I played a mobile game over the weekend that single-handedly changed the way I think about text-based adventure games. That game was 80 Days from Inkle Studios, a non-linear story that contains more than half a million words in total.

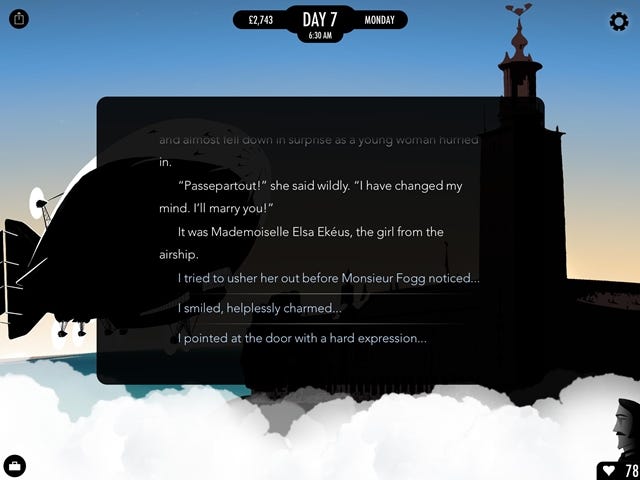

I played a mobile game over the weekend that single-handedly changed the way I think about text-based adventure games. That game was 80 Days from Inkle Studios, a non-linear story that contains more than half a million words in total. You play out the story of Phileas Fogg's trip around the world in 80 days, from the perspective of his French valet Passepartout. You choose the path around the world, the cities you stop in, the modes of transport, and the various twists and turns that the tale takes. Jon Ingold, creative director at Inkle, describes 80 Days as "A self-narrating boardgame - it's like Monopoly, but as though when you bought a hotel somewhere, you actually went to buy a hotel, decided on what it looked like, and then argued with the new concierge." 80 Days is a seriously text-heavy adventure, which makes my love for it rather strange. While I do enjoy narrative-driven games, I regularly find myself put off by those adventures which are essentially walls of text with bits of game thrown in. Why, then, has 80 Days hooked me to the point that I'm about to start my fourth playthrough? Ingold believes that there is one key factor that has helped 80 Days strike a chord.

"It's like Monopoly, but you actually went to buy a hotel, decided on what it looked like, and then argued with the new concierge."

"I think the thing we've done, which not many other games have really thought about, is worked out the pacing of the text," he reasons. "While people always describe our stuff as a 'gamebook' - and of course Sorcery! was adapted from one - my personal background was in writing parser-based text adventures, which have a completely different rhythm to them, and one that's much closer to what we do." So rather than throwing walls of text at the player with the occasional choice, much like a physical gamebook might, Inkle has attempted to put the "beat of the story" in the hands of the play. The player is in charge of this story -- not the author. "The pattern is much more conversational: you say something, the game says something back, then you say something, and so forth," adds Ingold. "That pattern helps players feel like they have agency and they're being listened to by the game; it helps make the game look visually less intimidating - people definitely see text before they read it. And it has a collaborative feel: when it works well, it generates a rapport between player and game, with each building on the other's input." Shorter bursts of collaborative story also lend themselves better to building tension, notes the dev.

"You take a risky step forward, but you don't see what happens immediately: you have to take another, and another," he says. "So instead of choices like 'Avoid the man near the cliff-edge, or pull the guy back,' we tend to write a sequence of choices: 'Approach the guy. Go a bit closer. Talk to him. Go a bit closer still,' and so forth." "That's the same pattern as you get in a game of Blackjack: you keep getting another card, but with every card you get, the same choice is now made riskier." As you'd expect, balancing 80 Days such that players feel like London is always reachable in the alloted time yet so far away, was quite the challenge for the Inkle team, and the design was iterated on heavily for many month. Yet they managed it -- in fact, the mean completion time across all players is 75 days. Initial design felt rather disjointed, with the story getting in the way of the travelling, or the travelling itself feeling like a chore. This iteration led to the relevation that the story elements should exist to flesh out the game elements, rather than the gameplay existing to spread the story out. "The end result feels quite special for it," reasons Ingold. "There are these chunks of story you might only catch because you went a certain way, or even did something at a certain time. Fleeting, fascinating moments, that feel precious because you snatched them from the air."

"I think the thing we've done, which not many other games have really thought about, is worked out the pacing of the text."

80 Days is a mobile title, and while it definitely benefits from the pick-up-and-play factor, I found myself wondering exactly why it is that mobile feels like the perfect platform for this sort of experience. Says Ingold, there are numerous reasons he believes mobile is good for text adventures -- the small screen stops players feeling overwhelmed by text, while a touch-to-continue mechanic "makes it feel like you are drawing the game out of the glass yourself." "But I think the strongest reason - which is a bit woolly, but I think it's true - is in that we relate to devices differently than we do to computers," he continues. "When I turn on a PC I'm intending to do something; it's a terminal and I am the operator. I use the machine, and control it." "But if you watch people with phones, they pull them out of their pocket and check to see if the phone has anything for them. A tweet, a message, a text, a photo, whatever... We look to our phones to supply us with input. And our games exploit that." Playing 80 Days on a mobile, he reasons, has the same feel as swiping to check your Twitter feed on your phone -- that is, if your Twitter feed constantly had something for you to check.

"I think people are a lot more willing to immerse themselves into 80 Days on mobile because they start with the expectation that they will be entertained, and not that they'll be entirely in control," Ingold adds. "On PC, it would still work, but I think we'd have more people finding that the choices felt limited, and a lot more skim-reading." Let's say you're a developer reading this, and you've convinced yourself that text-heavy adventures are something you want to have a crack at. How long does this kind of game take to put together? 80 Days took around eight months to build, with three people working on it: Joseph Humfrey on the coding and art, Meg Jayanth researching for the story and the writing, and Ingold coding, writing and editing the script. "I think Meg probably spent a few hundred hours on research, not just into the time-period in each country in the world, but also into methods of transportation and inventions around at the time," Ingold suggests. "Most of our steampunk elements are derived from something real, or something hypothesised at the time. (Jaume, our illustrator, did even more research for his drawings - I have no idea how much! - and for the city art, we uncovered buildings and landmarks for every city in the world from 1872, which took an unreasonably long time.)" And that's just the research and the art -- the scriptwriting itself took the bulk of the time, with over 500,000 words making up the script for 80 Days.

"When I see the single one-star App Store review that says 'this is boring!' I can't help thinking, phew, someone noticed."

"While writing branching content isn't quite the same as writing a long novel - it's quite episodic and broken up into bits, and the branchiness means you're often writing alternatives for a line of dialogue or a description - it was still a pretty terrifying amount of work," muses Ingold. "I think when we started we had the sense there might be forty or fifty cities in the game, but everything kept on scaling up and up, with every new city meaning two or three new journeys to link it into the graph, as well as new art... Towards the end, Meg and I had a list of thirty or forty journeys that needed writing, and would basically have to lock ourselves in with alcohol and scream until they got written. Hopefully, players can't tell which ones they are!" Ingold says that it's important to note that these sorts of text-based adventures are quite a risk, since they aren't exactly the greatest marketable pitch. "One of the things we found working on 80 Days was there wasn't really a template to follow," he adds. "It's not really a board-game, it's not a resource-management game like Out There, it's not a gamebook - though it borrows from all three." "So we spent a huge amount of time trying ideas, dissecting their problems, building new alternatives. Our earlier versions of the game didn't have a clock, for instance, but simply tracked progress in days, but the result was quite static; and initially exploring a city was automatic on arriving, but that made the game feel too stage-managed. The ad-hoc, several-moving-parts nature of the final game was something that only emerged quite slowly and played hell with our script logic." With all this to juggle -- text, travelling, so much information to bundle onto an iPhone screen -- the team still can't believe the game has been received so well. "Every time we see someone in the world pick the game up and remark on Twitter, 'Hey, this is quite good!' we still can't quite believe it," he says. "I think we all still worry that everyone's going to suddenly realise it's a game with lots of text in it." "When I see the single one-star App Store review that says 'this is boring!' I can't help thinking, phew, someone noticed."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like