Game as a Service: launch models and monetization approaches

An article about launch models, distribution, and a number of approaches to monetization for Game as a Service. Also some recommendations for successful project management.

For the past couple of years Game as a Service has started to become more and more of a popular business model. Its main feature is a steady return of investment, not momentary surges. Usually it’s the case with free-to-play projects, but GaaS is not limited to such games, it’s way broader.

In this article I’ll tell you about what kinds of GaaS there are, how they monetize, and how they’re distributed. I’ll also share with you some fundamentals of working with this model that you definitely should take into consideration.

I do have to point out though that these recommendations are not universal. Now that it’s out of the way, let’s begin.

Let’s narrow down to the three main launch and distribution models:

F2P.

P2P + DLC.

Subscription.

Now I’ll talk about each one in detail.

F2P

This is the most widespread model for mobile launches. The player plays the game for free but can pay for character improvements, temporary boosts for a level or a session, shorten ability use timers, etc.

For such games you have to consider a fundamental set of basic things they just can’t work properly without.

The right launch and distribution model.

Community management and support.

Regular updates.

In-game economy based on fundamental principles.

A set of start-of-the-game features.

This model is so popular because it makes the beginning of the marketing funnel the broadest and allows to buy installs more effectively.

A GaaS marketing funnel. In P2P projects a fewer amount of users will reach the “Let Them Play” stage.

The main approaches to F2P monetization are:

Selling power.

Selling vanity content.

Selling boosters.

Selling season passes.

The most reliable and trustworthy approach is selling power, where the paying players get instant gratification from their purchases. However, it’s hard to apply it to skill-based games with esports ambition.

Selling vanity content suits your game if you want to base the core game on brutal honesty and player’s skill — or you want to take Twitch by storm and gather huge arenas. The player can buy skins, animations, and other visual content that doesn’t have any effect on the player’s gameplay effectiveness. Fortnite is a prominent example of this approach. But, coming from my personal observation, 9 out of 10 games that chose this model ended up showing poor financial results and, eventually, shutting down. One of the main reasons for that is low ARPU caused by the game having nothing to offer besides vanity content.

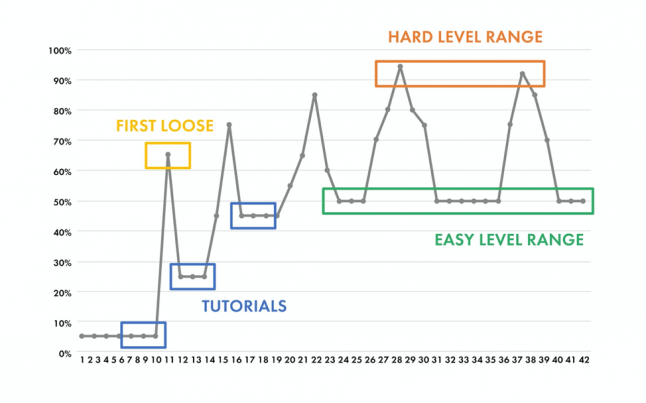

A popular approach in casual titles, especially match-3 games, is selling boosters. A booster is an expendable item that gives a temporary improvement to the gaming session. Think a bomb exploding nearby gems, a sledgehammer to break an obstacle, etc. This approach works well for casual games because of the logic behind these games. The players don’t mind a little help on hard levels.

Level difficulty distribution in match-3 games

It definitely doesn’t work for online games, especially for PvP. Sometimes, though very rarely, it can be seen in co-op PvE games.

Season passes are the trendiest model in 2018-2019. It can be a season pass, seasonal subscription, or a battle pass unlocking access to in-game achievements. The player doesn’t get gratification for the purchase — they still have to earn their content. The overall value of the prizes included in the season pass is way higher than its cost. Frankly speaking, I think it’s kind of a remodelling of daily quests in older games.

Selling season passes is a great additional approach to monetization. It doesn’t exist separately from aforementioned selling power, vanity content, or boosters, since it’s a means of content distribution, not a type of content itself. If this approach works and the players love the content and the challenges to get it — it’s a win-win for both the players and the developers.

NB. You can use all three approaches in one game further in developing and managing the project. Guns of Boom, World of Warships Mobile and PixelGun are great examples of doing just that.

P2P + DLC

One of the hardest, most risky distribution models. There’s a couple of reasons for that:

Large launch marketing costs.

Competition with the market’s biggest sharks (EA, Ubisoft, Blizzard).

Release date limitations to avoid competing for players’ attention.

Longer game/DLC production cycle.

Larger teams and production costs (we’re excluding the indie devs now).

However, this model has pros as well:

Faster return of investment in case of successful launch.

Less reliance on metrics (retention, NPU conversion, etc.) in management since the player pays for the game itself and further purchases are but an extra type of monetization. GTA Online and Destiny 2 are notable exceptions that make a lot with in-app sales.

A wide choice of distribution platforms (Steam, Epic Games Store, GOG, etc.).

This model is stable at PC and console gaming markets, but hasn’t really stayed at mobile markets. Its main principle is selling the game at full price with all the content, that is supposed to be played over 6-12 months of occasional gaming. These games don’t usually have any progress boosters. As soon as most players run out of “vanilla” content, DLCs come to the stage with a new serving. This will happen several times before the player interest decreases and the developer will stop supporting the game.

For the past 2-3 years developers have started integrating more in-app purchases into P2P games, both single- and multiplayer (i.e. Assassin's Creed Odyssey or The Division 2). Rainbow Six Siege has gathered many monetization approaches together: they have season passes (+ battle passes coming soon), vanity content, and boosters that allow you to temporarily receive more coins. If the game is built for P2P model it still can use some of the F2P monetization tools.

Service subscription

PS Plus, Xbox Game Pass, and EA Access have been with us for a while, and now more and more big players are entering the service market: Ubisoft presented Uplay Plus at E3 2019, and Apple will launch Apple Arcade in fall. The principle here is easy: the player buys a subscription and can access a library of games by selected publishers. They can still buy the games separately.

The most interesting type of service subscription now is cloud streaming. It has existed for quite a long time (Onlive, Gaikai, PS Now, etc.), but hasn’t become that popular yet due to the connection speed and quality and the current state of technology.

But it all can change in November when Google Stadia comes out. The user will still have to pay a monthly fee and receive access to a game library. The difference here is that the games will be ready to play on every device running Google Chrome. It is known now that besides Stadia Pro subscription this platform will host other publisher’s subscriptions, as well as sell games separately.

We still don’t understand how much and by what principles the developers are paid if they choose to distribute their games on such platforms. Maybe in the future this will change the fundamentals of game design, but now is too early to make assumptions.

Working using a GaaS model

Let’s talk about the important features of making a GaaS you should consider right when you start your project. I’ll use War Robots as an example, but the same will stand true for PC and console games.

Regular updates

You have to retain players in your game and keep them interested. For that, you’ll need regular releases. The perfect timing for making updates (excluding hot fixes) is once in 3-5 weeks. In planned releases you should include new content, entertaining events (such as Halloween), and, in PvP games, you should re-balance from time to time.

Don’t update too frequently, or you may end up losing players, patch in patch out: some people won’t download the update, some people don’t have enough storage on their devices, etc. But don’t abandon the players for 2 months and more either. Try to find balance.

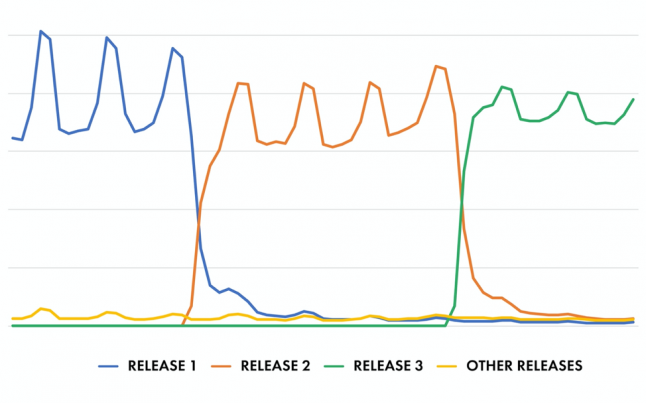

DAU behaviour in releases

I have to say though that we’re talking about user/content releases, not technical updates and fixes. The players have to receive something of value to themselves.

Player support

Quality player support is vitally important for GaaS. Even at soft launch stage it’s possible to enlist support managers to process user complaints and feedback. When you’re launching, try to pay personal attention to a maximum amount of users. Answer each comment and each ticket, no matter the type of a player.

Over time your project will get more complicated, and your audience will get bigger. The number of inquiries will increase, and you will be lacking resources. In that case you can turn to outsourcing support, but, frankly, it’s not the best option.

Segmenting the users is the right solution here. Divide the players by a number of criteria and script the interaction logic. I.e. paying users should have the top priority, long-time users who haven’t paid in a while are the second best, etc. Don’t shy away from using bots for automated replies — they decrease the strain put on customer support significantly.

NB. Don’t use the bots when you’re just launching. Keep them up your sleeve until you can’t manage the tickets with humans. But leave the top priority queues to the human managers.

If the project is in a soft launch or a closed beta stage, don’t plan for long ahead. Your roadmap may change every week, and that’s completely normal. Pay close attention to player feedback — it’s crucially important, and is way more vital than having long term development plans.

Community management

The longer a game exists, the more important its community and community management gets. Hire community managers at the soft launch stage. The way you run your social media pages, inform the users, and keep your promises will have huge impact in the long run. Over time it will become harder to buy traffic and easier to return a user to the game. Develop your reactivation points right from the start. Remember that your game’s viral potential is in the hands of the most socially active players. They can do everything themselves with a little help from you.

Don’t forget about feedback. There were cases when the developers lost a promising project because they kept silent about the game’s problems (Sea of Thieves, Fallout 76). There are also other cases, such as PUBG and Dota Auto Chess, where an unfinished game was warmly received by the players. It was possible because of the developer feedback: writing reports on social media and Reddit, answering the questions on Twitter, recording the developer video diaries. All of it has a positive influence on the player-developer relationship.

Another moment that some developers overlook is that the players speak different languages, some of which may be so complicated that it’s a real challenge to find a decent translator. For starters, localize your game in widespread languages (English, Spanish, and German) to have a foundation for a quick start and buying traffic. Then add Chinese, Japanese, and other more complicated languages. The list of required languages may change depending on your strategy and product features. For example, if you’re launching a social casino game, you definitely need Arabic right when you launch.

You don’t need many localizations to soft launch. Don’t overspend, choose a region to launch at and translate the game into one language. Usually it’s either English or Spanish.

Buying traffic

If you think you can avoid buying traffic and your game will become popular solely by its viral potential, I’ll disappoint you. Viral examples, such as Flappy Bird, that got really popular without any marketing are exceptions. Not very wise to rely on exceptions when you’re running a business, isn’t it?

Here’s the reality of the situation: you should buy traffic every year your game is being managed and developed (except the last one, maybe). Annually, average eCPI increases by 15-20%, and your game is getting older and older at the same time. Simultaneously, you have to work on increasing LTV and lowering CPI.

Here’s what can help you increase your overall ROI (return on investment):

constantly looking for new markets (countries, platforms, etc.);

launching worldwide campaigns;

integrating video ads and counting them in the traffic ROI;

platform featuring;

Influencer marketing;

constant work on marketing creatives;

ASO optimization;

launching on other platforms (i.e. making a Steam version of a mobile game).

And those are not even the most of the means of buying traffic more effectively.

Team size

A successful product is a complicated machine to manage. The more complicated the machine, the more expertise it needs to be supported. The number of your employees will increase in all departments. That’s simply inevitable.

Think ahead about how you’ll manage a big team. Send your managers to attend a management education program, or hire more managers when you see that your project has started growing rapidly. Usually, after a surge in growth, workflow gets chaotic, and you goal is to fix that.

When your team grows, effectiveness per employee reduces. 20 people don’t do twice the work of 10 people. Sometimes to solve a problem you don’t need an extra team member, but you do need to optimize the workflow.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like