Designing game play for escape rooms using video game design techniques

Designing game play for "real world" escape rooms using video game design techniques: building a narrative, puzzle design, level progression, and the integration of technology.

When I was asked to create horror-themed escape games for Fright Nights, I jumped at the chance. Fright Nights is an annual event with 4 haunts and a midway with rides, scare zones and concession vendors. The event attracts over 35,000 visitors during its 4 week run.

After years of designing video games, I had only recently left that industry and was working on more real-world designs in residential construction and haunted house design. With escape rooms, I saw the chance to combine my construction knowledge with my video game expertise to bring my virtual designs to life -- pretty much every gamers dream. So below, I will share with you how I designed escape rooms using my video game expertise.

Overview

Escape Games aka Escape Rooms, are location-based entertainment venues where people come together to play a game. The game play for these rooms can be compared puzzle-solving adventure games, where the player(s) are the protagonist in an interactive story, driven by exploration and puzzle-solving.

Before designing any game, you must first understand your audience – escape rooms are no exception. You need to know as much as possible about the people playing it, so you can tailor the game to suit their needs: age, gender, interests, type of games they play, income level, etc. This will help determine the content and genre of the game you create as well as the price point.

At Fright Nights, we knew our audience would be 18-24 on average, have an even gender split with weighted interest in horror. We also knew they would have very little disposable income, so to achieve a lower price point we would have to design a larger game to accommodate more players per hour.

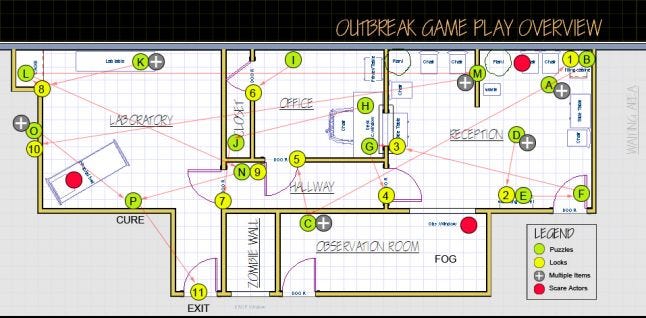

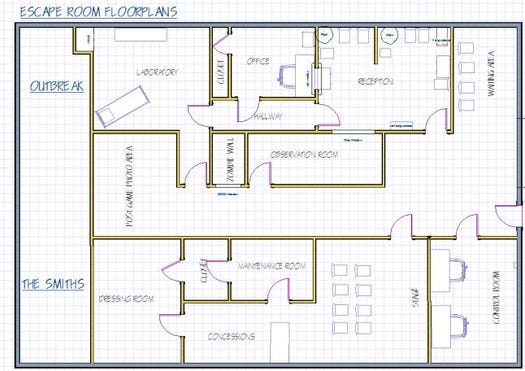

The rooms I designed were "Outbreak," a post apocalyptic zombie game and "The Smiths," a murder mystery with clowns.

Next, we set about playing as many escape rooms as possible to get a handle on our target audience’s expectations and also to size up the competition. Some were great, but more often than not, they were painful to play. My guess is novice EG designers do not understand basic game play mechanics that perhaps seasoned game designers take for granted. While it can be difficult to articulate what makes a game fun – it is VERY easy to define what makes a game bad. This applies to both escape rooms and video games. People want immersive game play that is entertaining and challenging. If you make them feel like they are in school, you will lose them fast.

What makes a game bad?

The story is boring or uninteresting

Lack of polish

Unclear goals

No tutorial

Puzzles are not integrated into the overall story or theme

There is no progression from easy to hard

Ineffective game moderators/game masters

No creativity or diversity in puzzles

Understanding Escape Game Mechanics: Puzzles, Boxes & Locks

Understanding the game mechanics of escape games is essential to designing a good experience. Technically, escape games are a series of locked items(which I will refer to generically as that require solving puzzles to unlock to move forward.

In the simplest terms: Find Locked Box -Solve Puzzle – Get Code – Unlock Box – REPEAT

Almost every puzzle, or some component of a puzzle, is locked up and the player must solve them in a certain order to progress. The exception is the first event – or “kick off” puzzle, which is typically just hidden and the answer to this puzzle will unlock your first box. Riddles and simple puzzles work well for this first event as they can be hidden in plain site.

It is important to note that if you have larger groups (8+ people) it is good to have some non-linear puzzles as well, that way you won’t have people standing around with nothing to do. Puzzles can either be simple or complex, and the more experience you have, the more complex you can make them. Always design easy, gratifying puzzles at the beginning of the game and save more complex puzzles for the end – this is a concept that will be discussed in depth later. Since puzzle solving is the basis for this genre, make them interesting and engaging.

Simple Puzzles

Simple Puzzles are typically those that can be solved without additional clues and are something the player will instantly recognize. They can be anything from actual puzzle pieces, to paper puzzles like Sudoku, riddles, crossword puzzles, anagrams, a rebus, mathematical puzzles, match stick puzzles, etc. Seriously, I can’t even list them all.

As I said, the kick off event is a good place to use one of these simple puzzles. Let’s say there is a book lying on a table. The inscription is a riddle, like:

“Some try to hide, some try to cheat. But time will show we always will meet. Try as you might to guess my name. I promise you’ll know when it’s you I claim.”

The answer is “DEATH”

Find a locked box with an alphabet lock on it, put in the word “DEATH” – and voila – you’ve opened your first box. The box itself could be a chest with a skull and crossbones painted on it to give the player an additional hint, depending on your story line. I prefer to move away from simple to more complex puzzles sooner rather than later.

Complex Puzzles

Complex puzzles require players to combine objects or clues to solve a puzzle, like a Cipher/Decryption puzzle. These require players to find both the code and a decryption key (legend) – then they must combine those clues to solve the puzzle. The best puzzles may not even be obvious; instead they are cleverly hidden within the narrative.

For example, let’s say the game involves solving a murder case on a news set. The player finds a video tape –circa 1989. When they play it, they watch a news reel that was filmed in the very room they are in, but something’s different. The objects on the wall behind the newscaster (e.g. frozen clocks) are now scattered throughout room.

The puzzle is the clock order. The decryption key is the news reel.

When players use the reel to put the clocks back in the correct order, the clocks provide the answer to your next locked box. Perhaps the time on each clock is a code, or the back of each clock has a number, etc. The news reel itself adds to the narrative, and the clues are integrated into the story.

Complex puzzles are only limited by your imagination – so anything goes. Just be prepared, because if you build some type of Rube Goldberg “Incredible machine,” your players will find some way to break it and/or try and take it apart in ways you have never even considered. So make sure your designs can withstand an insane amount of “man-handling. “

Boxes

OK, now you need a “box” – something to put these locks on – and the story is going to influence what you lock. “Boxes” can be anything – from an actual box, like a trunk or jewelry box – to doors and windows. The goal is to integrate these boxes into the sets and your story line.

If it’s pirate themed, you will probably want a locked treasure chest or a hidden door. If it’s a military bunker, then maybe some locked cabinets, desks or a wall safe. Players will appreciate your ingenuity if you integrate your locked object into your story. Almost anything can be made lockable if you add heavy duty hasps to it.Lost that filing cabinet key? Throw a hasp on it.

One word of caution on using boxes with integrated locks (i.e. wall safes, lock boxes, etc.) Players may break the key off in the lock or “lockout” an electronic lock by trying too many times. If they break the key off be ready to standby with another box to replace it. And in the case of electronic locks, be sure to print brief instructions and have them nearby (I make stickers). For example: After 3 tries safe is locked out for 30 seconds.

Locks

Physical locks require a code, pattern or key to unlock. The code/keys are usually hidden or revealed in solving the puzzles that are integrated into the game. From a game design perspective, physical locks are a bit limiting, so make sure there is a wide variety of types of locks and try to only use one type per room: keyed, alpha only, patterned, numbers only, colors, symbols, etc.

Using a variety of locks will also help your players solve the puzzles. If they see a lock that requires symbols to open it – they can begin looking for symbol based clues. It is also easier to design unique puzzles when you have different types of locks to choose from. You can get clever and provide items that act as keys like a fishing rod or stick with magnet at the end of the line, tools that can open things (Screwdriver, wrench, corkscrew)and even a magnifying glass that can make small text legible, etc.

There are are non-physical locks too – say a locked computer that needs a password to unlock, or a sequence of levers or buttons that need to be pressed in a certain order. These are advanced concepts that I will speak more about in the tech section.

PRO TIP: Make sure you buy at least 3 locks PER PUZZLE – and set them all up ahead of time. I cannot stress this enough: people will break or take the locks so have a few standing by. That goes for keys too – put them on GIGANTIC key rings and get lots of copies made.

Escape Game Hardware Tech

Using EG tech will keep your game interesting and set you apart from your competitors. Pneumatic and digital devices integrated into the environment are more interesting than physical (traditional) "lock on box" puzzles. There are many companies that sell finished puzzles or the parts that will allow you to make your own.

These are cool features, but they will cost you – in purchase, installation and maintenance. And like games, you have to prepare for defects. When an event such as “touch-this-painting-here-to-open-the-door puzzle” fails spectacularly, make sure your Game Masters are on point with a back up plan. Also, don’t use “tech for tech’s sake.” The puzzles should mesh with your story and not look completely out of place.

Advanced Tech: Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality is one of the hottest trends for smaller location-based entertainment venues. Although it has been used in (big budget) theme parks for years, the lower costs and easier access to the equipment have lowered the barrier to entry. VR naturally lends itself to escape games, as designers are not bound by the limitations of the real world. This serves up unlimited possibilities – from shoot outs with Aliens to interacting with ghosts – almost anything goes.

Like any integrated tech, however, you will now be required to have a more highly trained staff to support and maintain the users experience. There is also the added hardware costs. Many VR platforms are more than just the headsets. They have hand held devices / touch controllers for triggering and interacting with the virtual environment, room sensors, optic tracking, etc. and they are powered by a “beefy” behind the scenes computer.

Be advised, using a VR platform in a commercial entertainment environment that was intended for the consumer game market is most likely prohibited. In addition, hardware intended for consumer “at-home” use may not hold up to the rigors of high-traffic commercial use. This is important when you want your expensive VR devices covered under a commercial use warranty.

Fortunately, HTC began selling a business-focused version of its Vive virtual reality headset in 2016. Oculus followed suit and began selling a commercial VR bundle in October 2017.

There is so much more to VR than this article, but hopefully this gives you some sense as to what is involved.

Game Design

Getting Started

OK, now that you understand the fundamentals, it’s time to get started. Like a video game, before you can build your Escape Room, you probably need to determine how much it will cost first. Unfortunately, you can’t figure ANY of this out until you have determined the story and the scope of your project.

Oh, it’s a circuitous problem that can accurately be compared to sailing a ship while still building the hull. You’ll have to do some basic design work to get your initial scope and budget, and go from there.

One thing I will say about scope – the further away you get from a “modern day” theme – the more likely your project will cost. Themes like an office, a home or hospital, etc. will ultimately be less expensive to pull off than a period piece, like a castle, pirate ship or dungeon. These fantasy themes require more crafting and fabrication than those whose props can be purchased at a thrift store. The same goes for dressing your actors, modern day clothing and uniforms are easier to source than period costumes.

Building the Narrative

Every game designer has their own strategy, but this is where I like to start: telling a story. The narrative is going to influence the room/environment design, actor/characters (if any) and provide ideas for integrated puzzles and features. Like a video game – the story has a main goal, or quest. Escape games have a time limit, so you also need to build that into the story. This gives the story a sense of urgency and explains the game play mechanics in a narrative way.

For example: You are being held captive by a _______ (witch, serial killer, vampire, aliens, mad scientist) and you must escape before they return and _______ (kill you, you die, did I mention you’re going to die?)

So for demonstration purposes, I will choose a pirate theme and lay out a basic story and player goal: The player(s) are locked in Bluebeard’s cabin, on board the Pirate ship Revenge. If they don’t escape before he returns, the homicidal maniac will torture, kill and hang them on a hook in a room filled with the murdered corpses of his former wives. (Did I mention I prefer the horror genre?)

With this story in mind, I start by making lists of pirate themed stuff, torture themed items, and even fringe elements like his wives. I make my lists, but I put them into two categories: (1) BOXES things that can be opened/locked or contain a clue and (2) everything else. This would typically be 10x longer, but for the sake of brevity here are some basic lists:

BOXES

Treasure chest

Old wooden box

Parrot

Bottle of rum

Door to private cabin

Iron Maiden

Suitcases

Cabinet

Bar

Hourglass

Peg Leg

(2) EVERYTHING ELSE

Pirate slang / sayings

Pirate songs

Captains log

Spyglass

Globe

Treasure map

Whips, hooks or torture instruments

Ships wheel

Eye patch

Gold treasure/doubloons

Pirate art: skulls and crossbones, mermaids, etc.

Designing a game is not about any individual puzzle, it’s getting the puzzles to come together cohesively within your narrative. So this brainstorm session on boxes, locks & puzzles is essential in coming up with ideas that fit into the story and the overall game play goals. Notice I included things like parrots and peg legs on the “BOX” list – weird, right? Yes – but, like a box, they can “contain” a clue, as you will see shortly. I take this list and start brainstorming puzzle ideas, combining one idea from each column. For example:

The Pegleg could have a hidden compartment, with part of a treasure map rolled up inside. Find the other part of the map to solve the puzzle.

The hourglass could have a clue or code written inside it when the sand runs out – the clue would open a drawer that contains a spyglass

Players could use the spyglass to peep through a hole in the wall to read some otherwise small and unreadable text – the text could open a treasure chest.

Pirate slang could be written on a wooden box, and the player would have to fill in the blank to open the lock

Feed the parrot a cracker and it gives you a clue. Etc.

Now back to reality. From here I look at feasibility, like – can I really make a parrot talk? Probably not, unless I have the budget for animatronics. But how about that hollowed-out pegleg? OK, cool. As long as you can find or make one that doesn't look like a 5th grade art project, that’s a decent idea.

So I take the best ideas and try to put them in a sequence that reinforces the narrative. Another way to bring more story elements into the game is decor. The room itself can have items that build the story: a diary, photographs, a captain’s log, etc.

What about his ex wives? Maybe some clues to their deaths or some of their personal items, like diaries, etc. They do not necessarily have to be part of a puzzle. If you choose to have actors in the room, they can also contribute to the overall narrative. For example, the player unlocks a closet and finds one of Blackbeard’s wives alive – her narrative will add to the tale of the black-hearted Captain. These are all great ways to bring the story back into the game play and immerse the player. She may also give you a clue or a code – if you do something for her – like find her necklace.

This is also the point where you want to go and research Escape Game Tech – to see what – if anything, can be integrated into your theme. A hidden pneumatic door that is opened when the ships wheel is turned to a certain position, or when a book is removed from a bookshelf, etc. With VR you could be visited by the ghosts of Blackbeards dead wives.

Level Design & Progression

Like video games, design the puzzles so they get increasingly difficult, and each solved puzzle gives players more access or information. This is a universal concept in video games in which a character experiences some sort of progression that usually entails unlocking new abilities, skills, access to new items, or access to a new area of the game. Play testing (addressed at the end of this article) is the only way to know for sure if you have achieved this “leveling” goal.

Some early puzzles that I thought were super easy consistently took testers over 20 minutes to solve. So I had two choices, make it easier or move it to the end, (as long as the narrative allows it) because anything that takes that long right off the bat will lose your audience – in both the virtual and the real world. Play testing will also help you finesse your pacing. I think a good 1 hour Escape Room should have anywhere from 20-25 puzzles. The first set should be pretty easy to solve. The next set progressively harder and the final set mind boggling. Also, I prefer not make my puzzles completely linear to advance forward, which means several groups can be working independently of each other to solve different puzzles. This is particularly helpful of you have groups larger than 8 – if they don’t all have something to do, they will quickly become bored.

Paper Testing

Lay out your rooms on paper and play it like a table top board game. The equivalent in games is a proof of concept or first playable. It’s helpful to layout your room maps early on, even though they will change as you refine your game. Keep in mind how much space you have to work with and consider how many players you would like playing at one time as well. Don’t squeeze 10 people into a small 8’x8’ room. Video game players won’t complain, but I promise you real world people will leave snarky reviews on FB or YELP. Maps can be roughly sketched at first, then final layouts can be finessed on graph paper or in architectural design program for the final game design.

Intro/Outro Videos

Video games have intro movies and cut scenes – and so can escape rooms. Of course, you have to have the budget for that. This requires a script, actors, a set, video editing and the tech to display them. You can also buy "off the shelf" videos, but they will be more generic. These intro and outro videos can also be used as part of puzzles and to display things like a timer clock and/or hints.

The ER game Outbreak, that I designed, has good examples of intro and outro videos:

Audio

Part of what makes games immersive is the audio. Appropriate music and effects will go a long way in setting the tone of the game. Having the audio change as you play is also a way to make players feel progression. For example if you are in a post apocalyptic zombie game – players can start out hearing lounge music in an outer room, but as the game progresses and they get closer to the lab, they may start to hear zombies growling and banging.

Scoring

Consider a scoring system, especially if you intend to award prizes or post a leaderboard. Scoring could be as simple as best time. But personally I like to subtract points for hints, it gives more variation to scoring and provides incentive for players to work together. Anything more complicated than this will have to be tracked by the game masters, so make sure it’s fair and consistently enforced.

Leader Boards & Prizes

Consider whether you want to post game scores and give away prizes. Leader boards can be as simple as posting final scores on a Facebook page or investing in some software and creating an app that your players download. People love to share scores, so this could be considered a marketing tool as well. We took pictures of each group as they exited the escape rooms, and had them hold their time on a small white board. You can have automatic prizes for people who finish under a certain (impressive time) or you could enter everyone into a weekly drawing for a grand prize. Just be sure the rules are clear ahead of time.

Guest Experience

Be mindful of your guests overall experience. This includes before, during and after they play the game. BEFORE: If they have long waits in the waiting room, create a chalk board or have a TV playing something related to entertain them. Everyone hates waiting in line so it’s best to distract them and keep them busy. A photo-op is good too, and good for marketing as they tag and share. AFTER: Taking a group photo at the end of your game is a great way to help guests create a memory of their experience. You can have them hold their score or time finished for additional bragging rights. It is also a great time to get feedback, allow them to ask questions and collect any objects they may have put intheir pockets. I advise doing this outside of the Escape Room so your Game Master can reset while your guests decompress.

Legal

It’s a good idea to have an attorney review your rules & regs. Post rules, read rules to players and have the Terms & Conditions on your website tied to the ticket purchase. It is also a good time to let them know they will be video taped and/or photographed and that these images may be used in marketing promotions. Cover yourself in every way to reduce liability.

Documentation:

Game Design Document

Now you have the overall concept hammered out and your gameplay outlined - it’s time to put all your ideas into one structured document. In games, we call this the “Game Bible” or the Design Document aka the “GDD.” This is the document that contains all the information your team needs to build the game. The GDD will also help you refine your scope and overall production needs and be invaluable when it’s time to determine the budget.

Game Master Document

Each game needs a Game Master aka “GM”, and the GM needs their own set of instructions, post build. The GM monitors the game, enforces rules, gives puzzles hints, etc. The role is similar to a video game moderator, and they will follow the players progress throughout the game. The game master document will have the tools they need to help the players (hints, tips, etc) as well as a reset document so they can reset the room as quickly as possible.

Game Master Tips

Read the rules out loud! Yes – read the rules directly to all your patrons. They will still break them.

Have a reset list for your Game Masters to make room setup go fast. Schedule 15 minutes between games to account for room set up

Your Game Masters need walky –talkies to communicate with your guests, and a list of pre-written hints to help guests solve puzzles.

Be sure to ask all guests to empty pockets at the end – otherwise they will walk away with your stuff.

Have your Game Masters ready to replace a lock or improvise game play if something breaks, fails or disappears. Be sure backup locks are coded ahead of time and labeled in ziplock bags.

Place little stickers on the wall next to locks that have reset issues. For example, “Wall safe will lock you out after 3 incorrect tries. Please wait 3 minutes and try again.” Or “double click collar to reset lock.” You will find each lock has its own set of reset issues and instructions.

Scope, Budget, Build

Since this article is about game design, this section will be brief. The in and outs of building and escape game is a whole article unto itself. So here are the basics:

Scope

Now you have completed your GDD – you have your project scope.

Story

Game play

Game assets (locks, boxes, props, set pieces, furniture, etc.)

Game tech

Audio

Concept Art/ CAD Drawings

Videos (actors, filming, editing, display)

But there are more costs associated with escape games than the game itself, so next, determine your business requirements:

Global costs (insurance, space rental, business permits, etc.)

Construction expenses (walls, doors, floors, etc)

Technical support assets (cameras, walky-talkies, T.V.s lighting, air & sound, etc.)

Staffing for setup (game designer, carpenter, scenic painters, IT technicians, etc.)

Staffing for event (training, testing, Game Master, actors, greeter, ticket seller, etc.)

Marketing & Web (Website design, flyers, banners, etc.)

Scheduling and booking software

Actor costs (wardrobe, makeup, prosthetics, etc.

Inspections & permits (I’ve only included this because failing these can delay your launch)

Budget

With the game and business requirements together - you can finally run your budget numbers.

Build

You got your budget approved? Yeah! Time to build! Be sure to include a "control room" in your design. This is a location where game masters and the team can watch the players play the game without directly interfering.

Safety

Make sure your construction is solid, there are no sharp edges and avoid anything with glass if at all possible. Bolt everything down. Screw things to wall. Direct your players not to climb or “force” things. Some designers even go so far as to mark items with colored dots to show they are just a prop and not meant to be inspected. If you give players a tool to use, like a screw driver, don’t be surprised if they try to do something ridiculous like remove all the light switches or take the doors off the hinges.This is why you need game masters – to stop these types of shenanigans.

Your local fire marshal will also have something to say about safety, like all exits should be clearly marked and you will probably be required to have a fire extinguisher – another item that should be marked “not a prop.” In our case, we did not really “lock” people in – the final door was locked, but they could escape through several emergency exits at any time and we made sure they understood where all the exits were.

OK – you’re done? Awesome! Let’s get ready to launch this game!

Pre Launch

Marketing

If you haven't started marketing already - you better hop to it! Most successful launches are built on months worth of buzz and social media marketing! This would also be a good time to test your back-end Online ticketing software, if you haven't already, but I digress....

Play Testing

DO NOT SKIP THIS STEP! DO NOT SKIP THIS STEP! DO NOT SKIP THIS STEP!

In games we have multiple testing stages (Alpha, Beta, GMC, etc.) , so I suggest you do the same for your escape rooms. Get a group of friends to come in and kick the wheels. Even do one session where you ask people to try and cheat so your GMs can practice policing it. Play testing is a good time to train your Game Masters, as they need to understand you vision, inside and out. Test. Get everyone’s feedback, finesse the game, and test, test again!

Game Launch

Opening night! You have your control room set up and your first group is ready to enter the game! This is a very exciting time - because, like any live performance, anything can happen!

Be prepared to be up close and in person with your audience. If they don’t like it, you will hear about it. It’s one thing to read a review on line, it’s quite another to have someone in your face complaining about your game. You might consider what to do about angry players ahead of time – like giving them a discount, promotion codes or just plan to refund their money. Just make sure your game masters know how to handle this type of customer service event. Like all games, you will have to work out these kinks as you go along, so be prepared for the worst and hope for the best.

Final Tips

That’s it for now. In summary, I will leave you with some real world tips that I found helpful:

All Rooms will need to be monitored via cameras for several reasons, (1) people break things, (2) they cheat and (3) you will need to be able to give them tips and reinforce rules like “no climbing” or trying to wear the props. Also insurance companies like it, as it reduces liability should someone get injured doing something they are not supposed to be doing.

Lock up phones: Some ER’s use lockers and have people put away their phones – you don’t want them giving others cheats into your games.

Trolls. Some people can ruin the game for others, so my preference is to have people book rooms as a team. The most complaints we had is when we put strangers together in a room and they were just not compatible personalities. Leeeeeroooooooy Jenkins!!!!!

Place little stickers on the wall next to locks that have reset issues. For example, “Wall safe will lock you out after 3 incorrect tries. Please wait 3 minutes and try again.” Or “double click collar to reset lock.” You will find each lock has its own set of reset issues and instructions.

Laminate your paper clues (riddles, puzzles, etc) as they will get destroyed.

Writing material: give your players a pencil and paper so they can solve puzzles. I prefer a small whiteboard and dry erase pen.

Extra batteries for any items that require power like flashlights or black light flashlights.

DUPLICATES! I cannot stress this enough. Have duplicate puzzles and locks ready to go. At least 3 of each. With basic wear and tear plus you will go through them all in the course of a month!!!

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like