.png?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Sam Barlow breaks down the 'pillars of interactivity' behind Immortality

Speaking at GDC 2023, Immortality co-creator Sam Barlow breaks down his storytelling pillars and reveals the acclaimed project owes its success, in part, to the existence of Pokemon Snap.

"Throw away the container." That's the advice Immortality co-creator Sam Barlow has for developers wondering how he pieced together the award-winning cinematic thriller, which asks players to unravel the mystery surrounding actress Marissa Marcel by combing through lost film footage.

Breaking down his approach to design at GDC 2023, Barlow suggests game developers must ditch the rules imposed by 20th century media. He explains the movies and television shows that we grew up with were constructed with certain parameters in mind, such as facilitating ad breaks or the need to physically ship movies to theaters in canisters (the container, in this particular metaphor).The advent of interactive digital media, however, means we no longer need to play by those rules, but ditching conventions that have been reinforced over decades can often feel uncomfortable.

Barlow suggests that, so far, the majority of disruptive media–think Netflix series that can be binged in their entirety on day one–has merely tweaked the container. "They're still writing this piece of television using the same structures," he explains. "So the real opportunity that we have from games is to throw these containers away.

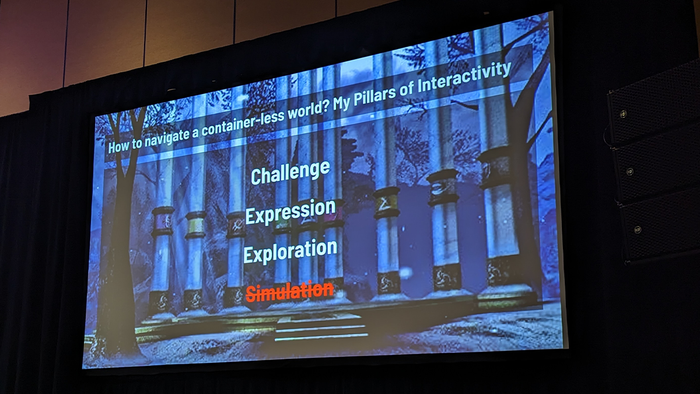

"What happens then? What do you do in the absence of the container? For me, if you look at the core pillars of what video games do best, and can do best, these are the means by which we can navigate this much more open, interesting space for storytelling."

Barlow proposes developers use four core pillars–challenge, expression, exploration, and simulation–to explore the nebulous narrative aether that now surrounds them.

Where 'challenge' is concerned, Barlow notes that when you put any obstacle in front of players–be it a riddle or question–as human beings, they'll be naturally inclined to want to overcome that hurdle. That makes 'challenge' the driving force when you give players agency control in a piece of storytelling.

'Expression,' he says, is rooted in creating mechanics that give players a richness and fluidity to express themselves in a possibility space, suggesting developers will know they've succeeded when players start interpreting those mechanics in dramatically different ways.

Then there's 'exploration,' which according to Barlow is a "fundamental feature" in a lot of video games, because as a "hunter gatherer species" we're all driven by a sense of curiosity and discovery. "What I've been trying to do it take a lot of those verbs around exploration and apply them directly to the story itself. That's been a fascinating journey," he adds.

The fourth pillar is 'simulation,' and Barlow claims this is the one developers sometimes take for granted. "It's very interesting as a human to interact with a simulation and try and rock the rules of the simulation. What I've found over the years working on games is that, as a storyteller, I would lean on the simulation as a prop. But then I started to question how useful it was for my storytelling, so with Her Story in 2015 I explicitly gave myself the challenge of making a game with no simulation–so no state changes, and no tracking of structure."

Using those pillars, Barlow has created three video games so far: Her Story, Telling Lies, and Immortality. Explaining how each of those projects attempts to throw away the container, he says that Her Story ultimately sought to deconstruct the detective story, Telling Lies was designed to be an "anti-movie," and Immortality took that idea further by deconstructing movies and the movie making process itself.

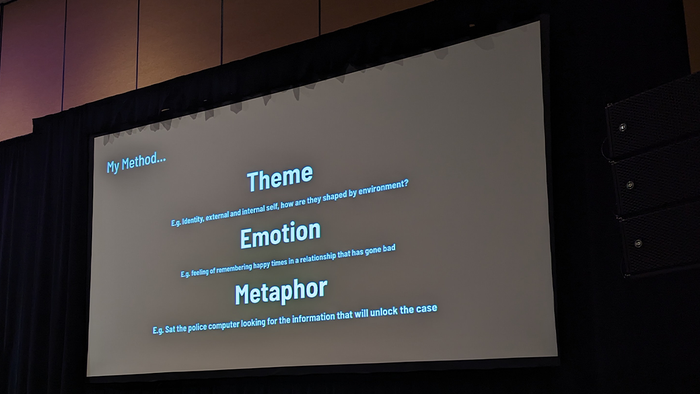

Barlow adds that all of his projects must also pass a "sanity check" by delivering on three separate fronts: theme, emotion, and metaphor. "The logic is, if I have all three of these in place, this is going to be a good game," he notes.

"The 'theme' is: what is the question that we're exploring? It might be a question I don't have an answer to. In fact, those are the best types. So for example, with Her Story, the theme there was 'identity.' Our external and internal identities and the extent to which they're shaped by the environment."

Then there's the emotion, which Barlow says requires him to communicate a very specific feeling that he's experienced without making it sound trite. In Telling Lies, for example, the 'emotion' was centered around the question: how does it feel to have been in a relationship that's failed, but still hold in your head the happy memories of when that memory was working?

As for the 'metaphor,' Barlow admits he might be stretching the meaning of the word, but explains that this essentially becomes the mechanic that describes the game, becoming a really useful communication tool for players.

"So, during this process on Immortality, our theme was 'why do human beings tell stories?' We thought if we're going to do something about cinemas, and looking back at the 20th century, it would be a great opportunity to ask these very deep questions. [...] The 'emotion' was this idea of struggling with the impossibility of creating a perfect story, and it digs into this idea of, if storytelling is something we're compelled to do, the most interesting way to explore that concept would be via an instance of failure."

At this point, Barlow explains he once spent three years working on a Legacy of Cain game that was ultimately cancelled, describing that project as "probably the most challenging thing I worked on and the biggest failure of my career." Afterwards, he began contemplating why he pushed so hard on that project at the expense of his family and the rest of his life. Why, he asks, did it matter so much to him? By grappling with those emotions, Barlow unearthed Immortality's hook.

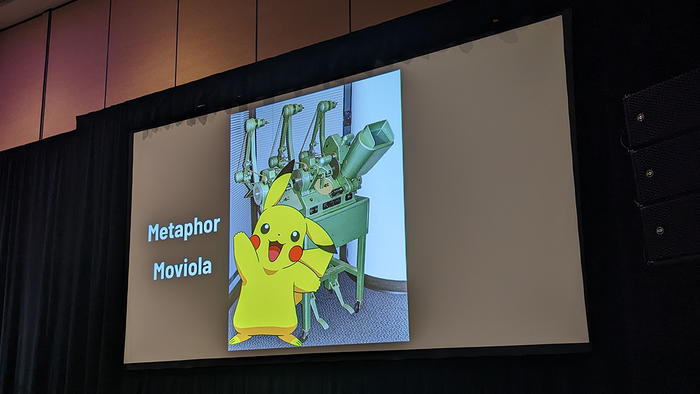

In searching for Immortality's metaphor Barlow landed on the Moviola–which is the name of the device in that lets players explore the game's fictional film reels–and believe it or not, an image of Pikachu. "The very first design doc for the project was this picture of Pikachu with a Moviola. It's a slightly mixed metaphor, but we can expand it and say it's the Moviola in the editing suite," he says.

"The metaphor became 'imagine you're in an editing room and you have all this footage.' It's that process of making a movie when the editor sits down to do the assembly cut, and there's just this vast amount of footage. Then they start organizing it and obsessing over it and going frame by frame and really immersing themselves in the beauty of the film.

"That was our guiding principle and it meant the mechanics would be grounded in wanting to explore the tactile nature of film as a medium versus the digital stuff we're familiar with. But even at this point, the presence of Pikachu shows we were aware that we were also just making Pokemon Snap, essentially. That was another way I justified the project. I'd be doing some weird stuff, and we'd have these ideas, but I also played Pokemon Snap and that was fun. And people like to Pokemon Snap, so this is going to work."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author

You May Also Like