A Mortician's Tale explores death and the stories and emotions around the deceased through having the player work in the death industry.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

A Mortician's Tale explores death and the stories and emotions around the deceased through having the player work in the death industry. Through speaking with the deceased's family, learning their stories, and carrying out the embalming process, players will come to know the dead who come their way, learning stories of life, joy, and sadness through their work.

Gamasutra sought out Gabby DaRienzo and Andrew Carvalho, developers of the Excellence in Narrative nominated A Mortician's Tale, to talk about what they wanted the player to feel through taking on work in the death industry, what they wanted them to learn about coping with death and grieving, and how they conveyed all of this through the game's narrative and play.

What's your background in making games?

DaRienzo: My background is in graphic design. Shortly after graduating school, I got my first job working on the marketing team for a mid-sized game studio here in Toronto. After a year or so of working in marketing, I transitioned into doing game art and UI/UX design for the studio’s games team. I did that for a few years, but at a certain point, I wanted to work for other independent teams, as well as make my own games too, and couldn’t do it while employed at that studio... so I left!

I’ve been freelancing as a game artist for a few years now - most recently working for the teams behind the games Celeste, Parkitect, and Graceful Explosion Machine - and in 2016 I co-founded Laundry Bear Games with Andrew (Carvalho). A Mortician’s Tale is our debut game as Laundry Bear.

Carvalho: I didn’t really think about making games until I was almost done school. I studied computer science, and near the end I made the connection that I had spent so much time playing and discussing games and also had the skills to make them. My first job in games was porting iOS games to Android in the early days of smartphones. After that, I got my first job working in indie games as a developer on Sound Shapes. After its release, I moved into doing freelance and have since worked on a wide variety of games on console, desktop, mobile and most recently VR, as a developer on the game Blasters of the Universe.

For the past couple years I’ve also been teaching at Sheridan College in the game design program. Starting a studio is something I’d been planning since I left school, but very quickly realized I had no idea how to run a studio and thought it best to learn by observing while working for others. Finally feeling comfortable and finding a solid partner with similar design values, Gabby (DaRienzo) and I founded Laundry Bear a few years ago.

How did you come up with the concept?

DaRienzo: I have a few friends who either currently or have previously worked in the death industry. I’ve always been interested in their work, and knew I wanted to make a game inspired by their experiences, but it wasn’t until after reading Caitlin Doughty’s book Smoke Gets in Your Eyes that I felt motivated to do it.

Smoke Gets In Your Eyes is a fascinating, and often humorous, autobiography where Caitlin talks about her career as a mortician and the history of the western death industry. I really loved Caitlin’s story about going from working in a crematorium, to attending funeral direction school, to running her own green funeral home, and that heavily inspired the story of A Mortician’s Tale.

I was also introduced to the concept of “death positivity” through Caitlin’s book, which sounds like a bizarre term, but it’s a movement that encourages people to be open to talking about death, and to explore their fears of grief and mortality. It’s not meant to erase feelings of grief or loss, but to instead be open to understanding it, and discussing it. Ultimately being comfortable with talking about death allows us to make informed decisions for both ourselves and our loved ones when we/they die.

This idea of death positivity really resonated with me, and I wanted to develop a game in which players are encouraged to directly interact with the often uncomfortable topics of death and grief, with the hope that they would learn something about themselves, and the Western death industry, in the process.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Carvalho: The original prototype for A Mortician’s Tale was made by Gabby in PICO-8, but we knew we would have to move away from that tool to accomplish what we wanted with the game. Though Gabby and I have worked with several tools and I had shipped games using everything from XNA to C++, we both were comfortable with Unity as we had both been using the engine since shortly after Unity 4 was released back in 2012. Most of my work in games for the past five years has been in Unity, so I’ve built lots of tools throughout the various projects. It made sense to leverage them and stay with the tool that was most comfortable.

Gabby made all the models and animations in Blender. I have always used Visual Studio with Unity as it’s my preferred IDE. For project management, we used Trello, and Google Docs was the easiest collaborative tool to use for our team, so that’s where most of documentation and script writing happened. We also made the decision to use FMOD shortly after their license revamp made them a much more viable option for us, and Robby Duguay, our technical sound designer, was already familiar with the tool. It took a fair amount of work off my plate as the programmer and it was really the best decision.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

Carvalho: The entire project, from proper start to end, was about a year and a half, though Gabby and I were both managing other full time amounts of work on the side. Gabby was working with Vertex Pop, Will O’Neill, Matt Makes Games, and Texel Raptor. I was working with Secret Location as well as teaching at Sheridan College. We would end up working on weekends when we could, but with such a full schedule, it was definitely something we ended up taking our time with and pushing on when we had some free time between contracts or semesters.

If we had worked on the project full time, we expect it would have been closer to six or eight months. We both believe, however, that if we hadn’t taken as long as we had, we wouldn’t have made the same game. The time between pushes allowed us to reflect on what we had built and really focus on making A Mortician’s Tale what it would eventually become. It’s a workflow we enjoyed and are using again as we work on prototyping our next project.

How did you create gameplay out of a mortician's work? What challenges did you face in doing so?

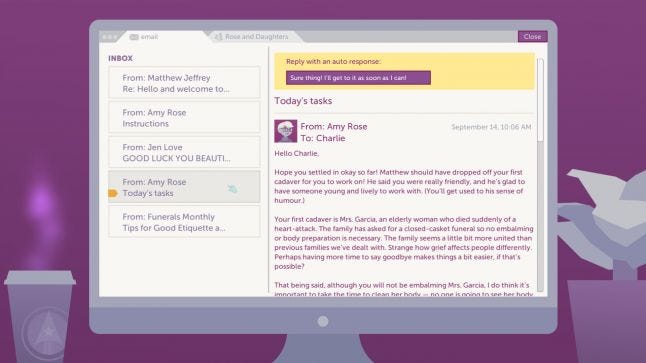

DaRienzo: We consulted with several funeral directors when developing the game, and learned that the majority of their job actually involves interacting with living people - making arrangements with the family, consoling the deceased’s loved ones, interacting with other coworkers and professionals in the business. We wanted to make sure we emulated that in A Mortician’s Tale, and so the majority of the game is quite narrative-focussed: interacting with the protagonist’s email client, learning about their coworkers, bosses and friends, attending the deceased’s respective funerals and listening to their loved ones’ stories.

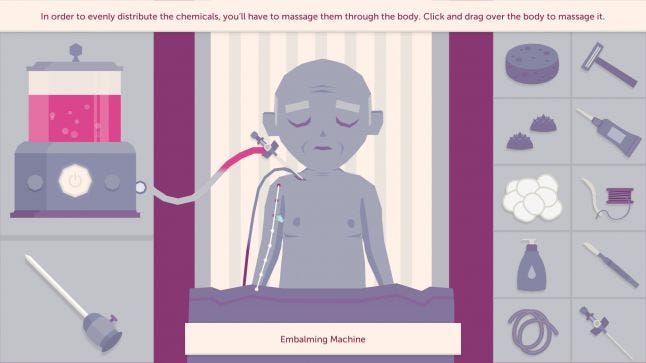

A Mortician’s Tale’s medical scenes, however, are designed to encourage players to learn about the subject matter through play. In contrast to other medical games like Trauma Centre that use a timer, score, and fail states to recreate the sense of urgency that a surgeon would have in real life, we tried to do the opposite with A Mortician’s Tale. There is no score, timer, or fail states, putting more emphasis on the lack of urgency a funeral director would have in real life, taking the time to care for the bodies of the deceased, and not allowing the player to disrespect the body at any point.

The biggest challenge for us was finding a balance between realism and comfort. It was important for us to make sure we were as accurate about the subject matter as possible, while also being aware that it’s very uncomfortable for many. Every decision we made while developing the game - from its muted, purple palette, to its restrictive mechanics - supports this balance, and aims to make the subject matter more digestible for all players.

What do you feel is special about the unique character narratives of A Mortician's Tale? About learning about the deceased through family stories and the time spent preparing their body?

DaRienzo: One of our goals when developing A Mortician’s Tale was to ensure that we didn’t just show “sadness”. Grief is so different from person-to-person, and embodies a whole spectrum of different emotions. A Mortician’s Tale lead writer Kaitlin Tremblay did an incredible job at exploring this, and showcasing different types of grief - sometimes it’s sadness, but sometimes it’s sharing happy stories about the deceased, sometimes it’s laughter, or rage, or sometimes it’s just conversations with your friends about what the weather has been like, or what shows you’ve been watching on Netflix recently.

While consulting with our funeral director friends, I asked if there was ever a body they couldn’t handle, or had to pass onto another coworker. Every single one of them said yes, and while I expected it to be for a gross, body-related reason, they were all actually related to the story behind the deceased. Even though the procedure would be the exact same as any other client, because the mortician knew about the deceased’s backstory, preparing their body was much more emotional for them. This ranged from things like the deceased not having family, or being a child, or sharing similar backstories as our mortician friends.

I thought this was extremely powerful, and wanted to make sure we explored this in A Mortician’s Tale. The medical scenes are no different body to body, but there are particular narratives for specific bodies in the game that are much sadder or more personal than others. We’ve noticed that some players tend to take extra time on these bodies, and give them extra care, even though the mechanics are literally no different than any others. It’s really moving to see players treat the game with such decency.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

DaRienzo: This is a bit of a cop-out answer, but I did a bunch of artwork for Celeste, so that’s of course on my list [laughs]. The team did such an incredible job with that game and I can’t wait for the world to play it.

There are a ton of games that came out in 2017 that I absolutely loved like Tacoma, Butterfly Soup, and Night in the Woods. I lost my mom to breast cancer early last year, and NITW was tremendously helpful in my grieving process. The characters are incredibly well-written, and Mae’s mother was so, so close to my own mom, which I appreciated.

Carvalho: I’ve played Getting Over It and thoroughly enjoyed it. I’ve taken advantage of the fact Gabby was working on Celeste and so I played a fair bit of it. I’ve been a sucker for Matt’s platformers for a long time, skipping class playing MoneySeize back while I was in school. I’m very excited for what he and Noel have put together with the rest of the team. I’ve avoided Cuphead because it’s definitely the kind of game that I won’t put down until I master it and I just haven’t had the time commitment to risk starting. Shenzhen I/O is an obvious one; being a programmer it definitely scratches an itch for me. I’m probably most excited to try Baba Is You, which I’ve been smitten with since I first saw it. It’s one of those game ideas you see and think ‘this is probably more clever than anything I will ever come up with.’

What do you think are the biggest hurdles (and opportunities) for indie devs today?

DaRienzo: With free and easy-to-use game-making tools and resources becoming more widely available, and with several open marketplaces to widely distribute games, we’re seeing more and more diverse creators of different creative backgrounds making very fantastic games that wouldn’t have existed maybe 5 years ago. That’s super exciting, and the games space is becoming much better and much more interesting because of this.

On the flip side, because more and more people are able to create and distribute games, there is a lot more work needed to make sure your game stands out from the crowd. We can no longer rely on store algorithms to advertise games, and indie game developers need to take their marketing seriously. A major part of my job at Laundry Bear is doing the marketing for our games, and I think it’s a very important role that all teams need to consider right from when they start developing their games.

Carvalho: I agree wholeheartedly with needing to do more to stand out. That also comes from the technical side as well. Having accessible game tools means what used to be impressive is now out of the box functionality that everyone has access to. I’m seeing more and more artists and developers grow past traditional roles to fill in gaps in the game development process. Working as a technical artist or rigger or having someone dedicated to optimization is slowly becoming the standard, even for small teams. This industry has always required people to continue to learn and grow, and that has become more important in today’s development landscape. Seeing how varied a small game developer’s skills needs to be now compared to just 10 years ago is both awe inspiring and scary.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like