Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Dreaming Spires: Dynamic Narrative, Layer by Layer 2

For our upcoming game Pendragon we've tied a dynamic narrative engine to a chess-like strategy game. Boards, moves, pieces... and combinatorial explosion. Here's how it works.

Pendragon is a narrative strategy game being made by inkle, the creators of 80 Days and Heaven's Vault.

Our last game, the IGF-winning Heaven’s Vault, was a 20+ hour adventure game that plays out differently for every player, and every time you play. It worked by combining a standard adventure game world with a highly contextual, dynamic dialogue system. The world provides the input - what do you find? In what order? - and the dialogue system spins it out into a narrative.

For our next game, Pendragon, we wanted to push that idea further. Is it possible to make the entire narrative out of contextual dialogue? Instead of tying the conversation engine to something rigid, like an adventure game world, we’ve tied it instead to a procedurally-generated Chess-like strategy game. Boards, moves, pieces... and combinatorial explosion.

Here’s how it works.

The Blueprint

Heaven’s Vault's dialogue system consists of an enormous bucket of short conversations, tagged with what discoveries make them relevant, and a system for deciding what to say next.

That system - which is driven by what the player finds in the world, and also what they talk about - is ultimately the thing responsible for delivering a coherent and engaging narrative across the game’s 20h running time.

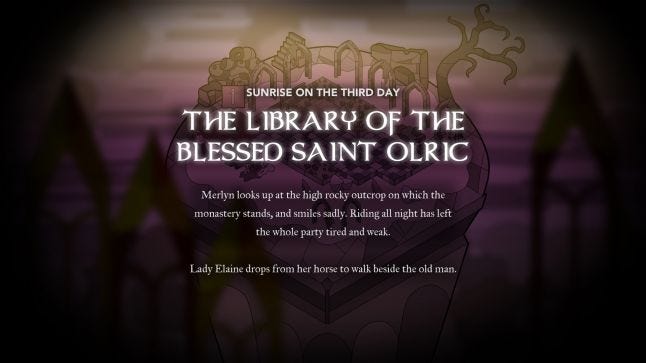

A game of Pendragon - which is roughly as long to play through as 80 Days - consists of a series of “boards”. Each board is created based on the required difficulty (which increases across the course of the game). It’s given a setting type (“weird forest”, “crumbling ruin”, “village”), and then populated with appropriate enemy pieces (“wolf”, “bear”, “rogue knight”, “blacksmith”) that the hero party then attempt to fight, sneak and talk their way past.

The system for the narrative is like Heaven’s Vault's: an enormous bucket of lines of dialogue, or lines of description, tagged with what’s required to make them fire. But it’s also quite a lot more structured too, with layers of content arranged from highly specific down to highly generic.

The Ground Floor: Responding to Game State

The basic tags are all tied to the gameplay. Who’s moving? What kind of move are they making? What consequences does the move have on the game state? Which other pieces are involved in this move?

We test these using a “play” condition which takes three parameters - a description of the piece doing the move, a description of the move, and a set of things the move and piece mustn’t be. Here are some examples:

play ( HEROES, ATTACK)

a hero piece is attacking someone

play ( HEROES, (ATTACK, EXCHANGE) )

a nervous hero piece is attacking someone, but is about to be captured in return

play_not ( (NERVOUS, HEROES), ( ATTACK, EXCHANGE), LAST_PIECE)

a nervous hero piece is attacking someone, is about to be captured in return, but isn’t the last piece on the hero team

Not every line has every kind of tag, and queries on tags can be highly specific - is Lancelot speaking, or Guinevere? - or they can be more general - Is the piece speaking someone confident, or someone nervous? Are they injured? Are they a knight, or a villager recruited to the cause?

Pendragon has a bank of about a thousand of these, arranged in rough priority order, with some additional tags to prevent close repetition of lines. These form the lowest level of the game’s thinking - the fallback content.

The Mezzanine: Responding to Game Setting

The next layer is similar to the previous, except it’s reserved for lines that reference the “skin” of a board more directly. This is done on a separate layer so it can be swapped in and out as required: there’s no point processing dialogue about villagers when you’re knee-deep in a snake-infested marsh.

This layer uses all the same tags as before, but are only active is other conditions are met about the setting, or the piece being attacked; things like:

play(HEROES, ATTACK) && is(victim(), BEAR) -

the knight slices through the bear

play(WOLF, RETREAT) && isLocation(FOREST)

​​ the wolf slinks a step back between the trees

Together these two layers give us playable locations, with a lot of colour:

Turn 1: LANCE advances

LANCE: There’s a wolf between the trees.

LANCE: I don’t think it’s seen me.

Turn 2: WOLF advances

WOLF: Grrrr…

Turn 3: LANCE holds position and draws his sword

LANCE: Steady now. Watch the eyes…

Turn 4: WOLF captures LANCE

The wolf leaps, and Lancelot is knocked to the floor.

GWEN: Lancelot! No!

But they still feel very much like barks; they lack the feeling of narrative because there’s no continuity from one moment to the next. In the example above, it’d be nice if Lancelot could, on Turn 3, curse and remark that the wolf has indeed seen him.

The Second Floor: What Just Happened?

The next layers of the stack introduce new ideas to move from describing the game state to creating a narrative around it, introducing ideas such as “did I just say X?” “Did I speak last?” “Is the piece I’m attacking the one that moved on the last enemy turn?” This allows you to set up simple chains of conversation, as follows:

Turn 1: LANCE advances

LANCE: There’s a wolf between the trees.

LANCE: I don’t think it’s seen me.

Turn 2: WOLF advances

WOLF: Grrrr…

GWEN: I think it’s seen you, Lancelot.

Turn 3: LANCE holds position and draws his sword

LANCE: I’m not afraid…

Turn 4: WOLF captures LANCE

The wolf leaps, and Lancelot is knocked to the floor.

GWEN: Lancelot! No!

GWEN: You might be brave, but why are you so stupid?

As with the tags for piece types, these “what did I say recently” queries can be quite generic; we aim to reuse content intelligently as much as possible and avoid writing entirely bespoke chains. The above sequence of moves - advance, advance, hold, capture - may only appear once in a hundred games, as the both the human and the AI player are free to make any valid move on their turn.

It’s important to find a balance between making triggers so specific they never fire, and so general they lose the sense of coherence.

The Third Floor: Dynamic Relationships

The next layer of our plot machine is reserved for dynamic plot: in-game events which are too significant not to be carried across the entire game. These are largely driven by relationships between characters.

For instance, at the start of the game, Guinevere loves Arthur and Lancelot, Arthur loves Guinevere and so does Lancelot. These relationships are turned into tags - Guinevere is conflicted, Arthur is betrayed, Lancelot is dishonourable (and no one is happy.)

The game then uses these tags to respond to events such as:

An unrequited lover saves the object of their affections, who thanks them awkwardly

A nasty, betrayed lover leaves their cheating partner to be killed

A nervous, conflicted character can’t choose between two people to help

These relationships are also allowed to change across the course of the game. When a lover dies, a character may become broken-hearted. An unrequited lover may earn the respect and even love of their beloved by saving their life. Equally, love may turn to hate and jealousy, setting up new relationships to be responded to by the game.

(Dynamic relations can then power gameplay effects: a character may obtain a devastating self-destructive move on the death of their lover, or a powerful burst of action on a declaration of unrequited love.)

The Rest of the Entire Building: Generating Plot

All of the above forms the basic core loop for Pendragon, but as you might expect, it becomes invisible very quickly: players begin to skim over it. It’s not the oatmeal problem - it’s easy enough to provide a huge variety of responses (short, long, funny, sad, etc) - but rather it becomes clear that the text is only ever an output and never an input, and so the player learns that reading is optional, and will soon or later stop doing this.

We first encountered this problem when developing Sorcery!'s combat: a Rock, Paper, Scissors-like simultaneous game, in which each round is converted into a procedurally assembled prose fight sequence as you play. We solved the irrelevance problem there by adding “tells” - the prose would include some text to suggest what the AI character was about to play on their next turn, so by reading it, you could make an informed guess about what to do next.

(We really liked this system too! But reading reviews there’s a clear gap between “people who saw we were doing it” and “people who still ignored the text and found the combat too random.” Next time in bold type, perhaps.)

But for Pendragon that kind of solution is too simple: we need plot-construction, to carry our band of knights from the edges of Britain all the way to Arthur’s side; we need world-building; and mysteries; and strange prophecies; and all the other things that combine to create a sense of mythology, character, and presence in the world.

Floors One Through Two Hundred: Scenes

Each “new board” is assigned a scene. Scenes can be generic and repeatable (“fight in a marsh”) or highly specific (“the wood where Merlyn went missing”). The scene then provides a top-level of dialogue barks, which are used before anything else is considered, and these can be very specific; setting up the level, discussing it; exploring it; while still handing control down to the lower levels.

A discussion of, say, what happened to Arthur’s fabled sword Excalibur, might be interrupted by a wolf mauling one of the main characters to death. Or it might proceed to its conclusion, with one character naming a monastery where the sword is rumoured to be held - which you can then travel to and visit, cueing another specific scene in which, perhaps, the sword will be found, if the stabby monks don’t get you first.

Conversations told this way are very fragile: they need to be interruptible, and be able to pick themselves up again if left half-finished; but this is a problem we already solved in Heaven’s Vault, and we’re employing the same knowledge tracking techniques we developed there.

The logic behind deciding what scene to play when is quite subtle! As with Heaven’s Vault, there is a game-wide “story manager” whose job is to ensure interesting things happen, but not too often!

The manager is aware across the wider game-loop as well, so a story that appears in a first play-through is less likely to reappear in the second if there’s other content to explore: a feature we were unable to put into Heaven’s Vault because of the fixed nature of the game world.

The Dream of Camelot!

And that’s the whole of the castle; from base foundations up to turret-rooms, banqueting halls and bedchambers. We’ve been throwing boulders at it for a while and it seems to be holding up!

The Steam page is up, the wish-lists are trickling in, and we should have a playable demo along very soon. Pendragon should be out in early summer!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like