Designing Highfleet, a strategy game with heavy machinery and twirling knobs

Konstantin Koshutin, creator of Highfleet discusses some of the design decisions that went into this new take on the simulation strategy genre.

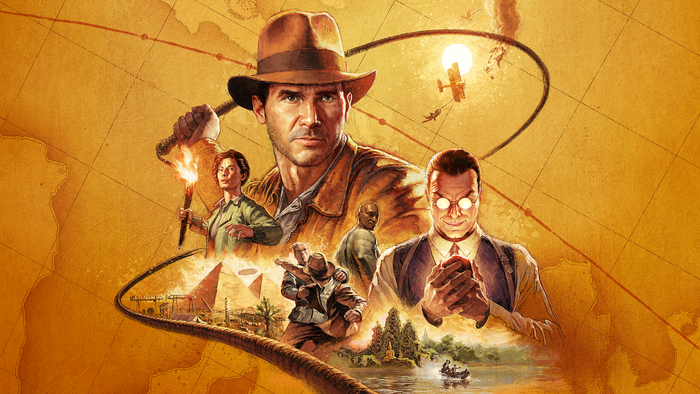

Konstantin Koshutin’s Highfleet (published under the revived MicroProse brand) is a grungy, diesel-fueled fever dream of a strategy game that makes the most out of a diegetic interface to deliver the fantasy of controlling a mechanized airship army waging war in a science-fiction remix of the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.

Core combat of Highfleet is a relatively simple (but deceptively complex) 2-D side-scrolling air combat affair. Players choose an array of airships in their fleet to deploy against their enemies, then try to win by working against the deliberately clunky movement and slow-moving projectiles.

In between missions, players manage the repair and efficiency of their ships in a maintenance mode that evokes the MechWarrior’s Mech Management system, with a number of other systems coming in to create this crunchy interactive strategy game that trades fluidity for frustration in order to build the fun.

It’s a design philosophy that embraces the inelegance of real-world machinery to add tension to a sci-fi setting. We wanted to know more about Koshutin’s process for creating Highfleet’s systems, so we pinged him for a quick chat about the making of this neat game.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity

Hey Konstantin, could you introduce yourself and explain the original idea for Highfleet?

My name is Konstantin Koshutin, I am an indie developer from Russia. And for many years now, together with my friend, we have been working on Highfleet.

I've always been a bit of a military geek, and few things in the world give me more pleasure than grabbing a copy of Janes’ Handbooks (a series of military texts in publication since 1898) and leafing through it in an armchair with a cup of tea, covered with a cozy blanket. In addition, since childhood I have been reading science fiction. So it came naturally to me to combine military hardcore with good sci-fi.

In my time with Highfleet I was struck by how “clunky” everything felt. Ships responded to my inputs but also felt dragged down by their weight or previous momentum. Was it difficult to create this feeling without making the ships feel unresponsive or difficult to maneuver?

Physics is what makes our world so interesting. Physics in soccer, flight simulator, or sword fighting. The game that inspired me to become an indie developer is Gish, one of the pioneers of game physics. It was criticized by many for its awkward handling, but it was the moment of mass that you gradually learn to use that made it a great game!

This is something in the very structure of our brain, we need to get used to it a little, but then you feel the game as an extension of yourself. I learned this lesson and made Hammerfight, which was also called inconvenient to control, but I'm still very happy with the result :)

Something similar happened in Highfleet. For example, many people ask to add a firing aim lead hint as seen in space sims. I tried this several times and the result was disappointing every time. Having received a hint, you stop feeling the physical world, its speed, and inertia. You begin to influence the world not directly, but through an artificial substrate and all the magic disappears.

The game’s diegetic user interface is incredible. All of the knob-dialing and button-pushing feels like a great way to interact with this world. Could you describe your process for creating “menus” that felt like physical systems to interact with?

Well, they have never been perceived as a menu. Rather, it is a small museum where you are allowed to touch and twist everything.

Analogue devices have their own soul, their own aesthetics. The digital interface is certainly more convenient, but it is the analogue interface that gives this feeling of immersiveness. Again, I was born in the analogue world, perhaps my children will be closer to digital.

Building on that question, when players are first presented with the controls for Highfleet, it’s a very dense visual of real-looking machines. What did you learn about teaching players how to interact with this system, and making sure they could understand the game’s more complicated mechanics?

We immediately realized that we would have problems explaining the rules of the game to the players. Veterans of simulation and military strategy games like Harpoon would get up to speed faster, but for the average gamer, there are too many unknown mechanics in the game.

For example, almost all players tried to complete their ships with new parts during the campaign, as is customary in other games. But in the world of Highfleet, it would be very strange if, during a military operation, the admiral turned his corvettes into cruisers.

We assumed that the player would build ships between missions, and during the campaign itself would focus on repairs and minor upgrades. But how can we explain this and thousands of other similar things? Almost no one reads the manual anymore.

We made, as it turned out, a large and rather complex tutorial system. Into the Breach’s tutorial system, where new functions are explained to the player only when they encounter them, helped us manage that complexity

Still, our tutorial turned out to be too short. Now I understand that it was necessary to increase the prologue’s length at least twice-over, gradually introducing the player into the main campaign.

In general, if you are making a game that is not the simplest, interesting training is one of your main problems to solve.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

There’s a lot of depth outside the combat, especially when players start looking at parts for ships, or buying new ships. How do you help players learn what each part does, or each ship is capable of, while keeping it true to the game’s core aesthetic?

On the parts - we don’t. Parts do not play such a big role for the new player. But the types of ships you mentioned are important. Not all players are ready to read what is written in the description of the ship. People just took expensive AWACS (ships equipped with Airborne Warning and Control Systems) ships and sent them into battle, swearing because of poor performance and excessive complexity.

In the game, we simply advised players to take red ships first and forget about all the others. The time will come and players will understand why the rest of the colors are needed.

This game feels partly inspired by the Soviet-Afghan war that started in 1979. (Or more accurately, if Tsarist Russia had been around to participate in that conflict). What inspired you when creating the game’s central conflict, and creating a setting/story that lives in a fictionalized world but has realistic-feeling touches?

That’s right. The USSR went to Afghanistan at the peak of its military power, confident in its strength. And it was as if it had arrived on another planet. Afghanistan, which seemed weak, changed the Soviet military machine to suit itself.

The East has always attracted me. Once in a foreign and ancient culture, you begin to look at the world with someone else's eyes and find unexpected answers. A similar thing happens to Europeans in the stunning film Lawrence of Arabia and the magnificent book Dune. I just happened to be among the strange Europeans in love with the ancient silence of the desert.

About the Author

You May Also Like