At Oculus Connect, the 20-year veteran of the space offered up the key points for making games, and talked about his team's experience developing I Expect You to Die.

I Expect You To Die is Schell Games' award-winning Oculus Rift game, and at the Oculus Connect event in Hollywood today, founder Jesse Schell delivered an impassioned speech about the key lessons his team has taken away about developing in VR. His career in making VR games stretches back to the original VR boom of the 1990s, so he knows what he's talking about.

For a more in-depth look at the development of I Expect You To Die, read Schell's in-depth postmortem here on Gamasutra; if you just want the lessons, and fast, read on.

Lesson 1: Motion sickness can be eliminated

Schell spent time explaining the mechanism of how motion sickness works in the human body, but here's his most important takeaway: "Once it turns on it takes a lot of time to turn it off." That means that you don't want to do it!

And no, "a little" motion sickness is not okay. "That's like saying that there's this really great sandwich that's so good, it's so delicious, but when you're eating it you get a little sick to your stomach -- and you feel that way for a long time afterwards." He compared motion sickness in VR with the "scarring food experience" many of us had in our childhoods where we can never eat a type of food again for our whole lives; "imagine that happens to your game."

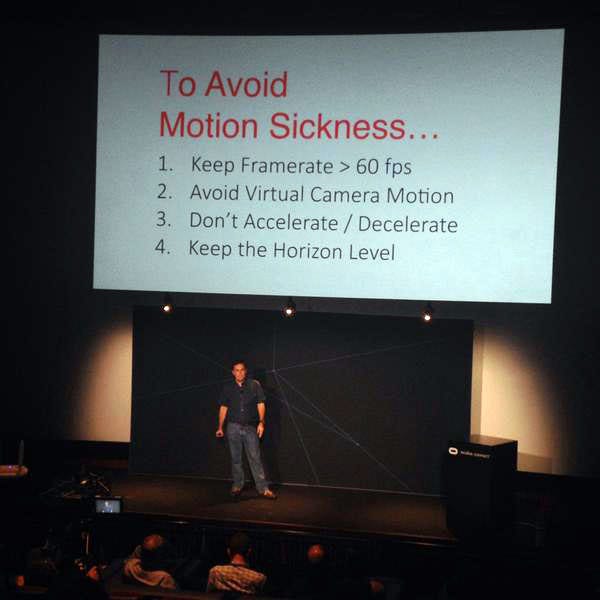

Here are his basic tips, in photo form, on how to eliminate it from your game:

Lesson 2: Design for the medium

Schell pointed out that when humans develop a new medium, they tend to adapt the old forms to the new. The classic example he used is that early films were stage plays. The problem is that doing this is "stupid, and it ends up looking stupid."

With VR, it's "better to skip the early imitation and just jump to the invention."

"When it comes to VR what's really different from what we had from video games is the sense of presence... enough feedback and enough signals that something deep in the back of your brain is buying into the illusion," Schell said. He pointed out that this has always been the crux of the appeal of VR, and "is the most important thing" about the medium.

Lesson 3: Immersion > gameplay

"As game developers we generally believe gameplay is the most important thing," Schell said. "But when you're in VR, I believe presence and immersion is much more important."

This presents a challenge, though, he said, because "the sense thing... is a fragile beautiful soap bubble."

"It's really tough to get it going," he said, and "everything in the universe wants to destroy it." As a VR developer, said Schell, "your job is to keep stuff out of its way."

Sure, you can say that gameplay is the most important thing, but "if your gameplay is popping that bubble, what are you doing?"

I Expect You to Die is a comedy-based game, rather than a fully realistic one; and that's because "comedy protects immersion," Schell said. "In a comedy world a lot of weird things can happen, and it's more tolerable."

To drill down, Schell offered four common immersion-breakers:

Shallow object interactions. Game objects often have one purpose and one purpose only; they're not versatile. Real-world objects are not so limited. In Schell's game there's a knife, and players expected to be able to use it to unscrew screws -- a task you need to complete. So the developers had to make sure it did.

"As soon as it doesn't work," said Schell, your brain screams "this world is fake, this world is fake, this world is fake."

"Bit by bit, you have to watch how people try and use objects and you have to use that."

Unrealistic audio. "Generally, we're finding you have to spend twice as much time on sound design," said Schell. "If you drop a coin and it bounces off of a carpet, and if it bounces off a cobblestone street and makes the same sound," he said, it's back to "this is fake, this is fake, this is fake."

Proprioceptive disconnect. The body knows what position it's in. If your avatar is in a different position, it's presence-breaking. I Expect You to Die doesn't have an avatar at all: "our brain is willing to tolerate the body not being there; it's better than it being wrong," Schell said.

Interfaces that are just generally unnatural. The game originally had a convoluted rotation motion for unscrewing screws; that did not work. That's because, in real life, it's something we've all done so much it's an "automatic motion" -- we do it without thinking about it.

So the team switched to a scheme where you simply hold the screwdiver up to a screw and it automatically unscrews. "It just works, and our brain doesn't mind it," Schell said. "The reason it works is because, 'Why the hell else would I have it there?'"

Lesson 4: Looking around takes getting used to

"People new to VR don't look around," Schell observed. "We've had a whole life of interacting with digital media where you sit still" and stare forward, he pointed out. At least when building early VR experiences, you have to encourage the player to move around. I Expect You to Die takes place in a car, and people expect things to be in a car's backseat, so they're more prone to look. Early in the game, there's also a laser you have to dodge, so you learn that you can move your head to avoid threats.

And, notably, "it's really fun to look into things," for players, it turns out. "It's really super fun to look into stuff, over stuff, behind stuff." So there's an advantage here, too.

Lesson 5: Different hardware enables totally different experiences

"If you think you are going to make one game and adapt it to all of these [VR] platforms, good luck buddy," Schell said. "Pick one of these platforms and optimize for it." The GearVR is out now; next year, the Oculus Rift, PlayStation VR, and the HTC Vive will all launch. Each will be different.

But what's his favorite interface? "I really believe long-term, systems like the [Oculus] Touch are going to be the primary way people are going to want to interact with VR."

The Oculus Touch

Lesson 6: Iterate ... a lot

Of course, developers know that iteration is the rule. But in VR, said Schell, "you need to iterate even more."

That's because "traditional games are about exploring and environment, and interacting with an environment. VR games are about exploring interactions of objects and manipulating an environment."

"When you manipulate an environment, you mix and match things," Schell said. "What will this rock do against this window? ... In order to figure these things out you need to iterate more."

He closed with this admonition: "This is a very, very special time. If you've come to VR because you want to emulate the games you've been playing for the last 20 years, get the hell out of here."

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like