PAGAN: Autogeny casts the player out into the digital ruins of an abandoned MMO, freeing them to wander a once-living online world that now sits in lonely silence.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

PAGAN: Autogeny casts the player out into the digital ruins of an abandoned MMO, freeing them to wander a once-living online world that now sits in lonely silence. Through its melancholy places, it aims to explore a sensation of wandering a once-thriving landscape and the emotions that are stirred up by it.

Gamasutra spoke with Oleander Garden, sole developer of PAGAN: Autogeny, to learn about the feelings that were stirred up in creating a purposely dead gaming world, how dead MMOs can feel like abandoned malls, and the melancholy that comes with visiting our old, empty digital homes.

Worldbuilder

I'm Oleander Garden — or at least, that's the pseudonym I publish my work under. I was the (lone) developer of PAGAN: Autogeny.

I started out modding — first just little XML tweaks, and eventually, larger projects. The first basically coherent games I made on my own were wildly over-ambitious, barely functional ASCII RPGs. Eventually, I wanted to start doing more visually interesting work, so I switched to making games in Unity. Most of this stuff never got circulated outside my immediate circle of friends, though. I only started posting things online in mid-2018 in anticipation of the PAGAN Trilogy.

MMO-making equipment

Unity. Nothing too interesting, unfortunately.

Coming up with the concept for PAGAN: Autogeny

I've been stuck on this question for a while. Truthfully, I'm not sure! There was never a conscious moment of conception; everything unfolded gradually.

Memories of digital landscapes

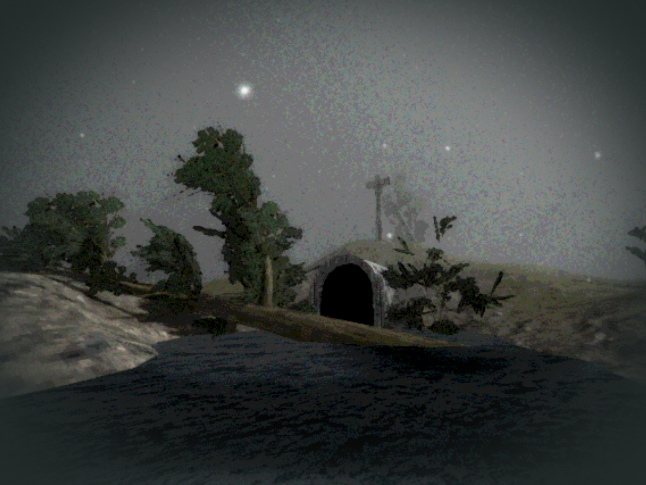

MMOs are really weird. At their best, they transcend the normal boundaries of 'games', and become spaces that we dwell in; places where we interact with each other. They're like little digital plazas. So, what happens when you take that social dimension away? What sorts of things get exposed when only the scaffolding is left? And, crucially, what do we leave behind once we're gone?

Everyone has memories that are bound up in the places that we used to live, and likewise, I suspect everyone who grew up online has memories bound up in the digital landscape we used to inhabit. And it's always a strange feeling, right? To come back to those sections of cyberspace and to find them completely abandoned — or at the very least, completely transfigured. PAGAN: Autogeny reflects my interest in that sort of experience: the strange melancholy of seeing your old 'home' in ruins.

On creating a vast MMO world

The hardest part was faking it! PAGAN: Autogeny feels a lot bigger then it actually is. But the world is so circuitous and winding, and you pass through so many different environments, that you start to get an outsized sense of scale. This sort of world design — filled with twisting corridors and weird warp gates —is perfect for hiding secrets. Any object can obscure new passageways - new strange worlds. So, it's mostly smoke and mirrors; but then again, when are videogames not smoke and mirrors?

The feeling of spaces we used to inhabit

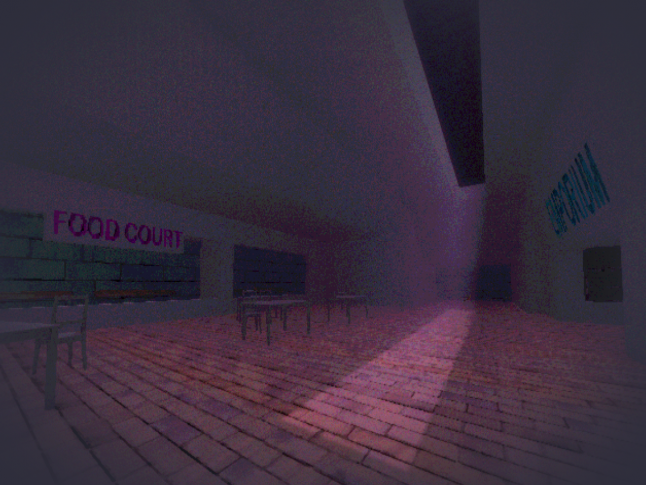

The situation of a dead MMO is comparable to the situation of (e.g.) a dead mall. These are spaces that people used to inhabit and dwell in, and which embody a particular approach to social life that is no longer present or active. When we find these places in decay, we are reminded of what we have lost, and become acutely aware that we can never go back.

But (if I can hazard to a little addendum) I don't think it's purely an experience of dread. Our encounter with these kinds of spaces also makes us acutely aware of what we have gained: of what these place did for us, how they shaped who we were, and how they made us who we are today.

Unwelcoming worlds

Unwelcoming worlds

PAGAN: Autogeny is secretly an adventure game masquerading as a first-person RPG. Fundamentally, it isn't about reflexes or mechanical skill or leveling up; it's about working out the logic of this strange world, and figuring out how everything in it fits together.

To that end, I ripped a lot of design ideas from old point-and-clicks and top-down adventure games, which often functioned similarly. Shadow of the Comet (1993), and Ultima: Martian Dreams (1991) are two good, relatively well-known examples. These sorts of games created a world that seemed to exist for its own sake, with its own internal logic. You—the player—were an unwelcome interlocutor, rather then the center of attention. In a sense, they embody the opposite of contemporary power fantasy design, which centers agency and player choice. These old games said: No, there's a world which precedes you, and you're going to have to figure out how to work with it. I think there's something basically admirable about that.

On the feelings stirred up by creating a dead game world

It was even stranger than that: while I was making PAGAN: Autogeny, I had two dozen twitter followers, and my free games had accumulated maybe 50 downloads each. I was expecting to sell five or six copies. I was making—as far as I was concerned—a dead game about a dead game!

So, I found creating PAGAN: Autogeny to be a largely cathartic experience. I got to spend eight or nine months with this weird game that seemed to exist purely for its own sake. It was a way of engaging with ideas of self-creation and social identity (which the game seems to orbit around) in a sustained and unstructured way—at a time in my life where that was, incidentally, extraordinarily useful to me. It didn't need to be a marketable product: it was simply what it was. So, although the subject matter is perhaps a little bleak, my encounter with the game has always been, and remains, very positive.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like