Examining Game Design from the Perspective of "Behavior Analysis" the Red-headed Stepchild of the Psychology World

Examining Game Design from the Perspective of “Behavior Analysis”

*This article was originally written by Japanese indie game creator Daraneko, and translated by PLAYISM.

Behavior analysis is a rather unusual field of psychology. To put it bluntly, it’s kind of like...

“The ‘mind’? What’s the point in looking at something so uncertain and vague?

Forget that stuff, let's focus on "actions" that can actually be observed and measured!”

As a discipline of psychology, it has taken quite a drastic left turn, in a way.

It is also a very practical discipline.

--------

Alright, so "playing video games" is one type of behavior. In other words, if we understand the "mechanism of behavior" studied in behavior analysis, we can further deepen our understanding of the behavior of "playing video games".

OK that sounded way too stuffy. I get tired just writing stuff like that out. Anyway, I found some info that might be useful for making games, so I'll touch on that stuff here as I contemplate it myself. Here we go.

Table of Contents

The Point of this Article

Fact #1: The cause of a behavior lies “after the behavior”

Fact #2: Thinking of "behavior" in terms of "behavioral contingencies"

Fact #3: Four basic principles of behavior

Fact #4: Behavior “increases” (reinforcement)

Fact #5: Behavior “decreases” (disinforcement)

Implementation (Digression): “Reinforcement” is a game’s foundation

Fact #6: Extinction and reversion

Fact #6 – Extra: That thing where you get to the end of the game but lose motivation

Fact #7: The nature of extinction and types of reinforcement

The Point of this Article

This time, since we're dealing with behavior analysis, I won't set a target of "making interesting games". Instead, the target is to increase a player's behavior of "playing the game" (an extremely fun game I made myself).

We're not aiming for "fun", but imagine a situation in which a player "keeps playing the game on and on". As a game designer, I think this is a great situation.

First off, I will introduce the above-mentioned info on behavior analysis in "Fact" sections, using games as examples. Then, based on these facts, I'd like to discuss how this stuff can be applied to game design as an example.

So for now, let's start with the explanation.

Fact #1: The cause of a behavior lies “after the behavior”

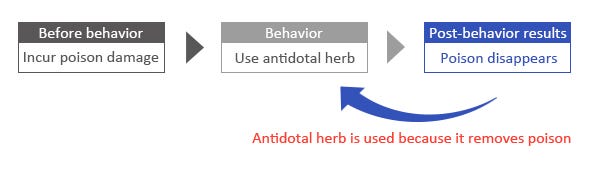

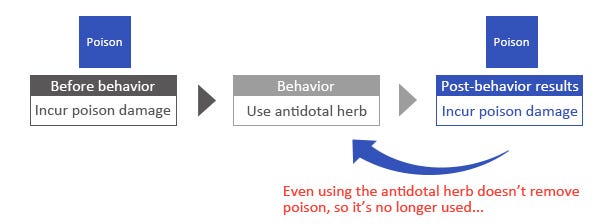

Just looking at the title of this section, you’re probably like, “What the hell are you even talking about?” But that’s fair. Anyway, if you’ve played a lot of RPGs, then you’ve probably used some sort of “antidotal herb” at some point. Well, why did you use this “antidotal herb”? Why not use a “medicinal herb” or something instead?

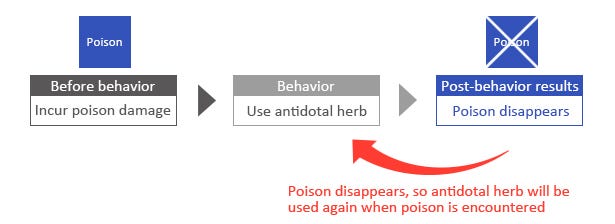

Why do people use “antidotal herbs”? Well, because it’s there... Just kidding; it’s not that simple and vague. They use it to relieve themselves of the crappy status ailment known as “poison”. Let’s put it into chart form:

The reason for the action of "using the antidotal herb" can be said to be due to the fact that "the poison will disappear after using the antidotal herb". So, the antidotal herb is used with the expectation that the poison will disappear.

Now you're probably saying, "What the hell are you talking about? Like, no duh."

This kind of behavior, in which the cause of occurrence comes after the action, is called "operant behavior". You don't have to bother remembering this name, as it won't be on the test.

All human behavior, except for reflexive behavior, falls under operant behavior. (Reflexive behaviors are things like crying because of dust in your eye, Pavlov's dog, stuff like that.)

So what I'm trying to say is, if you design a game so that the behavior of "playing the (super-duper fun and awesome) game (that I totally made)" increases in accordance with the operant behavior mechanism, then theoretically, people will be more willing to play the (super-duper fun and awesome) game (that I totally made). Theoretically, I mean. It's pretty amazing, isn't it?

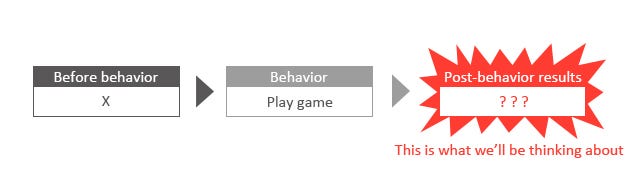

Fact #2: Thinking of "behavior" in terms of "behavioral contingencies"

So we've discussed operant behavior. Let's get to know a bit more about how it works. Earlier, I showed you this diagram as an example using antidotal herbs.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

In operant behavior, there is a very strong connection between "action" and "result," as in "I used the antidotal herb, and the poison disappeared. So if I get poisoned, I'll use the antidotal herb." In this way, "action" and "result" are very strongly connected.

Behavior analysis places a great deal of importance on this connection, and the basic idea is to consider "before action", "action", and "result after action" as a single set. This is what is technically known as a "behavioral contingency". If you want to influence someone's behavior, you have to think about what to do with the "result after action".

Fact #3: Four basic principles of behavior

When I mention "influencing someone's behavior," I don't mean it in an overly dramatic way. There are two simple things to consider: how to "increase behavior", and how to "decrease behavior". The first thing to understand is that there is something that explains the general framework.

First off, for increasing behavior, this is called "reinforcement". There are basically two ways to do this.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Reinforcement: Behavior increases

・Positive reinforcement: (reinforcement through provision of a reinforcer)

⇒Acting causes “good things to happen”, therefore behavior increases

・Negative reinforcement: (reinforcement through removal of aversive conditions)

⇒Acting prevents “bad things from happening”, therefore behavior increases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

The next step is to reduce behavior, which is called "disinforcement". There are two basic ways to do this as well.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Disinforcement: Behavior decreases

・Positive disinforcement (disinforcement through provision of aversive conditions)

⇒Acting causes “bad things to happen”, therefore behavior decreases

・Negative disinforcement (disinforcement through removal of a reinforcer)

⇒Acting prevents “good things from happening”, therefore behavior decreases[/i]

――――――�――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

Elements that affect these “reinforcements” and “disinforcements” are known as “reinforcers” and “aversive conditions”, respectively.

Think of a “reinforcer” as a kind of “reward”; basically, something that will make the receiver happy.

The opposite is true for "aversive conditions", which would be something more off-putting, like a penalty. "Poison" would be an example of an “aversive condition”.

By the way, "poison" can also work as a "reinforcer" in a situation such as "I want to use a skill that will be greatly enhanced if I become poisoned". It's just a matter of "whether it makes you happy or unhappy" in a particular situation.

Allow me to explain each of these reinforcers and aversive conditions.

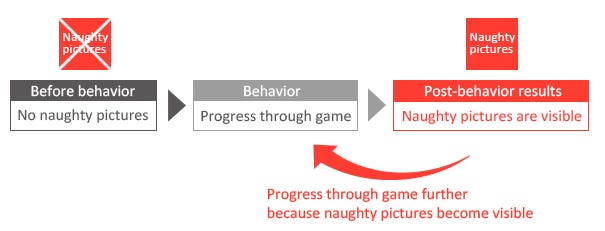

◆Fact #4: Behavior “increases” (reinforcement)

First, let's talk about reinforcement, the principle of increasing behavior.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Positive reinforcement (reinforcement through provision of a reinforcer)

⇒Acting causes “good things to happen”, therefore behavior increases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

The most obvious, healthy, and powerful is this "reinforcement through promising a reinforcer". If you get rewarded for your actions, you will do more of that behavior.

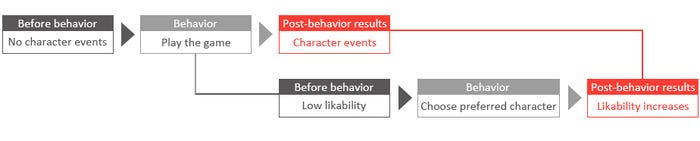

I think "eroge", or "sexy games", are easy to understand and would make a good example. As a chart, it would look like this.

Even if the scenario is relatively toned down, or the game itself is a rather boring, if you - as the player - can get your hands on an image that you find to be super hot, then that's a strong example of a “reinforcer” and you're gonna work hard to get it. (Also, you nasty.)

Alright, moving on.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Negative reinforcement: (reinforcement through removal of aversive conditions)

Acting prevents “bad things from happening”, therefore behavior increases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

This is the same example as the antidotal herb thing that I've been using. Since we want the “aversive condition” represented by poison to be gone, we use the antidotal herb.

This is the kind of thing you do because you don't want to "lose" anything.

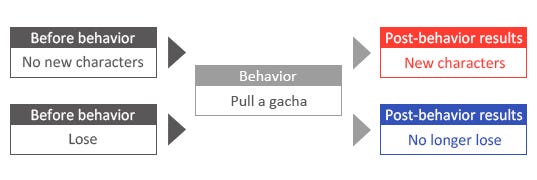

In this case, "pulling a gacha when a new character appears" is also included in "reinforcement through removal of aversive conditions". Since reinforcement and disinforcement are compounded, in this example, the behavior of "pulling the gacha" is reinforced by two reinforcements: the reinforcement of the appearance of a new character, which is a provision of a reinforcer, and the reinforcement of the removal of aversive conditions, which is that you will lose if you don't get the character. Gacha can be scary.

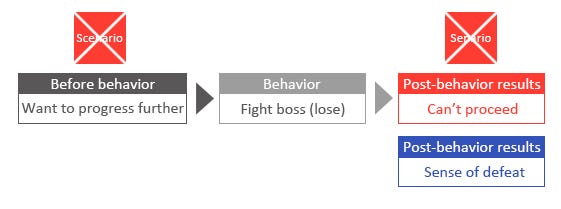

◆Fact #5: Behavior decreases (disinforcement)

Next is disinforcement, or the principle of decreasing behavior.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Disinforcement: behavior decreases

・Positive disinforcement (disinforcement through provision of aversive conditions)

⇒Acting causes “bad things to happen”, therefore behavior decreases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

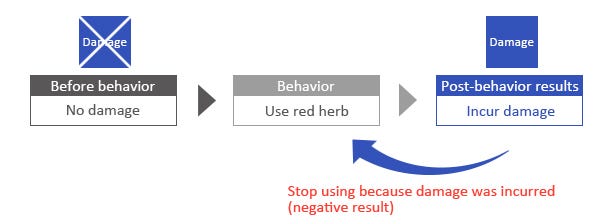

This means that you refrain from performing certain actions if you know you’ll be penalized for it.

Like, say you acquire some "red grass", and you try to use it and you end up taking damage... You won't try using that "red grass" again. Also, if you are constantly losing in a competitive game, you will stop playing that game.

OK next. Let’s burn right through these.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Negative disinforcement (disinforcement through removal of a reinforcer)

⇒Acting prevents “good things from happening”, therefore behavior decreases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

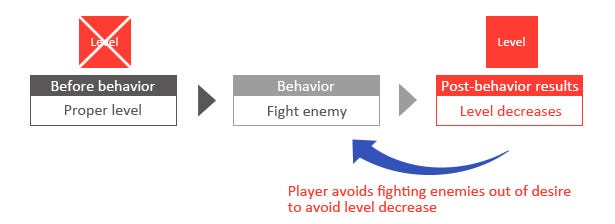

This one is pretty hard to explain. I’m not a fan of this one.

But my feelings here don’t matter. Anyway, to give an example, if the more you fight enemies, the lower your level drops, then you’re gonna stop fighting altogether... That. That’s pretty much it.

Another example of negative disinforcement is when your mom says “You’re not getting any snacks if you play more than an hour of video games per day!”

◆In Practice (Digression): “Reinforcement” is a game’s foundation

These facts are gonna continue for a little longer... But I don't want to keep droning on with explanations too much. I'd like to touch on how reinforcement and disinforcement can be applied to game design.

First, let's go back to the goal I mentioned at the beginning of this article. Here it is.

Also, this time, as is the case with behavior analysis, our goal will not be to "make a fun game". Instead, the goal is to increase the player's behavior of "playing the (super-duper fun and awesome) game (that I totally made)".

Increasing behavior is reinforcement. So, in game design, it is very important to think about how to reinforce the behavior of "playing the (super-duper fun and awesome) game (that I totally made)".

For example, let's think about "leveling up. It's used in all sorts of games, right? Level up. When you level up, your status increases and you learn skills, so it is easy to use as "reinforcement through provision of a reinforcer". As an example, think of a game with a bit of level-up action. It can be a game you like, a game you dislike, or even your own game.

.

.

.

OK. So, is leveling-up in that game actually fun? Do you feel satisfied when you level up? Does it make you feel like you want to go and level up even further?

To put it a different way: how strong is the “reinforcer” provided when leveling up?

I know it's probably hard to imagine, so let’s set up a rough guide for this “strength”.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

[ S Rank ]

I enjoy playing this game so much that I end up leveling up. I actually play this game specifically for the sake of leveling up.

[ A Rank ]

I'm happy when I level up, and I can set "goals" like "I want to get to level XX".

[ B Rank ]

I feel that I'm getting stronger as I level up, and I'll be happy when my level goes up.

[ C Rank ]

It's good to have a high level, but I don't really think about it that much.

[ D Rank ]

Leveling up doesn't fully function as a "provision of a reinforcer". It has become unimportant.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

If you want to reinforce something, of course, you should have a strong "provision of a reinforcer", and conversely, a weak "provision of a reinforcer" is not useful for reinforcement. The stronger this “reinforcer” is, the better.

If I were to use my own rough guide above, I would say that a rank of B or higher is desirable, and if you are going to put a lot of effort into that content, you should use something ranking A.

On the other hand, if it's C rank or lower, it needs to be tweaked or it's just a useless feature, so you might want to consider removing it.

In this case, I used level-up as an example, but if you thoroughly peruse and judge whether or not this “reinforcer” is functioning properly for every element of the game, you will be able to see what needs to be fixed in the game.

It can be good to handle a large framework in subdivisions, for example, when evaluating a "character enhancement system" in subdivisions.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Level up [C]

When your EXP reaches a certain level, your level will increase and your parameters will rise. The amount of increase is more modest than that of equipment.

◆Updating equipment [A]

Obtained in armory shops and dungeons. When you get new equipment, your parameters will increase significantly. Due to its high importance, it works well as a strong reward.

◆Learning skills [A]

You learn skills as you get used to them and as your skill level increases. The higher-level skills are clearly stronger and become the goal of raising the skill level.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

In this case, leveling up is weak, because the role of "parameters increase" is already covered by equipment updating, and it's not as good as that either, so its function as a "provision of a reinforcer" is weak. There are a few ways to fix this, such as "include a parameter that only increases as you level up" or "change the skill level increase to be done with points obtained through leveling up".

As an example of how to use this, you can use it to "evaluate" a game in this way. You don't need to know anything about behavior analysis to do this, but naming concepts like "reinforcement" and “reinforcer” makes it easier to fully grasp. Since you can measure every element of the game on the same scale, it's easy to spot areas that need to be leveraged.

So, uh... yeah.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Well, sure, this stuff can be used for evaluation, too, but...

Just how exactly can it be used for game design itself?

------------------------------------------------------------------------

This is probably what you’re thinking right now, isn’t it? Yeah, I can tell. I was afraid of that.

It's not that I can't explain that stuff, but I need to toss out a couple more of those facts first. Otherwise my explanation is gonna come out all half-baked. So please join me once again for a little more of that "Facts" section.

◆Fact #6: Extinction and reversion

I have explained four basic principles of behaviors contingencies, but there are two more.

What do you think would happen if a behavior that was reinforced became unreinforced after a certain point? For example, if poison was no longer cured by using the antidotal herb. Or like, you were no longer able to look at naughty pictures while playing your game.

I think you can sort of guess the answer, but it reduces the frequency of that reinforced behavior. It's not worth it to use an antidotal herb that doesn't relieve poison. An eroge without naughty pictures may be a perfectly healthy, wholesome game, but it doesn't satisfy the desires of the horny weirdos who just need to get their porn game fix. The frequency of reinforced behaviors does not last forever, and if the results continue to be disappointing, the reinforcement will eventually disappear. So the once-increased behavior returns to normal frequency.

This is called "extinction". It is often confused with the "disinforcement through removal of a reinforcer", but that one is "the disappearance of what was already there", while this one is more like "the failure of what was supposed to be newly available to appear".

By the way, there is a similar thing with disinforcement. If you think something bad will happen if you perform an action, and you try said action, and then nothing bad happens, the behavior that had been decreasing returns to normal. It increases. This is called "reversion".

.

.

.

Now, I know that many of you are reading this with a "hmmm". This "extinction" tends to be an invisible trap for game designers. If you are not careful, you'll end up getting stabbed from behind. I'll explain what I mean here.

◆Fact #6 – Special Edition: That thing where you get to the end of the game but lose motivation

One of the most common things people say about games is, "I've made it all the way to the end of the game, but I've lost my motivation and haven't beaten the last boss." This is exactly where "extinction" plays a bad role.

Recently, I felt this strongly with the new Fire Emblem game (Three Houses)

. I don't like to use other people's games as examples, but, well, it's a good example, so...

When I play a fun game, I tend to play it continuously, and the first day I bought this game, I played it all day long. However, the frequency of my playing gradually decreased, and by the end of the game, I only felt the need to play it once every few days.

Let's analyze this in terms of behavior. To analyze it, let's summarize the “reinforcer” evaluation of this game. My personal evaluation of the beginning of the game is as follows.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Class change [ S ]

Your abilities collectively increase greatly, making you stronger and changing your appearance. This is quite important because it changes your movement type and you can acquire skills by mastering a class. This is the key to training, and the class you choose for your character will greatly affect your training methods.

◆Level up [ A ]

You have to be above a certain level in order to change classes, so stuff like "I want to get to level 20" ends up becoming a goal. The early stages of the game are also highly affected by ability increases.

◆Skill level [ A ]

It is necessary to learn new active and passive skills. It also affects the success rate of class changes, and the main character's skill level is also necessary for scouting (making characters friends), so you can set goals like "I want to get my sword skills to B". This stuff is important.

◆Character likability [ A ]

As likability increases, you can see specific events for the characters and it also affects battles as well. Not only is there a likability level for the main character, but there are also likability levels and events between characters, so you can try your best to raise these.

◆Scenario [ B ]

I knew that the three groups that were getting along reasonably well would eventually fight... So I was looking forward to seeing how that would play out. It also serves as a type of “reinforcer” to a certain extent, as your scenario choices can increase the likability of the characters.

◆Guidance level [ A ]

This is an essential element for raising skill level and likability, and its importance is quite high as it affects them quite deeply. Whenever I had extra actions to perform along my way, I would always try to raise my guidance level.

◆Equipment upgrade [ C ]

While I'm happy when I get equipment that looks strong, the system makes the initial training equipment pretty good (I used this to kill goombahs even at the end of the game), so even if I'm able to get something cool, it often can't easily be upgraded, or I end up not using it due of its durability.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

It's basically a whole bunch of “reinforcers”, although a little weak in the equipment department. As a result, my behavior had been reinforced and I continued playing the game for a while.

Next is my evaluation for the end part of the game.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Class change [ C ]

I've already completed the class change for the top-level job. And when you max out a higher-level job, you get a skill that is exclusive to that class, and you're like, "You can't use that in a top-level job..." and a little bit of extinction occurs.

◆Level up [ C ]

While it is nice to see abilities increase, the rate of growth is the same as in the beginning, so the importance is not as high as it should be.

◆Skill level [ D ]

I'm almost done, and there are some left, but I don't really feel the need to try to improve or acquire anything else.

◆Equipment upgrade [ D ]

I've got all the strong equipment I need for the moment, and I don't need to force myself to update it.

◆Scenario [ C ]

Unfortunately, I couldn't get that emotionally involved with the characters, and the choices were becoming more and more pointless, so I wasn't really interested in seeing what happened next. (I think I made a mistake in choosing my route.)

◆Character likability [ D ]

My character's likability is maxed out, and actual likability doesn’t increase any further.

◆Guidance level [ D ]

I’ve already maxed out my level so whatever.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

Yeah. So there isn't a single B rank, and you can see that my evaluations have dropped a lot compared to the beginning. And to think how chock full of “reinforcers” it was.

Note that although the “reinforcer” of the training system is very powerful and very easy to create, once levels are maxed out and there's no longer any need for training, it becomes pretty much pointless. As a result of the capping out of the training part, the “reinforcer” has been basically eliminated, and there is no longer a "reason to play this game". That's why people quit games even after having advanced all the way to the endgame.

The player has high enough levels, the strongest weapons, and the most powerful skills, and all they have left to do is take on the last boss... So now, you may be pretty screwed as far as player retention goes. As a game designer, you should also think carefully about how to create reasons (“reinforcer”) to play the game up through the endgame.

◆Fact #7: The nature of extinction and types of reinforcement

So I've explained the horrors of extinction. As for extinction, if you don't get the expected result, it doesn't mean that your behavior will immediately decrease. There is something called "resistance to extinction", and if the resistance to extinction is strong, the behavior will not decrease easily. (Incidentally, there is no such thing as "resistance to reversion", which I guess would be the opposite of resistance to extinction.)

So what kinds of things have strong resistance to extinction? There are two types of reinforcement: "continuous reinforcement" and "partial reinforcement", and each type of reinforcement has a different resistance to extinction. The characteristics of each type are as follows.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Continuous reinforcement

Reinforcing the pattern of getting the “reinforcer” every time you do a specific action. This is the one where you get experience when you defeat an enemy. The resistance to extinction is weak, and when you don't get the reward that was there every time before, the behavior will be reduced more quickly.

◆Partial reinforcement

This is a reinforcement of the pattern where you may or may not get the “reinforcer” when you perform a specific action. This is the kind of reinforcement where you get a rare drop of powerful equipment after defeating an enemy. The resistance to extinction is strong, and since it's a reinforcement that may or may not provide a “reinforcer” in the first place, it's less likely to reduce the applicable behavior even said reinforcer isn't provided every time.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

Partial reinforcement is the deeper one here. Gambling and capsule toy machines are also very powerful forms of partial reinforcement. Also, the reason I make games even though they don't pay off every time is because I used to get so much positive feedback from reviewers, like "Thanks for a great time!" This is also a type of partial reinforcement.

Looking at it this way kinda makes me feel like I should just make all the elements into partial reinforcements...

You need to have the target try until partial reinforcement occurs (until you get the reinforcer), and (and this is just my guess, since it wasn't clearly written in some book) it is preferable to have a strong example of a reinforcer for reinforcement rather than continuous reinforcement.

If you have to work really hard to get a strong weapon in a rare drop, and the weapon you get is only slightly stronger than the one sold in the store, then no one will bother to work hard for that weapon.

By the way, there is a property of extinction called "extinction burst" which is sort of like a special move. To explain it very simply, when you press the attack button and no attack occurs, just keep mashing the attack button again and again... This is an extinction burst. It's an explosion of actions before the extinction. It's not really relevant to this story, so I'll spare you the details. But if you think you can make it work out, by all means go ahead and try it out.

◆Fact #8: Time up to releasing the “reinforcer” and “aversive conditions”

Reinforcement or disinforcement occurs when a "reinforcer" or “aversive condition” appears after an action... So how exactly should one time "after an action"?

To sum it up, the sooner after the action, the better. To give an extreme example, the reason you are happy when defeating a metal slime is because "you get a lot of EXP after defeating it". If it's done in such a way that you get a lot of EXP 30 minutes after defeating it, this sense of happiness is going to fade significantly.

If I had to give a clear guideline, I'd say "within 60 seconds". There are no clear boundaries here, so it's really just a guideline. Basically, it's good to show the reinforcer or aversive condition to the player immediately after the applicable action.

For example, if an event choice increases the player-character's likability, it is preferable to tell the player about the increase in likability when they make that choice - not after the event is over. Get it out there as soon as possible.

◆In Practice #1: What a game designer must consider

Well, the super-long "Facts" section is finally over. Now let's use these facts to think about game design. First of all, as I mentioned earlier, there are two main things that a game designer must consider.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆How to increase “game playing” behavior

The game should have elements that "increase said behavior" using "positive reinforcement", "negative reinforcement", and "reversion". If this part of the game design is done half-assedly, there will be no reason for players to want to go on playing that game.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Eliminating elements that reduce “game playing” behavior as much as possible

Thoroughly eliminate from the game any elements that can be considered "positive disinforcement", "negative disinforcement", or "extinction", and remove any elements that "reduce said behavior". Note that containing too many of these elements will make the game basically "unplayable" for a lot of players.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

Simple. Now we need to consider what we should do in order to achieve these goals.

◆In Practice #2: How to create a “reinforcer”

How do you make the “reinforcer” required quickly? The quickest way is to set up a goal and a means to achieve it. It's a real joy to find yourself moving closer to a goal you've set for yourself.

The so-called "token economy method" is also used in clinical settings in which behavior analysis is applied (for example, to improve truancy, etc.). It's like a point card, where if you accumulate a certain number of points (tokens), something good will happen to you, so you feel motivated to take the required actions to accumulate points.

These "tokens" aren't useful on their own, but if you accumulate enough of them, you will be rewarded. Like stuff like EXP and likability. Be sure to use these things well.

For example, when a goal is created, such as "get a likability rank of A in order to see an event," the "likability rank" becomes a token ("the reinforcer"). As shown in the figure below, the composition is somewhat hierarchical.

Now, when it's time to actually create the goal, make sure to make the "goal" a very specific goal. For example, a goal such as "increase the character's level to 10" is easier to aim for than just "increase the character's level".

Also, it is important to be specific and clear with regard to the "means to achieve the goal". If you want to get to level 10, but you don't know how to gain EXP, then your goal is meaningless. There is no way to achieve it.

In the case of Fire Emblem, which I mentioned earlier as an example, there are a lot of things hanging in the air when it comes to class changes.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Class change

・ Above a certain level ⇒ Reinforcer: EXP

・ Class-based skill level ⇒ Reinforcer: Skill EXP

・ Item used for class change ⇒ Reinforcer: Items, money

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

This is a good example of how various elements in a game can function as a “reinforcer” by having multiple small goals dangling from the larger goal of a class change. It's not just a matter of having a lot of them hanging around (because it gets complicated and confusing); it's easy to associate "class change" with "skill level", so it's good that the game isn't confusing even with a lot of elements to consider.

◆In Practice #3: Combining continuous and partial reinforcement

Of course, you should use both continuous and partial reinforcement according to specific characteristics present, but it is also possible to use a combination of both. You can use continuous reinforcement to handle some parts and partial reinforcement for others.

For example, in Dragon Quest, you basically get EXP by defeating enemies (continuous reinforcement), but if you can defeat the occasional metal slime, you can get a lot of EXP (partial reinforcement).

In Monster Hunter, you basically get materials by defeating enemies (continuous reinforcement), but sometimes you can get very rare materials like plates and such (partial reinforcement).

So yeah. I tried to think of a good way to end this part, but I couldn’t come up with anything so, uh, I’m just gonna go ahead and move on to the next part. Here we go!

◆In Practice #4: How to avoid “reduction in behavior”

I've already talked about extinction in "Fact #6 – Special Edition". In the last half of the game, it's easy to run out of “reinforcers” and face extinction, so you have to be careful.

So, what should we do to handle the disinforcement aspect?

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Positive disinforcement (disinforcement through provision of aversive conditions)

⇒Acting causes “bad things to happen”, therefore behavior decreases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

As for positive disinforcement, I guess I'd say that we should eliminate elements that cause unnecessary stress. For example, "loading screens that are too long", "slow movement for no reason", "encounter rates that are too high", "confusing UI", and so on. Even if each of them doesn't have that big of an impact alone, they all add up to make a bad game in the end. Fortunately this isn't as common in recent games, though.

In competitive games, it's better not to make "losing" into a big example of an “aversive condition”. If you keep losing, you will get sick of playing and quit. This is especially true for board games. It is quite stressful to play a game when you don't think you can win. On the other hand, if you can make the player think, "I lost, but at least I had fun," then they won't be so turned off.

If you want players to try to win, it's probably healthier and less likely to turn players off if you use reinforcement by increasing the rewards for winning, rather than increasing the penalties for losing and using disinforcement.

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

◆Negative disinforcement (disinforcement through removal of a reinforcer)

⇒Acting prevents “good things from happening”, therefore behavior decreases

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

About this one... Um, to be honest, I don’t really have many ideas on this...

I think it's best to "not do anything that would discourage the player". For example, a companion who is leaving the game permanently is holding some super valuable equipment, and that equipment is lost forever when they leave. Stuff like this.

If anyone out there has any good ideas, please quietly let me know (so this is on you guys now).

------

I mentioned that it's good to evaluate "how strongly the 'reinforcer' is functioning" with regard to reinforcement, and the same is true for disinforcement. It might be a good idea to evaluate whether there are any elements that could be considered "disinforcement" when playing the game.

◆In Practice #5: Why people play extremely hard games

There are games that are popular despite their high difficulty, you know? A famous example would be Dark Souls, and a more recent one would be Sekiro.

Why does everyone like to challenge themselves so much? I mean, you might not even be able to win. Even if you just want to enjoy the story, you can't because of the high difficulty, and extinction or disinforcement are likely to become issues due to the all the stuff that could be considered an “aversive condition”. It feels like it would be a no-win situation for the developer.

So, is everyone just a masochist or what...? Well maybe, but this isn't really a "behavior analysis"-type viewpoint. These games are actually popular, and I, too, like to play and create games with high difficulty levels. In science, reality always takes precedence. If this stuff is popular in reality, then it must have behavior contingencies that make it so.

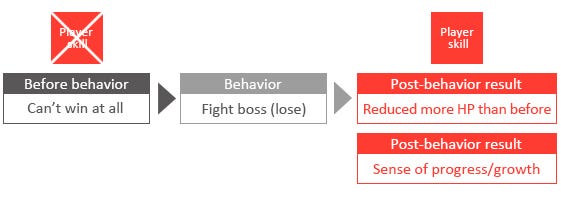

The fact that the behavior is maintained without reduction means that there is either some form of reinforcement after defeat, or there is a strong resistance to extinction. As it turns out, it's both.

-----

First, let's start with the reinforcement when you are defeated. If I randomly try to think of something common in boss battles in difficult games, there's one thing that pops into mind right away: the boss enemy's HP bar.

This plays a surprisingly important role. When you play a difficult game, you may not be able to do very well at first, but the more you play, the better you get. The boss's HP bar shows you how much you have improved in an easy to understand way. Even if you keep getting killed over and over, you can see that you have reduced your enemy's HP more than before, and that you are getting better, so it is easy to see how much you have grown, which constitutes a type of “reinforcer”. Everyone looks at that HP bar, right?

In other words, in a game where you have to try again and again, it is important to make the player feel that he or she is getting better than before and has made progress even when defeated. This sense of growth becomes a type of “reinforcer”, and it reinforces the behavior even if the player loses. So even if you lose many times, you can continue to fight without giving up.

By the way, I'm not saying that you absolutely have to display the boss enemy's HP bar. You just need to know how far you've progressed, so it's good if you can feel your progress by seeing how your enemy looks when they're damaged, or how their dialogue changes.

The battle against Sans in Undertale is very well done, in that there is no HP indicator, but the dialogue changes according to the number of turns. It's a boss battle of unbelievable difficulty, but there are also a lot of other mechanisms to make the player want to retry, which is great. It's a good learning experience.

-----

Next, let's talk about strong extinction resistance. If there is a strong resistance to extinction, then there is partial reinforcement. What can act as a kind of “reinforcer” is a sense of accomplishment. You can't win every time, but the sense of accomplishment you get when you try and win again and again works as a strong example of a “reinforcer”. Or something like that. Oh, and just to be clear, that "sense of accomplishment" is just one example of many possible types of “reinforcers”.

Yes. Giving the player a sense of accomplishment. Sounds really good, doesn't it? Hahaha.

In other words, what game designers need to do is figure out how to train players through partial reinforcement. They pick up on the line at which the player feels "this is hard, but I can do it," and train the player to experience the joy of victory through hard work. This is how game designers create tough players who will not be daunted by defeat.

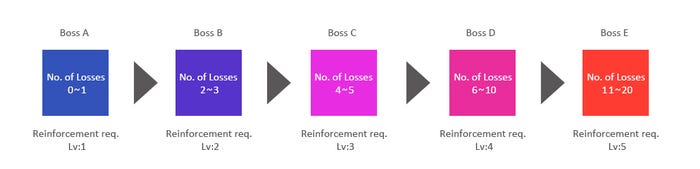

OK, so, how do we train players? A technique that is often used in conjunction with the token economy method is called "shaping". A rough explanation is as follows.

◆Shaping

A method of reinforcing a specific behavior by starting with a task of low difficulty and gradually increasing the difficulty.

Think of it as players having a "reinforcement level" where they challenge difficult games over and over again. The higher the level, the more difficult games they have played in the past, and the more they know the taste of "accomplishment".

Now, if you suddenly hit a person with a low reinforcement level with an enemy of a high difficulty level, their heart will break. They'll get knocked out. So, you need to hit them with relatively low-difficulty enemies first to raise the player's reinforcement level. Here's a diagram.

The only people who can endure something like Boss E out of nowhere are those who like very high-difficulty games. It would be a pretty niche game.

So, start with Boss A and gradually increase the difficulty level, and give players a sense of accomplishment when they defeat Boss B, Boss C, and so on. If you release Boss E when the players are properly trained, even if they only started off at reinforcement level 1, they will keep playing the game because they have progressed up to the 5th reinforcement level by that point. They know the taste of accomplishment.

By the way, this idea is not limited to enemies of high difficulty. It's a good idea to start with easy reinforcement and let the player get a taste of the difficulty curve, and then gradually make it more difficult, as it's an effective way to increase some kinds of behavior.

Wrap-up

That's it for now. I feel like this was about ten times harder to write than my usual articles. By the way, the actual number of words is almost five times as high as usual...

Let’s wrap all this stuff up, shall we?

------------------------------------------------

Facts

The cause of a behavior lies “after the behavior”

A “reinforcer” is the player’s reward

An “aversive condition” is a negative thing that act as a penalty

Behavior changes when reinforcers or aversive conditions appear or disappear after certain behaviors

Behavior increases after said behavior ⇒ “reinforcement”

Behavior decreases after said behavior⇒ “disinforcement”

Reinforcement and disinforcement are not forever ⇒ “extinction”, “reversion”

Partial reinforcement, which provides a random "reinforcer", is more resistant to extinction than continuous reinforcement, which provides a "reinforcer" every time

It's best to release reinforcers or aversive conditions as soon as possible, but no later than 60 seconds after the behavior in question

------------------------------------------------

In Practice

Think about how to best reinforce, and how to avoid disinforcement

The quickest way to create a “reinforcer” is to have a "goal" and clarify "what it takes to achieve the goal"

Dangling multiple subgoals against a larger goal makes it easier for various systems to function

It is also possible to consider a combination of continuous and partial reinforcement

Eliminate unnecessary stress components that could cause disinforcement

”Fun, even when you lose” is the ideal

On higher difficulty levels, make sure there is some kind of a “reinforcer” available in defeat

It's important to be able to see that you're making more progress than before when retrying

It's better to give the player a taste of what it's like to clear something difficult before making them try even harder things

------------------------------------------------

Special Edition

if you rank the reinforcements for each feature of your game to see whether they are working properly, it will help to highlight what you are missing

It's also good to simultaneously rank the various elements to also see if there is anything that could cause disinforcement

Note that if a type of “reinforcer” that worked in the early to middle stages of the game stops working in the later stages, there will be a decrease in motivation, often seen when players make it to the end and give up

It's also important to know how to keep the “reinforcers” alive and well until the game is over

That’s a lot of stuff... I wonder if anyone has even read this far? I’m starting to worry, actually.

What I've written in the "In Practice" section is just what I would do if I were to apply my knowledge of behavior analysis, so you can probably use it in other ways if you want to. Please let me know if you think you can actually apply this stuff to design a good game.

Alright then. I hope this stuff helps somehow. That’s it for the wrap-up. Now for the extra stuff.

------------------------------------------------

References

The information presented here is only the basic fundamentals of behavior analysis, so if you are interested in behavior analysis, please do feel free study up on it yourself. As long as you have the knowledge, the rest is up to how you use it.

By the way, the books I read to write this article are as follows (*Note: These titles are in Japanese and do not appear to have English translations, unfortunately):

------------------------------------------------

Koudou bunseki-gaku nyuumon: Hito no koudou no omoigakenai riyuu (Shueisha Shinsho)

This is a good introduction to behavior analysis. It explains the basics in an easy-to-understand manner.

------------------------------------------------

Merit no housoku koudou bunseki-gaku: Jissen-hen (Shueisha Shinsho)

This one is a little more advanced than the book above. It includes many references from actual clinical cases.

------------------------------------------------

For example, for partial reinforcement, there is research on "reinforcement schedules", which is about the proper timing to use for releasing a “reinforcer”, and whether different timing changes the properties of said reinforcer. If you're interested, this is good stuff to check out.

One last little problem (messing around)

Alright, we're done with the wrap-up, so allow me to pose one final question. What is the “reinforcer” motivating me to write about game design theory? Do you know?

oh yeah – you know... right?

.

.

.

That’s right! “Likes” and “Retweets” are a great way to show that you've written a good article and managed to help game designers. Of course, direct feedback also works as a “reinforcer” to the extent that it tends to get me super hyped up for hours on end.

By the way, you can get more impressions from "retweets" than from "likes", so "retweeting" is sometimes stronger as a type of “reinforcer”. And no – this is just an explanation; nothing personal, OK? Hahaha.

―――

So, did you find this article helpful?

If you're interested in checking out some games that take advantage of the "game design that makes you want to play even more" stuff described in this article, then I've got just the game for you. The Use of Life by Daraneko Games.

That’s right! Seeing as how the game was made by me – the writer of this article – it goes without saying that I put a lot of this stuff into the game.

The demo version is now available on Steam, so by all means go ahead and give it a try if you’re interested.

It’s a “game book-style” RPG in which the player-character’s various “attachments” change in accordance with the choices you make, with the story’s ending also changing ultimately depending on your “use of life”.

https://store.steampowered.com/app/1483370/

The Early Access version has been released. If you've played and enjoyed the demo, please be sure to check out the Early Access version, too!

Personally, I love seeing my games being added to more and more Wishlists, so if some of you readers out there were to go so far as to add The Use of Life to your Wishlists, that would be a nice little piece of the “goodness” for me.

I just might get motivated to write up some more of these game design articles.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like