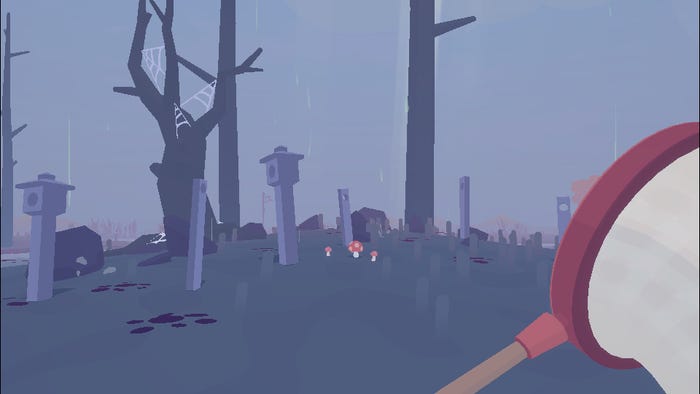

Paradise Marsh asks the player to lose themself in a peaceful marsh, catching insects and critters to restore the stars to the sky.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry.

Paradise Marsh asks the player to lose themself in a peaceful marsh, catching insects and critters to restore the stars to the sky.

Etienne Trudeau, the game's designer, and Rich Vreeland (Disasterpeace), sound designer and musician, spoke to Game Developer about their Excellence in Audio-nominated work, telling us about the game's origin as a fake Famicom game, how they created a harmony between the insect sounds and the world itself, and how to make a beetle sound like Johnny Bravo.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Paradise Marsh?

Trudeau: My name's Etienne Trudeau—but I'm known online as LazyEti—and I designed, coded, and created the art for Paradise Marsh. I worked closely with Raphael Dely who wrote most of the dialogues and poems while Rich Vreeland (Aka Disasterpeace) did the sound design and music.

What's your background in making games?

Trudeau: Over recent years, I worked in the game industry as a 3D and technical artist. In the past, I participated in many game jams and projects, but Paradise Marsh is the first game I completely finished and released commercially!

How did you come up with the concept for Paradise Marsh?

Trudeau: Paradise Marsh's first prototype was originally created during "game by its cover" game jam. The concept is based on a fake Famicom cartridge that reads as follows:

"Nothing is more beautiful than a peaceful wetland. Paradise Marsh is about exploring a perfect, endless marsh. Catch tadpoles, document different wildflowers, and sit on a nice soggy log for as long as you'd like. Now includes a couch co-op mode!"

From there, I just implemented the concept of an intimate relationship to the sky and a few of my own ideas to the mix and it became the game we have today.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Trudeau: 3D models, textures and sounds are carefully put together inside Unity3D and then the magic happens thanks to our homemade tools that procedurally generate the complex world and sounds you experience in the game.

What drew you to create a game about collecting bugs and animals in a marsh?

Trudeau: This aspect of the game is inspired by my childhood when I was living in the countryside and spending all my summers catching insects and frogs by the lake. I wanted to invite players to discover the world through the lens of curiosity and "childish" (meant in the most positive way) naivety.

What thoughts went into the book you fill out about the animals you find? How do you feel this enhanced the experience?

Trudeau: I just wanted to design a UI that felt tangible and physical while keeping track of your progress and giving you a little bit more info about the critters you catch. So, a journal full of little drawings and notes made perfect sense to me. It’s definitely been inspired by the one from Night in the Woods and the Critterpedia from Animal Crossing.

Each animal has specific conditions and biomes under which it may be found (some more specific than others). What ideas went into creating depth of exploration through the various places players can explore and animal behaviors?

Trudeau: When the game was first prototyped, it was clear that critters needed more complex artificial intelligence. That's when I decided to go ahead and make the behavior of all twelve critters as unique as possible. Some of them spawn at night time and others during the day with unique movement patterns. However, they’re all spread carefully across multiple biomes as a way to make the world feel alive and create a balance between bug hunting vs discovering world interactions.

The game ties each creature to constellations, distinct personalities, and writings. Why give each animal a connection to the sky and to deep thoughts? What did you want the player to feel through connecting these elements?

Trudeau: The initial idea to link the critters to constellations was inspired by astrology and Greek mythology. I wanted twelve omniscient "divine" characters with unique personalities who could look over the marsh while still being kind of powerless in the physical world. The intention behind this design was to provide the player with the important goal to save all constellations and justify having to catch multiple critters to do so. I wanted people to feel a sense of progress and usefulness while restoring stars in the empty night sky.

You can make the parallel to some South American cultures in which stars are believed to be the souls of the dead from which would emanate insects that would come to visit the earth. In the end, I think the contrast between the magical-ness of the sky and the more tangible aspect of marsh is what makes the identity of the game so strong!

The audio effects for the various animals and bugs make them sound cute and realistic. What work went into getting the animal sounds just right?

Vreeland: For some of the animals, I tried to mimic their real life sounds. For others, I had to find other influences or come up with something symbolic that would really put their personality first. The spider, for instance, I imagined to be somewhere between Boo from Super Mario 64 and the spiders from Peter Jackson's Tolkien films.

Eti (Trudeau) asked if we could model the beetle's voiceover after Johnny Bravo, so it has a deep, arrogant bug voice. The animal sounds can also be a bit different, stylistically, whether its dialogue or calls out in the world. This has a lot to do with the choice to make the creature calls musical. They always select a harmonious pitch, allowing them [to] weave seamlessly into the musical soundscape of the game.

What thoughts went into the audio design for the world itself? For weaving a mood in this marsh of fallen stars?

Vreeland: For mood, we sought to create all of the sounds using synthesized sources as much as possible and to create a stable foundation from which to have fun things pop out at you (like musical critters and the different sorts of interactions). The music is generally meant to be introspective while also helping you find creatures. The ambient audio is highly dynamic, reacting to the environment around you and what you do, whether it be brushing through cattails or trees, thunder coming from a particular spot with accurate timing and direction, or the pitter patter of rain being different on the surface of water or land.

Eti gave lots of really solid direction about how he wanted things to feel, and I generally ran with those ideas. We wanted the marsh to feel very dynamic and grounded while making the sky feel ethereal and magical. When designing the audio for the star system, I was inspired by The Witness' environmental puzzles, which really make you feel like a wizard as you drag lines across large swaths of the environment.

We wanted the monolith to feel ominous, but also uncanny, so it operates in a different way than the rest of your surroundings. As you approach it and look at it from certain angles, the rest of the audio drops out, or the sound of the monolith modulates completely. Sometimes the hardest part is getting these sorts of choices to really stand out in an effective way. The sanity test for any clever implementation is to test it against a simple one-time sound, or a simple piece of looping audio, and see if it makes that much of a difference in people's experiences.

What challenges come from trying to capture a 'natural' feeling in music? What ideas go into creating a song that sounds like the open wilderness?

Vreeland: I think "open" is a key concept in trying to devise a system that feels natural and works in most contexts. I took cues from my work with Troupe Gammage on Solar Ash, which in turn was heavily influenced by the music system from Breath of the Wild. The music phrases are generally slow and have plenty of silence between them so that the game breathes and the player is never overly inundated.

The system is also driven to a large degree by the location of creatures. Music will emanate from nearby creatures, and if there are none nearby, you will get music that is lonelier and more ambient.

In nature, there is all sorts of genetic mutation and differentiation, and the music system plays with a similar idea by creating infinite variations upon itself. The music contains a few different "moods," each with 20 phrases where each phrase contains three solo performances that are meant to be played alongside each other.

However, these three layers are modulated in all sorts of ways, whether it's volume, panning, pitch, effects, delaying the timing, reversing, and so forth. Some of that can be attributed to laziness, as at times I had more fun building out variation in code than in just creating more assets. But ultimately, the focus on diegetic audio (ie. sound in the physical world), whether it be environmental cues or music, and having systems drive a lot of the audio, helped to keep things feeling intelligent and natural.

There is a sense of connectedness between the player and Paradise Marsh that comes from the sounds of the world. What ideas go into composing and effect choice when trying to make the player feel a kind of attunement with a natural world?

Vreeland: A lot of attention was given to trying to make the sounds and (by extension, the world) feel organic, and to help the player be attuned with what is happening around them. I tried to incorporate lots of subtleties in hopes that they would add up. Some of the minor details include the way the wind changes as you walk around a tree, or the way it blows past your ears when you're moving extra fast.

The sound of creatures is a bit different when it's reverberating from further away, and each creature, even within the same species, has a slightly different sonic behavior. There are lots of little things like this in the game, and in a vacuum they may not be noticeable or amount to much, but the hope is that they all accumulate to encourage a heightened sense of awareness and immersiveness.

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2023About the Author(s)

You May Also Like