What do we understand under narrative design? How is it different to game writing or game design? How and where can you start out in the discipline?

“Tell someone to do something, and you change their life – for a day;

tell someone a story and you change their life.”

―Nicholas Thomas Wright,

The New Testament and the People of God

Chapter 1: Prologue.

I want to start this series, which certainly shot out of scope quickly, by dedicating some paragraphs to the fundamental question: what in the world do we understand as "narrative design", and how does it differentiate from writing or other design specializations?

Stephen Dinehart beautifully describes an "emergent paradigm", expressing that "Many studios are aiming with different titles and terms, but the goal is to transplant the player into the video game by all means of his visual and aural faculties -- into a believable drama where he is actor. This is dramatic play; interactive drama that utilizes interaction, rather than description, to tell a story." (Dinehart, 2019)

Arrording to Susan O' Connor(2020), while narrative design can include more software expertise and is commonly closer to game design, both writing and ND find their core in storytelling. Meanwhile, Julien Charpentier, senior editorial narrative advisor at Ubisoft headquarters in Paris, directly compares his position to the one of a writer (Bourguenolle, 2021, para. 4)

Following Dineharts line of thought, the answer to our question is in fact not a definite one – it really depends on who is asked!

The diffuseness of the term becomes clear as evoked by Inari Bourguenolle in the Ubisoft interview, who describes the concept as only recently formalized and its scope as "still not fully defined today". On one hand she says that "Narrative design is both the content and the way this content is brought to the forefront", however equally correctly mentions that especially smaller studios often merge those responsabilities in one game designer role, as is the case for Florent Maurin, as well as observed by myself in several companies. (Bourguenolle, 2021, para. 1)

Ayesha Khan provides a deeper comparison in her 2019 GDC session:

"a game writer's primary responsibility is to promote the story that is told in the script they write. A narrative designer writes as well, but our primary job is getting the whole game to tell the same story. We help to create the story and then tell it together. Our most important storytelling tool is not the written word, we use the game's feature set to tell the story." (Khan, 2019)

Khan describes the concept of ludonarrative dissonance (Hocking, 2007), meaning the inconsistency between verbal and emotional narration, as "preventing the games story and player experience to contradict each other." (Khan, 2019)

In summary, it is the narrative designers responsability that all parts fit together. Narrative equals experience, and is told not only through text but through all parts of the medium - from the first sales pitch over art, music, and gameplay, to individual user stories. How is the game advertised? How does it look, feel, sound? What does the player tell about the game in a real-life environment?

As Khan concludes in her presentation, the skillset of a narrative designer should be highly interdisciplinary. The narrative designer has to "become the vision-keeper. The go-to person for any questions anyone has. Provide cheap ways to add narrative to the game, using the existing mechanics." (Khan, 2019)

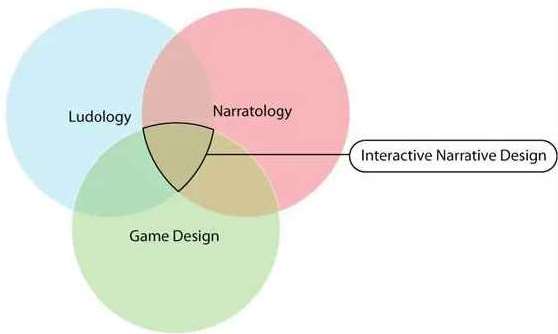

Catching up again from the first point, Dinehart describes dramatic play as "a paradigm that is the focus of interactive narrative design, a craft that meets at the apex of ludology and narratology and conjoins the theories into functional video game development methodologies" (Dinehart, 2019)

figure 1: Dinehart, S. (2019). Interactive Narrative Design. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/dramatic-play

Refering to the tools described by Khan as mechanics, Dinehart points out further definitions relevant to the next parts of this series: "Using these mechanics, the player acts as an agent within the participatory dramatic spectacle.

An agent is a person or thing that takes an active role.

The player moves forward through a series of events acting with designed mechanics to bring about change in the system in order to achieve some desired outcome.

To act is to cause or experience events.

An event is a transition from one state to another.

As a player acts he assembles a series of logical and chronologically related events, a fabula.

This is the story, a series of events cognitively assembled and perceived by the player. [...]

"A narrative text is a text in which an agent relates a story in a particular medium," [Bal 1994].

The video game is related, or narrated, by the video game engine to the player through both active and passive means." (Dinehart, 2019)

Dinehart further clarifies the synergy towards traditional explained by Khan(2019), writing that "while the aims of interactive narrative design are similar to game writing and game design, and surely involves many of their crafts, interactive narrative design makes story to take center stage so that the systems engaged by the player are delivered in continuity with a core thematic vision [Dinehart 2008]. " (Dinehart, 2019)

Agreeing with the previously discussed authors and speaker, Tynan Sylvester evokes the fact that, especially until recently, narrative roles in gaming have often had roots in the film industry. However, according to Sylvester,"film teaches us nothing of interactivity, choice, or present-tense experience. It has nothing to say about giving players the feeling of being wracked by a difficult decision. It is silent on how to handle a player who decides to do something different from what the writer intended. It has no concept to describe the players of The Sims writing real-life blogs about the daily unscripted adventures of their simulated families." (Sylvester, 2013)

Those notions will be revisited in further detail in other parts of the series, however are too complex for this introduction and would drive us too far away from Sylvesters initial point on the topic and into the actual narrative theory. Sylvester continues to draw a possibly closer comparition shifting the focus from film to interactive theatre play.

The concept of interactive play is gruesomely illustrated in the 2020 independent nordic-noir horror movie "Cadaver". In Cadaver, spectators are invited to a so-called interactive dinner spectacle, where the whole environment is used as a stage and the line between spectacle and reality is blurred as spectators progressively become themselves actors, in this case identity is diffuminated through the use of ball masks.

Another example of interactive story mentioned by Sylvester is that of living history museums – history is represented by actors to visitors who are able to explore at their own will and ask questions to the actors or even participate in historical recreations.

As Sylvester continues to gloomingly explain, ruins and graphities tell stories of the past open to the viewers interpretation, and "Even a crime scene could be considered a sort of natural interactive narrative to the detective who works out what happened—a story written in blood smears, shell casings, and shattered glass. " (Sylvester, 2013)

Interaction in narrative is not only limited to human creation, but is in fact a naturally ocurring phenomena. The author finally concludes referrencing Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey, which states that essentially anything is a narrative: "above it all, there are the stories of life".(Sylvester, 2013)

As previously mentioned, narrative design focuses on storytelling through every channel or mechanic rather than focusing on the word.

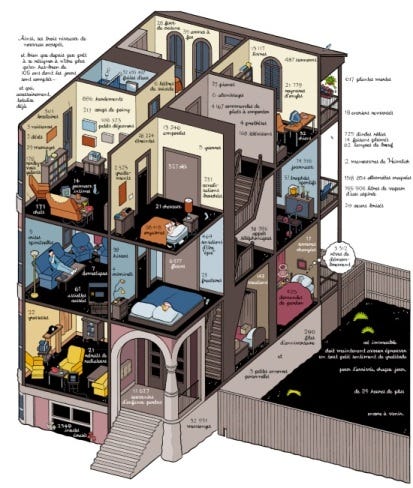

Figure 2: Ware, C. (2012). Building Stories. https://fr.kichka.com/2014/11/21/chris-ware-building-stories

To further illustrate this, we can draw a similarity to how architecture tells a story. Architect-cartoonist "Klaus" in his blog mentions exhibition and text by Chris Ware ""Architectural Narratives", which dealt with the varying relationships that architecture and graphic narratives have maintained throughout the years."(Toon, 2013)

According to Klaus, Chris Ware in his Building stories "challenges the reader with a non-linear, multi-faceted narrative, told from multiple points of view via a variety of different vehicles". (Toon, 2013)

"Architecture and narrative have walked hand in hand through history, crossing paths without really risking the extinction that the archdeacon of Notre-Dame gloomily predicted "

- Victor Hugo, Notre-Dame de Paris, 1831

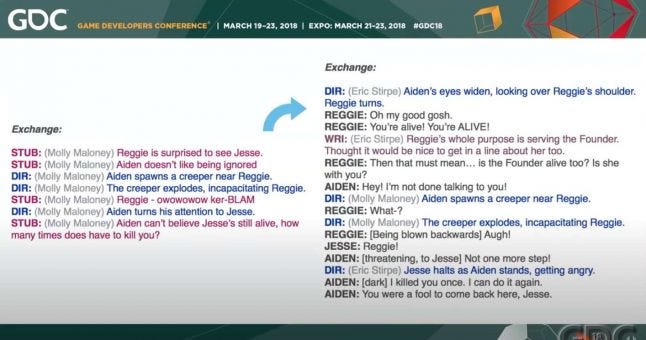

Designer Molly Maloney and writer Eric Stirp grant insight into this synergy with a more practical example on Minecraft Story Mode. They describe the practice of "stubbing", in which "design roughs in scenes first, like a blueprint." and "writing comes in after to write the dialogue over top." (Maloney, M., Stirpe, E., 2018). The pink text designates "stubs", which line out the underlying action, while literrary text from the writer are marked in blue:

figure 3: Maloney, M., Stirpe, E., (2018,03,19-23). Writing and Narrative Design: A Relationship[12]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FgBctI5ulU

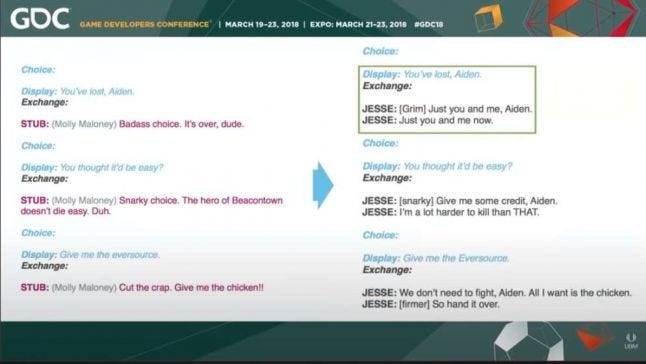

The filled-out text then comes back to design, where it is re-assessed, cut and eventually send to writing again for further iteration. Stirpe describes this as a "back and forth" allowing to "really enhance the process."

figure 4: Maloney, M., Stirpe, E., (2018,03,19-23). Writing and Narrative Design: A Relationship[12]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FgBctI5ulU

To conclude, while both game writer and narrative designer have a closely related center in the role of storyteller, they differentiate in their toolkits: a writer expresses his/her art through the written word, while a narrative designer also puts importance in writing but at the same time serves the structural, technical, and managerial role of coordinating, communicating, prototyping, organizing, and so on, therefore, as the title suggests, is much closer to other design disciplines. Narrative designer furthermore often come from very varied background, as it is the case with Khan and the experts interviewed by Ubisoft News. Throughout this article series, I will discuss aspects of both disciplines interchangeably, since more often than not the same theory finds application in multiple fields, although I will do so exclusively in regards to relevance for the designer.

Next parts:

Part 2: Setting and Tools

Part 3: Freedom of Choice

Part 4: Structure and Devices

Part 5: Character Design

Part 6: Time and Space

Part 7: From Theory to Practice

References

Dinehart, S. (2019). Dramatic Play. Game Developer. https://www.gamedeveloper.com/design/dramatic-play

O'Connor, S. (2020). Game writer versus narrative designer: FIGHT!. Susan O'Connor Writer. https://www.susanoconnorwriter.com/blog/game-writer-narrative-designer-jobs

Manileve, V. (2021). What is Narrative Design?. https://news.ubisoft.com/en-us/article/7m412GLSbfkaT0YheRYLVG/what-is-narrative-design

Maloney, M., Stirpe, E. (2018,03,19-23). Writing and Narrative Design: A Relationship[12]. Game Developers Conference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8FgBctI5ulU

Khan, A. (2019, 03, 18-22). Plunge into Storytelling: Transitioning into Narrative Design from Other Disciplines. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BV41WqouRrc

Klaus Toon, (2013), A New Book Yesterday: NEW RELEASE!: MAS Context: NARRATIVE

https://klaustoon.wordpress.com/2013/12/17/a-new-book-yesterday-new-release-mas-context-narrative/

Sylvester, T. (2013). Designing Games. O'Reilly. https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/designing-games/9781449338015/ch04.html

Herdal, J. (Director). (2020). Cadaver[Film]. Motion Blur: SF Studios. https://www.netflix.com/de/title/81203335?

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like