This article is meant to be a small collection of learned experiences from the paper prototyping process; it's a mix of tips, advice, and also a modicum of philosophy regarding the benefits of paper prototyping to assist with digital game design.

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

Oh, Sweet Sound of Paper Going ssschunk!

For some, it's the chirping of the birds and the wind rustling through the trees. For others it's the sun cresting over the horizon while holding a cup of freshly-brewed coffee. And for Robert Duvall in Apocalypse Now, it was a less-traditional “I love the smell of napalm in the morning!” Whatever it is, each of us has a “happy place” - something so core to our person that it fills a hole nothing else can. For me, it's the undeniably seductive lure of the paper cutter.

Actually, bollocks to all that. I hate the paper cutter! With a vengeance, even! When I think about paper cutters, my back seizes up like an engine with no oil, my hands cramp with memory pains, and my brain desperately tries to think of more enjoyable alternate activities like picking up the dog poop or visiting the dentist for an extra checkup. (Uncovered by insurance, of course.)

The reason? Simple: I've spent far too many hours hunched over the cutter making paper prototypes.

However, my loss is, with any luck, your gain. This article is meant to be a small collection of learned experiences from the paper prototyping process; it's a mix of tips, advice, and also a modicum of philosophy regarding the benefits of paper prototyping to assist with digital game design. The first part is about why paper prototyping is useful; the middle bit is about how to construct said prototypes; the end is a crash course overview of playtesting concerns.

|

| |

| ||

| “Me HEART Paper Cutter” |

A Short but Invigorating Exposition on the Fundamentally Beneficial Qualities of Leveraging Paper Prototyping to Increase Total Quality of Digital Entertainment Products. (In Other Words: Why You Should Paper Prototype)

Before jumping into specifics of prototype construction, a quick review is in order to establish why paper prototyping can be beneficial to digital game projects.

THE BIGGEST REASON

If you read nothing else in this article, understand that paper prototyping can save your project TIME and MONEY. I hardly need to wax poetic on the inestimable value of these two little guys, other than to say that they are the two items that can never be obtained in satisfactory quantities. (Unless perhaps you are Blizzard?)

The reason paper prototyping can save time and money is because you are able to start examining the gameplay of your game well in advance of large-scale coding and art asset production. You can do a creative and functional “check-up” to see if you are on the right track. If you are, great. If you aren't, then you can initiate needed design changes without having to scrap hundreds of man-hours of programmer and artist labor.

You can also find dreaded “problems.” Any problems in design cascade to the rest of the team. For sake of analogy, let's say programmers and artists are the large and small intestines. If so, then design problems are chicken with salmonella sauce. You get the TechnicolorTM picture.

Saving time and money is alone reason enough to prototype. My job done, I'm tempted to stop writing this section and go get some refreshments. But really, the fruity goodness doesn't stop with point number 1, as points 2 through 6 below will illustrate.Test Mechanics of Overall Game or a Game Subsystem

One of the most straightforward reasons to make a prototype is to test out the overall game mechanics. You put the wheels on your game and give it a spin, so to speak.

It's worth noting that you can make a prototype of an individual subsystem rather than the whole shebang at once. For example, some colleagues recently devised a prototype just to test out their game's combat system; the prototype was never meant to capture the “whole game”, but rather just a specific self-contained system. Other self-contained systems might be things like economies or reward structures.Test Balance

Similar to #2. In addition to “kicking the tires” of your game, you can also start putting the wax on--balancing. Any work you can do to balance early will pay off in later dividends.

Your project is “nimble” early on. Changes aren't that hard, which is in stark contrast to the terrible inertia that comes late in a project, where every change costs time, money, stress, and runs the risk of introducing cascading problems.

Take advantage of this temporary state. Iterate and improve.Test Flow

Although you have to be careful about the huge differences in game flow between the analog and digital mediums (see later in this article), a paper prototype can help test for good flow—after all, you are still playing the game even if it is in a different format.Test Fun

Sometimes a game can perform functionally, can be perfectly balanced, and can have a good flow, but it just isn't fun. This can be for a variety of reasons--maybe theme is dry or the player just isn't being challenged with interesting decisions. Whatever the reason, it's possible that you will detect this problem early, during paper prototyping. Again, changes are possible early, so it is the time to make them.Fill in Rules Holes

I'm always surprised at the rules holes that playtesting can discover. There's nothing like sitting down and having to set up your game and play it. No matter how hard you try to visualize, plan, and analyze beforehand, playtesting will seek out holes like water in a bucket you used for BB-gun practice. These holes may be simple structural holes, like you forgot an important step in game setup/initialization. Or, they might be strategy holes (dominant strategies, loopholes, etc.). Regardless, playtesting helps bring them to light.Jar Your Creative Juices

“Jar Your Creative Juices, Baby!”

By “jar your creative juices”, I don't really mean there is a canning and sterilization process involved.

There is a very nice side-benefit to the act of constructing and playing a paper version of your game or game system--it presents things in a new light. Looking at your project from a different perspective can aid your creativity. It is similar to other techniques in brainstorming and creative process. Chipping away at a problem from different sides helps to break logjams that look insurmountable from head-on. I almost always come away from my first couple playtest sessions with a ream of new ideas for the game. Some of them are even occasionally good!

The Limits of Paper Prototyping

Although there are some terrific reasons to make an analog prototype of digital game, there are also some inherent limitations to such a process. The first, and biggest, is that there are some games for which analog prototyping just doesn't make sense. Case in point, games where a real-time action component is the sole mechanic.

An example is Spider-Man 2. In the excellent postmortem featured in Game Developer (September 2004), the developers discussed how the webslinging mechanic was absolutely central to the enjoyment of the game, and how they wanted to improve on the control scheme of the predecessor. To that end, they constructed a digital, playable prototype very early on in development - much earlier than an operable build would normally be available. For this game, it's unlikely that an analog prototype would've been worth constructing (unless there was a subsystem to the game that deserved modeling).

Another example is Prince of Persia: the Sands of Time. The enjoyability of the game hinged on the fluidity of the player's movement; it was important that the swinging, wall running, and linked acrobatics functioned well. Like the other example, the team responded by making an early digital prototype that captured the flow and motion of the game.

Makin' Stuff

Ok, on to the nitty gritty!

The first and biggest tip for prototyping is a simple one: SCROUNGE. After all, the easiest way to make any game component is...don't make it! Ride the coattails of someone else, and pilfer bits with abandon. (I mean physical bits, not 1/8-of-a-byte bits.)

If you've got a game collection, pop open the boxes and look for tokens, dice, markers, and other pieces that might serve a need. Just remember what you take, so you don't end up in a situation a few months down the road where you have a table full of people rarin' to go for an Axis and Allies game and then you suddenly realize you don't have two tanks to rub together because you “borrowed” them all for your Wildebeests vs. Wehrmacht prototype you cobbled together in a fit of misguided inspiration one lazy Sunday when the air conditioning was failing. Been there, done that!

A great source for spare parts is your local thrift store. There are usually many board games to be had for only a buck or two each. And some are actually worth it! Also, if the weather is good, look for garage sales and the like.

|

|

|

| ||

| “The Fruits of Your Labors – A Functioning Prototype!” |

If your prototype needs a board, old cruddy board games fit the bill nicely—usually the boards are nice, sturdy chipboard. You can print out your own game board on normal paper and then just spray fix it or tape it onto the sacrificial board. I'll talk more about boards later.

A last note about scrounging: don't stop at games. There are a surprising number of household items that can serve as game components. Stores like Pier 1 and the like usually have a good selection of potential game parts, too - decorative items like glass beads, polished rocks... whatever. Basically, just keep your “eyes” on every time you're in a store. You'll start to see game innards all around you, and this doesn't necessarily mean you need therapy.

Another source for good potential game parts are the toy aisles at supermarkets, Target, and the like. There are usually little packaged assortments of vehicles, toy soldiers, farmyard sets, etc., that can be an inexpensive boon for the practicing designer. Earth only knows how many Toy Soldier homebrew games there are out there.

A lot of the above might just sound like common sense... and it is. Just be resourceful, and you can keep the amount of work to a minimum by preventing the need to custom make every part of your prototype.

Rollin' up Yer Sleeves

When it comes down to it, you often can't avoid some actual layout and assembly time because you will need very specific items for your game. The most common - “the big hitters” - are cards, tokens/counters, and gameboards.

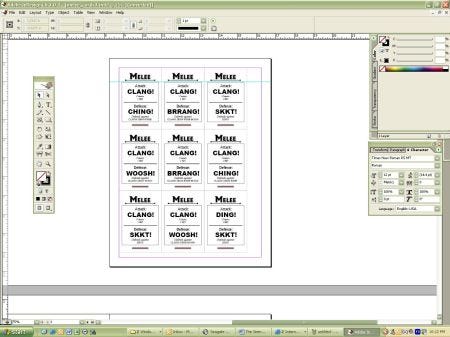

Cards

Many, many games feature a mechanic that involves cards. Even though you are prototyping a digital game, cards can be used to recreate many mechanics involving a random draw element - events, treasure finding, monster encounters, and the like. Although dice are obviously the cat's meow as far as representing abstract randomness goes, sometimes cards are better for specific random applications. For instance, if there are 20 possible events that can happen to the player, you could use a 20-sided die and a look-up table in your prototype, or you could just make 20 event cards. Is one event more common than others? Easy, just make more than one copy of that event card and seed the deck appropriately to get the distribution you want.

With the usefulness of cards comes, sadly, a difficulty factor that is commensurate. Cards can be some of the most backbreaking and frustrating components to make - that is, unless you know a couple tips to make your life easier.

Cards are tricky for prototypes because often you need the cards to stand up well to wear (repeated playtests) and also you usually need them to shuffle well. Shuffling well means that the cards need a good weight to them and they also need to have very precise edges - uneven cuts result in “trick decks” where certain cards catch on your fingers more than others. These “trick decks” are also known as “shoddy workmanship” decks, and “my 6-year old uses scissors better than you” decks. At least that is what they are referred to in professional circles.

There are a lot of different ways to make cards, but so far the very easiest I've found is this:

Lay out the cards using your program of choice. Certainly, if you are a closet graphic designer or artist, use InDesign, Quark, Illustrator, or even Photoshop to mock-up your cards. However, don't fret if you aren't of that persuasion—you can make very serviceable cards just with MS Word. Check out the DRAWING toolbar.

Standard playing card size is 3.5” x 2.5”. That's a nice, comfortable size that can fit a lot of content and has a good aspect ratio and a feel people are familiar with. You can fit 9 to a 8.5” x 11” page when mocking up—three rows of three.

If you don't have a lot of content, don't be afraid to do a smaller size card. You probably want to keep the same aspect ratio as the standard size, but not a big deal. A smaller size card means you might be able to fit more cards per page, which makes life a bit easier production-wise.

Make sure to include the card borderlines on your template. You'll be cutting to them. (duh) You don't need to allow any room between card edges—just butt them up right next to each other.

|

|

|

| ||

| “Cards, Cards, Cards” |

Print the cards out. Use standard 20-24 lb. multiuse paper. There's no need to use 110 lb. cardstock or thicker, because of what you'll do in step 4. If you want card backs, just print the card backs out as their own sheet(s). Don't bother duplexing and trying to line the card backs up with the card fronts on a single piece of paper. It's a royal PITA and you really don't need to do it (see step 4).

Cut the cards out.

The absolute best tool you can use for this is a rotary paper cutter, such as the ones Dahl makes. A rotary paper cutter is more accurate and has better motion than a guillotine paper cutter. The guillotines can pull your paper as they cut, especially if the blade is rather dull or you are cutting more than one page at a time. Scissors work, too, but are even less preferable than the guillotine because they take longer. So, think of the three cutters as forming a transitive relationship (for you game mechanicians out there): rotary > guillotine > scissors.

Don't worry about being exact in your cuts. This is a huge deal, and will save you tons of time! This will be ok, because...

Place your newly cut cards into card protector sleeves. These sleeves can be purchased from any specialty games retailer, and also from some mass-market stores. The sleeves are used by collectible card game players to prevent Cheetos and Mountain Dew from sliming their Magic and Pokemon “investments”. I use Dragonshields, but UltraPro makes a selection of card protectors as well. You want fairly sturdy ones—some cheaper card sleeves are so thin that they aren't very good. Using the card protectors serves three important purposes:

Promotes shuffling by adding extra weight to your paper cards.

Promotes shuffling because the card sleeves are all exactly the same size. Your jagged, unevenly cut paper cards sit inside, and don't screw up the perfect geometric consistency of your finished deck. Ah, as Einstein said, there is symmetry in mother nature after all.

Prevents Cheetos and Mountain Dew from sliming your prototype “investment”.

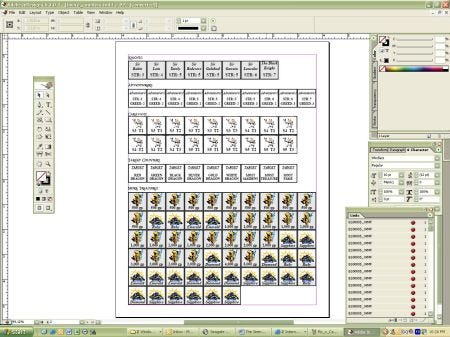

Counters/Tokens

Counters and tokens can be almost as maddening as cards; actually, they are really more maddening because cards get pretty easy using the above procedure.

Counters and tokens should be laid out similar to cards. However, a few layout tips:

Good token sizes are 0.75” square. 0.5” square starts getting pretty small. 1” square is great if you don't have too many tokens or if you have plenty of room on your gameboard. Bigger than 1” square is only really good if you are doing something special with your counters/tokens that requires them to be “bigguns.”

I tend to butt all counters of a common group up right next to each other. But I put some page space between different types of counters. A bit of space will help during cutting (see step 4). If you've ever seen die-cut counter sheets in boardgames you buy, arrange like that.

Print the counters on normal paper or on 110 lb. cardstock. Then you really need to affix the paper to something heavier. There are two great options here, depending on your tolerance for stinkiness...

“The Stinky Option”. Go to your local DIY home improvement store and purchase some of the cheapest self-adhesive linoleum tile you can find. Buy the 12” x 12” size, which can usually be found for less than $1 each. Now, remove the adhesive liner and press your printed sheet down onto the tile. Press it down nice and evenly and try to avoid air bubbles—use a brayer if you have one (artist speak for tiny little roller). Linoleum tile has a terrific weight and feel and is very resilient to handling. Sadly, the adhesive is, well, STINKY! When you have your prototype out, expect people to give you looks, that seem to say “What is that cheesy smell?” You need to develop some convenient ways to drop an explanation into casual conversation and thereby exonerate yourself from embarrassing social faux-pas. I recommend such subtle cues as “Heh...man! Isn't this prototype stinky? It's the linoleum tiles. The epoxy or somethin'. Ick!” Repeat this to every passer-by, and over the company intercom if necessary. Or, don't explain and suffer the shame. As game designers, we must take one on the chin for the good of the game sometimes.

“The Non-Stinky Option”. Use spray adhesive to mount your counter printouts to matboard. Matboard is relatively cheap—especially if you can buy damaged sheets or sheets with visual flaws (which don't matter to you). Matboard is very durable and not toooo hard to cut. Another option is foam core, although that is harder to cut overall.

Regardless of which of the above two backing materials you used, now use a hobby knife and a steel rule and cut out your rows of counters. Use a sharp blade, and try hard not to perform any inadvertent amputations. It's easy to get careless while cutting out counter row #26. So stay alert and don't bleed on your nice print job. Once you've cut out your counter rows, I find the easiest way to cut out individual counters is by using scissors. A good pair of scissors is up to the challenge of a series of 1” cuts; they just don't work well for cutting the initial rows out. When you're cutting with the scissors, you'll find that sometimes it causes the counter edges to curl up a bit. Experiment with placement of the counter on the scissors blade—you can find a sweet spot where the cut is still possible (doesn't require too much force) but the counter doesn't really get curled up.

|

|

|

| ||

| “A Sheet of Counters is A Sheet of Counters by Any Other Name” |

Boards

Ok, boards are the last of the Big 3. Boards are a bit funny because there're many different ways to make them, and it's heavily dependent on your available resources and technology. Probably the best option is to print out your board in one piece on a large format plotter, preferably color. Since most of us don't have access to those, perhaps because we no longer work for engineering companies where we can slip an extra print off now and again, a more common option is just print your gameboard out in tiled format. Regardless of which way, your next decision is whether to mount your board or not. There's no need to—you can always playtest with simple paper printouts. Not mounting the board also means that changes can be made and then you just hit “Print” and you're back in action again. If you do decide to mount, probably your best option is to reuse a board from some cruddy board game you find at a thrift shop. They're all set-up to fold and everything! Other options are matboard and foam core.

An altogether separate option is to just draw your gameboard and eschew the computer altogether. This really comes down to preference. If you are a pencil and Art-Gum TM type, or a drafting lead and engineer's scale type, then go for it. Also, sometimes drawing your own board can simply be quicker than using a com-pewter. I only draw boards manually when I am in a huge rush or delusionally tired, but that's just because I have “limited artistic ability”, which is a euphemism for being a crappy drawer.

|

|

|

| ||

| “A Perfectly Suitable (if ugly) Hand-Made Board” |

Super-Secret Clandestine Game Construction Resource: The Board Game Designer's Forum

Although I've shared some of my own tips on paper game construction, a great resource for other tips and opinions is the Board Game Designer's Forum: www.bgdf.com. Truth be told, I avoid the site for the most part - not because it's not useful (it is!). It's just that there are so many good tips to be found, it can be a bit... distracting. Plus, I don't like to expose myself to a million other design ideas while I'm in the midst of gelling a design. It really is a good site, though.

Gathering it all Together

Organizing your prototype and containing it is important to make your life easier and also to make it portable. I use fishing tackle boxes and map/poster tubes. You can find little tackle boxes for cheap at the K-Marts, Targets, and also at certain unnamed ginormous superpowerful mega-corporations of the world that begin with the letter “W” and are based out of Arkansas - a strange state whose name is pronounced quite differently than appearance would seem to insinuate. (A name which is exceptionally confusing when taken in context with the nearby state “ Kansas ”, pronounced “Kan-saw” to some.)

Other Considerations: Looks Good vs. Tastes Great

The great Aesthetic Dilemma. Having a sexy prototype improves play experience. However, you might find you spend more time prototyping and not enough time playing. Also, making a stunning prototype might reduce your willingness to make necessary changes that would require you to dismantle your lovely creation.

Also, there's a school of thought that says “if they enjoy playing your terrible, ugly, lame prototype, then they will LOVE it when it is jazzed-up.” Well, that's how I rationalize it anyway.

Playtesting

|

|

|

| ||

| “Playtesting - Let's Put Some Lipstick on this Pig and See if it Can Dance!” |

Playtesting is a huge subject in its own - too big to cover exhaustively in this article. However, here are some key tips to bear in mind:

Have an idea of what outcome you'd like out of the playtest session.

This can be broad (“I'd like to see if the game is ‘fun,'” “I'd like to see what the flow is like.”) or it can be narrow (“I'd like to see how the game plays with 2 players,” “I'd like to put the psychic combat system through its paces.”). Whatever it is, just have a goal. Otherwise, you might have a waffling, undirected playtest session with no concrete deliverables or quantifiable outcome.

Be prepared to write.

Sounds dumb, but be prepared to record feedback, “bugs”, and data. It's easy to get so focused on getting the prototype made and set up that you don't focus on prepping to get the most out of the session(s) possible. If necessary, have an extra helper to act as secretary and record important information, so you can focus on administering the game.

Be prepared to adjust in real-time.

Almost every time I do a first playtest, I'm amazed by how different something in the game is from what I predicted. Also, even though I've gotten better and better and drafting rulesets, there's nothing like the first time you set up and try to play through a game - you are guaranteed to find holes in your rules. I'm not talking about degenerate strategies or anything fancy; rather I mean true show-stopping holes, like “oh, how does that work?” In any case, be ready to plug holes, make rules changes, and otherwise mold your game on-the-fly.

Case in point: I just finished up a prototype for a board game which involved a particular mechanic that I was quite proud of, one that I conceptually believed to be a huge part of the game. On turn 2 of the very first playtest, I realized the mechanic was 500% better in my head than in practice. Accordingly, I could instantly tell the game was going to be a bust unless I removed it. So remove it I did, right then and there during the very first playtest. The game immediately improved, and I realized it could stand on its own without the Golden Mechanic. Adjust on-the-fly.

Be impartial.

Playtesting is one of the absolute best things you can do for your game - don't corrupt the information you get by arguing with your playtesters. Listen to them. They aren't necessarily right, but they will provide honest feedback. They haven't been living inside of your head, and they don't know how great your game could be. They only know how great the game is.

“Know” your playtesters.

If your game is hard-core strategy aimed at the professional gamer, don't waste much time having a casual gamer play it and tell you how complex and confusing it is.

1st playtest vs later playtests.

A last thing: the 1 st playtest for a game is a whole different animal than later playtest sessions. For me, the goal of the 1 st playtest is to successfully get the game set-up and played through. It's like casting a wide net and seeing what kind of fish live in a particular stretch of water. Later playtests are hunts for specific fish.

Don't expect your first playtest session to be fun. You might spend the majority of your time just plugging hull-breaches and trying to keep the game afloat. There's an old adage in the kit-plane industry: don't schedule your first flight test to be a party or social event where all your friends and family come to see all your hard work pay off. Save that for after you've got the kinks worked out. Don't put any more pressure on yourself than necessary. Your first playtest session is about rolling up your sleeves and hopping into the ring. You might not be photogenic after getting drubbed by Clubber Lane for 10 rounds, so don't plan an evening gala.

Playtesting NDAs

Remember the legal forms. Non-disclosure Agreements are vital for all involved.

Review forms

The more you prepare for your playtest session, the more value it will yield. Preprinted review forms are a great way to get meaningful feedback from testers.

Yes, a lot of this is just like focus testing, so many of the same tips apply.

|

|

|

| ||

| “A Victim...err ‘Assistant'... is Always Helpful” |

Off to the Guillotine with Ye!

When it comes down to it, paper prototyping can almost always provide benefits to your game development that far exceed the effort, cost, and time involved. The worst that is likely to happen is that find you're well on-track with a good design. The best that could happen is that you prevent crippling changes from occurring late in the project. There might be no faster way to becoming a social pariah in your company circles than the words “Late Design Change.”

Much of prototyping is common sense, and can be boiled down to 3 easy steps: improvise, adapt, revise. So what're you reading this for? Get cutting!

|

|

|

| ||

| “Infect the Towns of the World with Your Plague Prototypes” |

______________________________________________________

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like