Finding mono no aware in American video games

An examination of American game narrative design through the lens of the Japanese aesthetic, mono no aware

Everything ends. Games, relationships, happy moments and life, the end is nigh for everything.

For some, this idea is terrifying enough to cause existential crises, mental paralysis and nights filled with weeping about the inevitable (an observation made through personal experience). For others, ends are simply what they are and accepted as a part of life.

In Japan, there is mono no aware (), an aesthetic that roughly translates in English to “the pathos of things”, but as Kakuzo Okakura once wrote, “Translation is always a treason, and … can at its best only be the reverse side of a brocade--all the threads are there, but not the subtlety of the color or design.”

From an American understanding, the complex aesthetic concept is tied to emotion--which can include love, joy, sadness and pain--and points to a thing’s impermanence and, more specifically, the idea of appreciating that thing before it is gone. In other words, appreciate the moments one experiences with things, like pets or cherry blossoms or people, in that moment, not in the future thinking about the past. Appreciate the fleeting, transient nature of these moments as they happen instead of looking back in hindsight. Mono no aware is recognizing the privilege we have to experience something before it is gone and the gentle sadness tied to acknowledging that thing will eventually disappear.

In Japan, it is culturally understood and accepted that things will come to an end and, therefore, endings, while impactful and unexpected, are often presented in narratives as anticlimactic, leaving foreign outsiders feeling an emotional void and asking, “That’s it? Now we just move on?” This is not without reason.

“Instead of causing some kind of nihilistic desperation, being aware of the fundamental transitory nature of existence is, for the Japanese, a call to vital activity in the present moment,” according to Faena Aleph, a digital magazine reporting on the cultural aesthetic.

Popular Japanese games series like Final Fantasy, Fire Emblem, Metal Gear and Dark Souls each feature mono no aware in their own way, but follow a similar idea that if something or someone did not die, “things would lose their power to move us” (Faena Aleph). In these games, deaths, like Aeris’s (

Popular Japanese games series like Final Fantasy, Fire Emblem, Metal Gear and Dark Souls each feature mono no aware in their own way, but follow a similar idea that if something or someone did not die, “things would lose their power to move us” (Faena Aleph). In these games, deaths, like Aeris’s () in Final Fantasy VII, are still moments filled with sadness, but also compel the player to keep going, to keep progressing instead of stopping and wallowing in loss.

By comparison, many American-made video games teach players that they are “immortal” and welcome to use as many lives as wanted or needed to see their heroic story through to the end, whatever that may be. This experience is best seen in games like Grand Theft Auto, Call of Duty, Skyrim and Borderlands. The player may die, but they immediately respawn and can return to the action they were just expelled from.

However, there have been several American-made games that include moments exemplary of mono no aware, and remind the player that the things they’re experiencing are a privilege, but not guaranteed to last.

This paper will attempt to critically analyze the presence of mono no aware in Bioshock, Gone Home, and The Last of Us from the perspective of an American gamer. It will unapologetically feature spoilers from each of these games and personal playthrough experiences. In turn, this article will hopefully show the varying presence of the Japanese aesthetic in American games and the significance of implementing the aesthetical concept into video game narratives.

Approaching mono no aware from an American perspective

Before analyzing American video games through a Japanese aesthetic lens, I feel it is important to acknowledge the cultural differences between Japanese and American concepts, specifically in their approaches to emotion. Needless to say, there’s a lot to be said.

According to the study “Development of Emotion Regulation in Cultural Context”:

“In Japan, ‘interpersonally engaged’ behavior and related emotions (e.g., empathy and shame) are experienced as relatively more positive; in the US ‘interpersonally disengaged’ behavior and emotions (e.g., pride and anger) are experienced as authentic and relatively more positive. … Not surprisingly, shame is more emphasized and is more accepted by Asians than by Westerners.

In contrast to empathy and shame, socially disengaging emotions such as pride and anger reflect and reinforce the individual’s sense of autonomy and desire for self-assertion, which is consistent with the Western focus on the need to protect self’s freedom, individual rights, and opportunities.”

The study continues to further dive into the differences between Western and non-Western cultures, including noting that Western cultures tend to be self-maximizing, foster self-esteem and strive for positive emotions to build up pride and self-reliance. Meanwhile, Asian cultures tend to be group-maximizing, foster face and accept negative emotions while emotions are typically encouraged to be suppressed so not to disrupt the harmony of the group (page 108).

In terms of mono no aware, Japanese citizens accept that impermanence should propel people to keep moving forward even if there is pain and sadness tied to the transient moments. In the United States, where the aesthetical concept is less known, these moments are painful and Americans tend to react in kind.

There is little to no research available that discusses why Americans respond negatively to sad or distressing moments. One might speculate that, based on the above research, these moments are subconsciously seen as an attack on the self in some way. However, this is uncertain.

What is certain is that, even in the virtual world, Americans do not always handle loss of things or people very well.

The emotional shock of BioShock

Released in August 2007, BioShock submerged players into the darkest depths of the sea and dropped them on the doorstep to Rapture, a twisted city filled with artists, innovators and opportunists. In the game, the player assumes the role of Jack, a survivor of an airplane crash that coincidentally happened to be right on top of the Rapture lighthouse, the gateway down to the city itself.

Like in many video games, players can return to life in BioShock by using Vita Chambers, the game’s equivalent to a full-recovery health potion. In this way, players are still immortal, able to regenerate themselves as many times as they wish to keep moving on in the story. Obviously, the player is not following the mono no aware aesthetic.

Like in many video games, players can return to life in BioShock by using Vita Chambers, the game’s equivalent to a full-recovery health potion. In this way, players are still immortal, able to regenerate themselves as many times as they wish to keep moving on in the story. Obviously, the player is not following the mono no aware aesthetic.

No. Instead, trust and truth are the impermanent within BioShock.

Prior to playing the game, many, myself included, had heard the news that BioShock features multiple endings. So when starting to actually play, one would think that the player should start paying attention to the details that may or may not shift the game’s final outcome.

If the player embraces mono no aware as soon as the game begins, they would ideally start appreciating the moments they’re experiencing, taking observational mental notes as they navigate their way into and through Rapture. I was not one of those players. Instead, I was too busy readying myself for what was about to come next: splicers, genetic enhancements, fighting and a whole lot of horrifying moments.

So, when the game began, I heard Jack say, “They told me, ‘Son, you’re special. You were born to do great things.’ You know what? They were right.” But what I missed was the foreshadowing found in the neatly handwritten note attached to Jack’s gift. The note read, “To Jack with love, from Mom & Dad. Would you kindly not open until…”

While mono no aware may also be referred to as the “gentle sadness of things,” the aesthetic is tied to many emotions, including pain (Faena Aleph). While I hyper-focused on Jack’s words, on the idea of entering this underwater world and somehow saving it from its own self-destruction, I missed the destruction of a personal modus operandi happening right before my eyes with the innocuous turned insidious phrase, “Would you kindly…”

At the time of BioShock’s launch, this was a phrase I commonly heard. “Would you kindly pass the salt?” “Would you kindly relay a message to Beth?” “Would you kindly…”

During playthrough, the player first hears that phrase in the bathysphere following Jack’s descent into Rapture. It’s harmless.

“Would you kindly pick up that two-way radio,” Atlas says, radio static crackling in and out as he speaks.

As the game continues, in the player’s subconscious, a thought blinks in and out like the broken neon signs of Rapture: Atlas is your friend. Atlas guides you. Atlas will keep you safe.

It isn’t until after confronting Andrew Ryan that the player realizes the truth.

Atlas lied.

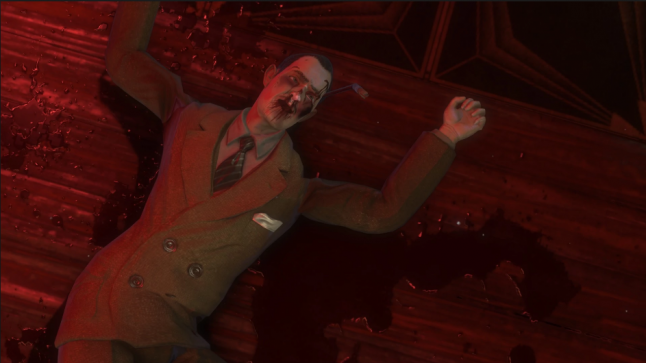

After fighting trial after trial and eventually gaining entry Andrew Ryan’s office, the player comes face-to-face with the enemy, the man seemingly behind the destruction of Rapture, a city of his own creation, and every life within it.

Only…that isn’t the whole truth. He wasn’t responsible for destroying the player’s life. He wasn’t responsible for the sad story behind Jack.

In the confines of Andrew Ryan’s office, the player learns everything leading up until that climactic moment was not a choice. It was a command. The player agency they thought they had leading up to that point, in majority, it was a lie. Instead, the player had little choice, finding themselves in what felt like yet another linear outcome with no chance of redemption or salvation.

“Would you kindly…?”

Andrew Ryan was a bad guy, but he wasn’t the player’s enemy. He was Atlas’s.

Andrew Ryan was a bad guy, but he wasn’t the player’s enemy. He was Atlas’s.

“Would you kindly head to Ryan’s office and kill the son of a bitch?”

And Atlas was the biggest lie of them all. Frank Fontaine created a lie to support another lie and twist the truth to propel the player forward following his will, not their own. In turn, the player was manipulated and, once Andrew Ryan revealed all, the trust they built with Atlas was gone.

Immediately after taking a golf putter to Andrew Ryan’s head, I remember having to pause the game to stop crying, to breathe. I was angry. Angry because I was deceived. Angry because I had no choice. But I was most angry because many of things Fontaine commanded, I wanted to do any ways and, even still, it wasn’t my choice. I was angry because, in the end, I didn’t want to kill Andrew Ryan and knowing that I had no freedom to decide if I did or not frustrated me.

Despite being a video game, I was devastated. I didn’t want to move forward.

But I had to.

I, like many others who played BioShock, moved on from that moment and completed the game.

Finding "home" in Gone Home

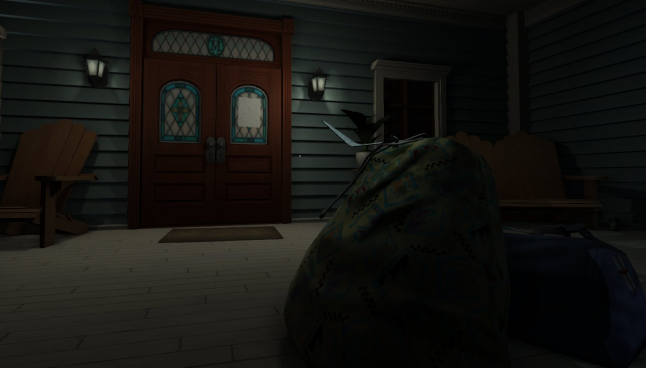

In August 2013, the Fullbright Company and Blitworks launched the first-person exploration walking simulator, Gone Home. Within the game, the player acts as Katie Greenbriar, a 20-some-year-old returning home only to discover no one is there to greet her. The player then must navigate her family’s new mansion and find clues to figure out what’s happened since she’s been gone and where her family is now.

In August 2013, the Fullbright Company and Blitworks launched the first-person exploration walking simulator, Gone Home. Within the game, the player acts as Katie Greenbriar, a 20-some-year-old returning home only to discover no one is there to greet her. The player then must navigate her family’s new mansion and find clues to figure out what’s happened since she’s been gone and where her family is now.

As the player looks through every nook and cranny in the house, the game’s narrative reveals uncomfortably intimate details of family’s life, including the father’s porn stash and mother’s potential affair. For me, it felt like I was unrightfully intruding and upturning this family’s personal belongings all for the sake of uncovering their story. In American society, these aren’t details we as individuals are supposed to see or, even, try to look for. As a culture, we encourage minding our own business and keeping our noses out of others’ personal problems. We might lighten to the whispering rumors of someone’s life details, but we don’t go through their houses trying to actively uncover it.

However, what’s important to remember about Gone Home is that the game developers are welcoming the player in to uncover the secrets behind the Greenbriar’s facade. And it really did feel like looking through my family’s own personal belongings.

Marty Sliva, a writer for IGN, said it best when he shared his thoughts on the game:

“As I rummaged through an abandoned kitchen examining refrigerator notes, discarded paperback books, and surprisingly named bottles of salad dressing, the proverbial light bulb suddenly illuminated.

Yes, I was exploring the Greenbriar home, a digital space where the first game by The Fullbright Company is set. But perhaps more importantly, I was exploring something strikingly similar to the house I grew up in. Each time I clicked on an item owned by a family member and studied its various traits, like empty liquor bottles belonging to a father who may or may not drink too much, or a sarcastically written term-paper on the female reproductive system that highlights a young woman's sharp wit, I was brought back to the uncountable innocuous nick-nacks that populate my parent's house.”

In his review, Marty finished by writing, “Gone Home presents us with a game that both embraces that melancholic notion while simultaneously exploring the roots, secrets, and artifacts of a family that feels as real to me as my own.”

While I concur with Marty’s thoughts, playing Katie nevertheless made me feel uneasy, but...

I grew to long to hear Samantha’s voice.

Voiced by Sarah Grayson, Samantha was this soothing, welcoming invitation to continue further into the otherwise uncomfortable game. After finding the first clue and her voice came through my headphones, I immediately felt a strange sense of connection to the character, like I was actually Katie or just Sam’s older sister and I had a reason to discover the dark truths behind the Greenbriars’ disappearance.

Voiced by Sarah Grayson, Samantha was this soothing, welcoming invitation to continue further into the otherwise uncomfortable game. After finding the first clue and her voice came through my headphones, I immediately felt a strange sense of connection to the character, like I was actually Katie or just Sam’s older sister and I had a reason to discover the dark truths behind the Greenbriars’ disappearance.

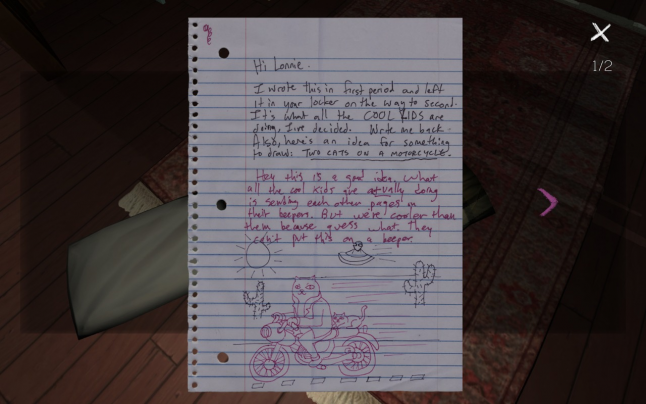

Each moment I had with Sam, I stopped moving to listen and be present as she spoke. And, after finding several clues, I realized that hearing her voice in snippets never felt long enough.

Mono no aware is present in Samantha.

As I discovered Sam’s bullying problem, her struggle to make friends and her romance with Lonnie, I felt a gentle sadness not only for the character’s story, but for the fleeting moments I had with the character or, more specifically, her voice. In the Greenbriar home, the empty space consumed me and only the family’s personal memories filled the gaps and voids in the otherwise vacant house. Of all the memories I wished I learn more of, though, I sought most for Sam’s.

The narrative designers cleverly crafted the game to only hint at Greenbriar parents’ internal thoughts and desires through well-placed alcohol bottles and letters from family friends. But it was different with Sam. There was a depth to her emotion, which became exposed in the cassette tapes, the video games, the handwritten notes, the trash and messes left behind, and, of course, her voice, which appeared only when I found the right clue to trigger the audio to play. For me, Sam was someone I felt that I already knew, long before I pressed play on the menu screen. To me, Sam was my little sister.

In my personal life, I’m the middle child of three. Now grown and gone our separate ways, I am rarely in contact with my older brother or younger sister. Much like Gone Home, my childhood home is empty and collecting dust. Much like in Gone Home, I am officially away from my family, left with only memories of them and their belongings to piece together the pasts that I missed before I set out on my own. Like Katie, I too am uncertain of the next time I will see my siblings that I grew up with, close to and, then, apart from.

In Gone Home, I knew the sisterly connection I felt with Sam was, in some way, eventually going to end. I just didn’t know how until that moment occurred. So I did my best to appreciate it while it lasted.

This is mono no aware.

The emotional journey in The Last of Us

First of all, Naughty Dog had no right to emotionally break their players like they did in June 2013 with the release of The Last of Us.

In this zombie-esq survival, action-adventure, horror game, the player takes on the role of Joel, a gruff old man tasked with surviving an infected and destroyed civilization while smuggling teenager Ellie to the Fireflies, a rebel militia group that openly oppose quarantine zone authorities.

Or at least that’s what the game’s trailers would have everyone believe.

Instead, the player starts out as Sarah, Joel’s daughter. After an opening cutscene where the narrative establishes a bond between the two characters with a thoughtful birthday present, Sarah awakens to a frantic call from her Uncle Tommy, who commands her to put Joel on the phone.

Instead, the player starts out as Sarah, Joel’s daughter. After an opening cutscene where the narrative establishes a bond between the two characters with a thoughtful birthday present, Sarah awakens to a frantic call from her Uncle Tommy, who commands her to put Joel on the phone.

The line eventually goes dead before the player learns what exactly is going on and they take control of Sarah from a third-person perspective. As the child, the player nonchalantly walks around looking for Joel. Sarah’s arms swing as her character casually moves from room to room through her house. As she listens in on a news broadcast and hears explosions, the character’s body language increasingly tightens up and exhibits signs of anxiety and worry as she can’t find Joel.

Eventually, the player finds him running through the backdoor, covered in blood and the player gets thrown into the game’s primary setting: infected world.

Sarah and Joel flee from their home with the help of Uncle Tommy only to find themselves in the middle of panic and chaos caused by an outbreak of the Infected. Following a violent car crash, the player finally takes over Joel and, being father, carries his daughter to safety.

However, the fatherly moments don’t last much longer as, within a few minutes of escaping the chaos, the player watches as Joel cradles Sarah in his arms. She whimpers in pain and blood spills from her body from where she took a bullet to her stomach.

Sarah dies, and she isn’t the only one in the game that will.

The Last of Us uses mono no aware to make the player devastatingly aware that, like with people in their real lives, they should appreciate the moments they have with Joel’s non-player character (NPC) companions.

Everything ends. Mono no aware is understanding there is privilege in experiencing things and people before they are gone or dead.

What makes The Last of Us most painful, however, is the game’s use of the

What makes The Last of Us most painful, however, is the game’s use of the (written in this document as shin, gyo, so), a Japanese aesthetic and narrative mechanic that uses “empty spaces” strategically to make certain moments more powerful.

According to Richard B. Pilgrim’s article “Intervals in Space and Time” in the book, “Japan in Traditional and Postmodern Perspectives”:

"Rather than construct a logical and linear narrative order, as Western languages do, Japanese carries internal gaps and pauses (e.g., haru wa…) and fixed endings (e.g., desu) that create distinct spaces that are, in turn, filled with ki (ke; Chinese: ch’i) or emotional energy.

[With shin, gyo, so] … The light that thus shines through [the empty spaces] is the meaning and power of such imaginative or emotional “negative spaces” that dissolve the narrative, cause/effect world being presented.”

In The Last of Us, these gaps go unconsciously noticed by the player. The player may feel connected to Joel and thus sense a void that is left behind by Sarah’s death and, eventually, Tess’s in the first few hours of gameplay. For me, I only consciously noticed these intentional gaps when I returned to critically analyze the game for this article.

Following Sarah’s death, there is an obvious emotional void present in Joel’s demeanor. In the story, the shift between loss and numbness took place over the course of 20 years, but for the player, the shift happened within a few seconds.

Heartbreak transitioned, seamlessly, straight into cold-heartedness, and the player was right there for it.

The use of mono no aware and shi, gyo, so in The Last of Us makes the player feel this unnerving anxiety that they may be keeping Ellie alive in the moment, but worry about her death being on the horizon.

Appreciate Ellie but know she may be gone in a flash.

This is one of the many reasons it is such a good game, in my opinion.

Closing thoughts

Coming from a culture that does not regularly discuss death or unhappy occurrences, the idea of practicing mono no aware in everyday life seems, in theory, calming. Using the aesthetic in game design, on the other hand, seems like an interesting tactic to encourage players to immerse themselves within a virtual world on a deeper cognitive level, one of careful observation and appreciation for all the moments presented in game.

Bioshock used it by providing the player with a false sense of security of their freedom within the game. Gone Home’s Samantha meanwhile encapsulated the aesthetic in her voice. The Last of Us devastated players by reminding them that, yes, life even within video games can also be impermanent and, therefore, appreciate the moments experienced with others instead of wallowing in self-pity and numbness, which inhibit the ability to live fully.

References

Trommsdorff, Gisela, and Fred Rothbaum. Development of emotion regulation in cultural context. Bibliothek der Universität Konstanz, 2008.

Faena Aleph. Mono no aware: The gentle sadness of things. www.faena.com. Feb. 6, 2016. Accessed Feb. 12, 2019.

Sliva, Marty. “Gone Home Review.” IGN, www.ign.com/articles/2013/08/15/gone-home-review. Aug. 15, 2013, Accessed Feb. 12, 2019.

Fu, Charles Wei-hsun, and Steven Heine, eds. Japan in traditional and postmodern perspectives. SUNY Press, 1995.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like