Do Not Feed the Monkeys puts players in charge of multiple camera feeds looking in on the private lives of various people, but asks them not to mess with their lives. Will they resist, though?

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

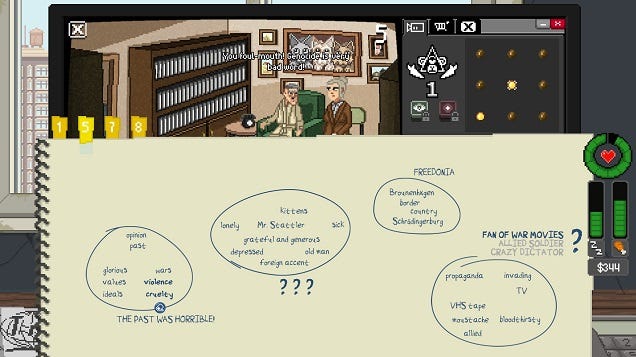

Do Not Feed the Monkeys puts players in charge of multiple camera feeds looking in on the private lives of various people, but asks them not to mess with their lives. With all of this information being unveiled to them, and the mysteries of these lives laid bare, can players resist the urge to interact with them in some way?

The Oliván brothers - developers behind the Seumas McNally Grand Prize, Excellence in Design, and Nuovo Award nominated-game - spoke with Gamasutra about the thoughts that went into creating a game about watching people, the mysteries that can be found in ordinary lives, and how taking a lighthearted look at some unsettling subject matter made it more approachable to players.

High-tech zookeepers

We’re Mario, Alberto, and Luis Oliván: programmer; narrative and game designer; and producer of Do Not Feed the Monkeys.

We started making games…let’s say professionally, in late 2013. Before that, Mario had done some small games in his free time, but none of us had been in touch with the video games industry, other than as players.

We, the founders of Fictiorama, are three brothers that have been playing video games since video games entered homes! In fact, our first computer was a ZX Spectrum 48K.

We played together for ages, mostly narrative-driven games, which we love. In fact, the idea of making our own video games as a team started back then, when we were kids and teenagers. Back in 2013, we decided that we wanted to create together the games we’d love to play, and that’s how Fictiorama was born!

Since then, we have developed two commercial games: Dead Synchronicity: Tomorrow Comes Today (2015), an old-school point and click adventure game released on PC, iOS, Android, PlayStation 4 and Nintendo Switch. And, well, Do Not Feed the Monkeys (2018), which is our most ambitious game so far!

A game of watching other people

In the beginning, Do Not Feed the Monkeys was inspired by the main character of a novel we read a few years ago, who, now and then, stares at his neighbor, who lives in front of him, and watches him dancing, all alone. This guy, the “watcher”, can't stop wondering about the reasons for that: is his neighbor taking classes and he likes to practice, but he doesn't have a couple? Does he try to recall happier times, when he used to go dancing with the person he loved?

We thought it would be really interesting to develop a game with main mechanics that involved watching other people and trying to find out about the reasons behind their behavior - wondering about their lives. Of course, the film Rear Window came to our minds really quickly, but we thought an interface like the main view of the movie had certain restraints regarding the number of people to spy on, and the kind of stories we could tell. So, we kept looking for inspiration about the final approach of the core idea behind the game.

Spy gadgets

We used Unity 3D as the main engine, and then an in-house, custom narrative design tool to create and implement the storylines, dialogues and so forth into Unity.

We tracked progress and managed the production using HacknPlan, a great tool made by some Spanish mates, that we definitely recommend to every video games producer.

Unsecured camera inspirations

After watching movies like Rear Window and The Life of Others, and re-playing games like the good-old Little Computer People, looking for the right approach for our new game, we happened upon (and grew really terrified about) the existence of websites like www.insecam.org. These sites feature the video feeds from thousands of unprotected surveillance cameras worldwide, placed out in the open in highways and streets and nature backgrounds, but also in malls, restaurants, libraries, bars, warehouses... and even private homes! Then, we decided to mix the two ideas: what about a game in which the avatar had access to dozens of live camera feeds so that they can spy on people, and try to guess about the lives of the watched people?

We loved with the idea immediately. It allowed us to tell lots of stories featuring different genres, and to experiment with complex, rich narrative and game mechanics in a very creative way. So, we started working on the game as it is now in January 2016, hand in hand with our mates at Badland, and finished the game almost three years later, published by Alawar Premium.

A means to tell many different stories

After making Dead Synchronicity, in which we told a post-apocalyptic, dark, harsh story, we really felt like doing something different and facing a challenge in our next game. We wanted to try different genres and other emotional moods than the ones featured in our first game. Going for Do Not Feed the Monkeys gave us the chance to unleash our creativity in regards to storytelling: in the game there are dramatic, comical, satirical, tragic, terror, sci-fi stories… and more!

We used this diversity to awaken the players’ interest and to engage them, since our goal was to surprise them throughout the game about what happens in the so-called “cages” (the hacked surveillance cameras).

In that regard, we used to layers of “adhesive” to keep players “glued” to the chair and play longer. Firstly, their wish to unveil the mystery of each story: which is the motivation for the people you're spying on (aka “monkeys”)? What do they want to achieve? What are their lives like? And, secondly, their expectations about what they will find in the new “cage” they just bought.

On turning lives (and stories) into puzzles

The balancing of the puzzles was indeed a very important element we had to manage throughout development. In fact, in Do Not Feed the Monkeys, the narrative and the game mechanics are so intertwined that we had to re-write several stories and their puzzles every time there was a rather deep change or adjustment in the game mechanics.

Anyway, we think that, all in all, the success or failure of a puzzle is not so dependent on its difficulty, as it is on developers creating enough motivation so that players focus on solving it, spending as much time as is needed. Without that motivation, we think the puzzle, no matter how easy or difficult it might be, turns into a mere formality - some kind of nuisance.

With that in mind, it’s essential that the puzzles are integrated as much as possible in the story that’s being told, so that the puzzles meld with the plot, the world, and the characters in the game. This was our main guideline when designing the puzzles, so that if we got to create that integration (and, of course, to match the game as a whole), then the puzzle would be part of the stories themselves and not some abstract hurdle.

Our goal was that the empathy that players would feel towards the characters and their stories was what motivated players to solve the puzzles. Therefore, it would diminish the risk that they got frustrated… and the rewards, once the puzzles were solved, would be more pleasant and satisfactory.

Challenging players to manage their time and attention

Deciding what to do with your time and your attention is a very important part of Do Not Feed the Monkeys. So, we wanted to mimic the sometimes unbearable information-overloaded multi-technology-tasking situation almost everyone faces nowadays. You know: you try to be focused and work, and then an email notification pops-up and it’s almost impossible not to pay attention. Then, while you’re starting to read the email (just in case it’s important), a Telegram/WhatsApp/chat notification claims your attention. And then a Facebook sound or a Twitter/Instagram/whatever warning, and maybe the cellphone rings… all that, including the chance to procrastinate a little bit by accessing an on-line store, a digital newspaper, etc.

All of that is definitely changing the way we perceive the world around us and the way we interact with it, and we wanted players to think about it by creating such a scenario in the game.

In fact, the game challenges players by offering all those tools, plus a big amount of cameras to watch, in which the unexpected can happen at any given time. In the early stages of development, we made some prototypes with a grid of 10x10 video feeds, so there were 100 “cages” running at the same time! It would have been too much, not only for players but for us; as developers, obviously we couldn’t make such a huge game.

Besides, in the game there’s an extra distracting element which is people, all of them quite distinctive and peculiar, knocking on the door. So, it’s even up to the players to open the door or not!

The appeal of messing with the people you watch

The “do not feed the monkeys” thing came very early in the development. The Club that gives the avatar access to this hacked surveillance cameras tells you NOT to interact with the people you’re watching… so to not feed the “monkeys”.

Making a game about watching other people seemed cool… but making a game in which you can interact with the people you watch, although you’re told not to because it’s forbidden, seemed even funnier!

Why give the player the ability to interact with the "monkeys"

The game gives players the freedom to act as they want: they can stick to the main rule so that they don’t interact with the watched people, and they will experience a specific kind of game…or they can break the rules and interact with the “monkeys” in lots of different ways. They can do good, they can do evil (well, they can do what THEY think it’s good or evil), and lots of different things can happen.

Our goal with it was to put into a responsibility onto players - one about affecting people’s lives that they accepted voluntarily. We mean: players can finish the game without interacting with any “monkey”, and that’s fine. But if players decide to break the rule, then they will have to commit.

We also tried to build a decision-making system that was not simplistic: sometimes players can make a decision in goodwill, and the outcome might not be what they expected, as well as the contrary.

Besides, different behaviors will bring not only a moral satisfaction or dissatisfaction, but will also trigger outcomes that can affect the resources the players have, and even the game itself, which adds a strategic approach to the way players behave about helping/hurting other people.

On using a (seemingly) lighthearted tone for dark subject matter

When we came up with the final approach of Do Not Feed the Monkeys, we, of course, had to define the mood of the game, the art style, etc. Firstly, we knew the game was going to deal with a main subject that might be quite creepy (the typical “voyeuristic” subjects are quite creepy, indeed). Secondly, the world we wanted to depict was some kind of a political, financial, economical, labor-related, technological, social, cultural dystopia… that, to be honest, seemed further away three years ago, when we started working on the game, than it seems nowadays!

Thirdly, like we mentioned, we wanted to feature all kinds of stories in the game, including some dramatic ones, but also comedy, sci-fi, thriller, horror…

So, we thought that topping it all with a dark, creepy, serious mood could be far too much for players… and for ourselves, who already had our share of darkness with Dead Synchronicity!

We thought that the things we wanted to talk about were going to get to the players in a much more effective way if we “disguised” the messages behind the comical, sometimes absurd mood the game features on the surface, including the retro pixel-art style that makes the game feel misleadingly “light” at first sight.

This mood also allowed us to place the narrative and the game design “layers” of the game in the order we wanted to: the first goal was to make an enjoyable game, and there you have this fun art-style, lots of stories, plenty of options, replayability, engaging mechanics, resource management… On top of this “joy” layer, if players want to go deeper, then they might find more content which might not be just “enjoyable”.

On why they explore surveillance with Do Not Feed the Monkeys

That really worries us, and it’s something we’d like players to think about while they enjoy the game. We’re being watched almost constantly by CCTVs and security cameras (except at home, maybe?), and we really can’t tell who’s behind them or where those video feeds go. Really, you only have to access one of these cam-sites like Insecam and you’ll see hundreds of people that don’t know they’re being watched!

Actually, it’s not only video feeds, but also the huge amount of information about us that’s available online and that, most of the time, we’re willing to share, not only on social networks, but also every time we sign up to a service. A really accurate profile of ourselves might be done with all that information! It’s not that we’re information or surveillance paranoids, but we truly worry about the consequences it might have.

Besides, we’d also like players to stop and think about the world we seem to be heading towards. The world of Do Not Feed the Monkeys might seem a bit distorted, but you could find some of the news depicted in the game as real headlines in real newspapers today!

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like