Bundling in the Gaming Industry

Bundling has been a major part of all markets since consumerism began, and industry takes no exception. As bundling has evolved in our industry, different effects and consumer behaviors have occurred to bring the practice into question. Lets examine them:

Please Note: This was written as an Honors Thesis at DePaul University, and as such, is written in the realm / setting of academia.

Acknowledgements

Several different people came together to make this piece what it is, and these individuals must be acknowledged. This piece changed and evolved over its timeline, and this change is a direct result of the energy, guidance, effort, enthusiasm, opinions, and knowledge of the following people. To put it simply, I wrote the thesis, but they made it what it is today.

So, thank you….

Brian Schrank, Thesis Director: For constantly pushing both this project and myself with every opportunity you had. For never accepting what I gave you at first glance and always creating more questions than giving answers. For ensuring that I only presented by best, despite the challenges that doing so brought up.

Jay Margalus (@jaymargalus), Second Reader: For going above and beyond what was required or expected of you as a second reader, and becoming so involved with the project. For countless tweets, Facebook chats, email chains, and office hours. For ensuring that as many players in the indie space were pulled into this as possible.

Alex Ting (@uTINGme): For providing one of the most extensive, fascinating, and entertaining interviews I have ever been involved in, regardless of subject matter. For ignoring stranger danger and befriending a random person who contacted you on the internet.

Aaron San Filippo (@AeornFlippout): For your thoughts and opinions on bundling, and for being so quick and generous with your answers.

Rob Lach (@lachrob): For providing an excellent interview which my phone then immediately destroyed.

Erik Hanson (@Erik_A_Hanson): For giving necessary guidance about assigning values to opinions when the thesis hit a significant snag.

Rose Spalding, Nancy Grossman, and Jen Kosco: For ensuring that students like myself had the opportunity to pursue this thesis project, and for allowing me to pursue something so fine tuned and geared towards my personal interests and growth.

________________________________________________________________________________

Bundling In the Gaming Industy

As a socioeconomic practice, capitalism has one chief goal: to generate money. The methods behind this goal are fine tuned to each capitalist market and industry, but as a whole, once a practice has demonstrated its profitability it is there to stay. This occurred with the practice of bundling, and selling multiple products together is now commonplace in the majority of markets. One such market is the video game industry. Despite how commonplace bundling in the gaming industry is today, the effects this practice has on the industry are heavily debated. People argue for and against bundling, both in terms of what it does to a games value and to the industry as a whole. Even with this disconnect, bundling is an extremely positive movement in the industry. Despite the argument against bundling, and the economic trends bundling creates, developers need to bundle their games for both the economic returns and the non economic benefits bundling generates.

Bundling has been a part of markets for as long as markets have existed. In this regard, there should be little surprise at the emergence of bundling in the gaming industry. However, as the gaming industry undergoes changes, companies are constantly adapting to those changes. Given this constant state of evolution, several different issues have been voiced by prominent industry members with regard to bundling. Although this concern is present, it can't be fully discussed until an understanding of bundling is gathered.

Bundling In All Markets:

Consumers currently perceive bundling as items being sold together for one price, but this isn't exclusive when referencing a bundle. Xeni Dassiou and Dionysious Glycopantis, professors of the department of economics at City University in London express this when they write about "three different pricing strategies that a firm with monopoly power can pursue: (i) pricing and selling goods separately (pure components pricing), (ii) offering the goods as a bundle only (pure bundling), or (iii) by selling the goods both individually and as a bundle (mixed bundling)" (Dassiou & Glycopantis 324). This is significant because with different types of choices for consumers, there are different studies and outcomes. As demonstrated above, a 'bundle' could refer to many different options, each with their own unique set of variables.

Based on these definitions, the vast majority of goods consumed will be pure components pricing. However, when a bundle does arise, it will be exceptionally rare to see pure bundling. Given this, mixed component bundling must fall under heavy scrutiny. However, it isn't simply enough to say 'mixed bundling makes money' because this statement is far too broad. The effect of bundling are very different based on the consumer, the items being offered, and the correlation between the two. This in turn means that different bundles make money for different reasons. However, one of the most common bundles is the negative dependence bundle, which occurs when bundled items don't have an effect on the profitability of each other. Product A does not drive the sale of product B, yet when product A and B are together in a bundle, profit is reached.

Yongmin Chen and Michael H. Riordan of The University of Colorado express this profitability in the negative dependence bundle when they state "a multiproduct monopolist generally achieves higher profit from bundling than from separate selling under negative dependence. Stigler (1963) and Adams and Yellen (1976) found by various examples that bundling can be more profitable than separate selling when values for products are negatively dependent" (Chen & Riordan 42). Here Chen and Riordan are demonstrating that bundle items don’t have to be connected in order to drive profit. That's not to say that items from separate markets should be bundles, such as a child's toy and an R rated film, but Chen and Riordan demonstrate that items can be bundled without a necessity for each item to relate to the other.

However, an argument can be made that bundling in the gaming industry operates under a positive correlation, as sales of games will drive the sale of other games. Fortunately, Chen and Riordan prove that a correlation between items, known as positive dependence, creates similar results. "Thus, for all admissible marginal distributions, there is some range of positive dependence for which bundling is profitable. This range is larger when market shares under separate pricing are closer together" (Chen & Riordan 47). This revelation by Chen and Riordan is significant for two reasons. First off, it demonstrates that a correlation and a dependence between the two items in the bundle still results in a significant profit. This is important as many consumers will perceive this correlation in a game bundle. Secondly, it demonstrates that the range for positive dependence is increased when the separate prices of goods are closer together, which is often the case in software bundles.

Not only is mixed bundling favorable given the profit return, but it also creates more consumers, regardless of what value these consumers place on the individual goods. This is so because consumers who value only one product will refuse to purchase that product in a pure bundle, simply because they don't want the other product that pure bundle would come with. Given this consumer behavior, presenting these consumers with a mixed bundle in place of the pure bundle will sort them into two separate groups, the consumer who buys the bundle, and the consumer who buys the individual product.

Brooks Pierce and Harold Winter, members of the Bureau of Labor Statistics at Ohio University support this claim when they state "when a firm faces some consumers who greatly value purchasing good 2 given good 1, and other consumers who place little value on purchasing good 2 given good 1, mixed bundling has an advantage over pure bundling in that it allows the firm to sort consumers into different markets (Pierce & Winter 813 - 814). Pierce and Winter demonstrate here that mixed bundling creates more profit for the bundling company, as a pure bundle would have to be priced much lower if the company wants both consumers to purchase the bundled products. They also demonstrate that ideal of sorting the two consumers into separate consumer groups, which allows the company offering the bundle to market to these two consumers differently, and thus offer them unique consumer experiences.

Additionally, bundling is superior to other price methods that corporations may consider. Another pricing method commonly compared to bundling is expressed by Jon Aloysius, Cary Deck, and Amy Farmer, whom write about it in an article with the International Journal of the Economics of Business. In the article, they state "as an alternative strategy to bundling, Aloysius et al. (2009) introduced the notion of sequential pricing with discrimination, where sellers observe the order in which buyers are quoted prices and condition subsequent price quotes on previous purchase decisions" (Aloysius et al. 26). Though this is most commonly associated with the stock market, this ideal can also be equated to waiting for the price of a game to drop. Individual to a bundle, consumers will wait and try to lowball other consumers, thus buying the game at the lowest possible price. This ideal compares to bundling because of the similarities of consumer behaviors, as well as emergent consumer behaviors with game purchasing. In the gaming industry, consumers often wait for games to end up in a bundle, and purchase these games for cheaper than they would sell as an individual item, thus drawing the similarity to sequential pricing with discrimination.

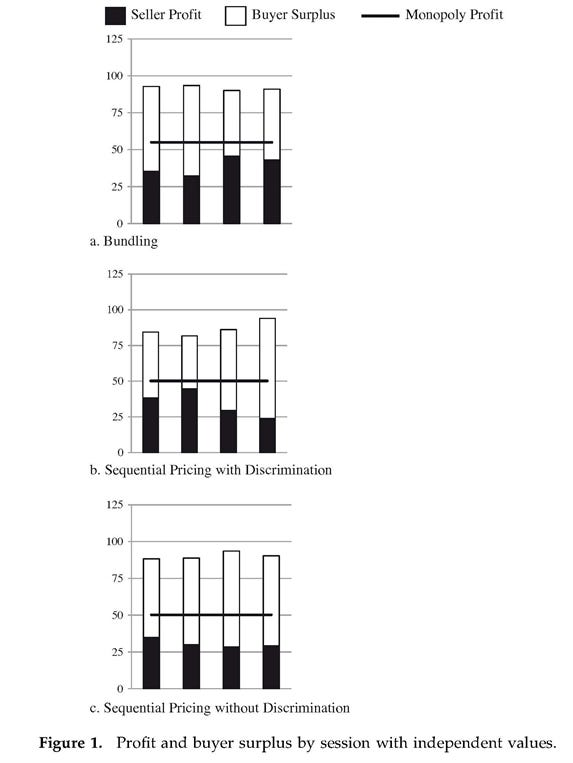

However, despite the similarities in philosophies adopted by consumers, sequential pricing is still a different pricing strategy, and as such, offers different variables to examine. Despite this, Aloysius, Deck, and Farmer go on to prove bundling superior to sequential pricing. This is confirmed when they state "seller profit is significantly greater (p = 0.043) with bundling (average profit of 39.0) than with sequential pricing without discrimination (average profit of 30.7) (Aloysius et al. 36). Here it is very obvious that bundling creates more profit than sequential pricing. Ergo, items in a bundle will generate more funds than individual items operating under sequential pricing. This is seen in their Figure 1, where certain items create less profit for the seller, but as a whole the monopoly profit is higher than other sequential pricing methods.

The benefits and advantages of mixed commodity bundling are clearly evident. This is significant because the vast majority of bundles in the gaming industry operate under mixed commodity, as these games are available through several different distribution methods. However, as with any element of a consumer market, the social norms and expectations of bundling are changing to follow the evolving consumer patters. As the gaming industry has evolved, different cultures among gamers have also evolved, and these cultures play a crucial role with bundling in the gaming industry.

A Brief Overview of the Gaming Industry:

As a whole, the games industry behaves like any other market. Consumers purchase products, and the success of those products is a result of how well they are made. Studios are constantly working to improve their games, and create repeat customers. Despite these parallels, the rapid change in technology causes equally rapid changes in the gaming industry, and the consumer behaviors that keep the industry flowing. The game industry has changed in several ways since its beginnings, but the rise of the independent game studio is both one of the biggest changes the industry has experienced, and one of the main reasons bundling is so prevalent today.

Prior to the seventh generation of consoles (Xbox 360, PS3, Nintendo Wii), the internet didn't have much of a foothold in gaming. However, with this console generation, the internet exploded into gaming, allowing for players to compete in multiplayer games. Although this had an effect on the market, introducing the internet into gaming brought about the indie developer, which had a much more profound effect. Prior to the internet's inclusion in the gaming market, games were made by AAA developers. For several years, the industry was dominated by AAA developers, which are studios that work on multibillion dollar games that take years to develop. These are games that you see today like Call of Duty, Assassins Creed¸ and Titanfall. Given the financial commitment necessary for these projects, AAA games are backed by publishers, who give developers the capital necessary to create the game and then take a cut of the profits. However, with computers and consoles taped into the world wide web, computer programmers began making their own small games, and distributing them on the internet. This phenomenon first started with the iPhone and its app store, but eventually expanded to various distribution platforms offered for consoles and computers.

Despite being a retail chain, GameStop demonstrates this shift towards indie developers well in a recent SWOT analysis. In it, MarketLine states "there has been an increased shift towards online gaming and away from console games. Further, in the second quarter of 2012, sales of content in a digital format rose 17% compared to the second quarter of 2011" ("GameStop SWOT" 7 - 8). Purchasing games online offered a convenience previously unseen in the gaming market. Consumers didn't have to go out to a store to get software, they could simply stay at home and download the games they wanted to play. Purchasing games online and through the iPhone app store was also prone to impulse buying. Consumers could tap a few buttons on their phone and buy a game, or do the same on the internet. The game would be installed immediately, with a small charge coming to the consumer. This simplicity was a great contributor to the indie explosion.

As with all markets, once something has been established, it continues to grow and create capital. Indie development is no exception. Despite not having the support of publishers, indie developers are able to survive because of the scope of their games, another contribution to the indie explosion. Scott Steinberg, managing director of Embassy Multimedia Consultants described this in gaming magazine Electronic Gaming Monthly when he said "games designed for electronic distribution can be built for under $150,000 by six guys sitting in a garage. This means: A) Developers/publishers can finally afford to take more risks; B) Originality does not have to bow to marketability; and C) Amusements needn't be all-consuming" (Steinberg 22). With this reduced scale, economic return isn't as crucial to an indie developer as it is for AAA development. Feeding six guys in a garage is easier to accomplishable than feeding a team of 100+ individuals. This allows for indies to stay in the market with less funds for themselves, and allows them to keep prices low for consumers. With both of these combined, indie gaming continues to be on the rise and allows for more and more creative individuals to go indie, with more consumers focusing on them.

However, this small scope doesn't automatically equate indie gaming to some niche market that only attracts a small portion of consumers. This is evident in the capital generated by indie gaming. Jason Ankeny, executive editor of FierceMobileContent confirms this is an article with Entrepreneur when he states "North American mobile gaming revenue will surpass $1.2 billion [in 2012], exploding from $462 million just five years ago" (Ankeny 36). Given that this figure is confined to only iPhone users, and North American ones at that, the number is rather staggering. With a tiny corner of direct download games encumbering $1.2 billion dollars, it's easy to see how indie games are a legitimate aspect of the gaming market, and not some microscopic element that has a few rabid followers.

Not only is it evident that digital distribution is a legitimate part of the gaming market, but it has spawned, and will continue to spawn, its own market. Although indie developers don't have a publisher to take a portion of their profits, that doesn't mean they get all of the money their games generate. Corporations that host digital distribution take a percent, usually 30, of every digital sale. This extends beyond the gaming industry, and is seen in music, ebooks, and film. With this in mind, various corporations are offering different distribution methods for the same media, and this pattern has been demonstrated in the gaming industry.

This is most evident in the computer market, with Valve's Steam, EA's Origin, and Ubisoft's Uplay. Although digital distribution is still fairly young, it's safe to say that competitors will arise to challenge the already established corporations. Eric Savitz, a writer for Forbes magazine, explains this when he states "just as a strong field of players emerged in the video streaming field following the success of Netflix, we're seeing the same pattern in game distribution. Many companies hope to replicate Valve's success. EA thinks it can surpass Steam, and be the Facebook to Steam's MySpace" (Savitz 2). With digital distribution as prevalent as it is, there is clear profit to be made. With the potential for massive income, other companies are simply trying to get into this market, and earn capital for themselves.

Despite these numbers and the finances of indie gaming, AAA games still dominate the market. These games are bigger in every sense, from team size, to dev cycle, to number of hours necessary to complete the game. Given this, they take in more money than indie games. This is seen in popular first person shooter Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3. Andre Marchand of The University of Muenster and Thorsten Hennig-Thurau of City University London confirm this when they state "When the video game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 was released on November 8, 2011, it earned $400 million within 24 hours in North America and the United Kingdom (Activision 2011). After 16 days, its revenues had passed $1 billion (Waugh 2011)" (Marchand and Hennig-Thurau 1). This is one highly successful game, and an outlier when compared to other AAA titles. However, this one game made almost as much money in 16 days as the North American iPhone market made five years. Indies are successful, and will continue to be successful, but AAA games will always be the big hitters of the industry, as demonstrated by the prevalence of this particular Call of Duty game.

Bundling as an Economic Platform:

As the scope of AAA games becomes larger and larger, more and more developers find themselves going indie. However, the struggle for indies to be heard in comparison to both the AAA market and previously established indie titles is real. Given the explosion of the internet and direct distribution, various companies have begun selling bundled games as their entire platform, such as widely popular Humble Bundle. In this regard, these companies have become their own distribution methods, similar to the Origin, Uplay, Steam triangle, yet operate independently of these above mentioned mediums. As a result, the games that are sold in video game bundles are readily available in several different methods, thus making them mixed commodity bundles.

As with other distribution methods for other media, the competition between bundling companies is very steep, and each of these companies needs to generate some edge over their competition. With this need for an edge, two distinct occurrences have arisen in game bundling. The first of these is a leaning towards indie titles, with the vast majority of game bundles being exclusively indie titles. The second occurrence, and the one where the chief disagreement over the benefit of bundling in the gaming industry lies, is the ability for consumers to name their own price for these game bundles.

Several gaming bundles operate under this name your own price platform, where consumers are given product regardless of how much or how little they pay. There are certain incentives to pay more, such as locked games that are only unlocked if you pay higher than the average, but the general rule of thumb is consumers get games regardless of what price they set for themselves. As a result, there is a common thought in the game industry that bundles are creating a 'race to the bottom,' or the ideal that because of bundling, games will be worth less and less money over time. This is the chief argument against bundling in the gaming industry.

This argument is completely true. In gaming, and all markets really, there is the idea of the deep discount, which is a clearance esque price point. The argument against bundling is that this name your own price platform has become the new deep discount in the gaming industry. This is so because consumers generally behave as you would expect them to; giving the absolute minimum amount of money they can. Alex Ting, a business developer for Humble Bundle, confirms this in an interview when he states "If I say… 'you can pay what you want' that guy is gonna pay me a penny, or that guy is gonna pay me a dollar for Steam keys. That guy is gonna pay me just a penny over average, because he has no incentive, she has no incentive, to pay very much [for the locked titles]" (Ting 4). Here, Ting clearly indicates a trend that is occurring in bundles, with bundling driving the prices of games further and further downward. Given the pricing structure of bundling, there should be no surprise that this is occurring, as consumers will always prefer more products for cheaper prices.

Trolling through the history of Humble Bundle purchases further exemplifies this ideology of scooping up products for the minimum amount of money possible. Despite these bundles usually containing several games with a combined value of over one hundred dollars, the total average for all bundles only comes out to $6.71, which is clearly a lesser value than these bundles are worth ("Prior Bundle Statistics"). With these statistics, the race to the bottom is clearly demonstrated, and provides a strong argument to both why bundling is bad for the industry, and how bundling devalues a game. Value is really the buzzword in this entire equation. Games carry an economic value to them because they are a product which consumers use. As with any product, the question of actual versus perceived value comes into play when discussing gaming bundles. With this in mind, it's important to understand the trend that is occurring with name your own price. The established trend is that bundles are lowering the perceived value of the games sold in that bundle.

This is highly significant because it has been established that a lower actual value has a positive correlation with a lower perceived value. In short, consumers expect more when they pay more, and expect less when they pay less. This is most evident in the world of wine, where higher priced wines are commonly more appreciated than lower priced wines. Robin Goldstein, food and wine critic, explains this when he writes "a number of studies have reported positive correlations between price and subjective appreciation of a wine for wine experts" and then later finds "a non-negative relationship between price and overall rating for experts" (Goldstein et al. 2, 5). This is crucial to understand because it sets the precedent that consumers who purchase a bundle at lower than the bundle cost believe the games to be worth less than their actual value. When this occurs, these consumers are expecting less from these games than if there were bought at full price.

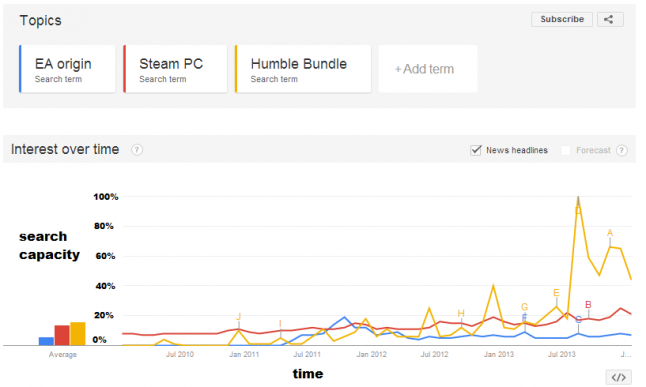

The capitalist precedent has already been set that what is favorable in the market stays and what isn't favorable in the market goes. In this regard, it would seen that bundling shouldn't be as prevalent as it is, based on these negative effects. However, bundling is clearly a large part of the industry, and doesn't seem to be going anywhere anytime soon. This is confirmed by Google Trends in figure 2, where the interest in Humble Bundle has shot far beyond Steam and EA Origin. With this interest clearly evident, the question remains as to why exactly bundling is a positive platform in the gaming industry, when all indications of the name your own price model demonstrate a lower value to the game.

Figure 2. Interest in Humble Bundle over time as compared to other direct distribution methods

First off, as previously demonstrated, mixed commodity bundles generate more funds for the company participating than pure components pricing, pure bundles, or price discrimination. So despite the name your own price element, bundling is a better alternative to simply selling your game. Aaron San Filippo, designer of popular indie game Race The Sun confirms this via interview, saying "the bundle itself was great, generating tens of thousands of dollars in revenue that we probably wouldn’t have seen without it" (Filippo 1). Ultimately the chief goal of running a company is to increase your profits and make your company worth more money. Despite the deep discount nature of the game bundling platform, Filippo had a positive experience with said platform and generated funds for his company.

He is not the only one who experienced such success. Several other indie developers have mentioned the economic benefits they have experienced as bundle participants. Ryan Wiemeyer, owner and designer for Chicago based indie team The Men Who Wear Many Hats, had a similar experience with Humble Bundle. Ryan explains on his blog, stating " We did the Humble Bundle which got us 177k sales but those were at about $0.39 a copy. We don’t feel bad about that since the game has been out for so long and many of those people probably wouldn’t picked it up otherwise" (Wiemeyer 1). Despite the low price point for the game, participating in the Humble Bundle netted Ryan and the Hats team approximately $70,000. This figure may seem low, but it's important to recognize that this figure was split amongst a company with two permanent members. More importantly, it is very doubtful that this money would be collected in any other instance, thus making it an economic gain that wouldn't otherwise have been matched.

Bundling and Popularity:

This marketing aspect of game bundling is one of the main reasons these bundles are a positive force in the gaming industry, particularly to indie developers. With these bundles, indie developers are essentially able to spark interest in their game for free. Ian Bogost, game designer, writer, and professor at Georgia Tech, emphasizes this when he states,

game bundles reduce the unit cost of games, and is it's impossible to deny that they are contributing to the 'race to the bottom' in media pricing more generally. But because each bundle or sale only lasts a limited time, it exerts a different force, offering certain sell- through for one, but increasing potential reach thanks to the surrounding publicity. In that respect, bundles are also promotional campaigns in which a temporary reduction in price with a particularly desirable placement results in free marketing with considerable reach -- while also delivering substantial revenue thanks to volume. Bundles are the retail end caps of the indie gaming supermarket. (Bogost 3).

Here Bogost demonstrates that despite the decreased economic value in a game bundle, the non economic benefits of bundling far outweighs the decreased value these games are placed at. Bundling creates economic revenue despite this decrease, but the increased traffic these games see is arguably more important.

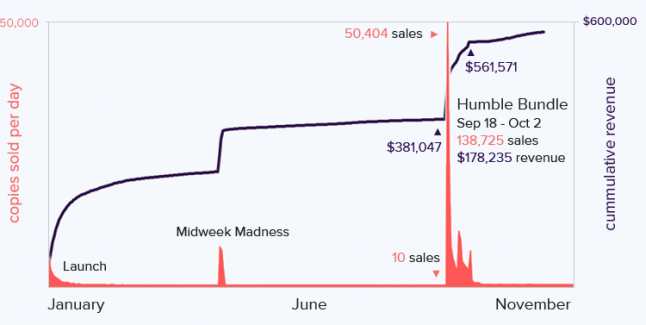

The indie market is completely swamped with titles. Because indie games are smaller in scope than AAA titles, they are arguably easier to produce, and as such, there are more of them on the market. This in turn creates an intense power struggle for indie games to be noticed in the flooded market, and sell their game. With this competition, the typical lifecycle of a game occurs in peaks, where traffic on the game comes about in the form of sales once the hype of initial release has died down. The typical lifecycle of an indie game can be seen with the Hitbox Team and their game DustForce in Figure 3. This chart clearly shows the jumps in units sold that occurred through various sales, discounts, and events; including the Humble Bundle.

Figure 3: Sales of Dustforce over time

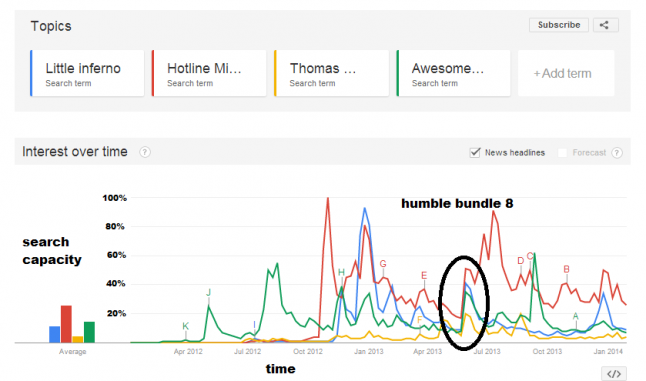

Again, with the experience between Filippo and Wiemeyer, DustForce is not an independent example of the traffic in the indie gaming scene. Figure 4 demonstrates this beautifully. In this chart, four separate games are tracked with their interest over time. Although they all have a haphazard interest level over time, all four of these games receive an intense hike in traffic at the same time, and this hike in traffic is because of their participation in the Humble Bundle 8. This increase in traffic further demonstrates the race to the bottom ideal. These games are all being discounted, and with a name your own price bundle, it is a deep discount. However, looking at the DustForce sales charts, as well as the Humble Bundle 8 traffic, the increase in game popularity and discussion far outweighs the decrease in value per unit, especially since most of these titles go into these bundles well after the game has been released.

Figure 4: Interest over time with Thomas Was Alone, AwesomeNauts, Little Inferno, and Hotline Miami

Although the name your own price method clearly indicates the race to the bottom, it is important to also understand that the name your own price method does offer outliers on the opposite end of the spectrum. Ian Bogost notes this when he writes "while the average purchase price for the Humble Indie Bundle #4 was $5.45, or a paltry 61¢ on average per game or charity, the highest price paid was $8542, by MineCraft creator Markus Persson" (Bogost 4). Bogost also notes that Persson was the second highest contributor, but discredited the @HumbleBrony Bundle's massive $16,005.27 figure on the grounds that it was a collective pool of money collected through crowdfunding and going towards charity ("Prior Bundle Statistics"). Although Alex Ting warns in an interview " There are so many people buying a bundle at a penny hands over fist, than anyone contributing at anywhere close to the average, above or at average" that doesn't mean these contributions don't happen, nor should they be overlooked or discredited (Ting 8).

Games as an Art Form:

Despite the cuts to a games economic value, the experience of bundling is still clearly beneficial. But games are also a distinct art form, and as such, they carry a value that goes far beyond economic. Previous mentions focused on the economic side of this dynamic, but looking beyond that and into the realm of a games non economic value is fascinating. Aaron San Filippo mentioned this in interview when he said "We intend to bring [Race The Sun] to more platforms, and we want as many people to be aware of the game as possible" (San Filippo 1). Here Aaron indicates that the decision to place his game into a bundle went well beyond the realm of basic economics. The desire to port to other platforms or consoles from another medium does not automatically guarantee success. With that in mind, the decision to put Race The Sun into a bundle was strategic, and not just some random thing Aaron and his team did. This indicates there is value in putting a game in a bundle beyond the economic.

This is one example of the non economic aspect of placing a game into a bundle, but the entire space of non economic benefits from bundling is challenging to navigate. This is so because the experience of playing a game is so personal, and so is the artistic and non economic value that experience brings. Examining how this value is effected by a bundle is a much harder gap to bridge, given that personal touch. When considering a game however, it is important to recognize that two forms of currency are placed into a game. The first currency is money, as these games are a consumer product. The second form of currency is time. Since games are an interactive experience, the hours that a consumer puts into playing the game is another direct representation of how much value that consumer places on the game.

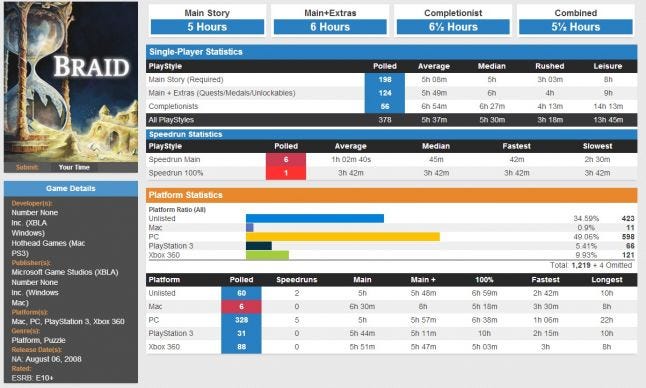

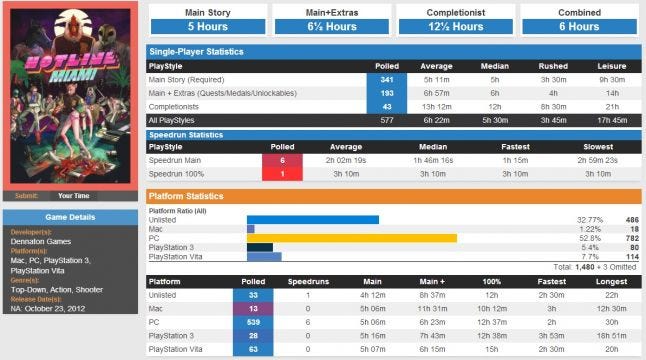

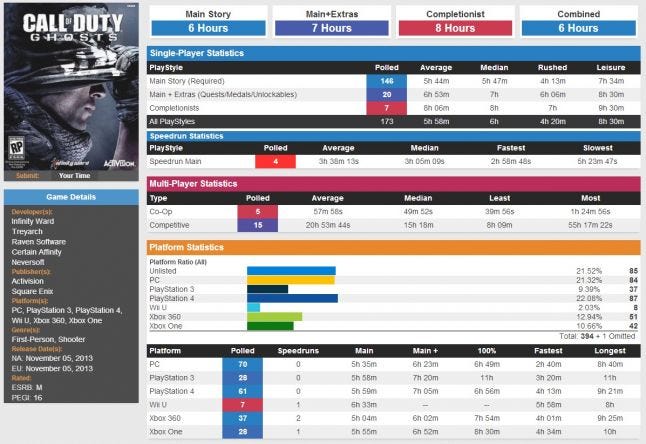

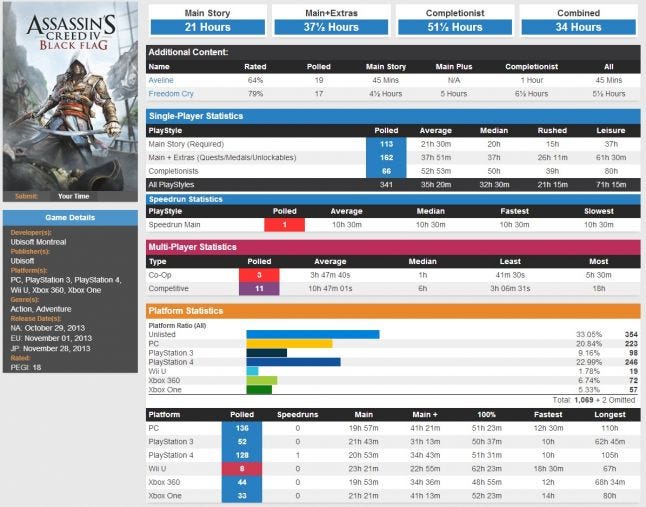

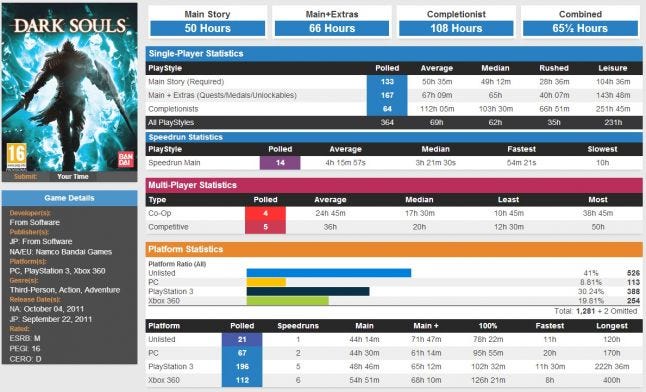

If a consumer values the experience of playing a game, they will repeatedly play it, and therefore, put more hours into the game. When looking at bundling in the gaming industry, play time across systems generates valuable data with regard to how popular indie games are. Using the resource HowLongToBeat.com, playtimes for games can be examined across systems. Figure 5 shows playtime across three popular indie titles, Braid, Bastion, and Hotline Miami. Figure 6 shows the same resource, only with popular AAA titles Call of Duty: Ghosts, Assassin's Creed: Black Flag, and Dark Souls. Looking at these two figures reveals several key points of data about this use of playtime.

Figure 5: Statistics for playtime on Braid, Bastion, and Hotline Miami

Figure 6: Statistics for playtime on Call of Duty: Ghosts, Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag, and Dark Souls

The first piece of data that is important to consider from this revelation is the simple nature of who plays what game. Every AAA game examined is played more frequently on consoles than on PC, and the opposite occurs with the indie titles. This indicates that the demographic of console gamers is more focused on AAA games than indie titles. On the flipside, the demographic of indie gamers is focused more on PC than console games. Additionally, the indie titles receive higher play time on PC than on consoles, and the AAA games received higher play time on consoles than on PC. Since the amount of play time invested in a game is the most significant measure of the playing experience, and following the old mantra 'time is money,' the argument can be made that the perceived value of an indie title is greater for PC gamers than console gamers, and the reverse trend occurs with AAA titles.

It is important to recognize that the perceived value for an indie PC game bought in a bundle is lower than the actual value, as demonstrated with wine critic, Robert Goldstein. This indicates that players also view the experience of playing the game as less significant. When you buy a game, you are buying the ability to play said game. With this in mind, by purchasing a game at a deep discount, the consumer is essentially saying that the experience of the game isn't worth as much as the developer claims it is and the consumer values the experience less. Although this is the consumer trend in the gaming industry based on the race to the bottom, it's crucial to note that the game experience doesn't change based on the price point. Placing a game in a bundle simply changes the popularity of the game, as seen with how much it is discussed, how present it is in the public eye, and how this presence changes with a gaming bundle.

The Future of Bundling in the Gaming Industry:

As with anything, the future of bundling in the gaming industry remains to be unforeseen. Alex Ting is fearful of this future, stating "I think bundles are going to fall out of novelty very soon [or] Humble Bundle is going to become a staple and pay what you want is going to become the new 90% off" (Ting 8). Although he is one individual, there is a ton of validity behind Alex's argument. Looking at the statistics for past bundles indicates that there is a progressive downward trend in the average value of a bundle. This coincides with Ting's idea that bundles are falling out of place ("Prior Bundle Statistics").

What's interesting to note in Ting's words is that he touched on the novelty of the bundle. Basically, Ting is stating that bundles will make money and therefore continue to stick around, but at the same point they don't have that special charm that they used to. Ting hopes to remedy this issue by bundling physical products with the game, similar to how a Kickstarter campaign results in unique products related to the Kickstarter project. He expressed this practice as a frontrunner on a Humble Weekly sale. During this sale, Ting organized a physical product that was included in the bundle at a price point. Ting said "with this [Humble Bundle] you get two physical swag boxes. Fangamer worked with their designers to come up with exclusive, unique, never to be sold again swag, for this bundle" (Ting 6). With this physical component, Ting was able to drive the sale of the bundle, and as such, increase its profit. As a result, the developers earned more money for their games, and Humble Bundle has begun exploring physical product bundles.

Others take a different approach. Aaron San Filippo is concerned with the price points of a game itself, but is considering alternatives to a physical bundle. Not only does he want the individual game sale to be prevalent in the market in conjunction with bundling, but he also wants to see the long term costs of a game remain high. He confirmed this in an interview by stating "People are still buying bundles, and the post-bundle sales don’t seem to be negatively affected, at least in the short term. In the long term, I’d like to think about how we can keep the value perception as high as possible for games" (San Filippo 1). Although Aaron takes a different approach to bundling and deep discounts than Alex, he still wants to drive consumer prices higher and reverse that race to the bottom trend in the future. This is easier said than done however, as the precedent has already been set.

Possibly the greatest remark on the experience of a bundle is professor Ian Bogost, when he writes "bundles are not just transparent storefronts through which indie developers enjoy fame and success; they are also poised to alter the ecology in which games get created and used" (Bogost 7). The first half of Bogost's quotation is fairly straightforward, but it is the second half that carries so much though provoking weight. Essentially, Bogost is saying that we don't know what the future of bundling in the gaming industry holds, we just know that it will continue to shape and effect this industry in monumental ways.

Although we don't fully know the future of bundling, this paper has indicated several behaviors we have seen, and can continue to expect. We know bundles drive the cost of a game down, and this is a fact that is incredibly difficult to dispute. However, developers are still clawing over each other to get their games in bundles. Ting confirms this when he describes the process of being featured in a Humble Bundle. Ting states "a developer says 'please we want to be in a bundle' and then we put them in a big list of hundreds of thousands of games that are great and offer something original… this list is very competitive and very difficult to get attention on " (Ting 2). The simple reason for this is simple. A bundle creates popularity for a game, and the platform of bundling offers superior economic return when compared to selling games individually.

Given this, if games are going to experience a deep discount, bundling a game is the best method of experiencing this deep discount. Furthermore, a bundle will drive traffic of a game skyward, something that all indie developers can benefit from. Therefore, despite the economic cuts a developer will experience, bundling is massively beneficial to indie developers and a practice that the industry should continue.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like