Jason Hickey, lead environment artist on Insomniac Games' upcoming Spider-Man offers practical tips about what it takes to be a great environment artist -- and no, it's not all about making pretty things.

Jason Hickey is lead environment artist at Insomniac Games.

Do you know what makes a great environment artist? It's probably not what you think. Environment art is not about making pretty things.

Well not just about making pretty things. The greatest artists I have worked with have been amazing visual designers but also excellent decision makers. That's the trick, you've got to be able make great decisions.

Effective decision making as an environment artist means understanding the technical process, the intent of the gameplay and story, and the aesthetics of the space being created.

Imagine this horrible scenario:

The world exclusive demo of your game is next week and your level is on the big stage. It's a dream come true. Everyone will see it and it looks beautiful. Unfortunately it just won't run. The GPU spikes at every review. It crawls at 12fps and all the LODs are showing only their lowest mips. It's all gone horribly wrong! The worst part is that even when it does hit 30fps, nobody enjoys playing it. It's a disaster.

But it's pretty, so at least you have done your bit, right?

Wrong.

"Environment art is not about making pretty things. It is about making fun games that people can play — just like every other part of game development. You have to make it fun and beautiful."

Environment art, I'll say it one more time, is not about making pretty things. It is about making fun games that people can play — just like every other part of game development. The only possible difference is that you have to make it fun and beautiful.

You have a lot of responsibility. You will need to work across disciplines and be able to make important, informed decisions daily. I am not talking about what color the table cloth should be but how you are going to help make the game more fun and make it run smoothly.

The biggest blocker in new artists is the confidence to make these decisions (which stems from not knowing how to prepare for the unknown — I will address that too). Making the right decision is easy. You just need to understand the intent of your level, prepare for the unknown, make your decision based off all this and double check you achieve the intent.

Hickey is lead environment artist at Insomniac on Marvel's Spider-Man

Hickey is lead environment artist at Insomniac on Marvel's Spider-Man

Step 1: Understanding the Intent

With good directors, this can be super easy. I am working as lead environment artist on the Spider-Man game at Insomniac and they have made the direction of the game very clear. Without spoiling anything – the game should make you feel like... Spider-Man! I am a fan so this was an easy thing for me to wrap my head around.

Sometimes things can be a lot less clear. If you find yourself in a situation where you do not know what your game is and why you are making it, I encourage you to sit down with your game director or creative director or whoever has the vision and really understand it. Then take the notes you have made and construct three pillars for yourself – if they do not already exist.

A pillar is essentially a word or phrase that you can easily remember and sums up the player experience. It should be something very clear (but can have secondary meaning and subtleties too) that you can apply to each discipline in a meaningful way. I have included a sidebar of pillars that I have seen during my career before I started my latest role at Insomniac Games.

GOOD PILLARS | COMMON PILLARS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Intimate Brutality (Conjures up emotions and can affect animation, gameplay and even materials) |

| ||

Altered History (Especially useful for env and character but it's implied realism could affect animation too) | HYPERREAL (not bad in some respects but too open to interpretation on its own) | ||

Isolation (A lot of meaning for environments, audio, animation, character design - good pillar) | Idealized Reality (great words but again very much open to interpretation - whose ideal?) | ||

Relatable (This seems a bit fluffy but applied to a sci-fi game this is a great pillar for environment, audio, character's, dialogue) | AAA_insert_department_here (so many types of AAA games, this is not helpful) |

After this I would do the same thing for the level you are about to work on. Figure it out with your designer. Is it to show off stealth? Introduce you to a new move or character? Maybe it's a hub space? Maybe it's supposed to scare the player or make them feel almighty? Understand the final vision of the fun of the space. It may not be fun for a while, especially if it's the start of development, but try to visualize the potential fun of what it will be by release.

SAMPLE CHECKLIST OF DESIGN INTENT | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

Mood | Humor, Stealthy, Action! |

Mechanics | Basic Combat, Traversal, Puzzles |

Story | Sad, New Character, Epilogue |

Stage of the Game (what comes before & after) | Tutorial, Low Intensity, Last Boss |

Don't forget to understand your company's goals and those of your publisher. For example, taking some invented goals, your game may be being made to tell a compelling story or just focus on core mechanics. It could be all about helping sell hardware, inspiring other developers to make games or showing off technical power of an engine/console.

SOME IMAGINED BUT POSSIBLE COMPANY/PUBLISHER PRIORITIES |

|---|

Another Number 1 hit (raw games sales and reputation) |

Innovate (show they can outdo their competitors) |

Broader fan base (reach more people, change more lives, sell more units) |

Sell Engine (show off all the cool new features!) |

Sell Hardware (complicated! depends on lots of business factors like timing and other titles in production) |

Hickey was lead environment artist on SIEE's Playstation VR Worlds (2016)

Step 2: Preparing for the Unknown

Work with other people to make decisions. You get perspective; you see things from another point of view. Especially work closely with your level designer and someone technical who can help you understand the engine and hardware constraints — usually a friendly coder.

"Imagine you have $100 to spend on the scene. You must decide to split it up between departments based on the scene's priorities. Where will you spend your cash?"

Talk to your lead or art director and ask what the visual showcase is here. By showcase I mean the department who is going to have the biggest budget to work with. Is it a VFX heavy scene? Perhaps you will be seeing a lot of overdraw and transparency? Or a crowd scene? Maybe nothing but environment? This will help you Greymesh (accurately modeled and modularized version of the level without textures) the scene as well as possible while considering other departments' budgets.

There is a handy way of thinking about how you approach a complex scene in games that I learned at a previous studio. It has various names (like the $100 exercise) and it helps people to understand budgets. Especially non-technical decision makers. You have 100 points (or dollars) to spend on the scene: You must decide to split it up between departments based on the scene's priorities — where will you spend your cash?

Here's some arbitrary examples. These are not thought through, just something to make you think.

DEPARTMENT | $100 EXERCISE: | $100 EXERCISE: |

|---|---|---|

Animation/Cinematics | $15 | $5 |

Characters | $40 | $10 |

Env/VFX - Destruction | $10 | 0 |

Environment | $10 | $70 |

VFX (overdraw) | $20 | $10 |

UI | $5 | $5 |

The decisions here should be 100 percent supported by both design and code. Your decision may not be popular when you suggest it first but if you are following the true intent of the level and making sure it is technically achievable then you should win that support. Get good at seeing the problem that you are trying to fix from the four following different views: The Designer, The Coder, The Artist and most importantly: The Player.

I am going to mention this one more time because it is important: Talk to a coder before signing off on a design blockout. There are so many ways to build a level well while achieving the intention so do not be lazy and then cause headaches for everyone later. Remember to ask about: GPU, CPU, memory and whatever else you need to worry about.

Lastly do not forget about reality or "The Schedule". Do not turn ideas down because you thought you did not have enough time or take on more than you can achieve and miss your target. Create an Asset Bible during Greymesh. By having a list of all the work involved in completing your level and accurate estimates in place, you will know what can or cannot be achieved early. This is the greatest tool to help make realistic decisions.

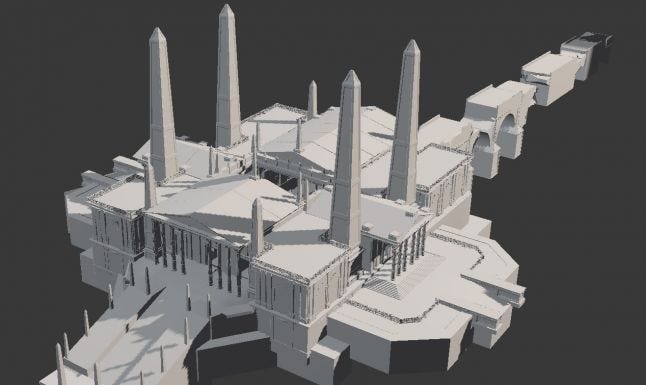

Hickey was lead artist on Ryse: Son of Rome (2013)

Hickey was lead artist on Ryse: Son of Rome (2013)

Step 3: Making the Decision and Evaluating against the Intent

Let us take an example hypothetical level based off the pillars – An Empty Palace to explore.

The Pillars are: Altered History, Relatable and Isolation. So, it is a version of our world, probably set in the past where there are not many people. Importantly it is not fantasy and we should be able to relate. Let us say it is set in the 1980s (Relatable and History), loads of people are dead from a cold war nuclear attack (Isolation and Altered History) and this level is in Buckingham Palace (somewhat Relatable).

Understanding the Intent

What do you think would make this fun? Stop a second and think about that and the pillars. Right, have you got something? I will go ahead with my example but try to think of how this would all work with yours. As it is essentially a 28 Days Later minus-the-zombies scenario, I think the fun would be about hiding out in a forbidden place. There would be a lot of exploration, probably traversal and maybe even some stealth or platforming.

Let us say our fictional studio's goal is to "Sell the Engine." What cool tech can you show off here? Maybe a voxel based lighting solution, world-building tools, vegetation or alembic system – perhaps it's a robust cinematic editor?

"If you can communicate well with your team and be as prepared as possible you have nothing to fear about making your own decisions and suggestions."

Prepare for the Unknown

The designer tells you that our fictional level should have a forbidden and abandoned mood. The gameplay will involve lots of exploration, some stealth and introduce some new traversal mechanics. This part of the story comes after a sad moment but leads the player to find some hope. It is a low intensity section of the game giving room for storytelling and contemplation. It is also an environment-heavy visual showcase so be prepared to try to push the limits of what the engine can do (without being sloppy).

Considering the level from the four different viewpoints:

The Designer will be happier if we give players lots of areas to explore (backrooms and side passages). Also include some destruction to add drama and create new platforming opportunities.

The Coder would like a level constructed with dog legs/streaming gates, modularization, early prototypes and helpful lighting setups (perhaps letting sunlight from outside is cheaper?).

The Artist (you) will want it to be pretty.

The Player is probably going to want to sit on a throne and see some royal artifacts. Make sure you are fulfilling some player fantasy here. Make it memorable besides just a cool location –What about building Princess Diana's rooms (it is the 80s after all)?

The schedule: You have three months to complete the level starting from nothing. You are on your own. Eek. What are you going to optimize so you can deliver it?

Making and Evaluating your Decision

Your designer proposes an opening for the level: The player drives a truck through a wall and knocks over a large water container. This floods the first room. How might we respond to this, knowing the agreed intent of the level?

I have tried to show some thinking process in how this might evolve from a "yeah sure" response. At first you question the idea, "is it what was originally intended?", and finally propose something that you think will work. Something that includes elements of the designer's new idea but still hit the original intent.

Go for it, it sounds epic, maybe we should change part of the level to be VFX heavy instead of environment art only?

This sounds like it might show off some cool water tech. That's a company goal ticked.

If we ram through the front gates of the palace, that would be much more relatable than just starting inside.

Maybe we can show off some of the Altered History here too (bombed out palace and London in background).

However the real design intent for this was to have an empty palace to explore. It's more about isolation than anything.

Over the whole game maybe this was decided to be slower pace because of crazy action everywhere else?

What about entering on foot, seeing the palace grounds and having water flooding a room that you must walk through? Perhaps it's stagnant (Isolation and History)? Maybe we get destruction caused by player walking through the level instead?

If you can communicate well with your team and be as prepared as possible you have nothing to fear about making your own decisions and suggestions. I'd recommend the first few times to check with your lead to confirm. Once you have the same vision then you can start to become more autonomous. And best of all, after Greymesh, once all the big problems are solved we can get down to our guilty pleasure: spending all our time making pretty things!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like