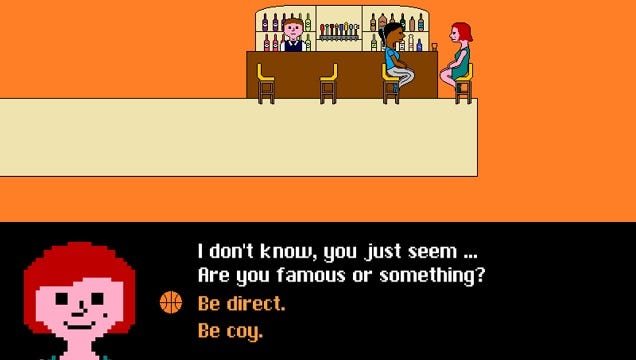

Watch Me Jump turns a play of the WNBA into a piece of interactive fiction, having players shape a life and career through the choices they make for Audra, an all-star player rocked by scandal.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

Watch Me Jump turns a play of the WNBA into a piece of interactive fiction, having players shape a life and career through the choices they make for Audra, an all-star player rocked by scandal.

Gamasutra sat down with Jeremy Gable, developer of the Excellence in Narrative-nominated Watch Me Jump, to talk about the similarities between theatre and games, how he took a play about the WNBA and made a game of it, and the importance of having imperfect choices in interactive fiction.

A playwright into a developer

I’m Jeremy Gable, Philadelphia-based playwright and game developer. I created Watch Me Jump, which included the story, artwork, music, and most of the programming, as well as having written the play on which it’s based. So basically, my role was “I made it.”

Before this, my background in making games was absolutely nothing. Unless you count the time when I was 10 years old and I mapped out a full design for a video game adaptation of An American Tail: Fievel Goes West on notebook paper. Which I don’t.

Inspirations to turn a WNBA play into a game

About four years ago, I’d wanted to write a play about the WNBA, but I didn’t know what the story would be until I read about two players, who were engaged to each other, who were arrested for assault and disorderly conduct. And this was around the same time an NFL player’s domestic violence dispute was caught on video and leaked to the Internet. Those two events sent a bunch of ideas swirling in my head. A couple of months later, I had written the first draft of a play.

When it came to Watch Me Jump as a video game, that decision was made a couple years later, after my umpteenth playthrough of Undertale. Since I would have to learn a whole new set of skills in order to make my own game, I figured it would be more practical if I already had a story in place. So I looked at the script for Watch Me Jump, and I realized that not only would it be a fun challenge for me to figure out how to adapt it into an interactive narrative, but it would be an opportunity to create a story that had never been told as a game. A year later, I released Watch Me Jump. And the world was never the same. Except for the parts of the world that stayed the same.

The means to make a basketball narrative game

I used GameMaker Studio for the programming. Gimp for the artwork. LMMS for the music composition. Audacity for the audio editing. Repeated listening of the soundtracks to Undertale, Her Story, and Gone Home for the inspiration. Tea and Excedrin for the caffeine. Constantly yelling “Why didn’t that work” at my monitor for the catharsis.

Finding common ground between games and theatre

For several years now, I’ve felt that the worlds of theatre and gaming have a lot in common. You can turn on a movie or play a piece of music and walk away from it, but both a piece of theatre and a video game require at least one person to interact with it, to both experience and shape that singular performance or playthrough. And with each, no two experiences are the same.

As a playwright, I’m always considering the relationship between the story and the audience. And that translated to game design, as I was constantly asking myself how to engage with the player. Also, I love the rhythms of language, which became essential in programming the beats and cadences in how the game’s dialogue played out.

Exploring people trying to do what they think is best

The themes for the game? Basically everything that was bouncing around in my head when I was researching the story. A lot of thoughts about sports, violence, celebrity culture, sexuality, legacy, loyalty, dependency, and pay disparity. I also wanted to create a narrative where it was difficult to choose sides, a story where “good people and bad people” are replaced by a group of individuals who are trying to do what they think is best.

I also wanted to make a game where you try to say “Do you know where I can find a good pizza restaurant” in Russian. So, you know, mission accomplished.

Shaping a person through choice

It feels like a lot of narrative-based games are concerned with action, constantly asking the player, “What are you going to do?” When deciding how to make Watch Me Jump into a game, I wanted to try something different by giving the player a series of pre-determined actions and asking them, “How do you want to react?” Depending on the player’s choices, Audra can run the gamut from apologetic to assertive, from vulnerable to confrontational. So rather than shaping an event, you’re shaping a personality.

The challenges of moving away from theatre and into interactive fiction

Well, the first challenge was actually being able to implement a branching narrative into the game. Fortunately, I received some much-needed help through a wonderful GMS dialogue engine with the not-at-all-weird name of Frilly Knickers, which was created by Juju Adams. Then, I had to figure out just how the narrative split off, which is when I decided on choices that altered personality rather than action.

What made it different from writing a play was that as a playwright, you have to make a choice. When I wrote the original story, I made my own decisions for Audra at every step of her journey. But in creating the game, I went back and tried to figure out just how many different versions of her I could make. It was like creating different parallel universes to the play, in which there was Diplomatic Audra, Rude Audra, Considerate Audra, Selfish Audra, etc. I really enjoyed doing that.

Which, of course, probably means that with the next play I write, I’m going to make three different versions of every scene. I’m pretty sure Samuel Beckett did the same thing. Even if he didn’t, I’m going to pretend he did.

.jpg/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

On why there are no 'perfect' decisions in Watch Me Jump

Because there are none. You can go through life trying to be the nicest person and still hurt someone, including yourself. So, with the play, and especially with the game, I was interested in a narrative that emphasized personal priority rather than the idea of “right vs. wrong”. I was very inspired by games like Papers, Please and The Walking Dead in that regard.

But it’s not easy. I get very attached to the people I write. I was given a note early in my playwriting career that I was too nice to my characters, which kept my stories from having, you know, conflict. So now, I recognize that for the sake of the story, I have to hurt my protagonists and the people they care about. Which I usually do while crying and repeating, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry, I know, this is awful, I’m so sorry.”

Paying homage to the narratives of his youth

The first reason was my initial lack of resources. Typically, when I’m charting new territory, I tend to do it alone, mainly so that I only have myself to blame if it crashes and burns. So, if I was going to create the artwork, I realized the most effective method would be to teach myself to replicate the narrative games I grew up with.

Which leads to the second reason. I grew up in the era of Monkey Island, Full Throttle, and Day of the Tentacle, and, being a Sega Genesis kid, I was a big fan of Phantasy Star IV. These were all games with compelling narratives and memorable characters, and they had a huge influence on my impressionable young mind. So, I decided to pay homage to the games that helped teach me storytelling by trying to incorporate elements of their visual styles.

The draw of simple controls

Coming from the theatre community, I knew that my friends and family were likely going to be the first people to play the game. In order to help lure non-gamers in, I wanted to make the task of playing Watch Me Jump accessible without being overly simplistic. It was a bit of a learning curve to unlearn what I had taken for granted as a gamer, such as when one of my testers noted that they didn’t know what “WASD” meant.

One of the advantages this had was making it easy to port to mobile, which I hadn’t initially planned on doing. Then again, I also hadn’t initially planned on turning Watch Me Jump into a game. I hadn’t initially planned on being a game developer. None of this was initially planned. I had no initial plans. Anyway, what was the question?

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like