13 years ago, The Behemoth's classic run and gun title received its first commercial release.To honor this indie game milestone, we present this postmortem that ran in Game Developer magazine in 2005.

13 years ago this month, The Behemoth game studio's memorable run and gun title received its first commercial release after an early Flash prototype caused a sensation on the site New Grounds. To honor this indie game milestone, we present this postmortem on the development of the game that first ran in Game Developer magazine in May of 2005. It was written by The Behemoth co-founder John Baez, who was producer of the game, and Tom Fulp, creator of Newgrounds.com and another co-founder of The Behemoth who co-created Alien Hominid.

ARE YOU A BURNT-OUT SHELL OF YOUR FORMER SELF DUE TO INHUMANE working conditions as you toil away in your cube at GloboCorp Games? Are you afraid to be the first to leave work for the day because you’ll end up on The List? Does the word “crunch” make you break out in a cold sweat, even if you are just talking about breakfast cereal? If so, leave work early today and join us on a romp through indie heaven and hell as we bring you into the studios of The Behemoth and the making of Alien Hominid.

Alien Hominid is the debut title from The Behemoth. A PlayStation 2 and GameCube console title (with an Xbox version having now gone gold in Europe), Alien Hominid allows players to race across the earth in frantic recovery of their spaceship. Construction of the console version began on April 1, 2003 and the game shipped on November 17, 2004. As a traditional 2D side-scrolling shooter with a twist, Alien Hominid has received numerous awards, including Independent Games Festival 2005 awards for Technical Excellence, Innovation in Visual Art, and the coveted Audience award.

The completeAlien Hominid team, taking a break after curing cancer.

Alien Hominid began life as a Flash game built by Dan Paladin and Tom Fulp. It was rolled out on Newgrounds.com (Tom’s “other job”) in August 2002, and to date has racked up more than 10 million views on Newgrounds alone. Soon after its release, a link to the Flash game landed in the inbox of John Baez, who was working as an artist at Gratuitous Games on an Xbox port of Raven’s Soldier of Fortune II for Activision. John immediately realized that whoever brought the title to consoles would be a hero.

At the time, Dan was with Presto Studios, having recently wrapped up artwork for Whacked!, an Xbox Live launch title Presto was developing for Microsoft. In the fall of 2002, Presto decided to shut down operations after Whacked! shipped, and Gratuitous hired the remnants of its art department. Suddenly, the artist for Alien Hominid was just down the hall.

A few months later, the owner of Gratuitous Games decided to shut down his company. Gratuitous had made a name for itself by doing ports for Midway, Activision, and Crystal Dynamics, but each year it was harder to get quality work, because many of the big publishers were using their in-house studios. Once Soldier of Fortune II went gold, Gratuitous would close.

Not wanting to go back into the tight job market, they decided this was a perfect opportunity to make a console version of Alien Hominid. Dan sent Tom an email that basically said, “Some guys from work want to take a lot of money out of the bank and make an Alien Hominid console game.”Tom decided to humor him and replied, “Okay!” Eighteen months later, Alien Hominid was on store shelves.

It’s one of the first web games to cross over to consoles.

WHAT WENT RIGHT

1) SMALL, EFFICIENT TEAM

Part of the success of Alien Hominid was that we kept our team very small throughout development. A worldwide, multi-SKU console title on the current generation of hardware will often take upwards of 25 people to make. Our small team size meant everyone had to do double or triple duty, but it also meant that our risk was reduced because we didn’t have a bunch of guys standing around waiting for meetings or needing to be told what to do.

Part of the success of Alien Hominid was that we kept our team very small throughout development. A worldwide, multi-SKU console title on the current generation of hardware will often take upwards of 25 people to make. Our small team size meant everyone had to do double or triple duty, but it also meant that our risk was reduced because we didn’t have a bunch of guys standing around waiting for meetings or needing to be told what to do.

Aside from Tom, all of us had worked on the production side of game development before, so our learning curve was relatively flat and we could concentrate on creating the game instead of learning new software. This, combined with the fact that we had all worked together at Gratuitous is probably the number one reason we succeeded.

Being small meant that each person had more responsibility than was probably healthy, but we grew into our new roles well. For example, John’s background was in architecture and level building, but in the new company, he would be the strategist, money guy, business guy, and toilet bowl scrubber. Dan would move from being an artist to being an art director, now with the added fun of reversing roles with his old art director.

In the end, our core team of eight full-time developers and a handful of part-time friends brought back to life the garage atmosphere most people in the game industry thought died out a decade ago.

2) OUR OWN TECHNOLOGY & IP

Being small and self-funded meant we couldn’t spend money on middleware. Knowing this from the start let the programmers rip into the engine, aware there would be no one to turn to if things didn’t work out. It was also key for us to simultaneously develop for as many consoles as we could since we had the experience from our Gratuitous Games days and it would be a shame to squander that advantage. Publishers took notice when they saw it running on three consoles, which was a big bonus later on. At the same time, we knew we would not be able to develop our own in-house content creation tools, so we had to build our engine knowing that we would be using off-the-shelf content creation software like Flash and Photoshop.

In the beginning of development, we experimented with 3D rendered versions of the characters. They looked really slick, and much more “professional” than the original Flash version. Dan prepped a 3D cel-shaded version of the alien, which also won our hearts for a moment. As we progressed with this style, we found it was totally lacking the charm and character of the original. Once the decision was made to drop 3D altogether, we developed a tool that allowed us to easily incorporate Dan’s vector art, hand-drawn with a Wacom Tablet.

3) SELF-FUNDED

From the get-go, we knew it would be hard to get anyone to fund our risky game venture. Although we had been approved to develop through the console manufacturers’ unsigned developer programs, many of the people we talked to insisted a 2D game would never be approved and we were wasting our time. Others believed we were too small to pull it off, or we didn’t have enough business sense because we were down-in-the-trenches workers, not up-in-management guys with good connections throughout the industry. Naive or stubborn, we believed in the project and knew it could make money, so we assumed the risk of funding it ourselves. The initial “seed capital” came from John mortgaging his house, which had seen a lot of appreciation during the San Diego real estate boom.

We thought this initial loan would cover the complete development of the game, which we roughly estimated at nine months. However, as the game continued to become more and more rich, we decided to give it more time to grow organically. Josh Barth, Scott Fadick, and Chip Burwell, critical programmers on the project, all kept their wages far below market rate to help keep the lights on, and Tom started dumping in money to continue funding and keep us strong. At times, this put a lot of strain on the team, but since we could see the game getting stronger on a week-to-week basis, it made it all bearable.

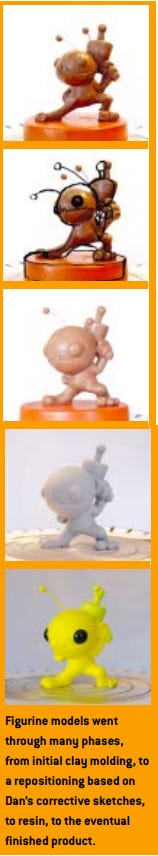

As much as we believed the game would eventually pay for itself, we realized we needed to create some alternate revenue streams to keep ourselves going, so it came time to explore merchandising. The great thing about owning your intellectual property is you can do whatever you want with it. We decided to make t-shirts, skateboard decks, and figurines. In order to maintain a high level of quality control, we decided to bypass middlemen and produce everything through our network of friends. The figurines were sculpted by Clint Burgin, a local artist in San Diego. Clint had a friend who made regular trips to China, so we paid him to be our factory liaison.

Ultimately, we discovered that by self-funding we had stumbled upon any number of revenue streams. Since our North American publisher had no presence in Europe, we decided to license the game on a per territory basis. Initially, we accepted mail and check orders only for the figurines and other merchandise, but closer to the console release we launched our online store and worked out the kinks of the fulfillment. By creating a multi-SKU title that we sell online with cross-promotional merchandise, we’ve avoided the traditional developer/publisher relationship of a single, worldwide revenue stream.

4) SELF-PROMOTED AND CULTIVATED FANBASE

One thing that gave us all great confidence in the success of Alien Hominid was the existing fan-base on Tom’s site, Newgrounds.com. The Flash version already had over five million downloads when production began, and Newgrounds entertains millions of unique visitors every month. Tom was able to actively market Alien Hominid online, so even without paid advertising, we still moved units. We were also able to conduct polls relating to the game. To our astonishment, we had over 65,000 people take a lengthy poll which queried everything from how many times the person had played the prototype and where they bought games to what gender they thought the alien was.

As the owners of our intellectual property, we were free to promote Alien Hominid anywhere we wanted. By this time it was July 2004 and we had just received concept approval from Sony, so Comic Con 2004 was going to be the first official unveiling of the PlayStation 2 and GameCube versions. We set up a big, beautiful booth at the show and promoted the nearly finished game to 87,000 attendees. We even made the cash register sing by selling figurines, t-shirts, and skateboard decks. The hit of the show was the yellow alien antenna headsets we gave away to the crowd. We only brought 5,000, but should have brought at least five times that many; the demand was way beyond our expectations. The event won over a lot of new fans and landed us in several magazine spreads and on TV.

5) A NEARLY FINISHED GAME=MULTIPLE OFFERS

Back in 1998, John attended the Game Developers Conference in Long Beach, Calif. In one of the sessions, the lecturer commented about how he started his company in his basement and had done a tremendous amount of work on a shoestring. It was a huge feat, and he recommended that no one in the audience follow in his footsteps. People refer to this as the “don’t try this at home” talk. However, in case someone did want to attempt it, he recommended that you nearly finish the game before looking for a publisher so that there is less risk on their end. The speaker said he had received multiple offers for his game due to this foresight. Well, lo and behold, five years later, John found himself cold calling publishers with Alien Hominid stuffed in his backpack. Far beyond the mythical “vertical slice,” our pitch package included a robust copy of the game running on any of the three consoles the publishers cared to see it on. We also developed a slick presentation that would ultimately be refined over the next few months as we visited with more than 20 publishers.

While some of the top tier publishers were quick to tell us, “Thanks, but no thanks. Your game is fun but won’t sell a million units,” we kept at it. Finally, a few months before E3 2004, we started to receive serious offers. In a last attempt to get in front of as many publishers as possible, we took Alien Hominid to the first U.S. Game Connection held during GDC 2004. Run by a nonprofit group of fashionably dressed French guys (Lyon Game), the concept sounded great even if it seemed expensive. John was able to fly in on Tuesday morning, grab a cab to the Connection, check in, set up, and display the game running on all the consoles to eight publishers, pack up, jump back on a plane, and be back in San Diego by dinner time. The feedback we received helped us move forward with our negotiations and helped us begin meeting European publishers.

WHAT WENT WRONG

1) WE NARROWED OUR CHOICES TO JUST TWO PUBLISHERS

Looking back, almost a year to the day that we signed our contract, we realize now that we should have done a complete and thorough due diligence on each and every one of the publishers who made us formal offers. It was something we really didn’t know how to do beyond the cursory checks and it seemed to put a shadow on the negotiations when everything was looking rosy at the start of a relationship. But these days, when developers and publishers are closing their doors left and right, it is critical for a developer to really get to know their future publisher. Forget about being nice. Roll up your sleeves, put a pair of rubber gloves on, and find out who you are really dealing with because it takes a lot of cash to publish, distribute, and adequately market a game. This is especially critical if the developer is bringing new IP to the table or if your publisher is just getting established. You can’t launch a franchise from scratch without extensive marketing.

Looking back, almost a year to the day that we signed our contract, we realize now that we should have done a complete and thorough due diligence on each and every one of the publishers who made us formal offers. It was something we really didn’t know how to do beyond the cursory checks and it seemed to put a shadow on the negotiations when everything was looking rosy at the start of a relationship. But these days, when developers and publishers are closing their doors left and right, it is critical for a developer to really get to know their future publisher. Forget about being nice. Roll up your sleeves, put a pair of rubber gloves on, and find out who you are really dealing with because it takes a lot of cash to publish, distribute, and adequately market a game. This is especially critical if the developer is bringing new IP to the table or if your publisher is just getting established. You can’t launch a franchise from scratch without extensive marketing.

For us, the results of a good due diligence alone would have probably reduced the field considerably and would have allowed us to further pursue offers that were beginning to form. Ultimately, we decided that one publisher was pretty much like another when in fact they are not. Add to this a big helping of being relieved to have any offer at all (let alone four) and the belief that we knew what we were doing when in fact we were pretty clueless. Those are the lessons you learn with your first deal, which is what makes you stronger for the next deal.

2) DISTRIBUTED STUDIO DIFFICULTIES

When we started with Alien Hominid, Tom was living in Philadelphia and the rest of the team was in San Diego. Over the course of development, Dan moved from San Diego to his hometown in Cleveland, then to Philadelphia to work directly with Tom as he programmed gameplay, then back to his hometown in Cleveland after the game shipped. Matt Harwood, our music composer, was in New York, but all of the source files and console coding was done in San Diego, which meant we had to depend on our Internet, VPN connections, and Source Safe to work from all over the country. To put it gently, the experience was horrible. It took forever to check content in and out of the system, and remote computers often dropped the connection mid-transfer. For security, we used SST for communication instead of AIM or MSN. I don’t know what the problem was, but SST was slow and lagged too much. We plan to use different source control and messaging tools on the next project.

During development, Tom made frequent trips to San Diego, staying for several weeks at a time for crunch sessions with the team. The trips to San Diego were definitely the most productive. It was great to be able to shoot ideas back and forth in real-time and feel the excitement and energy in the room. We would all get completely pumped and would work insane hours. Not having to deal with an Internet connection, Tom was able to get infinitely more work done in a short amount of time. Having always considered himself to be a champion of telecommuting and distributed offices, Tom now admits it is best when you stick everyone in the same room together.

3) OFF-SITE CONTRACTORS

On the topic of sticking everyone in the same room, this is especially true for short-term contractors. We were a small team with a lot of content to produce, so bringing in friends as content creators seemed like a great idea. We sought out some of the best online talent we could find to assist with development, but in the end, a lot of artwork was redrawn and code was rewritten. Their work was done early in the project and as it lengthened, we decided to stop using contractors. These were great artists and programmers, but we didn’t manage the sudden team growth well and in the end, wasted a lot of time and money having things developed that weren’t put to proper use. When everyone is already incredibly busy working on their own things, it’s hard to maintain good communication with people who are sharing the workload from distant cities. In the future, we plan to keep all content creation local, whether it be local to the San Diego or Philadelphia office. We don’t intend to rely on anyone we can’t meet for lunch.

Alien Hominid features quite a few minigames, including this retro-styled PDA themed retro platforming game.

4) SCOPE CREEP

Forget storyboards and design documents! Aren’t outlines for high school English class? Dan and Tom are both pretty impatient when it comes to planning. Their ideas come as a stream-of-consciousness river full of mud, rocks, and the occasional gold. Making Alien Hominid was a matter of panning for that gold on a daily basis. Planning ahead was like panning in stagnant water; months later, you’re stuck with the same nuggets that were there when you started. Everything great about Alien Hominid comes from our constant desire to add new things and to let the design grow organically. However, that was also a big problem and caused a lot of frustration for the rest of the team on many occasions.

The hardest part of Alien Hominid was calling it “done.” The programmers built a development system that made implementing new features very easy, but new features always introduced new bugs and there came a time when we couldn’t afford to have any more new bugs. We called this time “content lockdown.” We actually had several content lockdowns through the course of development. This was the equivalent of a parent saying, “Playtime is over, time for bed!” You always know you can stay up for 15 more minutes. John was the parent while Dan and Tom were the kids, full of sugar with toys all over the floor, not ready for bed. The thought of no longer being able to add neat things to Alien Hominid caused stomach aches and insomnia for many nights. It is the crux of anyone who creates something; you’re never completely satisfied with your work and there is always room for improvement. In the future, we all hope to stick more closely to a plan, for John’s sanity, if nothing else.

5) TESTING, TESTING, TESTING

As our Alpha deadline loomed on the horizon, we decided we should begin a routine testing regimen. The other publishers we had worked for in the past always had their own quality assurance teams and did not require assistance from the developer; however, we knew that our publisher was still ramping up and time was getting critically short.

Originally, we used Dan’s fiancée who could school anyone in just about any game, but when they broke up, we knew we’d have to get a full-time replacement. We decided the testers should be located in San Diego with the console team, so we ran Monster.com ads and quickly had a stable of testers to choose from.

Our publisher brought in their testers in August, but we soon realized the game wasn’t getting the punishment it deserved, as our internal tester Emil was able to log more bugs than the whole crew of testers at our publisher. Testing would haunt us after the launch of the game, even though the game had gotten a clean bill of health from us, our publisher, and Q/A at both Sony and Nintendo.

After Alien Hominid hit retail, a humorous bug began appearing on user forums. It seems that when a single player exhausted their stock of lives and began to use the second controller and Player 2’s lives, one boss would exit stage left in search of Player 1. In a way, this bug was kind of charming, as if the boss wanted Player 1 to come back to enjoy another pounding. Ultimately, it was frustrating for only a few players, but it was unnerving for us.

ADVANCE TO NEXT LEVEL!

In the end, we chalk up a lot of our successes and problems to being a new developer. We learned a lot about planning, hierarchy, marketing, testing and more. We went far beyond where any sane developer would go by manufacturing our own merchandise, opening our own online store, and doing our own marketing and PR. Want to know where to buy the best industrial 1-inch button-making machine or where to find the best walk-around suit manufacturer? Ask us. Need a trademark lawyer in Europe? We’ve got one.Yet these lessons came with a price beyond the hard knocks of learning. When “quality of life issues” is the buzz term of the day, being independent makes our lives that much more stressful because there is no one here to give us a paycheck every two weeks or load us up with benefits. Just imagine going to your spouse and saying, “Honey, I want to start a video game company and the hours are going to get worse, not better. I won’t be drawing a paycheck anymore and we’ll have to liquidate our savings accounts. And one more thing—I need you to sign the mortgage on the house.” Believe us, the only reason this game ever made it to the shelves is because of our wives, kids, and the girlfriends who stuck by us. They never once stopped believing in our crazy dreams.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like