The Entertainment Software Ratings Board is a key part of the game industry, but do you know exactly how ESRB employees rate video games? Gamasutra spoke to Patricia Vance, president of the ESRB, to analyze the process and a day in the life of a game rater.

The Entertainment Software Rating Board (ESRB) employs a team of full-time game raters to assign ratings to over 1000 video games each year. To protect the independence of the raters and the integrity of the rating process, the identities of the individuals who review the games and propose the ratings are kept secret.

This carefully selected group faces an extraordinary task: consistently hold each game to the guidelines of the ESRB system, and to confront new issues as they arise while also staying true to precedent. With a constantly-changing industry and the ebb and flow of the seasons, the group of six can assign ratings to 150 games a month during the rush up to the holiday season. As a key part of the ESRB rating process, no fewer than three raters review a DVD or videotape of the pertinent content in a game. This footage is prepared by the publisher.

Without a reputable ratings process, it's often said, the video game industry might well be prone to government intervention and regulation. Despite the video game industry's existing self-regulation of content, states continue to put forward bills or pass statutes which place limits on the sale and content of videogames. Thus far, almost all such bills have either failed to become law, or been struck down by the courts.

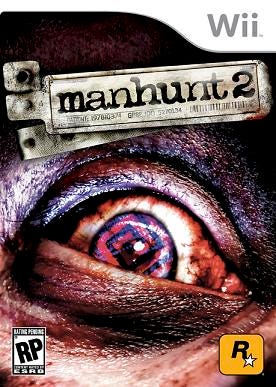

And even as the ESRB protects the industry from outside regulation, the very industry it was set up to aid can occasionally chafe under the rules. Look no further than the Adults Only (AO) rating that Rockstar's Manhunt 2 received earlier this year. The ESRB stood by its rating and its process, and ultimately the game received a rating of Mature (M) after changes were made to its content.

Given the importance of this process and the secrecy surrounding the ESRB raters, we felt it would be important to engage the ESRB and find out as much as we could about the raters and just how they make their determinations.

Given the importance of this process and the secrecy surrounding the ESRB raters, we felt it would be important to engage the ESRB and find out as much as we could about the raters and just how they make their determinations.

Since we couldn't put our questions directly to the raters, the president of the ESRB, Patricia E. Vance, agreed to field our questions instead.

Tell us a bit about the people who rate games. How many raters does the ESRB employ? How are they selected?

Patricia Vance: The ESRB has a staff of six full-time raters, and they're hired through a fairly straightforward interview process.

What kinds of things are you looking for in the raters? Do they have to be gamers?

PV: We prefer raters who've had experience with children, whether through their profession or by being parents or caregivers themselves. We also want people who are articulate and thoughtful, able to express and defend their opinions about content, as well as people who are familiar with video games. They don't have to be hardcore fans, but they should have experience playing games, especially since part of their job is to test final product after its release to confirm that the original submission materials prepared by the publisher reflected the final product.

How diverse is your pool of raters?

PV: Our group of raters includes a mix of male and female, parents and non-parents, hardcore gamers and more casual gamers, younger and older. We recruit from the New York metropolitan area, which has one of the most culturally and socially diverse populations in the country.

How long have your raters been working at rating games?

PV: We just transitioned earlier this year from part-time to full-time raters, so our current group of raters has been rating games for less than a year, with the exception of one rater who had previous experience as a part-time rater. However, given that they're doing it full-time, they're gaining more experience and building expertise far more quickly than our part-time raters were able to.

How many games does each rater examine per month? Do raters work on more than one game at a time?

PV: The number of games a rater will review on a given day or during a given week depends more on the time of year than anything else. Our busiest time is during the summer as companies submit the games they're readying for release in the run-up to the busy holiday season. During those peak times the raters can review around 150 games per month.

What's the most time consuming step of that process? Where does a rater spend most of his or her time?

PV: It's really tough to generalize about these kinds of things because the type of product that we rate is so varied. It really comes down to the individual submission. Some games might have a long submission video, but the rating will be fairly apparent and not much discussion will be required. For others it's the opposite, where the raters' dialogue is the more time-consuming part of the process. Our focus is on thoroughness and thoughtfulness, not how long it takes to achieve those things.

How are games assigned to raters? Can a rater request a specific game, or is it done randomly?

PV: Raters cannot request specific games to rate. We'll have a docket of games that are set to be rated on a given day, and the raters' time is scheduled accordingly. There's effort made to have each panel be as heterogeneous as possible, such as trying to have both male and female represented, but on the whole it's a function of scheduling and managing time.

What do raters receive or know about a game before the video arrives? Do raters receive information on the game along with the video? For example, could a publisher send along promotional or explanatory material for the rater?

PV: Along with the video, the only other information that might be provided to raters is a script or lyric sheet provided by the publisher for the game being evaluated. Capturing language and dialogue on the video submission, particularly in context, can be tricky. So sometimes, instead of having a video with a montage of several instances of foul language (including the most extreme), the raters review the scripts and lyric sheets to gain a better understanding of the dialogue and frequency with which profanity and other potentially offensive language occur. The written questionnaire that is part of the [publisher's] submission is used by ESRB staff to check the video and make sure that all of the pertinent content being described is appropriately represented in the video that raters review. If ESRB staff determines that the video is not representative of the written submission form (or vice versa) the submission is put on hold until the publisher corrects the deficiency.

Are raters allowed to read about games, for example previews in a magazine or on a website, before they rate them?

PV: We don't disallow it, and in reality it's unavoidable that some of them will encounter those kinds of things on occasion. However, we do stress that the raters should only consider the submitted materials put before them in assigning a rating.

If a game is a sequel, are raters required to be familiar with previous games in the series, either by research or by experience?

PV: The short answer is that it's not required. Games are rated individually based upon their content, not content that appeared in previous episodes or other versions in the series, so knowledge about prior games in a series isn't a necessity. However, that said, parity is a very important consideration. It's imperative that ratings be consistent, so there will be times that raters will review submissions from other games, in the series or not, to consider how similar content was previously rated when assigning a rating to a particular game.

Do raters have specialties in particular genres, as that might give them context for understanding what they're watching?

PV: The training that our raters undergo encompasses all genres, and they're abundantly exposed to all of them. As I said before, the particular games assigned to any rater are a function of scheduling more so than the individual qualities of the raters.

Given the detail in the videos provided by the publishers, are raters often avid players of the very games they've rated? That is, does the rating process spoil too much of the games to make them appealing?

PV: Of course one inescapable consequence of their job is that they will be reviewing game content before the rest of the world gets to see it. So yes, the raters are deprived of some of the surprise that everyone else gets to enjoy. But rating a game's pertinent content is a very different experience than playing a game for enjoyment. Raters are focused on very different things than someone who is playing the game to get from one level to the next.

Do raters tend to rate games that they enjoy playing?

PV: We rate over a thousand games a year. Some of those games are undoubtedly games that the raters like, and some are, I'm sure, games of which they're not the biggest fans. But whether or not they like a given game has nothing to do with the job they do each day. They approach content through the eyes of the average consumer and put aside their own likes and dislikes.

The raters for a game collaboratively determine a proposed rating and set of descriptors. Tell us about how that process has generally worked. Is it typical that raters have the same rating in mind when they get together to discuss a game they're reviewing?

PV: At each scheduled rating session, raters will watch the DVD or videotape together and then each writes down the rating he or she believes to be appropriate, before any discussion takes place. Each will then disclose his or her rating to the group, and discussion will ensue. After discussion, each rater indicates his or her final rating recommendation. As I'm sure you would expect, some games are very easy to agree upon. For example, you typically won't find much disagreement about an E-rated puzzle game. There are, however, inevitably going to be some titles that are "borderline" between two rating categories, and these generate more discussion and require greater deliberation on the part of the raters.

Truth be told, though, I'm just not privy to the conversations that take place when the raters are doing their job. We take the integrity of the process extremely seriously, and nobody else is present in the viewing room when raters are reviewing and discussing content.

How are disagreements among the raters resolved?

PV: Usually through discourse. They express their opinions about the content and recommend ratings to the group that they think are most appropriate, and they'll deliberate together trying to find common ground. They may review submissions for similar games previously rated by ESRB to help with the parity aspect. But ultimately, ratings are based on the majority consensus of raters, not on unanimous agreement, so it's not essential that all the raters completely agree all the time.

Along with a game's rating -- such as Everyone, Teen, or Mature -- it often receives what are known as descriptors. How contentious is the process of deciding a set of descriptors for a game?

Along with a game's rating -- such as Everyone, Teen, or Mature -- it often receives what are known as descriptors. How contentious is the process of deciding a set of descriptors for a game?

PV: Content descriptors aren't intended to be a complete listing of all of the different types of content one might encounter in a game. They are applied within the context of the rating category assigned, and are there to provide additional useful information regarding the content a consumer can expect to find.

But again, it's hard to make a blanket statement given the multitude of games we rate. Some games are pretty straightforward, and others require a more thoughtful and nuanced approach. We have a two-part rating system, and it would be fair to say that, at times, the assignment of content descriptors can be equally as deliberate as the assignment of a rating category to a particular game.

After the rating is assigned, the publisher may adjust their game to try for a different rating or appeal the rating. If a game is resubmitted, are the same raters used for the resubmitted game?

PV: The raters are scheduled based on availability and workload, not on what they've rated in the past.

Occasionally a game may receive a rating other than what a publisher might want. What kinds of changes do publishers make to change a rating?

PV: That's really up to the publisher, the type of content in their game and what rating they're shooting for. We provide guidance to publishers about elements that impact raters' determinations, but we never tell them what specific content they should or shouldn't change or how to do so. The content that goes into games is completely at the discretion of the games' creators. Our job is never to dictate content, but rather to evaluate it and assign a rating that we think will be helpful to consumers.

How frequent are appeals? A rough number would be nice -- say, N games out of every 1000.

PV: The appeals process has actually never been used, so the number you're looking for is zero out of 15,000 plus games rated! On the other hand, it's fairly common for publishers to revise and resubmit their games when they would prefer to release a game with a different rating than the one we assigned.

Ah, so no appeals. If there were an appeal, would the original raters be included in the appeal process, or is their original recommendation the only part they play into the appeal process?

PV: It's the latter. The appeals process doesn't involve the raters themselves. A group of industry members, retailers and other professionals would hear presentations both from the publisher and the ESRB, look at other materials they may deem relevant, and make a determination on whether or not the rating should stand.

The ESRB says that its raters are "trained to consider a wide range of pertinent content and other elements in assigning a rating." Could you elaborate on the kind of training the ESRB provides? Do raters get periodic training to keep them informed of the videogame industry and ratings of other games? Perhaps something akin to the continuing legal education courses that an attorney might take each year.

PV: The training we provide to raters is very intensive. It generally lasts from three to six weeks. It involves, but is not limited to, guided review of footage from past submissions; education about the types of content raters need to be on the lookout for; instruction on identifying screen elements that denote interactivity, and understanding how elements such as reward systems factor into rating assignments. They're put through mock rater sessions with games that were previously rated since, as I said earlier, consistency is important. And the training is definitely ongoing. After new or unique rating issues have been identified during any particular rating assignments, those issues are fully vetted with all of the raters as part of ongoing training by ESRB staff. And of course raters are constantly gaining more experience by virtue of rating games day in and day out.

Could you give us an example of a game whose rating process brought up particularly thorny issues, perhaps with both its rating and with its descriptors (which depend on the choice of rating). If you can't name a specific game, perhaps details about an example where raters had to work especially hard to arrive at a final rating and set of descriptors? What were the issues involved and how were the questions resolved?

PV: I can't speak to the rating process for any one game, but generally speaking, things like language -- bathroom humor, plays on words, slang -- fictitious or non-descript substances, or use of religious imagery can often be tricky. The presence of sensitive social issues in games, like sexual or racial stereotyping for example, have also led to internal debate about how best to address them from a ratings standpoint.

Though it might surprise people to hear it, low-level or cartoon violence actually tends to be something that receives a lot of thought and discussion. Take for instance an animated character that smacks another over the head with a frying pan. Is that Comic Mischief or Mild Cartoon Violence? To a degree, that's going to depend a lot on the depiction itself. What happened to the character when he got hit? How malicious or realistic was the violent act? How often does it occur? Context is also a consideration. What prompted the action? Is it player-controlled, or is it in a cut-scene?

Then, of course, the rating category figures in since the descriptors are applied relative to the rating assigned. Is this kind of content justification for assigning an E10+ or even a T, or is it still within an acceptable range for an E-rated game? The process we have in place and the people that are involved in it are extremely thoughtful about these kinds of things.

Some of your raters are parents. Are they instructed that they should think as a parent while rating games which their own children might play?

PV: We ask that the raters view content and assign ratings from the perspective of what they think would be most helpful to the average consumer, parents in particular. Our preference for hiring raters that have experience with children is so that they can apply that knowledge when considering content and assigning ratings that are intended to provide helpful guidance to parents.

Do raters apply their own moral standards (on subjects like violence, substance abuse, and sexuality) to guide their rating recommendations? Or, are they merely to apply a standard that the ESRB has set out for them?

PV: It's really a combination of both. Rating games is an inherently subjective practice in the sense that content is always going to be interpreted in different ways by different people. So part of the equation is the raters' own views on content, but as I said, parity and consistency play important roles as well.

Are those parents allowed to involve their children in the rating process?

PV: The submission materials that raters review are confidential, and they're strictly forbidden from discussing the content of those materials outside of the office. But we expect a rater's own life experience and the developmental experiences of their children to play a role in guiding their judgments, and we do not try to inhibit that as part of the rating process.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like