In this thorough Deep Dive, Nauticrawl dev Andrea Interguglielmi walks through his process of designing this atmospheric puzzle game to evoke feelings of genuine mystery and wonder.

The Gamasutra Deep Dives are an ongoing series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including building an adaptive tech tree in Dawn of Man, achieving seamless branching in Watch Dogs 2’s Invasion of Privacy missions, and creating the intricate level design of Dishonored 2's Clockwork Mansion.

Who: Game developer Andrea Interguglielmi

Hello! My name is Andrea Interguglielmi and I’m the developer/artist behind the mysteriously intricate game, Nauticrawl.

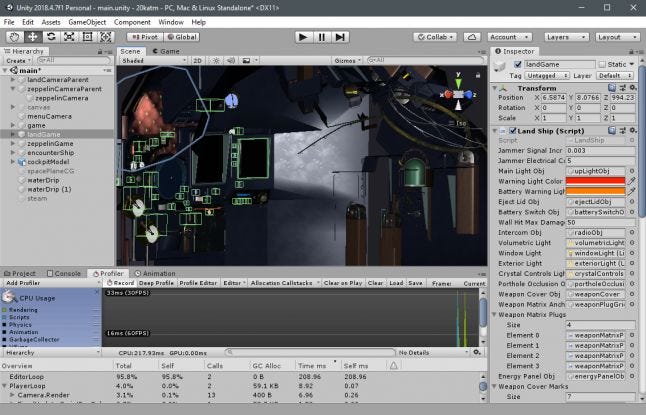

Before finding myself back in full time indie game development, I took a long detour through the movie industry, working as a VFX tools dev and technical director. Some years before that, I worked at Lionhead Studios. However, the start of my journey in this industry dates further back with designing and pixelating adventure games on the Game Boy Color.

In this deep dive, I will go over how blending and layering different gameplay elements in a rather non-conventional way contributed to shaping the unique experience that is Nauticrawl. I will list some of the ingredients that are part of this weird recipe, how they interact with one another in a precarious balance, and I’ll try and sum it all up as an abstract formula that *maybe* could even be replicated to make different games.

What: Evoking mystery and wonder through puzzle game design

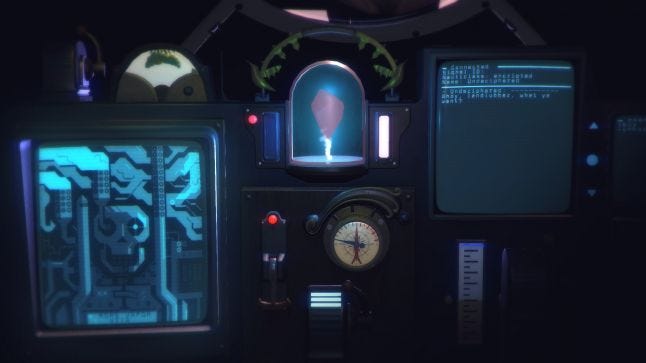

Nauticrawl is an atmospheric game with a very simple premise: you’re attempting a desperate escape, and stealing a mysterious machine is your only way out. Flavored with just a bit of lore, this is literally the only thing the game will explicitly narrate before you’re thrown inside a cockpit full of buttons, levers, and gauges.

The game won’t bother with details about why you’re trying to escape, or where you’re coming from, not even where you’re supposed to go. Admittedly, this is the ideal premise for an escape room type of game - nothing much in the way of curiosity and the urge to fiddle with everything that can be touched.

Nauticrawl could have been just that: a game about pressing all the buttons and figuring each puzzle in a chain of progressively unlocked and increasingly difficult stages. It probably would have made for a cool spin-off of The Room, but my desire with this game was to experiment further.

Unblocking, fully immersive, very unsettling puzzles

Nauticrawl does indeed start as an escape room, but as soon as the player solves the first puzzle, which is about turning on the machine, something rather unconventional happens. The game does not stop to tell the player whether he has accomplished something or not.

To be more precise, the result of figuring out how to turn on the machine will actually feel very rewarding, as the whole cockpit will come to life all of a sudden. But there won’t be any pause, cutscene, high-score result or anything that makes it clear that the player is now moving to puzzle number two.

The result of switching on the machine is indeed that the machine is now running, and the fact that nothing else happens to break this immersive moment can be rather unsettling, but hopefully just as intriguing.

Turning tutorials into puzzling mystery

The idea of not stopping the game when a puzzle is solved is not a stylistic choice here, nor a deliberate artistic stance on unconventional game design practices. Rather, it's the emerging restriction of another gameplay mechanic that is progressively surfacing. What is happening is that as the player understands this ancient and mysterious machine, new gameplay elements are about to emerge.

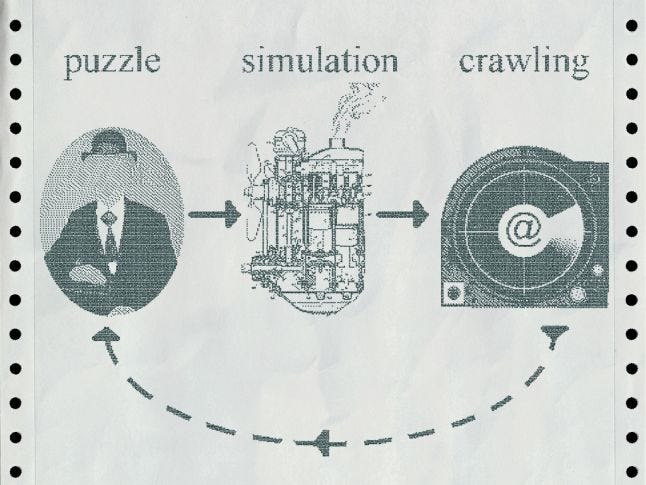

This creates an entanglement between very distinct mechanics that is not immediately obvious, but it will become more apparent once the player has figured out how to turn on the engine and move the machine around. What played as an escape room puzzle at the beginning, is now turning into a cockpit simulation game.

The ability of the player to perform well as a pilot will now be determined by the amount of knowledge obtained from the escape-room puzzles. In fact, the puzzles are effectively working as a tutorial to teach how to pilot the machine, which as it turns out, is part of the real core loop of the game. Yes, only part of it, as there’s actually more.

Nauticrawl is a big pot in which I’ve thrown some of my most beloved gameplay elements that I longed for to see combined into a single experience. The escape room puzzles work well to explain a complex vehicle interface without any tutorial, but these two elements combined don’t form the whole picture yet.

Once the game reveals itself as a cockpit simulation game, there comes the moment where the player will experience what it’s really like to pilot this house-sized machine. Will it be like flying an airplane, hovering in a gravity defying space-ship, or diving a submarine underwater? That’d be a consistent choice to go along with the cockpit sim gameplay the player just got accustomed to, but, by now you probably know that’s not how this game rolls. I mean, crawls.

Crawling through gameplay constraints

Making the machine move is a crucial moment that comes right after having asked for a lot of trial and error from the player. By now, the game has managed to build up a convincing suspension of disbelief, having allowed the player to do anything while feeling unblocked. Indeed, the game is about to shift once again into another type of gameplay, this time about exploring a planet using the newly acquired knowledge of how to pilot this machine.

A central monitor shows a log of what happens inside and outside of the vehicle, while a radar shows a top-down view of the surroundings with fog-of-war to keep track of the explored area. One pull of the designated lever and the machine will make a big metallic stomping sound, while the radar will show the map moving and the mug on the object-holder will start shaking to further amplify the illusion of motion.

But here comes yet another surprise: it won’t feel like driving a car or flying an airplane at all. There’s no inertia and no need to pull the break. The machine will crawl forward just as much ground as the lever to inject fuel and pressure have allowed it, and then everything will become still again. At this point, the battery indicator, as well as all the various gauges for pressure and fuel will be updated to display the outcome of the user’s interaction.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Whether the player realizes this yet or not, they have just executed a turn. The whole machine is a big mechanical dungeon crawler scattered around a simulated cockpit and there’s a whole world out there to be explored, one move at a time.

It’s a world that can’t be seen directly. By now, the story of the game has revealed more details about the impossibly heavy atmospheric pressure on this planet, and that’s also why you’re always stuck inside this machine with no windows. Luckily there’s a button to have the on-board computer render a textual description of your surroundings; it’s the only way to know what’s outside. Finally, your surroundings can start to play a more important role in the game. Even though they can’t be seen directly, the radar will show icons of what can be interacted with and what might be a threat. There will be terminal-stations to be hacked and creatures that will make some creepy sounds around you.

The environment and the player’s ability to explore will finally start to feel like a more traditional old-school roguelike, with environment puzzles to be solved, enemies to watch out for, and strategic choices to overcome obstacles.

But none of the previous gameplay elements are totally ever left behind for good. At this stage, the machine is still not entirely solved as a puzzle. The game is juggling between escape room, cockpit simulation, dungeon crawling, and roguelike cyclic narrative. Each of these game mechanics is enforcing constraints on one another, making this a very hard game to iterate on and balance towards an exact audience. In fact, you will rarely see this title addressed with a specific genre in any of the official communication channels. We prefer to refer to it as more of a unique experience in its own little niche.

Results

Nauticrawl ended up mixing a lot of ingredients from its rather non-conventional recipe. At some point, the machine will shape-shift into something completely new, and the whole cycle of puzzle to simulated interface to exploration will repeat itself another couple of times in completely new forms.

Designing around such vast but also limiting rules has been one edgy, bumpy yet exciting ride. Nauticrawl pushes players into mysterious and uncharted territories of experimental gameplay and narrative design, but the reception has been incredibly heartwarming and showed there is plenty of room in this niche for more genre-defying content.

I’m aware that most likely this is not a scheme that can be adapted to many different games, but in its most abstract form, it might fall into a formula that could see more entries with time. Write this recipe down if you will, it can make for some good experimental food for thought:

Start with a simple premise to justify why the player is venturing into the game blindfolded.

Throw the player in front of a mysterious puzzle.

Make the puzzle an actual user interface to another core gameplay loop that is yet to be revealed.

Slowly unravel the core gameplay loop, factoring in what the player has learned through the puzzle stage.

DO NOT add any tutorial, no matter how tempting. It’d ruin the taste.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like