Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

I think the Theme vs. Mechanics discussion is fallacious. I believe it’s missing an incredibly important third piece that changes the relationship between the two: Feeling.

A few months ago I listened to an episode of The Game Design Roundtable that focused on the theme vs. mechanics debate. I recommend listening to it as I’ll reference it a decent amount below. I’ve been thinking about the discussion and trying to put my finger on why it continues to bother me.

Here’s the problem: I think the Theme vs. Mechanics discussion is fallacious. I believe it’s missing an incredibly important third piece that changes the relationship between the two: Feeling.

I strongly believe that a game designer’s primary goal should be to provide the player with a very specific feeling. The other two parts are important, but ultimately exist to create this feeling. Other media accomplishes this through theme alone, but interactive experiences such as games have the unique ability to lean on both mechanics and theme to provide a much deeper connection to the feeling.

Theme, Mechanics and Everything

The debate isn’t new; googling it presents dozens of articles and podcasts discussing the constant struggle to balance the two to provide an optimum game experience (ludonarrative dissonance, if you’re into that).

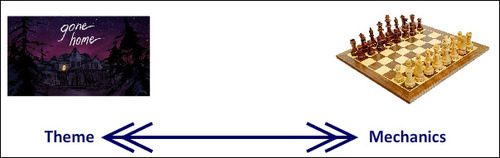

Differing amounts of the two parts. Both good, they just offer a very a different feeling.

Other articles identify it as more of a sliding scale, with Purely Mechanical at one end, and Purely Thematic at the other, pointing out that the slider doesn’t have to be at the 50% mark to make a good game.

It’s clear to see why a game emphasizes mechanics or theme: One allows the player agency and slowly builds emotional investment in the game; the other gives the mechanics context; making the agency interesting and complex.

Mark Rosewater, Head Designer for Magic: the Gathering notes that familiar themes help the player compartmentalize the interplay between mechanics. The specific mechanics of the Frozen Solid card imply that the creature cannot move and that the lightest touch will shatter it to pieces, killing it. The mechanics completely support the theme of the card.

The mechanics and theme blend together to evoke the feeling of freezing a creature.

Keep in mind that familiar themes bring connotations along with them. Using a very defined theme sets expectations for specific mechanics to be a part of the game. A space game that doesn’t involve traveling to planets in a spacecraft for example, might disappoint players.

Even in games like Chess that are almost purely Mechanical, the theme of rival armies going to war helps provide context for the mechanics. The pieces are named for military units, and capturing or killing the rival King ends the battle. It just makes sense.

The discussion of the two aspects of game design at opposite ends of a spectrum is familiar territory, but it’s important to recap before I introduce a new piece.

What is this feeling?

So let’s get the First Big Caveat out of the way: When I use the term “feeling”, I don’t mean the feeling of having fun. Fun is a much more complex topic to wrangle, and one that has a fair amount already written on it. The two concepts are definitely connected: a strong and focused feeling can provide a lot of fun. As I’ll touch on later however, strong feeling isn’t a guarantee of a fun experience.

"Feeling" is the very specific emotional connection the player has to the game experience and the player’s place within that experience. A game’s feeling is always supported by the relationship of its theme and mechanics.

Theme and mechanics work to support feeling, not each other.

The feeling of a game is defies any single objective definition, but it’s essential for a strong design. Every design begins with the goal of evoking a specific feeling from the player. A game uses both theme and mechanics to evoke that feeling.

A few examples include:

I want to make a game where the player struggles to keep an empire alive.(Pandemic, The Civilization Series)

I want to make a game where players feel suspicious of their allies at every turn. (Battlestar Galactica: The Board Game, The Resistance)

I want to make a game where the player feels alone and is forced to rely on his or her own wits to make progress. (Myst, Another World)

By starting with the feeling you want the player to have, you force the very next question to be “How will I accomplish this?” You get right to the core of what I believe game design to be: deciding what tools from your theme and mechanics toolbox you’re going to use to achieve that specific feeling.

Let’s examine Battlestar Galactica: The Board Game. In the game, players attempt to survive aboard their ship, battling enemies and trying to keep their ship properly duct-taped together. However, there's at least one Cylon traitor aboard secretly attempting to undermine the efforts of their teammates without being caught.

I don’t need a game like this to inform me which of my friends are utter jerks, but it helps.

The hosts of The Game Design Roundtable podcast correctly identify that the traitor mechanic has been around for a long while, but that makes perfect sense to be used here. It’s a natural inclusion in a game based on a television show that revolves around constant suspicion of who the next traitor will be. The mechanics (The Traitor being a large one) combine with the theme (space battles, a ship constantly in danger of breaking apart) to create the specific feeling the game designers wanted: that of being one of the characters on the show, constantly questioning relationships and desperately clinging to survival.

To me, game design is a kind of behavioral psychology. It’s about observing and making sense of human expression and interpretation. It’s the reason I love games; they are a way for me to more deeply understand what it means to be human, and how we all connect with each other. Focusing my own designs on creating a strong feeling for the player is the natural extension of this.

Mechanics, Dynamics and Aesthetics

If this all sounds familiar, you might have read the fantastic paper on the MDA approach to game design. The authors of the paper, Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc and Robert Zubek describe a unique framework for understanding the differing perspectives between game designers and game players.

The MDA framework shows that most often, the designer perspective of a game is one of Mechanics > Dynamics > Aesthetics, and player perspective is one of Aesthetics > Dynamics > Mechanics.

Aesthetics set the tone and feel of a game.

Dynamics create the specific, thematic examples of game affecting the player.

Mechanics are the rules affecting the player as well as the player’s agency in the game.

Aesthetics: Terror. Dynamics: Fear of the dark, fear of the unknown, etc. Mechanics: Monsters in the dark.

If you look at the definitions of the framework, you might recognize that Dynamics translates to theme, Mechanics translates to the same, and Aesthetics is that strangely hidden third piece: feeling. The opportunity to design from Aesthetics first translates perfectly to my theory that theme (Dynamics) and mechanics should be subservient to the end goal of a satisfying feeling, and that feeling should be a regular part of the theme vs. mechanics conversation.

(Keep feeling) Fascination

Creating a strong and enjoyable feeling is not an easy thing, but it’s the most vital part of creating a memorable game experience.

Co-host of The Game Design Roundtable podcast, Dirk Knemeyer, mentions that as in his early days of designing games, any time a mechanic would interfere with the purity of the theme in his games, he would squash it, even to the detriment of the overall fun of the game. While I agree that the two do need to be in concert to provide a strong feeling, the more you prioritize theme or mechanics over feeling, the more the feeling becomes harder to embrace emotionally. If mechanics are too abstract, they lose efficacy in supporting the theme. It becomes much less likely the player will, for example, feel like a wealthy Baron, taxing his peasants and sending them to work in the fields. If the theme is too abstract, the context added to the mechanics may confuse the player instead of providing insight.

When the game is over, the feeling of the game is all the player is left with. It’s what players remember most and will evangelize to others. The feeling of defeating the enemy army in a game of Chess, the feeling of using a far superior enemy’s tools against them in XCOM: Enemy Unknown, the feeling of being completely befuddled, not knowing where the game begins and ends while playing The Stanley Parable.

100% feeling

There are as many examples of why a strong feeling is important as there are good games out there. A strong, focused feeling begins the player down the path of immersion. It kick-starts the state of flow that we as designers work to provide to the player.

When I’m trying my best to survive hordes of demons with nothing but a shotgun in Doom, I AM Doomguy. When I’m faced with the possibility of losing loved ones because I made a snap decision in The Walking Dead: The Game, I AM Lee Everett. When I equip a group of men and women with the best weapons human science can offer and send them off to die in XCOM: Enemy Unknown, I AM the Commander. I am Kaitlin Greenbriar inGone Home and I am the faceless soldier in Battlefield.

I understand my place in the experience, and in that moment, when I connect emotionally with the experience of my avatar, it becomes my own.

More than a feeling

Here’s the Second Big Caveat: A strong feeling doesn’t necessarily mean a fun experience. Monopoly is my go-to example. When you play and succeed, you really do feel like you own a monopoly, but that in and of itself isn’t very fun. The feeling is strong and focused, but it’s not one a player necessarily WANTS to emotionally connect with.

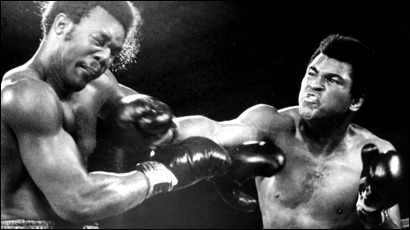

Another example: Co-host of The Game Design Roundtable podcast David Heron suggests a hypothetical trick-taking card game themed around Boxing.

Great feeling for the puncher, crummy feeling for the punchee and horridly broken game for both.

He theorizes that because boxing itself has a positive feedback loop (the boxer who successfully strikes a blow first will do better and better over time) any game with mechanics that seek to accurately model the sport will also suffer from the same loop, and the game will end up entirely one sided and un-fun for the loser. Even when mechanics and theme are working in sync to create a strong feeling, it isn’t a guarantee of a fun experience.

It’s all that matters

Feeling is, I believe, the reason we design interactive experiences. To this end, it’s only fair to re-prioritize the way we think about theme and mechanics to place feeling at the pinnacle.

Theme and mechanics are our tools to craft unforgettable experiences for the player. When the player understands their place within a game experience, we have the opportunity to reveal to them more about themselves, and their place within humanity.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like