Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Interview: The Best Game History Book You’ll Ever Read?

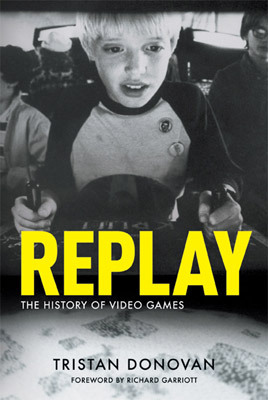

UK journalist Tristan Donovan did what most considered impossible: write an adult, balanced account of gaming from room-sized mainframes to the PlayStation 3. In this exclusive interview, Tristan explains what makes REPLAY so special.

[UK journalist Tristan Donovan did what most considered impossible: write an adult, balanced account of gaming from room-sized mainframes to the PlayStation 3. In this interview, Tristan explains what makes REPLAY so special.]

Where did the idea for another “history of video games” come from?

It started when I read Stephen Kent’s The Ultimate History of Video Games. It was an interesting read, but it bothered me in some ways.

For a start it ignored Europe. It was as if the whole continent had sunk into the sea. Coming from the UK, which has a long history of producing significant games from MUD through to Grand Theft Auto, it seemed a major oversight. I also felt there wasn’t much about Japan’s domestic gaming culture either. What happened in the US is extremely important but only tells part of the story.

Kent’s book was also a history of coin-op and console games, so games on computers and other platforms rarely got a look in. That meant important genres such as text adventures and role-playing games were left out.

And although it’s in line with how we tend to treat game history at the moment, I disagreed with its perspective on game history - where games develop almost as a by- product of new generations of hardware. It’s what I call a ‘kings and queens’ approach to history. First came Atari, then Nintendo, then Sony, etc.

Now that’s a valid approach, one of many perspectives you can take on game history. After all, history isn’t physics and so interpretation is a big part of it. But to me hardware is something that either aids or limits developers from achieving their creative vision. It’s the creativity of developers not the hardware engineering that makes games. The architecture of the PlayStation 3 did not ensure that a game like Heavy Rain would be made, for example. All it did was make it possible. It took the ideas and creativity of David Cage and his team to make it.

So I felt there was another history of games to be written. One that covered the world, one that looked at all game platforms and, most importantly of all, one that framed game history in the context of broad trends in game design rather than through the prism of successive generations of console hardware.

And at some point, I don’t know when - there wasn’t a light bulb moment, I decided I should write it. I felt I was in a decent enough position to do it, I’d been a journalist for 10 years, I wanted to write something more in-depth and I had dabbled in games journalism, writing for magazines such as Edge and Game Developer.

I guess that after thinking about it, I decided that rather than waiting for someone to write the game history book I wanted to read, I should get off my backside and do it myself.

Did you go over other game history books before starting work on your own?

Obviously Kent’s book was the starting point, but after deciding to write the book I began by gathering up as much info as I could. I went through hundreds of old magazines, newspapers, websites, journals, games, game manuals, TV shows and - of course - other books. I read dozens of books about games and, with one or two exceptions, all the game history books available in English. And that was how it started, months of reading and note taking. I think I ended up with something like 2,000-plus A4 pages filled with notes.

I noticed that a lot of the material is fresh. Did you interview game personalities specifically for the book?

I interviewed around 145 people from across the world specifically for the book. I felt it was important to do that for three reasons.

First, I wanted to fact check. After reading a lot about games I realised some accounts of what happened simply don’t add up or are contradicted elsewhere, so I wanted to investigate those more and double check the accuracy of what I found.

Second, I wanted to have the voices of the people who made game history in the book. Most history books come out long after the people involved in events have passed away, but most of the people who were there are the beginning of video games are still around. So I would have been nuts not to try and get their eye witness accounts. It was also one of the most enjoyable bits about doing the book, getting to speak to all these people who built the medium and, in many cases, created the games of my childhood. I’m eternally grateful for the time they spent helping me since these weren’t short interviews, I think on average they lasted about hour.

Finally I needed to speak to people because I was trying to break away from the standard console generation narrative of game history. To do that I had come up with a bunch of hypotheses, based on my research, to explain what happened and why. But I needed to test these out on the people who were there to see if my hypotheses matched reality. Some did, some didn’t, but only by speaking to the people who were there could I be sure.

I also noticed that you added some choice quotes from what seem to be old newspaper articles. Did you use a service like LexisNexis?

I didn’t use LexisNexis, although in retrospect I probably should have. Don’t know why I didn’t. A lot of the newspaper articles I found, I tracked down after seeing them referenced elsewhere, but probably the single most useful tool was Google’s News Timeline, which has searchable scans of hundreds of old newspapers and magazines. It’s clunky and slow but very useful if you’re patient. It was great to find those old newspaper articles to get a sense of how people reacted to games, particularly early on when people were experiencing games for the first time. People can try to remember, but really those articles where journalists explain things like Pong to an audience that probably hasn’t seen a video game provide some interesting insights. For example video games did a lot to change public attitudes to arcades in ’70s, which were seen as seedy places where your children would get lured into drugs.

Some reviewers on Amazon criticize the cover (although I like it myself). What was the intention of choosing a B&W, nostalgia-infused picture for the cover? Did you choose it yourself?

I suggested it and the cover designers liked it too. I guess whether you like it or not is a matter of personal taste, but I didn’t want to go down the obvious route and just stick a Space Invader on the cover or have some crazy, primary color mess that looks like a game magazine.

The idea behind the cover and all the images in the book was to use photos that captured a sense of the times. I didn’t think screenshots of games would add much, people can find game screens or videos on Google within seconds. I felt photos that summed up the era were more distinctive and more unfamiliar to people. And I think we’ve got some great photos in there as a result, photos that few people have seen before such as Bill Pitts and Hugh Tuck building the first coin-op game.

It also connects to the philosophy that partly inspired the book: that games are about people - developers and players - and are interesting first and foremost because of how they make people feel.

I really like the cover photo, it was an interesting and clever photo that captured something about being a wide-eyed kid absorbed in a game. A lot of people have said it reminds them of their youth. Originally it was going to be used inside the book, but it didn’t really fit any chapter. It was only when we started discussing the cover that we hit on the idea of using it on the front.

The cover of any book is ultimately there to make a book stand out and to attract attention, so it works on that level whether it’s to your taste or not. I know some people would like a more ‘gamey’ cover, but it’s not a coffee table book and I think those who will want to read it will be intelligent enough not to need some video game character lunging out at them on the front. I don’t think it needs to look like some kids book just because it’s about games. Personally, I feel those sort of covers are a bit patronising. Why should every video game book need to look like it escaped from the children’s section of the bookstore? It could be a bad move commercially, I don’t know, but in creative terms I think it was the right choice.

What was your history of video games? How did you start, what are your favorite consoles (or PCs) of all-time and why?

Well my starting point was playing Space Invaders in an arcade. I don’t remember where it was, but I distinctly recall having to stand on tip-toes to reach the controls, so I must have been quite young.

But my interest really started when my parents got me a TI-99/4a computer in 1982, 1983. Texas Instruments stopped making it shortly after we got it, so I ended up with a computer with three games, and the only way to get other games was to write them myself in BASIC (they were rubbish in case you’re wondering).

I was stuck with it until about 1990 when I got an Amiga. So I spent the 1980s looking enviously at my friends’ Commodore 64s, ZX Spectrums and BBC Micros. My best friend at the time had a ZX Spectrum and I used to play it all the time. I even started buying game magazines just to read about games I couldn’t buy. Looking back, I think not being able to get any new games really got me into them even more because the opportunity to play anything new or decent was so limited they seemed more desirable. I guess the road to Replay began there.

After the Amiga, I moved over to PCs around 1994. I didn’t own a console until 2001 when I got a PlayStation 2. Since then I’ve been writing about games on and off, so I’ve had to get almost every system that’s come out in the past 10 years.

Favorite system of all time? If pushed I’d opt for the Amiga because many of the games still play well today and I’ve got fond memories about playing on it. But to be honest, I’m platform agnostic. It’s the games that matter to me - the software not the hardware. Although I do really like the PlayStation’s controllers.

Is the book going to be published in the US? How about a 2nd edition?

The book is out in the US both as a paperback and an ebook (Kindle and iPad at the moment, others coming very soon). It’s mainly available online through Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Books-a-Million, etc. The publisher, Yellow Ant, is small and doesn’t have the reach to get it into book stores in a big way - even assuming there’s an appropriate section in the store. Certainly in the UK books about games don’t really fit under any section. But I don’t think that’s too much of an issue, I think most game players won’t have a problem buying it online.

It’s almost certain there will be a second edition, barring unforeseen events, but not for a few years so it can be a proper update.

---

REPLAY is beyond great. It’s the best history of video games I ever read. You can buy a copy at Amazon.

A Kindle Edition is also available.

You can follow Tristan Donovan on Twitter at http://twitter.com/tristandonovan

You can follow me on Twitter at http://twitter.com/AtmanRising

(originally posted at Stray Pixels, a place for tech, Android, games, PR and everything else)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like