Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Ico: A Balance Between Minimalism and Practicality

A breakdown of Team Ico's successful approach to compromising between their artistic vision & sensible design.

Originally posted on http://eventnode.tumblr.com

“The simplest things are often the truest.” -Richard Bach

I like Ico. I really like Ico. It was the first time I ever experienced minimalism in a way that was meaningful for me. I can point to this game as the starting point for what has really shaped my taste in games and storytelling in general. Ueda’s now well known philosophy of ‘design by subtraction’ has influenced a lot of games and ideas of game presentation since. However, a lesson I think a lot of others don’t talk about is just how practical the game is. Team Ico’s games have shown that they are willing to make concessions to immersion for a better experience and not simply live or die by the ideas of maintaining a pure artistic vision, as some might idealistically think.

What You Don’t Say

What exactly is Minimalism? It’s used not just in games, but visual art, music, literature, and design. All of these are very different in terms of their creation. But at it’s core, Minimalism is about parrying down elements used. In the case of Ico, it seems to have drove most decision making when creating content. There is no HUD, really unusual for the time (Altho not the first. See games like Another World or Alone In The Dark.), the music is used sparingly, only when there is a dramatic purpose for it. Otherwise the game’s audio is all about ambient noises. Very minimal dialogue is used (While this is in tone, there’s also practical reasons why, which I’ll get to later.). Finally, the controls & gameplay are limited in scope, with only a few moves Ico has and a handful of objects he can manipulate to progress in the game.

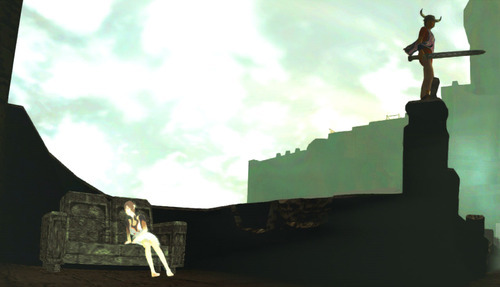

The story itself is very bare, with the exception of the beginning and ending cutscenes, and only less than a handful of shorter ones to move plot points along. You aren’t given much info about who Ico, the horned boy protagonist, other than the presumed assumptions about him being banished from society and forced to be in the castle . And even less is known about Yorda, the girl you find in a cage and the woman who locked her up isn’t pleased you let her out.

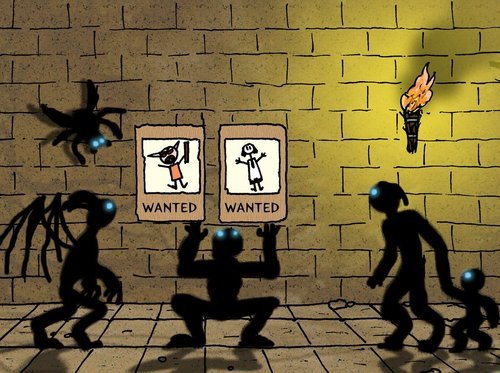

But the best of Ico’s storytelling is in what it doesn’t directly tell you, but leaves it up to you to spot and interpret. Such as the shadow enemies having horns. Are they possibly other horned people who were sacrificed? As well as the further you go in the game, their designs become more human like, and the horn design comes more into focus. Raising the point of their evil state and intent coming into question. Particularly when the game begins to contextual that the shadow enemies will only attack you and never harm Yorda. All of this information coming from the the character design and environment, never through a cutscene or dialogue. It complicates and gives perspective to the previously simplistic narrative being presented. Of course this is just my own take on it.

When to say “Oh alright I guess.”

Any creative individual, at some moment in the process, has wanted to make the purest form of an idea, without influence or considering how it would effect other aspects of the piece they’re working on. Or maybe you’ve wanted to expand on themes in a project you’'re working on whether that’s through the art or game direction. But most of the time, you have to make compromises in these areas, especially if you are trying to make something that might go against the grain. Whether it’s being really smart in their overall vision, or just lucky, Team Ico has done this quite successfully in their games.

Things like adding a hud or a grip meter in Shadow of the Colossus was a compromise they had to make at the time. While it could break the immersion for some, it was necessary in the end to have something conventional that the player can get feedback for. It also could have drastically changed the actual gameplay itself. Sometimes people get hung up on the desire to “reinvite the wheel”. While that can be the right mindset, you also have to realize that using tried and true designs can be a good fallback. It just comes down to finding the right fit.

In Ico, the most clear sign of this was in the final part. For a game that was very much going against a lot of conventions, the climax ended in a very tradtional boss fight. But it still presented an engaging puzzle more so than relying on the use of combat.

Speaking of the combat…probably Ico’s weakest point, but one I could understand being needed. Without it, there would have been only one interaction set involving Yorda. Watching someone play Ico you can see there is a an occasional visceral emotional reaction when she is being picked up by an enemy, dragged down a hole and needing to pull her out of. It has the potential to make you feel like you want to physically grab her yourself and yell “I’m coming!”

But dialogue isn’t something you’ll hear a lot of in game, or at least you can recognize as both characters speak separate made up languages. This, plays out nicely for both artistic and practical reasons. It instills in the player the concept that neither characters can communicate thoroughly, therefore giving a logical reason for there not to be a lot of dialogue and questioning it. It also gives plenty of negative space for the player to develop their own interpretations of the characters individually and their relationship as a whole.

The final cutscene is another example the two sides compromising that ends up being used very effectively. Ico is physically knocked out, and being your vessel through the world, you lose control and influence over the situation. You+ are only given control back once Ico wakes up on a beach, having been saved by a shadowy Yorda putting you in a boat while the castle collapses.

This scene in particular, reinforces an important question to making a game like this. “What do you want the player to feel?”. Alfred Hitchcock used to ask his writers when he worked on a film this question. The context of the story, what the characters are doing, can come second in a lot of cases, as long as you put the focus on what the the audience or players are feeling moment to moment.

In games, you can expand on this and create less controlled scenarios, but allow for more anecdotal and personal situations that each person can take away with them after they are done playing.. In Ico, I remember having a moment after a intense fight with some shadows where Yorda almost was taken a few times. Right after I picked her up, we started walking down some stairs, and she immediately tripped and fell on the first step. It made me think “well she just had a rough go at it a minute ago.”, But at the heart of it was more complex emotions having to do with me comprehending what she’s had to go through and how weak in comparison both her and Ico were individually.. It made me feel empathy for both of them.

Ultimately, the overall concept I take from Ico is, finding a balance between the pure idea and whatever other elements that can be added or subtracted to create a more focus and/or meaningful experience.

Takeaway

What makes Ico special, can be added on in retrospect with what Team Ico did with their next game. Shadow of the Colossus is built on the back of Ico’s principles and excels on expanding them. Shadow is seen as a progressive step forward, largely because of it’s improved and focused gameplay. But without Ico as the foundation to build from, that game wouldn’t exist. It’s a game that can still teach the importance of building up an idea, tearing it down and replacing parts of it.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like