Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

3 Massive Problems Confronting Storytelling in Games

There are 3 massive problems that prevent games from telling great stories: The Problem of Systems, The Problem of Groundhog Day, and The Problem of the Uncanny Valley. I attempt to define and solve them.

The best stories told in video games today are pale shadows of the best stories told in books, movies, and the stage today. Why?

Games contain huge, unavoidable obstacles that prevent traditional storytelling.

Here are the three problems of game stories, in order of severity:

1: The Problem of Systems

Systems make games fun, but other media boring. Players enjoy learning, playing with, and mastering systems.

How games use systems:

Games spend hours chronicling every footstep and reload that a soldier makes during a firefight. No movie would ever do that. Complex combat systems make it fun. It’s fun to manage ammo, weigh the risks of advancement, use cover, then pop out and get those headshots. Failure to use the system well results in a short backpedal and a lesson about how the system works. The interesting part of a war game is the gunfight. "Will a flashbang stun the guys in the bunker long enough for me to fire two rockets at the tank?"

How movies use systems:

But in movies, gunfights are only interesting after we’ve formed an emotional bond with the characters. Fantastic war movies like Apocalypse Now, Black Hawk Down, The Hurt Locker, or Full Metal Jacket spend far less than half their running time on yelling and shooting. The fun comes from characters interacting. "Jeff has been a reliable soldier, but he's going crazy. Will he get everybody killed in the next raid?"

Books are even less action-focused, with For Whom the Bell Tolls, The Killer Angels, and The Red Badge of Courage spending pages and pages on the thoughts and feelings of their characters. "I volunteered for this, but I think I might be a coward. Whoops.'"

The same story, told differently:

A book, a movie, and a video game can all tell the same story. But the fun in a game comes from the opposite place than it does in a book or a movie.

Learning how to fight in a movie is a two minute montage. Learning how to fight in a game is hours and hours. It’s practically the whole experience.

By the same token, character development in a movie is hours of talking. Character development in a game is a two minute cut scene.

Yes, this is an oversimplification. You can combine action with character development, and most stories do. But we can make a clear divide between "Sitting and Talking" and "Running and Shooting," to illustrate the strengths and weaknesses of each medium.

This is a huge problem for storytelling in games. Conventional writing does not work. The itch to get back to the action, to the system, overpowers most of the character development and plot a writer would want to present. When we play a game, we become very goal-oriented, and we want to live in the system. Anything that takes us out of it is an obstacle between us and our goal. Even death is a known, measurable part of the system. Story, on the other hand, usually isn’t.

Cutscenes: worse than death?

Death, in a game, is a temporary setback that keeps us from our goal for a set amount of time. We quickly learn exactly how long it takes to watch the death animation, hit the "reload" button, and get back to the action.

A cutscene, in a game, is a temporary setback that keeps us from our goal for an uncertain amount of time. We don't know how long these characters are going to talk, what they're going to talk about, or if it's going to be interesting. In games, cutscenes can be worse than death.

I enjoy a certain amount of cutscenes, but my personal tolerance hovers around the < 5 minute mark. Games face an uphill battle when forcing the player to stop playing long enough to become emotionally invested.

Games live or die by how great their systems are. Traditional storytelling doesn't work with current systems.

Can it be solved?

Maybe.

The best way to cultivate emotional investment is character development and interaction.

In life, we have many goal-oriented conversations, based on what we know about the other person and how to use words. Conversation is a system.

Theoretically, a system for conversational interaction could be the basis of a game. If players know what they want when they approach an NPC, if their skill at manipulating the conversational system impacts the results, and if the system is fun, then a whole new level of gaming is in reach. Character development and emotional involvement unlocked. Level up. But it's not going to be that easy.

Games have made fantastic strides in a players’ ability to interact with the world, enemies, and their own gear. But systems to explore the emotional core of humans interacting with humans still seems miles away

A gun in a video game is a simple, fun, rewarding tool for interaction. The “press A” prompt to start a conversation is not. A gunfight creates a system based on skill, with learnable punishments and rewards. A branching dialogue tree does not.

Breaking ground and watching your stadium go up in Sim City is fun and rewarding. Collecting enough sun to place your fifth Melon Pult in Plants Vs. Zombies is fun and rewarding. Drifting past the Ferrari on a tight series of turns in Need for Speed is fun and rewarding. Choosing the “polite” or “rude” response is not.

Without a system of interaction that can be learned, manipulated, and mastered, human interaction will continue to be an obstacle.

2: The problem of Groundhog Day

A player will always be able to replay events until he gets what he wants.

In the movie Groundhog Day, Bill Murray’s character is forced, for unexplained reasons, to relive the same day over and over, tens of thousands of times. Every day he tries something new, but every morning he wakes up back in the same bed in the same town on the same day: Groundhog Day. In one sense he's trapped, but he can do anything he wants, all the time.

Video game players can replay any scenario until they get the outcome they want. The designer can't effectively force the player to make a certain decision.

Replayability is a superpower, probably the best superpower. We can be immortal. We can be infallible. We can try infinity times. With each life, we create an alternate universe, and the one we stay in the longest is the one that brings us to victory. The level 8 boss might be as big as a house and have claws for hands, but nothing can stand against an infinite, immortal, infallible gamer.

“I’m a god,” says Bill Murray.

“You’re God.” Says a sarcastic Andie MacDowell.

“I’m a god, I’m not the God. I think.”

“Because you survived a car wreck?”

“I didn’t just survive a wreck. I wasn’t just blown up yesterday. I have been stabbed, shot, poisoned, frozen, hung, electrocuted, and burned. And every morning I wake up without a scratch on me, not a dent in the fender… I am an immortal.”

In games, so are we. And that’s a big storytelling problem.

The same fears and motivations that affect characters in other media, and affect us in real life, don't work on our game avatars. We routinely barge into stranger's houses, attempt 20-foot roof leaps, and charge demon platoons without a second thought. The problem of Groundhog Day ruins tension. It ruins believability. It creates dissonance between the abilities of the gamer and the story told by the developer.

If certain events need to happen in the story a developer wants to tell, the player can’t have any choice at all regarding those events. The player will choose what they want, not what the storyteller wants, and they'll choose based not on normal human wants and needs, but on the wants and needs of an immortal. A developer must choose carefully what freedoms to give the player.

Games create immortal characters with unusual motivations. Traditional storytelling doesn't work with such superhumans.

Can it be solved?

Probably.

Solving the Problem of Systems and the Problem of the Uncanny Valley would go a long way. If the NPC's are allowed to drive the story, and player choice does not affect major plot points, then the designer is free to write anything. Then it remains to align player motivation with the game world.

3: The problem of the uncanny valley

Art and technology have not advanced far enough for designers to be able to create realistic, believable characters in a game.

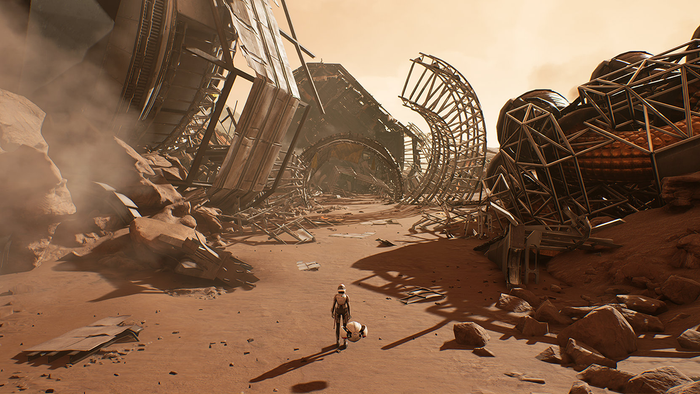

There is one emotional driver that games do better than any other media: immersion. There is no other experience like being in the world of Thief, Myst, Mass Effect, Rage, or WoW. Movies cap out at three hours and books place you inside heads better than inside worlds. Games create environments that captivate you for weeks.

But the illusion falls apart when you approach one of those beautifully rendered, carefully-animated NPCs. The simple scripts that run their brains can not compare with the elaborate scripts that generate the shadows under their noses. Alex Vance may have a great program that dynamically alters her level of eye contact from moment to moment, but if you want to hear what she has to say, you’d better be ready to listen to a canned phrase about her admiration for you. The innards of an NPC now are about the same as they were in 1995, while the outsides have undergone a massive makeover.

We know humans too well. The best NPC human in the world will reveal its inhumanity within 30 seconds of interaction.

The uncanny valley is a huge obstacle to emotional engagement. Every time Alex Vance repeats a phrase, or blocks your passage through a doorway, or stands too long staring at nothing, you are reminded that she is not real. She’s just a program. You don’t need to care about about a string of ones and zeros.

Gamers adapt. We’re able to develop some emotional connections with our uncanny cohorts in games. But non-gamers see the creepiness much more clearly than we do.

I was showing off Mass Effect 2 to my wife, and instead of being impressed by the fantastic voice acting and animation, she said “the dialogue doesn’t sync up very well, does it?” And she was right. For a person used to Pixar’s levels of quality, Mass Effect 2 looks kind of sloppy. We’re coming from a world where pressing X to watch Cloud say “...” is emotionally resonant, and she’s coming from a world where teams of hundreds invest months tweaking Buzz Lightyears’ facial expressions.

Without emotional connection, there's no story.

Can it be solved?

Yes. It’s being solved. Artists avoid the problem by telling stories about animals, bugs, toys, robots, or aliens. Or they stylize the characters in a way that works around the medium’s limitations. Or they use radios and recordings to move the characters off-screen. So while technology catches up, developers are able to use tricks to tell better stories.

In Conclusion:

Games have the potential to tell immersive, compelling, life-changing stories that rival or surpass the stories told by other media. We just need to solve a few problems. I know that many of you are hard at work right now trying to work around or fix these issues. I look forward to seeing your creativity and intelligence on the market soon!

Next: I attempt to solve these problems by imagining Gatsby: The Video Game!

(Thanks Dead End Thrills for the game images!)

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like