7 works of interactive fiction that every developer should study

Gamasutra reached out to several esteemed creators of interactive fiction, and asked them for their recommendations of great works of IF that are instructive exemplars of what the medium is capable of.

“You are standing in an open field west of a white house, with a boarded front door. There is a small mailbox here.”

If you’re of a certain age, you may remember this opening line and have many fond memories of that house, the vast underground cavern beneath it, and the grue waiting for you in the dark. Zork is one of the most memorable examples of a text-based adventure game or interactive fiction, a genre that peaked in the 1980s.

But, it’s enjoying a bit of a resurgence today thanks to studios like Failbetter Games and Inkle. With that in mind, here are seven IF games that can still teach developers of any genre a lesson or two about narrative and design.

1) Spider and Web

Interactive fiction writer Andrew Plotkin’s Spider and Web is a very difficult and brilliant game, but telling you why would spoil it, says Inkle co-founder Jon Ingold. And it’s this sense of mystery that makes it worth studying.

“[It] does do a completely wonderful thing, a thing that was entirely revolutionary at the time,” Ingold says,” and -- while attempted by a few big franchises -- it’s never been bettered."

“[It] does do a completely wonderful thing, a thing that was entirely revolutionary at the time,” Ingold says,” and -- while attempted by a few big franchises -- it’s never been bettered."

"The game presents an impossible challenge, and requires you to think outside of its own frame to solve it, while at the same time never breaking its narrative or its world. It's like what The Stanley Parable does, without any goofiness or any whiff of surreality.”

Takeaway: Don’t be afraid to think outside the box and make your game challenging.

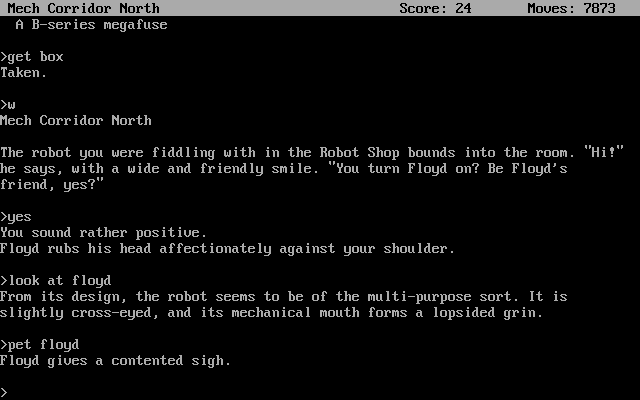

2) Planetfall

The 1983 Infocom game Planetfall is about a lowly ensign who crash lands on a desolate planet. It’s notable for its sense of humor and for Floyd, a robot who helps the stranded adventurer find a way home. Game designer Bob Bates says it’s amazing that creator, Steve Meretzky, was able to craft such a unique character so economically.

“Like the Wicked Witch of the West, who appeared onscreen for only 12 minutes in The Wizard of Oz, Floyd and our emotional reaction to him dominates our memories of Planetfall, despite his limited role in the game,” says Bates.

Takeaway: A memorable character, even a small one, can elevate your narrative.

3) Trinity

Brian Moriarty’s Trinity is considered to be one of the best titles in Infocom’s catalog. Its name refers to the Trinity test, where a nuclear weapon was detonated for the first time. As a London vacationer, the player escapes a pending Soviet attack via a strange door hovering in mid-air. Bates says the game is notable for its unwavering determination to depict the specter of nuclear holocaust that hangs over us to this day.

"Trinity is a wonderful example of what a passionate writer in the grips of a strong idea can create,” he says. “Although the game has some unfair puzzles (you must sometimes die in order to gain needed information and then restore to a previous save), it is still eminently playable. What developers should study is the depth of realism that Brian brought to a work of fantasy, and the cohesion of the philosophical outlook that governs the game from start to finish.”

Takeaway: Any narrative, even a fantastical one, needs to have some realism in order to be believable.

4) Bad Machine

The way you tell a story is just as important as its content, says MIT associate professor and IF author Nick Montfort, and a good example of this is Dan Shiovitz’s Bad Machine. The game’s mechanical protagonist experiences an unexpected failure in its programming that leads to autonomy. This change in its perspective is represented through glitches, database query results and error messages. Learning to decipher this text is part of the game play.

“Dan Schmidt's For a Change is another example, where the text is uncanny and metaphorical, and also full of personification,” says Montfort. “In both cases, the underlying game … would be much less compelling without the unusual style.”

Takeaway: Presentation matters.

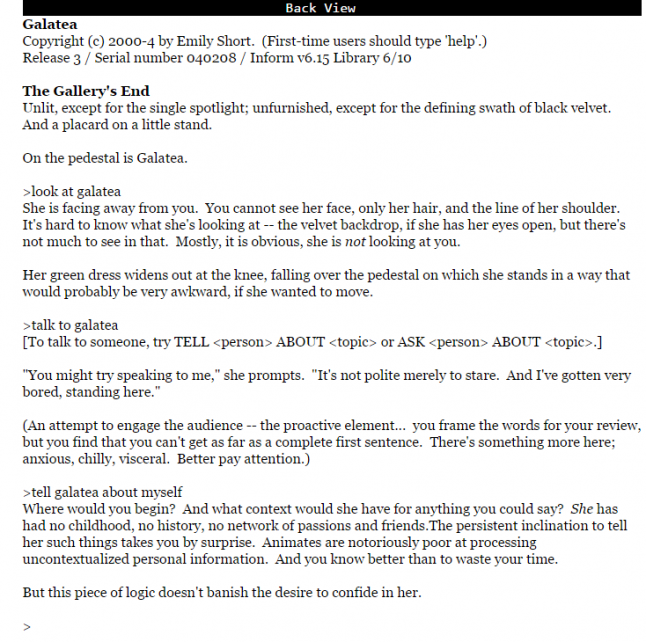

5) Galatea

Emily Short’s Galatea is a take on the ancient Greek myth about a sculpture that comes to life. Unlike most IF games, it takes place in a single room and focuses on the player’s interaction with a single character.

Interactive fiction author Adam Cadre says one of the biggest issues developers face with any narrative is juggling the hundreds of possibilities player decisions create. This leads many devs to use a braiding structure where they spin out a few different paths then tie them all back together before offering the next set of options.

“What Galatea demonstrates is that there is an alternative: you can actually just DO THE WORK,” Cadre says. “It's not impossible to keep track of hundreds of possibilities, or to model complex emotional states, or to allow a player to raise any topic in a conversation and judge how relevant it is to the discussion up to that point. It's just very difficult.”

Takeaway: Sometimes, you just gotta buckle down and create lotsa story branches.

6) A Mind Forever Voyaging

This 1985 Infocom game is perhaps the most determined effort to create a game about politics, says Her Story creator Sam Barlow. As the sentient computer PRISM, the player is tasked with running a simulation called the Plan for Renewed National Purpose. As they attempt to build a better America through deregulation and unilateralism, the country descends into chaos. [NOTE: All three of the Infocom games mentioned in this list can be played on iOS as part of the Lost Treasures of Infocom compilation.]

Steve Meretzky created AMFV during the Reagan administration, and it was critical of the right-wing and populist policies of that time. It specifically focused on the government’s aggressive military stance, the cutting of social welfare benefits, and an emphasis on religious values. Barlow believes the game is particularly relevant given the current political climate. “It's a great example that games can tell and explore narratives that have an overt political message,” he says.

Takeaway: Don’t be afraid to tackle a hard topic in your narrative if it’s something you feel passionately about.

7) The Last Express

Although it’s technically considered an adventure game instead of interactive fiction, Jordan Mechner’s The Last Express deserves a spot on this list, Ingold says. “Is this interactive fiction?” he says. “Yeah, I'd say it is, because the most important thing here is the writing.”

As an American doctor fleeing a murder charge, the player boards the Orient Express and heads toward Constantinople, meeting a colorful cast of 30 characters. The Last Express’ narrative takes place in real time. It’s subtle, witty, and intelligent, but that’s not why you should play it, Ingold says. Instead, you should study the way it uses time as a meaningful variable.

“Because it breathes with life. Because there's a full violin concerto in the middle of it, which is optional. In fact, it's probably inadvisable to listen to it. The Last Express has more to say about character in games, about opportunity cost from minor decisions, than any other game ever made.”

Takeaway: Time-sensitive decision-making can help bring your narrative to life and provide some replay value.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like