Gamasutra's Road to the IGF continues in this interview with developer Peter Curry about how Dinosaur Polo Club built Mini Metro from a jam game into a strikingly streamlined transit puzzle game.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

Some of my favorite games are those that make complex, overwhelming systems seem approachable. Surmountable. Fun, even.

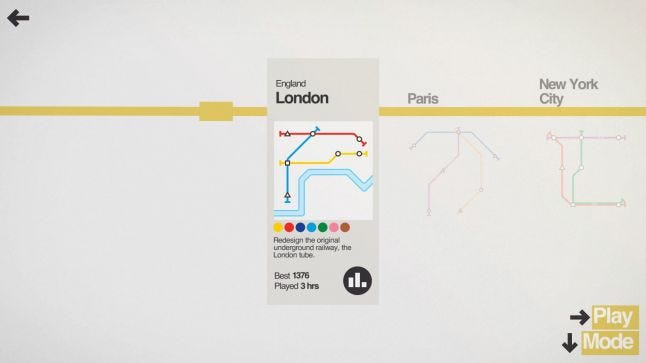

Mini Metro, released out of Early Access last year by Dinosaur Polo Club, does just that. What Cities: Skylines does for city management, what Spacechem does with chemistry, Mini Metro does with subway transit.

Forged in a 2013 game jam by Peter and Robert Curry -- the New Zealand twins who founded Dinosaur Polo Club together -- Mini Metro challenges players to manage the subway system of an expanding city, drawing new lines to connect stations and adding carriages to ensure that no station ever waits too long for a train.

It's a simple premise, deftly executed with striking minimalist art (reminiscent of transit maps around the world) and subtle soundwork by Rich "Disasterpeace" Vreeland. Mini Metro is nominated for a slew of IGF awards this year, including Excellence in Design, Audio, Visual Art, and the Seamus McNally Grand Prize.

Here, Dinosaur Polo Club's Peter Curry speaks to Gamasutra about how self-imposed contraints helped the twins create Mini Metro, the way it came together and how it seems to help foster more empathy for public transit workers.

What's your background in making games?

In 2001-2002, right after university, we {Peter and Robert Curry} both worked as programmers at Sidhe Interactive. Most of the games we worked on are only known in Australia and New Zealand (Rugby League, Rugby League 2, Melbourne Cup Challenge), but we also did some work on GripShift for the original PSP.

In 2006 we decided to try our hand at indie development, and started Wandering Monster Studios with another programmer at Sidhe, Lloyd Weehuizen. When that didn't work out (the usual story: unrealistic scope), we parted ways and went back to day jobs. That was back in 2008.

Neither of us had done any independent development since then, until I got the itch and conned Robert into it again.

So what development tools did you use to build Mini Metro?

We decided to develop our prototypes in Unity, mostly because we wanted the option to deploy to web. We figured that would be a huge advantage for a Ludum Dare entry!

We used Matt Rix's code-centric Futile framework. When Disasterpeace (Rich Vreeland) started work on the project we did some looking around at audio engines and settled on the G-Audio plugin for Unity, by Gregorio Zanon. It was the only tool we could find that gave him the level of control he was after.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

Far, far too long. By the time the IGF rolls around, it'll be coming up to three years! The game began as Mind the Gap, an entry into Ludum Dare 26 all the way back in April 2013. We started part-time development on Mini Metro straight afterwards.

It wasn't until March 2014 that I transitioned to full-time work on the game (Mary, my wife, took over as stay-at-home parent). We made the initial Early Access release in August 2014, and in November Robert quit his day job to come on full-time. In November 2015 we released Mini Metro out of Early Access, and since then have been splitting our time between support for the desktop build and work on the mobile build.

We hope to keep working on the game for a long while after release—our wishlist still has a ton of features and improvements on it!

How big is the Mini Metro team, all told, and how did you know when to expand?

There are four of us total on the team. Robert and I handle the game design and programming. Jamie Churchman, who we worked with at Sidhe, handles all the visual design and has contributed significantly to the game design as well. I don't think Disasterpeace needs any introduction—he of course handles the audio!

We always knew we'd need to get someone to work on the soundtrack. Neither of us know much about audio, but for Mini Metro we always had a vision for a procedural soundscape generated solely by events in the game.

Disasterpeace was the first person we approached, I figured it couldn't hurt to start at the top. I emailed him out of the blue (spent a long time crafting that email!) and was amazed when he not only replied, but was actually interested in working on the game. It's been amazing working with him. It's a real treat working with people who are very, very talented at what they do.

At first we were going to get away without a visual designer, but once the idea picked up traction we decided to bring an artist on board. We are so, so glad we did. Coder art is good and all, but looking back at the alpha builds ... yeeesh.

How did you come up with the concept?

To improve our odds of actually finishing and shipping a game, we set ourselves a number of strict constraints when coming up with ideas to prototype. The most important was minimal production art (we're both coders). That cut down our options to a handful.

One of the concepts that remained was one of Robert's, a subway navigation game. When he was visiting London he found planning the day's journey on the tube quite satisfying, and had suggested a game based on that. I suggested that having the player build the map, with AI agents navigating their way around it, might be more compelling than travelling on a fixed map.

Did the process of making this game change the way you look at cities and their transportation systems? Why or why not?

In short: no. It didn't take long for us to start thinking about the game in purely abstract terms, i.e., nodes and edges instead of stations and lines. Although when I look at a transit map I'll often study the graphic design and think about how difficult it would be for us to implement it Mini Metro.

Something we've heard from a ton of players is that Mini Metro gave them a sense of the difficulty of planning a public transit system. That the next time the train is running late, they'd be understanding instead of angry. That wasn't intentional, but I love that we've maybe added a little empathy into the world.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

Yes! I didn't end up playing many games at all throughout 2014; after work and family, I never found much time for it. I fell into the dangerous habit of relying on my Twitter feed, podcasts, and the occasional article to fill me in on the recent releases. Last year I made a concerted effort to play more games, and I've played a good chunk of the finalists.

I played through Her Story with Mary and we liked it a lot. Our third or fourth search term was picked out of the blue and gave us a 'late' video, so we had a different experience to most, but I love how it doesn't ruin the game. We just got a different narrative.

Every time we've shown Mini Metro at an event we've found ourselves next to Steel Crate Games. At PAX Prime Robert managed to talk them out of a key for Keep Talking & Nobody Explodes. We've had a blast (hur hur) with that game over the last few months.

Darkest Dungeon got one of my rare pledges on Kickstarter, and I've been dipping my toes in every month or so since it released on Early Access. It stresses me out too much to play it any other way! I've briefly played the stunningly beautiful Armello. At GCAP last year I managed to catch Ty Carey's talk on Armello's visual design. Amazing the amount of thought that went into it.

I haven't played Panoramical yet, but want to check it out before the IGF. I can't wait to try out Superhot. It's one of those rare concepts that instantly grabs you, fills your head with possibilities, and makes you wish you'd thought of it first.

Don't forget check out the rest of our Road to the IGF series right here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like