Substantial mechanical spoilers ahead.

Skyrim is a strange beast: it is a surprisingly easy game to break (as in, become overpowered). I say surprisingly because, once you get over the fact that there are only three character attributes, it becomes apparent that the leveling system in TESV is significantly tighter and—*gasp*—deeper than that of TESIV.

Admittedly, leveling in Oblivion wasn’t all that deep so much as it was tedious. It never really got further than just keeping an accurate count of all your skill level ups to maximize attribute gains per character level (well, that and making sure not to pick any skills you would ever actually use as your majors). Being a crazy weirdo, though, I found that obligatory meticulousness to be the most engaging and rewarding aspect of the entire experience.

So, despite coming in to the game with an initial skepticism (and even a bit of dismay), I was pleased to be convinced that Skyrim is one of the few, few games where streamlining is not just a euphemism for reduction towards shallower gameplay. Unlike most games that fail at streamlining by merely paring away existing features, Skyrim is much more of a fundamental redesign from the ground up.

Good Times

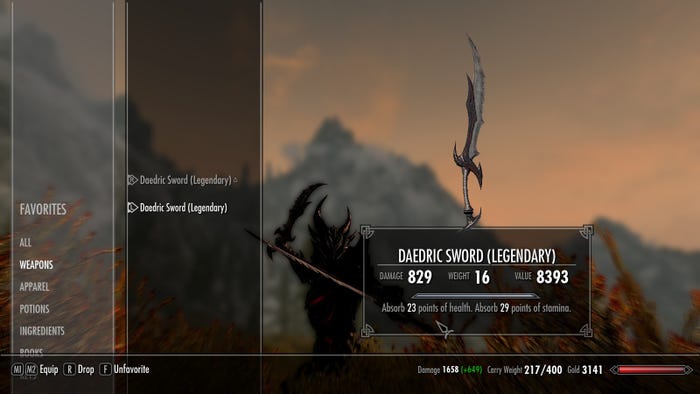

The focus and tension, however, loosens considerably around level 30 or so (or simply, once you max out enchanting and smithing—more on that later). And yet it remains a genuinely fun game to play even after arriving at build solutions that can render your character well-nigh invincible. Indeed, the fun of it lies in the very discovery of all the myriad ways to break the game.

Importantly, once you get bored of one solution, you can essentially start a “new game+” with renewed challenge in the same game by picking up a new, previously unused set of skills (just make sure you really need those perks before you spend points in them). And it is the very fact that certain mechanical possibilities are so overpowered that makes this possible.

The strangest thing about Skyrim, then, is that it achieves balance by frequently letting the player break it.

A large part of why this works lies in the open nature of the game. Being able to make ludic progress without having to make a narrative one has always been the advantage of open world games, but Skyrim takes this even further by letting you do boss fights whenever you want. In a way, it harkens back to maxing out your wanted level in GTA3 (and living to tell the tale), when it was still both enjoyable and profitable to cause random destruction.

No longer do you have to thanklessly re-trudge through a dungeon long gone stale to reach that nugget of fun: you can just fast travel to it directly and chain dragon fight after dragon fight after giant fight after giant fight. Plus, since all your top items are going to be self-crafted anyway, these engagements become about ludic performance (with maybe some bonus skill gains tossed in) and far less about grinding for loot—a test of player skill, not player patience.

The best part of this, of course, is that it allows you to stress test your character build whenever you want, and that sort of instant and tangible feedback is what makes breaking Skyrim so rewarding and engaging. It’s also what keeps the gameplay from becoming stale. Find something new, try it out, enjoy it for a while when it works, then move on to earning another new, shiny skill. Just sitting around thinking up novel ways to combine skills is silly fun.

The same character later as a sword & board damage sponge.

I want to be a bit more specific by what I mean when I say that certain mechanical possibilities being overpowered is what allows the player to try out new skill sets. For a particular example, let’s talk about crafting (this is where the mechanics discussion will get a little hairy).

The crafting skills are now robust enough to completely support the player on their own. This mainly has to do with two factors: 1. you can now fortify a magic school to reduce magicka cost to casting spells from that school to ZERO; 2. The damage reduction cap of 80% can be reached with a relatively low armor rating (567), while the master enchantment perk of two enchantments on an item lets you max out resistances too.

As an experiment, I decided to start a new game (master difficulty) to level only the crafting skills until I had maxed them out (good lord that used up all of Saturday). This took me to level 35, which would basically have resulted in an unplayable game in previous TES games. The suspicion, however, was that using enchantment to boost alchemy (loop that twice) to boost smithing would put me a stone’s throw away from hitting the damage reduction cap with the starting Heavy Armor skill level.

This suspicion was borne out with an AR of 447 at level 15 Heavy Armor with no perks, and sure enough, my character was quickly tanking giants and spamming restoration with aplomb.

The Holy Grail of Crafting

The fact that enchanting can now be done by non-spell casters (and that filled soul gems are sold by merchants) is a fairly huge deal, and shows how much the game has been redesigned. Most shockingly, magicka cost reduction buffs will also reduce cost to soul charged items. With max Fortify Destruction, your absorb health/magicka/stamina and elemental damage charges will never run out, while max Fortify Alteration will let you spam paralyze with every attack (heck, you can do both!), etc.

At any rate, what all this demonstrates is that having areas with set level ranges or difficulties is not the only thing that makes Skyrim’s scaling difficulty more genuine. Much thought has gone into how different skills and passive effects can relate to or make up for each other (as demonstrated by the ability to hit the damage reduction cap or spam magic by investing in crafting perks, etc.).

The end result is that the player is much less likely to be punished for not knowing what skills to keep up, while players who already know (or spent perks carefully) are significantly rewarded with hilarious amounts of agency. And the game is well-tuned enough that it rarely feels like the player has agency that wasn’t earned through effort or discovery.

The great fun of Skyrim, then, is that it convincingly manages to be po-faced and secretly outrageous at the same time. I’ve hit level 50 nearly twice now, and the absurd/black humor of shield charge or snapping to first person for a dual gut stab finishing animation still hasn’t gotten old.

Since I was spending so much time playing Skyrim, a friend of mine who had never tried any of the Elder Scrolls games asked me to describe what kind of game it was. The inevitable question came up: does it have multiplayer? Once he heard the answer, his interest flagged, and I lamely attempted to discuss how single player games can achieve deeper experiences of a kind that can’t really be pursued in multiplayer games (all I could come up with at that moment was “by going deeper”).

Actually thinking that through though, there is a genuine and tangible reason: single player games can go deeper by not having to worry or care about if the player is playing fair. The cap on earned player agency can therefore be significantly higher, making it more likely that the limits of player skill are set by the player himself, and not arbitrarily by the game to achieve balance and parity. These are games that can be solved, and it’s hard to overstate how important it is that the player can repeatedly work on improving very specific aspects of his game.

And Skyrim, with its immediate feedback implementations, does this beautifully well. It’s a game that tangibly rewards experimental investment and knowledge discovery, and it's one of the most engaging ludic experiences in recent memory.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like