Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

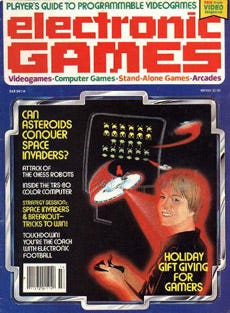

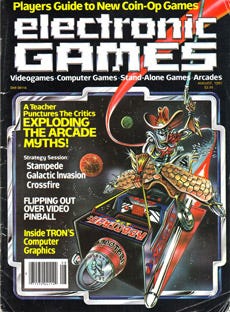

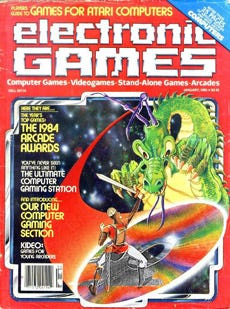

In this in-depth interview, Gamasutra sits down with Arnie Katz, the co-creator in 1981 of Electronic Games magazine, the first ever magazine dedicated entirely to video games, to discuss his history in the biz and the state of game journalism today.

Arnie Katz was a pioneer of video game journalism. In the late 1970s he, along with Bill Kunkel, started Arcade Alley in Video Magazine, the first column about video games in a major publication. Then, in 1981, Katz -- along with his wife Joyce Worley and Kunkel -- started Electronic Games magazine, the first ever magazine dedicated entirely to video games.

Inside the pages of Electronic Games, Katz, Kunkel [also interviewed by Gamasutra in recent years], and Worley invented video game journalism. The format of the magazine, letters, reviews, previews, features and many other types of content, while frequently borrowed from established traditions of magazine publishing, were molded to the subject of video games for the first time.

Arnie Katz was the editor of Electronic Games, and many fans saw the world of Golden Age video games through the eye of his editorials, which began each issue of Electronic Games. Words such as "playfield", "shoot-em-up" and many others entered the lexicon of video game fans after being invented or popularized in the pages of Electronic Games Magazine.

While there were other sources, at no other time in the history of video games has a single fountain of ideas and knowledge like Electronic Games led the charge in hearts of minds of so many people.

After Electronic Games ended in 1985, Katz, Kunkel, and Worley continued as consultants to the video game industry, and worked on later publications such as Video Games & Computer Entertainment and the '90s revival of Electronic Games.

By the 21st century, however, the pioneering mind of Arnie Katz had left the video game world completely. His partner, Bill Kunkel, has continued to consult for game companies, teach game design classes, and write about new and old games on the internet. He also wrote a book, Confessions of the Game Doctor, which is required reading for anyone who fancies themselves a student of video game history.

However, Arnie Katz -- ostensibly the inventor of the medium of video game criticism -- has remained relatively quiet in the same time. Gamasutra caught-up with him a few months ago, and he agreed to talk about the past, present, and future of the video game industry.

I have not read very many interviews with you in the past. I'm wondering if you shied away from it, or if people have not approached you... or have I just missed them?

Arnie Katz: It's a little of both. I've had so many good things happen to me in my life, I think it's a little vain of me to go out and say "you should interview me, because I'm hot shit." I know I'm hot shit. No, seriously, I like being interviewed, because I enjoy interviewing people.

Have you read Bill Kunkel's book?

AK: I've read some parts and skimmed others. I lived a lot of it with Bill. I'm sure Bill remembers it his way. We are still very good friends.

Bill includes you in most everything he wrote about.

Bill includes you in most everything he wrote about.

AK: Joyce, Bill, and I -- and Bill's then-wife Charlene -- were all very good friends. We met through science fiction fandom. I met my wife through science fiction fandom. After Joyce and I got together, we heard from this couple in Queens that wanted to come over and get to know us.

One night, they wanted to visit relatives in Chicago, and we all went into the city. We'd gone to see them off, and after we saw them off we went to one of the Times Square arcades. We were playing Pong, a new game at the time.

After a little while, Bill and Charlene walked in! Something had gone wrong with their train, and they were not going to Chicago. They wanted to play Pong, too. This was the first time we realized that we shared that interest.

Through the '70s, we played the various home games and went to the arcades. In 1978, a couple of things happened. One was, Atari and Magnavox put out programmable machines. There had been a couple of attempts to do such devices. One was the Fairchild, which was terrible...

Those plunger controllers...

AK: Yeah, you just could not play it. The other was the Bally Arcade, which was priced at about $400 at the time. It had very bad distribution and no third-party games. It was not really that attractive.

When the 2600 and the Odyssey 2 came out, that was a new era. At just about the same time, a guy a I worked with -- a fellow staff editor on a trade magazine I worked on -- got a job with Reese Communications to start a new magazine named Video. I pitched the editor, Bruce Apar, two different columns. I did a column about television and a column named Arcade Alley on behalf of Bill and I. The idea was to write it together.

Did you write it together?

AK: Oh yeah, absolutely. Bill was in every way my partner on Arcade Alley, on the magazine, along with Joyce Worley-Katz. I was, let us say, somewhat more advanced as an editor and writer when the opportunity came, but that does not mean that Bill did not do his full share, because he certainly did. We would sit around and swap ideas. Bill was somebody who came over to our house three times or more a week.

Was that all through the writing of Electronic Games and afterward?

AK: Oh, before, during and afterward. Bill and I are still friends. Unfortunately for me, Bill now lives in lovely Michigan instead of Las Vegas. He moved to Michigan with his wife two years ago. Joyce, Bill and I moved out to Las Vegas together. We decided we no longer had to live in New York, and we all moved out to Vegas. Until Bill's Michigan move, we lived about a mile from each other.

You guys wrote Arcade Alley for a couple years, right?

AK: Yes, Bruce Apar accepted both columns. The column about television was something I wrote on my own, and the Arcade Alley column Bill and I wrote together.

Frankly, the biggest problem we had writing that column at first was there were not enough games. We had to review every single game that Atari made because that was all there were. If Atari did not put out enough games... We aimed to have three games per column. We didn't always achieve that.

In '78 and '79 Atari maybe put out a dozen of games a year. In '79 they even held back.

AK: I know, it was amazing. When third-party publishing came in, there was nobody happier than Bill and I.

Who was Frank Laney II -- the original editor of EG?

AK: I was working as an editor and writer for a magazine called Chain Store Age and I wanted to keep my writing in the trade magazines separate from writing in the gaming world. I also did not want to have a discussion with my 9 to 5 employers about what I might be doing in my off hours.

So you weren't working for Reese Publications at the time?

AK: We were working on spec.

Was this for the winter 1981 edition of Electronic Games?

AK: Yes. Bill would go in there and work with the art people and so forth. I probably wrote a fair amount of the issue. I was the editor and associate publisher. My job was, in essence, to design and edit the magazine as well as write for it.

Fortunately I had Joyce and Bill to come up with lots of great ideas and shoot down my bad ideas, and occasionally tell me I got something right. It came to the point where I had to decide whether or not to stick with my day job.

When was that?

AK: I believe was shortly after the first issue came out.

Any regrets on your decision to leave Chain Store Age?

AK: Oh no. We had also (Bill Joyce and I), before Electronic Games, had done a pro wrestling magazine. It was mimeographed in our apartment, and gradually we got it sold in all the concessions stands on the East Coast.

That was back in the pre-golden age of my youth.

AK: Yes, the pre-golden age in the '70s, when it was still the WWWF (not WWF or WWE) and only in the Northeast. What we came up with was that our coverage was 95 percent on the East Coast. The magazine was going great guns, and it reached the point where we would have had to take the next step, which was to bring it onto the newsstand... and we had distributers lined up.

I would have had to quit my day job to continue it, but Bill, Joyce and I decided that we could not rely on the managers of WWWF to deal with us in a fair manner, so we had to walk away from the wrestling. In 1981 I came up against it again with Electronic Games -- should I go for it, or stay with the trade magazine? I called Jay Rosenfield, the publisher of Reese Communications and I told him exactly what the story was: I needed to walk away from Electronic Games or I needed a job. He told me to report on Monday.

Do you have every issue of the original Electronic Games?

AK: Yes, I do.

Have you ever considered some kind of compendium or compilation of your own writing?

AK: Well, most of it seems very ephemeral. I've considered writing a book, but I don't want to do my memoirs -- not my gaming memoirs, anyway.

Don't take that the wrong way. I'm saying Bill shouldn't have. Bill did a very good job, and the parts I read were excellent. I've at least skimmed the whole book and it seemed okay. I understand that everybody remembers things in their own way, and those are honest subjective memories.

I do think that your editorials in Electronic Games, when read in context, are fairly fascinating and insightful account of the rise and fall of the golden age of video games.

AK: Well, thank you very much for saying that. I did put a lot of work into the editorial. One of our aims with Electronic Games was to write for the full spectrum of our readers. The way we thought to do that was to aim high. We were aiming for adults, but also so that a smart teenager would be able to read it. If you were 12 and bright, you could read it.

I think it is very important to not condescend to the readers. I have great respect for the people that read Electronic Games magazine, and all the other things we did, like the video games section in VG&CE. We were not aiming at the 10 year old, but we were not excluding anybody. We kept the magazine clean. We did not try to have any risqué material.

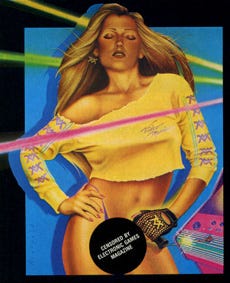

I recall in the original EG, a Private School movie advertisement that had Phoebe Cates' lower half blocked-out with a censor bar.

I recall in the original EG, a Private School movie advertisement that had Phoebe Cates' lower half blocked-out with a censor bar.

AK: When the art department got the graphic it was a little beyond our standards.

I was a bit upset by that as a teenager, but at the same time it was great because my mom could look a the magazine and not think it was something I shouldn't be reading.

AK: We understood. Bill and I in particular had been comic book readers as young kids and had our parents wonder, "Why are you reading that stuff?" All three of us had been science fiction readers, and to be a science fiction reader in the '0s and even the early '60s was to be weird; you were a pariah. Reading at all meant you were weird!

Anyway, we understood that sometimes kids had parental pressures and beyond that we wanted the magazine to be comfortable. You know, we wanted the language and visuals to be something that everybody would be comfortable with. We were sent a copy of Tilt magazine at one time, which was from France and began life as the French version of EG. This thing looked like the all-star Sex issue!

Well, you know Europeans and their magazines...

AK: Well, I'm not saying it's wrong. I'm totally against any form of censorship, so it did not bother me at all, but I know we would not have published a cartoon of a group of young women in a "circle", yet there it was. The issue had nudity and all kinds of things and it was certainly remarkable that they did that in France at the time, but it would have never flown here.

No way.

AK: Sex and video games have an uneasy alliance in that there are so many young male players, and young male players are interested in young females -- or young alien females. It's understandable. I remember Bob Jacob from Cinemaware once that they always had a provocative girl somewhere on the cover, even if she was not in the game. When you are marketing to mostly young men, it helps.

I still had to hide the box from my mom when I brought a game home with a cover like that. I wanted to play it, but I didn't want her to think the reason I wanted to play was because of the cover -- even though that might have been part of it.

AK: We adopted what were similar standards to radio and television at the time. There was something else too. Jay Rosenfeld would not take gun advertisements, or anything salacious, or liquor advertisements. Certainly after the magazine got popular after the first few issues we could have had some very big advertisers, but we were all in agreement that that would not be right for EG.

You worked for Reese for almost five years, right?

AK: Pretty much. Jay made a bad mistake at the end when he got rid of all of us. Basically, Jay was the guy who had faith in all of us at the beginning, when there had never been a video game computer game magazine, and it was totally unproven. He went with it. I will always have good feelings for Jay Rosenfield.

Electronic Fun started not too long after EG started...

AK: It was an imitation published by Richard Ekstract, who was also imitating Video Magazine with Video Review. When Electronic Games became successful, he started Electronic Fun.

As a kid, I liked them both, but I always like Electronic Games a heck of a lot more. I liked that there were multiple magazines.

AK: Electronic Fun was not a very good magazine. The magazine that was pretty decent was named Video Games. Roger Sharp was the editor. We brought him in as a writer and then he got the opportunity to work for a competitor.

That magazine didn't last very long, did it?

AK: No, but while he did it, it was good!

So what you're saying is that Electronic Fun wasn't a competitor -- it was that it was crap.

AK: Electronic Fun was never really a competitor. I think any headway they made was a result of "name confusion".

I think you might be right about that.

AK: I'm not saying every writer was bad, but they had some writers reviewing games at times from photos of the screen shot. I remember a review (from one of their writers) about Kaboom! It was a review of Kaboom!, but he had never played it, apparently -- just seen a picture. He described it as "flaming bowling pins." I mean, there was some not very well done stuff in that magazine.

Tell me a bit about the rise of Electronic Games.

AK: Electronic Games was a tremendous success, really, from the beginning. Our biggest problem was that newsstands had no idea where to put our magazine since there was no other magazine like it.

It was next to Mad Magazine on our newsstand.

AK: Yeah. I remember when I lived in Brooklyn, going to the newsstand at the Hotel St. George, and rooting through the magazines and searching for Electronic Games to give it a better position in the rack.

The first issue was a one-shot. It was "let's do it and see what happens". Jay paid us and we did the issue on a freelance basis. The initial response encouraged him to say "Okay, we'll do it bi-monthly". The second issue was scheduled to be bi-monthly relative to the first. However, by the time we did that one he had increased it to monthly. After that we did it monthly until the big video game crash of 1984.

From your perspective, when did the crash happen?

AK: It's hard to say. I saw bad signs, certainly, by mid-1984. The mass dumping of cartridges, selling them for $3 or $4, alarmed me. I saw some very bad product. That was kind of distressing, because for the first couple years, while I did not like every game, you could tell work had been put in.

When the Activisions and Imagics of the world were making good stuff...

AK: Let's be fair, there was also Games By Apollo.

Yes. I remember Lost Luggage.

AK: Lost Luggage and Wall Ball, a game NO ONE could play. The guys at Games by Apollo could not play it either, as far as I could tell. We brought in the best player we knew, Frank Tetro, who had been a finalist in a Space Invaders tournament -- a terrific player. He could somewhat play Wall Ball. Somewhat. Not really. He could, in fact, return the serve. He was a God in our eyes.

Games By Apollo made the ones that I usually skipped. It was the pages of Electronic Games that informed us to skip them.

AK: We tried to be positive.

How did the original Electronic Games end?

How did the original Electronic Games end?

AK: It folded because Jay fired all of us and brought in another crew that were unable to do it. What was kind of sad about it was that I had told Jay, as far back as mid-1984, that with our name Electronic Games, we should be shifting our focus to computer games because of the problems in the industry. However, Jay was much less comfortable with computers than video games.

It was something about computers. He did not like computers. Maybe they seemed more threatening? I honestly don't know. Whatever it was, we kept our format. I even suggested changing the name to Computers and Video Games. We kept doing it. The circulation went down, but not by much. I think 180,000 was the bottom.

Was the advertising down?

AK: Yeah, the advertising was down, but our main problem was that we did not re-target. When he finally decided to re-target, he for some reason decided to do it with people other than Bill, Joyce, or I.

An obvious mistake, seeing as it only lasted a couple issues, and you guys were the obvious experts at the time.

AK: I know I believe he believes it was a mistake. Hey, it was his property and his right to do it.

Yeah, but the names Katz, Kunkel, and Worley were it at the time. For kids like my brother and I, seeing your names in a magazine or on an article meant it was legitimate. If your names were not on it, it was not genuine. Did they know this?

AK: They did! When they ran out of articles with our bylines on them, our stuff in inventory, the magazine folded.

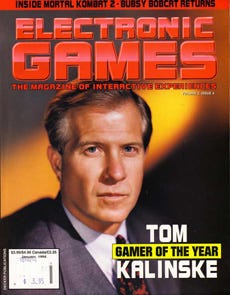

When you guys revisited Electronic Games in the '90s, what did it feel like? Did it fee like the days of old?

AK: I have to give Bill all the credit for that. Bill pursued it with Steve Harris. Steve Harris and I talked about it, and we agreed to revive Electronic Games. It was never our thought. We thought we could do something with Steve Harris. It was his idea to call it Electronic Games. We had not intended to go back that way.

I thought it was a good magazine. Jay Rosenfeld and Steve Harris were very different. Steve was much more knowledgeable about video and computer games than Jay. Jay did not really like that stuff. Jay was sincere, though. He wanted the original to be a good magazine, but he was not himself a computer guy at that time.

Steve liked the technology. The downside was that Steve had very definite ideas, and he was used to getting his way. Sometimes we did things that we might not have done had he not insisted. The whole change to Fusion was endemic.

Fusion?

AK: Steve wanted us to change the magazine to make it more, I guess you'd say, "pop cultural". Since that was something I was very interested in, I had no problem with it. In the years since then, most of my writing has been about things like wrestling or comic books, old time radio, or whatever, so I'm very at home with pop culture -- maybe more than his so-called pop culture writers -- and I thought it was a good idea.

I went out to visit Steve and we designed a magazine. We were both reasonably happy with it. However, when the issue came out it had changed completely. Steve then hired Jer Horwitz at his site and installed him as editor of the magazine. It wasn't very satisfactory, and Steve sold the publications pretty much after that. I was glad to stop working with Jer Horwitz. It was Steve Harris' magazine. He wanted to do it his way, and the end might not have had anything to do with the popularity of the publication.

Back in the '90s, you were pushing hard for people to create their own fanzines. You reviewed them in your magazines.

AK: I said, "Hey you guys, you should do this stuff. It might be fun for you." I did not invent the concept. I had been a participant in science fiction fandom since I was about 17. In fact, I'm still a participant today. I still publish a fanzine. I thought it would be interesting for Electronic Gaming fans to communicate with one another and exchange fanzines, and find like-minded people because it was something I enjoyed as an amateur publisher.

There was one funny thing about reviewing Electronic Gaming fanzines. I reviewed them in a couple places. I tried to be basically positive, but I felt it was important to point out at least one area where they needed improvement so it would not just be sunny sunny sunny, because I felt that would be a disservice to the readers who might be inclined to send money for a sample copy.

I didn't want to people to say, "He did not mention there are no margins" or "He didn't mention the guy can't spell", or "He didn't mention the artwork is atrocious". I tried to include one negative thing.

I used to get these insufferable letters from people who would say, "You don't understand how hard it is to make a fanzine!" Well first of all, it doesn't matter how hard you work, it matters what you produce.

Second of all, I had kind of taken a leave of absence from S.F. fandom. I was active from 1963 to 1976. In that time I did maybe 300 fanzines, including a couple that were pretty popular. They were making a big deal of something I could do in my sleep. It's work, but unless it is fun for you, you should not be doing it.

You did that in the second version of Electronic Games magazine, correct?

AK: Yes, we also had a column that ran in Video Games & Computer Entertainment.

For some reason, those two blur together for me.

For some reason, those two blur together for me.

AK: Well, for us, too. I had been a professional editor and writer for a decade before we did (the first) Electronic Games. I invented that concept (of Electronic Gaming fandom).

But you really were kind. You weren't trying to make a name by ripping people apart.

AK: I rated them by reasonable amateur standards. I never expected them to equal the standards of sci-fi fanzines because the people in sci-fi fandom were a little older and in many cases much more skilled. I did expect them to live up to a level of reasonable content and appearance and most of them did. Look at Joe Santulli. Look at Chris Kohler, who is writing for Wired right now.

So there were people from those fanzines that made it into bigger and better things?

AK: Absolutely! Fandom is its own justification. Whether it is SF fandom or gaming fandom, it's not meant to be a stepping stone to becoming a pro, but the fact is, in many cases, people do acquire the skill to become professional.

Do you think in modern era of the internet, with blogs and user generated content, that people now expect it to be some kind of stepping stone?

AK: Yes, the lines have been blurred. I do not say this to be discouraging, but I am saying it as somebody who recently folded a web site because I found no way of making money at it. The reality is, there is a delusive factor and it has always beset writers (at least for my entire career and well back beyond that) that people confuse the ability to type with the ability to write.

Artists are lucky. People inevitably find out if they can or can't draw. If you can't, you can't. People say to me things like, "I could have written that if I had had the time." That's like saying, "I could have done that brain surgery if I had all that training".

The fact is, I love the internet. I ran web sites starting in the early '90s. After leaving the electronic gaming world, I became the editor in chief and the chief editorial architect at a site named CollectingChannel.com that became the fourth largest site on the internet, when I was doing it.

I love the internet, I spend a lot time with my friends on the internet, but when it comes to writing, there are 100 times more people writing than there should be. When you look at the blogs they are mostly terrible, mostly a waste of time. It's a waste of time for the writer, a waste of time for the reader. Of course there are exceptions, but the average blog is read by seven people.

It is very difficult to gain an audience because there are so many voices.

AK: Yeah, there is a bad signal-to-noise ratio. There is a lot of noise and it makes it very difficult for people to find an audience. There have always been people who felt a yearning to become writers without the desire to submit their work to nay kind of critical scrutiny. They start their own little magazine, now they start a blog. Most of them are not very good. There is no question that the abundance of online material about video and computer gaming has largely destroyed the newsstand magazines.

With several magazines folding over the last year, what do you think of the industry now? I have not really followed print magazines since Next Generation folded a decade ago.

AK: There is a reason for that. They don't respect your intelligence. By the way, neither did Next Generation. They reviewed games they had never seen.

I liked Next Generation because they were the first guys to have a retro column.

AK: Yeah, they did that. They would also trumpet some game was rumored to be under development in Japan as the greatest game ever. Then, a month or two later, they would review it, based on screenshot or something, and it would be "almost" the greatest game ever. Then a few months later the American edition would come out and it would be crap. They were marks.

There was a time when there was such an infatuation with everything foreign, that just that fact made it interesting to people.

AK: Oh, totally true. I'm not saying it did not make sense, but we have to compete with that. Our policy was that we did not sing the praises of anything we had not played. It put us at a disadvantage.

Have you followed casual games in the past few years?

AK: To be honest, I put 20 years in playing games day and night, practically. They would not let me play any game for too long. If I liked a game, they shamed me into not playing. I did not play a game in 20 years when I was not thinking how to write it up, or edit it. You do that for a long time, and for me... it didn't exactly burn me out, but it did reduce my enthusiasm.

I was always into games, from the time I was a little child. By the time I was 12, I was designing board games, which I would play with my friend Lenny Bailes. By 15, I was working on Avalon Hill games.

Were you?

AK: Yeah. I was one of those kids who would write to Avalon Hill asking questions. They gave all the questions to a kid who worked at the office named Tom Shaw. Lo and behold, Tom became president of Avalon Hill!

He was still corresponding with me and he asked me if I wanted to work on some games. I worked on a version of Gettysburg. I advised them to not do it and they took my suggestion. They came up with a different version. I worked on Stalingrad, I worked on Blitzkrieg, and I worked on Sink The Bismark.

They turned those games into very basic computer games in the late '70s and '80s.

AK: I knew their electronic guys very well too. I want to make it clear, though, that I was not the designer of those games -- I was somewhere between a play tester and an assistant. I also did a little play testing with SPI.

Do you still play games, or did your time reviewing them turn you off to them?

AK: I do not hate games. I like a lot of other things now. The one game I play with some consistency is not very technologically advanced. It's called Diamond Mine Baseball.

Kind of like the old MicroLeague Baseball?

AK: It is. The graphics are not nearly as good, but the baseball model is 100 times better. That comes from someone who designed MicroLeague Baseball 2 and worked on MicroLeague Baseball 4. They made some terrible mistakes. They did not know how to complete a product.

What my brother and I would do with MicroLeague Baseball, was play a great team against a crappy team, and then recompile the games stats dozens of times until we had an amazing team from one game.

AK: I'll tell you a funny story. Bill and I were doing gaming seminars on QuantumLink, the predecessor to AOL, and then moved over to AOL when they launched it. With the cooperation of MicroLeague, we offered AOL a MicroLeague All-Star Game pre-play. MicroLeague sent us a disk with the All-Star game rosters computed.

We signed on, they gave us a big room and we started playing the game. We did written color and play-by-play commentary, as though it was a real game. When the first eight guys got hits, we decided there was something not quite right.

The first inning went on and on. It was like kid's game rounders, with people going around and around. Finally, with players being thrown out, stretching bases, and a strikeout, we got through the top half of the inning. We started the next half, thinking, "Now everything will be okay," Bill and I assured each other.

We were wrong. It was the same thing. We played through an inning and a half and it was a football score. We just said, "We are not doing this."

You were doing that live?

AK: Absolutely. We had two computers set up. We were really just banging away at it and really giving them a show. I contacted MicroLeague; Paul Kelly was in charge at that point, and I said "Paul, we had a disaster!", and he said to me "Oh yeah, there's a mistake in the disk". Thank you!

Back in Electronic Games days, did you ever visit the original Atari, Inc.?

Back in Electronic Games days, did you ever visit the original Atari, Inc.?

AK: Oh yes! Bill and I each visited Atari. Bill might have gone two or three times. I went when they were going to introduce the 5200. They had me play all the games and write the blurbs for the covers.

You wrote blurbs for the covers?

AK: Yeah, some of them anyway.

What did you think of the 5200?

AK: I thought it was the same games again. I thought it was going to be a failure, but I did not tell them because they did not ask me.

One of the things about CES was that we had to be careful. We could destroy a game with an offhand comment. I tried to be very circumspect about what I said. I tried to not judge a game by the 30 seconds I saw of it. You need to play a game. The play-action is everything. In the long run, you can stand a game that plays great but looks bad, but a game that looks great and plays bad is unbearable.

Did you ever meet the Tramiels from Atari Corp.?

AK: I knew who they were. They had come from Commodore. I think Atari Corp. had a lot of policies that were not going to help the company survive, but I don't think the Tramiels were the devil.

Atari as we knew it had been flushed down the toilet by Warner Bros. anyway. A lot of Atari fans were mad at the Tramiels, but they were basically some guys who nursed along a famous logo for 10 years or so with little leverage to do much else.

AK: Exactly. When they did it, it was almost like a side issue. There was Nintendo and Sega and those were companies people were caring about. I really didn't take it seriously. It's kind of like Intellivision. It continued for several years as its own company, but you couldn't judge it along with a regular company with a big R&D staff.

And the Tramiels did come back, but like you said about the 5200, they just sold the same games over and over again.

AK: Yeah, but Nintendo has done the same thing with their games.

Sure, but Nintendo made major improvements every time out.

AK: Yeah, but so did Atari. However, they were starting from such a primitive system that the improvements had to be small by comparison, and maybe not as good as the fans wanted them to be.

You guys never scored your reviews, right?

AK: In Video Games we ended up with letter grades or something. I felt that if the review was well enough written, you could tell how the reviewer values the game.

My personal feeling is that number and letter grades just allow people (like me) to skip the written content in lieu of the score.

AK: It reduces the magazine to a bunch of letter grades. I believe that video games and computer games are artistic creations like a radio show or a TV show, or a movie or a CD, and they deserve the same kind of consideration.

Do you think that kind of success and trust you had with the readers when you published the original Electronic Games could be recreated today?

AK: I think if any kind for magazine is going to be successful these days it has to be on the internet. Honestly, I don't think that magazine is being done now. I don't see everything, but my gut is that does not exist today.

There are pieces in different places, some good authors and journalists out there, but not really all in one place.

AK: I think some of the smaller sites need to band together and pool their resources. They need to stop duplicating efforts.

I usually follow single writers these days. For instance, there is game journalist who, 10 years ago, gave Roller Coaster Tycoon a good review. He was one of the people who saw the brilliance of it. I've followed his stuff ever since.

AK: You know, the field is losing a lot of those good writers. Steve Kent, for instance. He was a good journalist.

Steve Kent was great.

AK: Yeah, he's writing novels now. He's sold several science fiction novels. I thought he was very good, but his incentive is not very high to do this stuff any more. There are not many places where you can really make a good living writing about electronic gaming, and if you can't make a living out of it, it means the best writers won't be doing it. For example, I know that Bill Kunkel is now doing some writing and he's a terrific writer. However, I think he's doing it out of personal commitment.

Yeah, he's doing a lot of other jobs at the same time.

AK: Yes, he's kept his hand in a lot of different things!

Do you recall the first game you played that made you think games could be "art" or an "artistic creation"?

AK: Well, my original experience was with board games and I considered them an artistic creation. Take a game like Monopoly. When you really look at Monopoly, it's quite a thing. It was also America's great folk-art game. It was not done by a designer sitting in an office, it was done by people on their dining room tables and barrowing ideas from each other and seeing versions that other people had made.

Eventually Parker Brothers bought a couple versions and couple minor versions, but there is still a version of Monopoly out there that is not owned by Parker Brothers. It's called Anti-Monopoly.

How about video games?

AK: I loved pinball games and the baseball games n the arcade, and Joyce was a great marksman with the shooting games, and we both liked skee-ball. When they first put Pong in the arcades it was like a revelation. It was so simple, yet you could see how they could make so much more out of it.

You could see companies like Atari elaborating on Pong with soccer-like games, but then we had Breakout. That was different, you could see how it came from Pong, but it had a little color and a little strategy. Then we had Space Invaders, and that game had a lot more strategy and a lot more flair. That rumbling beat, and the little guys marching down the screen. You saw games like that and you thought, "Wow, this could really be something."

Then there were two other games that need to be mentioned. The first is Castle Wolfenstein for the Apple IIe. I was so addicted to that game, I would play for hours. I would play it, then play some game I had to review, then I'd go back to it. The other game that I liked was Wizardry. Robert Woodhead and his partner did a good job designing the game. I loved the game. It was like D&D, which I also played.

We had a little D&D game that I had modified almost into another game to fit the idiosyncrasies of Joyce and Bill. They wanted certain things in the game and those things were not really the way D&D was organized, but they were by the time they played it in my living room!

Anyway, I liked Wizardry a lot. I did discover a little bit of glitch though, something you could do to ratchet your player up as far as possible. Then they came out with a disk that would do it for you. I loved that game. I played it and played it and played it, and eventually Joyce asked me to stop and play other games.

Did you ever play M.U.L.E.?

AK: We were very friendly with Ozark Softscape and Dan Bunten... who I guess became Danielle, and died kind of young, actually.

Yeah, that was really sad.

AK: He was a super nice guy. Talk about a person with a sweet nature. He didn't like those violent games at all. His idea was always to do games that were interesting and perhaps challenging, but not really violent. A game that he did do that was a little violent was Seven Cities of Gold. I loved that game. I played that game all the time.

That is still one of my favorites. I was always amazed at that option that would build an entire world for you.

AK: Yeah, it was great. Ozark Softscape did some wonderful work. I think the industry turned in a younger direction, where their more cerebral approach simply did not get the attention it deserved. I think often the video and computer game industry has harmed itself by focusing only on a very limited demographic when there is a larger one out there.

What do you think about the game industry today?

AK: I think that gaming is a great hobby and I think the industry has done a good job of serving the 24/7 all-out gamer, however I think it might be time look to wider audience -- casual games for instance. Not just with Tetris or Boggle style games, but other games where the play-action, the play mechanic, is more straightforward, more easily learned, but still hard to master.

If the industry is going to continue to prosper, it has to think in terms of a wider audience that might not be as gung-ho as the hardcore. They have to move that way, because the 24/7 gamer, to "total immersion" gamer, is moving online. They want an enveloping, wall to wall experience. However, many people can't do that. I might have an hour to play a game at night. Adults just don't have the time to do that.

What do you think of casual games?

AK: Those are what we used to refer to as "family social games". I've been predicting for years that there would be a turning away from the geek games.

Games for the guy in basement with the headset on?

AK: Well, I mean the complex games which essentially encourage you to leave this reality and spend all your time energy and mental processes on another reality. I think that for some people that is something they want. They are not comfortable in this world and they want another one. I understand that perspective, but I don't think that is most people. I think most people want a little fun a little entertainment. I think they want a game they can understand, but might take a little time to master.

One final question: The emergence the independent press (i.e. Electronic Games magazine) gave the consumers a way to evaluate games that they did not have prior to winter 1981. Instantly the gaming "community" was established, and through that community, the empowered consumers did not have to rely on marketing information alone to make their game-buying decisions.

Looking back, do you think the emergence of this video game press, the one that you basically invented, has had a net positive, or net negative effect on the video game industry as a whole?

AK: Bill, Joyce, and I felt a deep responsibility to the gamers when we started Electronic Games. The magazine needed advertisers and it was in our interest to take a positive spin, but we never knowingly lied to the readers or touted games we didn't think were good. I never invested a nickel in any game company, though I certainly could've made a lot of money doing so, because I didn't want something like that to influence my judgment.

I think the game companies have a right to market their products. Comsumers have a right to unbiased, accurate information to help them make those hard buying decisions.

---

Images courtesy Retromags and Vintage Computing and Gaming.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like