'It would be easy to make myself look cool in a game about myself, but that's not my goal,' says Nina Freeman. 'I want to be honest, which doesn't always make me look cool in the game story.'

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

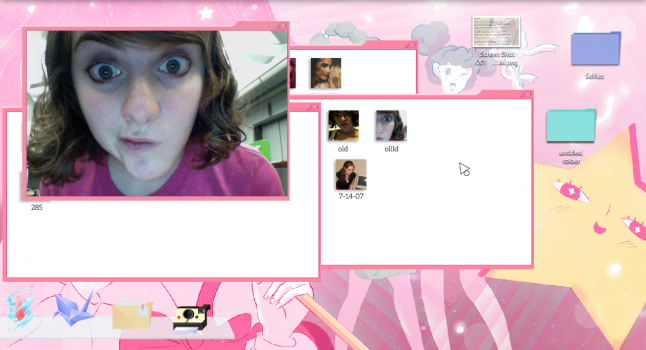

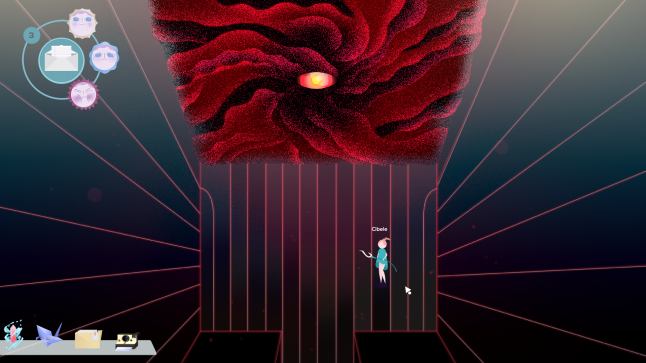

Star Maid Games' Cibele is an intimate, honest, and revealing account of young love in the early 21st century. Designer Nina Freeman based the game on an actual experience from her own life, when a romance that blossomed in an online MMO crossed over into an IRL encounter. The euphoria (and awkwardness) unfold from a first-person perspective--we see the romance blossom as if we're seeing it through Nina's eyes, in both a game-within-the-game and in the form of emails and journal entries and images on her computer desktop.

Cibele has garnered an IGF nomination in the Nuovo category. It was also an IndieCade selection, and was nominated in the Games For Change category of the Game Wards 2015.

Freeman answered some of our questions about the game. So did Decky Coss, who handled music, and Emmett Butler, who dealt with programming.

What's your background in making games?

Freeman: Cibele was made by myself and a small team--we call ourselves Star Maid Games. I am the designer and project lead on the game. Before I started making games, I studied poetry. So, as a game writer and designer, my skills are heavily influenced by my background in poetry. I'm interested in making games about ordinary lives, and tend to focus on vignette style character portraits. That is the kind of poetry I wrote and studied, so I carried that focus into my games work. I met the rest of the Star Maid Games team--Rebekka, Decky, Emmett and Sam, while I was living in NYC.

Coss: The first videogame I worked on was made at the 2011 Global Game Jam. Like Emmett, I was studying music technology at NYU with a focus on computer programming. The theme of the jam was "extinction", so I did music and level design for a puzzle game about killing plants. After that I did a few more game jams, took classes at the NYU Game Center, learned Sega Genesis programming, and branched out into tabletop with a game called Kulak.

Butler: I started making games when I was in school at NYU for computer science. For me, making games has always been a way to explore new technical challenges. The first game I shipped was called Heads Up! Hot Dogs that I worked on with Diego Garcia. It was about putting hot dogs on pedestrians. I've done a bunch of game jams and made a point of polishing each game to the point where we feel comfortable releasing it. Cibele became the longest-term project I've ever worked on.

What development tools were used to build Cibele?

Coss: I composed, recorded, and mixed the soundtrack using Renoise, Reaper, various VST instruments (primarily those by Native Instruments and EastWest / Quantum Leap), and a Yamaha DX7.

Butler: We used Actionscript 3 with Adam Atomic's Flixel framework and the Adobe Flex SDK. All of the development on Cibele was done using custom build scripts based on the existing build tools in Flex. I also built a bunch of specialized tools for things like map editing and asset generation. Despite how hard I tried to hack Flex into running on Linux, most of the core development on Cibele was done on OS X and shared via git.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

Freeman: It started as a prototype I made in a class taught by Bennett Foddy when I was in graduate school. After the initial prototype was done, I decided to continue to work on the idea with a team. A few months later I gathered the folks who would make up Star Maid Games. We worked on Cibele together for about a year and a half.

How long have you been thinking about making this episode from your life into a game? Did you have a clear sense of what the game would be like at the outset, or did it go through a lot of forms?

Freeman: Cibele is based on this time that I met up with a guy I had a relationship, who I met in Final Fantasy Online. This happened back in 2008. So, it's been quite a few years since then. I always thought that that experience had left a big impact on me, and that it made for an interesting story. However, I needed to wait until I felt that I could write honestly about it. I needed critical distance. When I decide to use a personal story as the source for a game story, I make sure that I have enough critical distance from the experience so that I can write clearly and honestly about it. It would be easy to make myself look cool in a game about myself, but that's not my goal--I want to be honest, which doesn't always make me look cool in the game story, but it makes for a more interesting character. Having critical distance from the experience helps a lot with that.

What has the response to the game been like? Are there things that people are telling you they found in the game or got out of the game that are surprising or unexpected?

Freeman: The response has been very positive. I have had a surprising amount of people reach out to me directly, because they felt a personal connection with the story, or related in some way. Most of them have told me a personal story of their own, of a similar relationship, or an online romance. Making games about ordinary life stuff, like relationships, often elicits this kind of feedback in my experience. People really like to see characters that they can relate to, especially when those characters feel honest, or like someone they might run into in real life. It's really encouraging to get this kind of feedback, as someone who wants to tell human, real world stories.

Cibele is a wonderful look at how young people interacted with each other online in a specific time period. Can you tell us about recreating the different elements of that online life?

Freeman: The details about Nina's life, the nuances of her conversations, and the specific ways in which this relationship escalated into sex, are what the game is designed to focus on and communicate. The mechanics are very minimal, and are designed to support and contextualize the story. The game has very little to distract the player from focusing on Nina and Blake's relationship as it unfolds. This was a very deliberate design decision, because my goal was to make a game that helps players understand and perform as a character within the scope of a vignette. There's no space for distractions in a game like this, so the details that support the players understanding of the character they're playing as are given priority.

Butler: One aspect of this process I really enjoyed was thinking about how to get the AI-controlled Ichi avatar to behave as the avatar of a human player would. Our primary focus was that he should go after enemies aggressively, to the point of stealing some kills from the player. We also wanted to make him a bit erratic, moving quickly from target to target. Designing the state transitions leading to this behavior was probably the most unique technical challenge in Cibele's development, and I think we did a pretty good job.

Any general advice you'd offer to someone developing an autobiographical game, or a game based on a specific experience from their life? And are there any lessons you've learned from making Cibele that you think would be helpful to other indie devs?

Freeman: I think the first thing to consider is whether you are actually wanting to make an autobiographical game, or if you want to tell a story that's based on something you experienced. I don't consider Cibele to be strictly autobiographical. The story is based on a true experience I had, but that experience was much longer and full of things that didn't matter to telling this specific story. I wanted to focus on the specifics of how and why I met up with this guy. It was a big, complicated experience, but I think it would be pretty boring to try and explain every single thing that happened between us during that time. I had to filter out all of that extra stuff that is important to me as a person but is not important to telling this specific story. So I take these personal stories, like Cibele, and I put them through that storyteller filter, where I ask myself what the most important details are that will communicate this experience as clearly as possible. So, I think my approach to writing matches up less with autobiographical writing, and more with fiction writing.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

Freeman: My personal favorite is Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes. I play that with friends--it's really fun to play in a party setting. I recently worked on a local multiplayer game and have been thinking a lot about that kind of design, so it's really inspiring to see other people doing such interesting work within that space. I'm also really excited for people to get to play Zeke Virant's game Soft Body, which got some honorable mentions. I've seen that game a lot over the course of its development, and it's a really special, amazing game.

Coss: I love Undertale. I recorded a few covers of some pieces from the soundtrack.

Butler: I got to try Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes at Indiecade 2014, and now I'm obsessed with trying to master it. Beglitched is also a really interesting combination of common puzzle game elements.

Don't forget check out the rest of our Road to the IGF series right here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like