From Indie to AAA: Notes from a Game Writer

The path to becoming a video game writer is tough -- and different for everyone. But in case it helps, here's how I got started. My video game career began after a hilariously bad birthday.

Being a professional video game writer is one of the best jobs around. Period. I’d love to see the look on my six-year-old self’s face if I told him I’d be writing video games one day. But here’s the real talk. The path to becoming a video game writer is tough -- and different for everyone. But in case it helps, here's how I got started. My video game career began after a hilariously bad birthday.

The Bad Birthday Pivot

My girlfriend and I had recently come back to the States from Japan after the Tsunami of 2011. I’d left a soon-to-be amazing teaching job in Tokyo, the type of gig an aspiring novelist dreams of: short hours, great pay, plenty of time to write on the side. But with my family’s concerns over the Fukushima situation, we came home instead (blowing much of my savings in the process) to Florida to crash with my parents. The plan was to recoup a bit and then figure out next steps. Then my girlfriend and I broke up, a week before my birthday. So, to review: Recent break-up. Unemployed. No savings. Living with parents.

Chrono Trigger

On the morning of my birthday, I dug through my closet, found our Super Nintendo, and fired up Chrono Trigger. Alongside the novels I’d read that shaped the type of novelist I wanted to be, video games had also impacted my imagination and sense of story, games like Final Fantasy IVand VI, and of course, Chrono Trigger.

While I was playing, my mind drifted to my writing career, and how I wanted to be a working writer -- that is, I wanted to pay the bills with my writing, rather than my writing being a “when I’ve got time” situation. Most writers go for TV and movies, incredibly competitive but potentially lucrative careers. But I wasn’t sure I wanted to move to Los Angeles.

I asked myself what I liked about storytelling in videogames. The answer was that I felt like I was part of the story, instead of an observer in someone else’s story. One writing career lesson I didn’t learn soon enough is that sometimes you have to pivot when one avenue isn’t working out, so, I said to myself, I should try to make it as a video game writer.

Then the inevitable question followed... so how do you become a video game writer?

My First Strange Gig

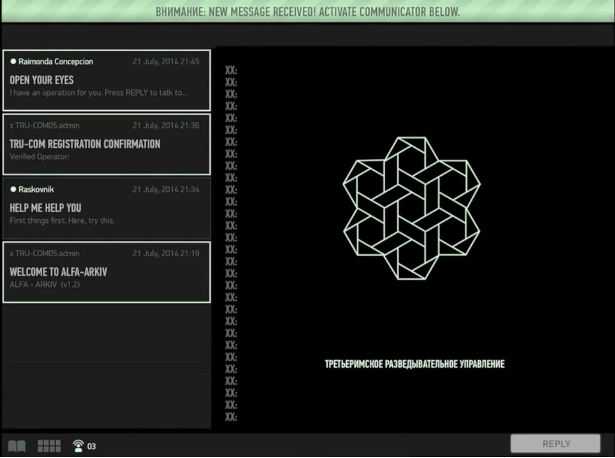

I scoured game studio websites for an entire year, but I didn’t see many open game writer jobs available. Then, one day my brother told me about a guy he’d recently met looking for a writer. I sent a few sample scripts, which the team liked, and I was hired. It was a strange, ambitious, iPad game called Alfa-Arkiv.

Alfa-Arkiv

For this first gig, I wrote a series of fictional emails hidden within the app. You’d consider it a secondary or even tertiary story -- imagine the types of emails you read while playing Deus Ex. The emails explored the backstories of several main characters. I suspected that most players wouldn’t read this content, but in video game writing you sort of have to have that mentality. Some people gobble up story at every opportunity, and others skip in-game text like the plague.

The value of starting your career by working on a small team is that you get to see the entire game develop right around you, day by day. You collaborate with people from every discipline. Even the discussions on how to market the game were new and exciting to me. Although Alfa-Arkiv wasn’t financially successful, it did manage to get recognition from CNETas one of the best mobile game of 2014, and more importantly, I learned a lot and cut my teeth with professional and very talented developers in the process. As the game was nearing completion, I started to look for other gigs, but again, there weren’t many game writer jobs being advertised.

If you don’t see a game writing job, try to find indie developers working on a game you’d like to write. That’s what I did, at least.

Kickstarting a Game Writing Career

I tracked tons of indie projects before eventually reaching out to a Mexican developer making a retro Zelda II throwback called Elliot Quest. Basically, I asked him if he needed help writing the story, and ended up helping him run a small but successful Kickstarter. In the meantime, I also jumped on a few other indie games. Of them, Elliot Quest was the only one to get a publisher and came out on most modern game platforms, including most recently the Nintendo Switch.

Elliot Quest

While I was working on Elliot Quest, I started taking notes on the games I was playing, analyzing story, character development, pacing, and what narrative tools the writers had at their disposal. I also began reading game design books like: Theory of Fun and The Art of Game Design.

As Elliot Quest’s development was wrapping up, I finally found a few video game writing jobs and applied to all of them. I received plenty of rejections, most of the time in the form of never hearing anything back. This is part of the entertainment industry, and certainly videogames. Competition is stiff. Getting noticed is a combination of hard work, who you know, and luck. For a select few studios I got a writing test, and of those I interviewed with one or two companies. But no job offers.

I didn’t know many people in the game industry, other than a handful of indie developers. I had two indie game credits to my name. If I had to guess why my materials got noticed, it’d be that I wrote speculative scripts based on mainstream, popular games like Telltale’s The Walking Dead and Mass Effect. Although I’ve never written fan fiction, a spec script can be a powerful tool to demonstrate to potential employers that you can write in a particular voice or genre:

Never underestimate the power of a spec script.

Multitasking My Way to AAA

Armed with spec scripts, I got my first mid-sized studio job, a six-month contract working for Trendy Entertainment. My employment started right after some upheaval at the studio, after which I joined a pre-production team for Dungeon Defenders 2. I wrote a lot of lore and world-building documents, as well as character bios.

My Walking Dead Game

In 2013 I saw that the University of Texas at Austin was starting a video game fellowship, the Denius-Sams Gaming Academy: Free tuition and a living stipend, and directed by Warren Spector. There were only twenty spots, and I figured that a video game writer didn’t have a chance in hell of getting in. But I did.

Although I never took a coding class in college, I knew that having a more diverse skillset would both make me more attractive to potential employers as well as give me a better insight into how games are made – which would translate into my ability to write better video game stories. I took all the basic courses in code academy, and also began to (slowly) learn a game engine, Unity. Later, I’d use Unity to build interactive games (Telltale-Lite) but more interactive than, say, a Twine game.

Anyhow, I also learned basic level design in Unity and completed as many tutorials as I could. Armed with my spec scripts, I applied to the Denius-Sams Gaming Academy and, to my surprise, got an interview. When I was speaking to Warren Spector, the inevitable question came up. What would I do if the game we decided to make didn’t need a story? Due to my work in Unity, I was able to say that I could jump onto level design or potentially even audio (I play guitar and piano, and have sub-par editing skills). I got in.

The Denius-Sams Gaming Academy is no more, and I killed it. Kidding. Unfortunately, the program only lasted two years, and I was in the first of two classes. Really, that the program isn’t around is a shame, because in a short nine months, so much video game wisdom was crammed in my head, not just by the program’s faculty (Warren Spector, Joshua Howard, and David Cohen) but also a myriad of veteran game developers who came to speak: Richard Garriot, David Bettner, Max Hoberman, and a host of other veteran developers

Nearing the end of the fellowship, the Denius-Sams Gaming Academy hosted a job fair, and Gearbox was one of the participating studios. Write for Gearbox, the studio who made Borderlands? Yeah, I’m in.

The Road to Gearbox

By now, I had an armada of materials, indie game credits, as well as my spec scripts, which I’d turned into short interactive games using Unity and a plug-in called Fungus. As luck would have it, Gearbox was looking for a writer -- I say luck because posted AAA writing jobs are incredibly rare, amazingly competitive, and you should apply anyway. I landed a writing test, then a phone interview, then an on-site interview, and finally a job offer.

Gearbox

For most, becoming a game writer is a long, twisted path filled with tons of rejection (unless you catch a break) in which you’ll spend years working for just the opportunity to prove your writing chops. The honest truth is that there are a million factors that can ultimately determine whether you get that job or not. Who you know. The weather. So, my best advice is to:

Make your own games.

Reach out to indie studios.

Be fearless. Embrace rejection.

In the end, I got my current job at Gearbox after a ton of hard work, a lot of rejection, and some luck. That said, everyone’s path to game writing is different. But there’s an upside. Video game writers are part of a small, welcoming community. So, on your path to becoming a game writer, don’t be afraid to ask for advice along the way.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like