Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

On Building A Procedural Retro-Themed RPG

A excerpt from Game Art, an upcoming book featuring interviews with a wide range of different game developers and artists, from independent developers to those working at the biggest blockbuster studios.

In the world of video games, "art" doesn't have to mean "high-end graphics." Just like independent film makers who create cult hits and arthouse darlings with limited equipment, independent game developers on limited budgets are producing new classics that don’t conform to AAA expectations. Some of these developers have epic ambition, driving them to create sprawling, massive, and intellectually interesting universes to explore. Hello Games' No Man's Sky is an obvious example, but then there's Alex Norton’s Malevolence: The Sword of Ahkranox. Largely the work of one man, Malevolence is like Wizardry or Might & Magic set in a procedurally generated world that dwarfs the size and scale of any Elder Scrolls game, and it is a true testament to what a single independent developer can achieve.

This interview with Norton is an excerpt from my upcoming book, Game Art (available at No Starch Press' website and on Amazon). Norton is just one of over 20 creative game developers featured in the book, including individuals from indie studios like E-Line Media as well as blockbuster studios like Bioware and Ubisoft. I hope you enjoy the read!

Malevolence: The Sword of Ahkranox is a game that was almost never made. In fact, if creator Alex Norton hadn’t faced personal tragedy, he might never have been inspired to develop it in the first place.

“A few years ago, I fell very ill and was hospitalized,” Norton said. “I had to have some surgery, and the doctor gave me an 87 percent chance of not making it through. As you can imagine, that was pretty terrifying.

“The last thing I remember thinking as I was wheeled into the operating room is that if I didn’t make it, there’d be nothing of me left behind. Weirdly enough, it brought back memories of how I hated when the games that I’d played as a child ended.”

Many parents read stories to their children at bedtime, but Norton’s dad was different; he worked night shifts, so he couldn’t read to his child at night. Instead, during the day and on weekends, Norton and his father bonded while playing classic RPGs, such as Eye of the Beholder and Might & Magic.

“When we came to a crossroads, my father would ask me which way we should go,” Norton said. “It was better than a bedtime story because it was something that we were living and breathing together—a world that we got to be a part of.

“As I got older and we would finish the games, I hated that they would end, because the next one was never quite as good—they started to modernize and lose their luster. So, when I came around after the operation, determined to create something I could leave behind, I thought, ‘Why not make one of those games that was such a part of my childhood?’ But I’d make one that would go on forever.”

A Procedural RPG

With months of time on his hands as he recovered, Norton threw himself into developing his game. For a college project, he had developed an engine to create infinite procedural worlds, but this was before Minecraft and other “never-ending” games were popular. So at first he wasn’t convinced that he could make a successful game.

But as he tinkered with the engine, Norton realized he could indeed use procedural worlds to produce a compelling RPG experience. He took his idea to the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter and discovered there was a lot of interest in the project.

“I brought in a few friends who were good artists, and a composer, and suddenly Malevolence became a big deal,” Norton said. “The scope of the project exploded, and I realized that this could be something really special. Malevolence generated a savage following. They’re a niche group of players, but they’re massively dedicated to it.”

Malevolence’s main demographic is the over-30, lifelong gamer who shares Norton’s nostalgia for classic RPG mechanics. Just like Norton, these players find the idea of having one essentially endless game immensely appealing.

Open-Ended Storytelling

Open-Ended Storytelling

Malevolence has a classic RPG structure that gives you the chance to explore trap-filled dungeons and kill hordes of monsters, gaining experience, new weapons, and plenty of loot in the process. Unlike its peers, however, Malevolence also borrows from games like Minecraft by offering players a procedurally generated world. New environments are randomly generated, and the game world is truly infinite.

But Norton came across a challenge almost immediately. With their entirely randomized worlds, procedurally generated games can’t, by definition, have author-created stories. The game designer can’t predict your experience, so a standard game narrative doesn’t work. Norton had to devise a different way to give the game structure.

“Malevolence does have a narrative, but naturally, it couldn’t have an infinite written narrative. I would have had to hire someone forever to keep creating content!” Norton said. “So I experimented with interlinking the players.”

Malevolence explains its world in an introductory scenario, but it doesn’t have a prewritten story beyond that. The game is set in a dream world created by a sentient magical sword, and you play as the physical embodiment of that sword’s will. In this scenario, every player is effectively the same character (the manifestation of the sword’s will) exploring the same world (the dream of the sword) at the same time.

Players don’t meet each other, but they share a universe, and their actions impact other players’ games. When you enter a dungeon, a notice tells you the name of the first character who entered that dungeon, and if one player’s character dies, other players find that person’s body in their world. Players can also drive their weapons into special stones for other players to pull out, a mechanic that borrows from the Arthurian legend of Excalibur.

These elements allow Malevolence players to write their own legends, and fan events have even become part of the game’s lore.

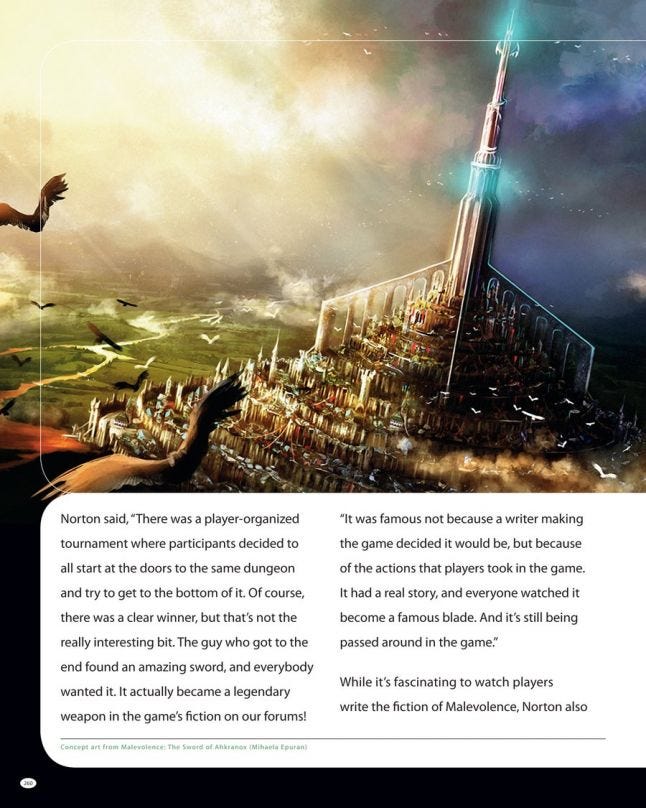

Norton said, “There was a player-organized tournament where participants decided to all start at the doors to the same dungeon and try to get to the bottom of it. Of course, there was a clear winner, but that’s not the really interesting bit. The guy who got to the end found an amazing sword, and everybody wanted it. It actually became a legendary weapon in the game’s fiction on our forums!

“It was famous not because a writer making the game decided it would be, but because of the actions that players took in the game. It had a real story, and everyone watched it become a famous blade. And it’s still being passed around in the game.”

While it’s fascinating to watch players write the fiction of Malevolence, Norton also realized that this community-based storytelling wouldn’t be immediately accessible to new players, especially if they didn’t want to join the forums. So he released an expansion pack with a predefined narrative arc.

“The expansion pack has a story with a proper ending. It gives a purpose to your existence in Malevolence, which the base game doesn’t really have,” he said.

And whether you choose to create your own purpose in Malevolence or let the game provide one for you, your tale only ends when you want it to—just as Norton dreamed.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like