) He also shows a student that tasks players with shooting arrows at giant monsters from horseback--an homage to Shadow of the Colossus--that is played by strapping on an HMD and mounting a fake horse.

6) Familiarity breeds immersion

Schell notes that if you present players with an alien environment, it makes it more difficult for them to be immersed. He shows off a student project set in an elevator, which generates fright and trepidation in part because the environment is intimately familiar.

7) Avoid motion sickness

In addition to dazzling him with new and innovative uses for VR and AR, Schell says that some student projects have shown him new forms of motion sickness. "We have quite a history with that in this class," he says. "They've shown me that there are undiscovered realms of motion sickness just waiting to be discovered."

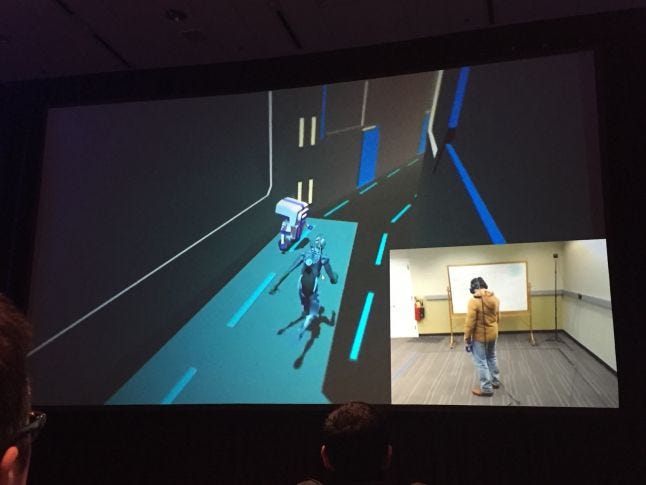

One cyberpunk-themed project kept the avatar at the center of the screen in a third-person perspective, and the player was constantly swiveling around it whenever they moved their head. "It was intensely sickening, and it was a new variety of motion sickness I've never experienced before," says Schell. "For two hours after I played it, I couldn't walk in a straight line."

This student project made Jesse Schell experience a completely new form of motion sickness

This student project made Jesse Schell experience a completely new form of motion sickness

8) Custom object interaction

Schell showed off a simple burger flipping VR game, in which the burgers all know that when they are in close proximity to a spatula, they should jump onto it. That sort of custom interaction can improve the experience of a virtual world. He also showed off a project that involved walking along a balance beam while wearing a head mounted display. In the game, you are walking along a narrow beam a hundred feet off the ground, and Schell assures the audience that the effect of playing the game while walking on a real beam is gripping.

9) Eating in VR/AR is fun

Schell notes that you can guzzle champagne and chomp on sandwiches in I Expect You To Die, and says that he learned from student projects that eating in virtual worlds can be fun. He shows off a student game in which the player is a giant, helping your tiny friends defeat their tiny foes by scooping up the foes in a huge spoon and gobbling them up.

Other clips showed how student projects successfully employed live video clips, gaze tracking, live singing, and social interactions as simple as high-fiving. (This was something that the players themselves figured out how to do in a game that simply allowed players to clap their hands.) All of these elements, Schell insists, have a role to play in the future of VR and AR.

Read more about:

event gdcAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like