Nuovo Award-nominated Tales From Off-Peak City Vol. 1 takes players to a hazy New York street corner on a Sunday morning, where a pizza delivery my turn into a high-stakes saxophone theft.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

Nuovo Award-nominated Tales From Off-Peak City Vol.1 takes players to a hazy New York street corner on a Sunday morning, where a pizza delivery my turn into a high-stakes saxophone theft.

Gamasutra had a chat with developer Cosmo D to talk about how their life in music has affected their approach to game design, the art of weaving music throughout every aspect of their work, and how song and sound can be used to inspire curiosity in the player.

Musician to game maker

I’m Greg Heffernan, aka Cosmo D. I made Tales From Off-Peak City Vol. 1 as a solo developer, although 2/3rds of the way in I asked Julian Cordero to help me with the game’s camera system, as he did a similar mechanic in his IGF-nominated game Levedad. I also had my neighbor Jerome Ellis drop by to play saxophone on the soundtrack, and my wife Shannon consulted with me on the game’s narrative.

I’ve been making games for about six years. Before that, I was a full-time music composer and performer, and I had a steady gig making music for TV commercials. One day in late 2013, I started messing around in Unity, as I was a life-long gamer and I wanted to explore creating interactive digital experiences. As time went on, I slowly taught myself development techniques, including how to use Blender, programming, adventure game design, and dialog writing to support what I wanted to express creatively.

While I studied and practiced independently, I was also going to game jams, board game meetups, design talks, one-off courses, and other events in New York City which offered game design creation ideas and advice. My own work was rudimentary at first, but slowly and steadily, my familiarity with the tools grew and I released a series of games of increasing scope.

My first design, Saturn-V, was my initial attempt to turn an original song into an explorable 3d space. My next game, Off-Peak, was more elaborate in its storytelling, level design and music implementation, and wove in my observations about the music industry in New York, all through exploring an art-filled train station. My next game, The Norwood Suite, was more elaborate yet, exploring an old hotel with a musical past, along with the people who inhabited it. The momentum and lessons learned from making those games went into making Tales From Off-Peak City Vol. 1.

An ode to New York & pizza

The concept for Tales from Off-Peak City Vol. 1 came from several angles. First off, it’s inspired by New York, the city I’ve called home since I was eighteen. This game is an ode to the place and the head-space it puts me in when I walk or bike down streets both familiar and new.

Secondly, the game references pizza quite a bit, and every neighborhood here has a pizza spot or five, of varying levels of quality. This game is my nod to the collective obsession with pizza in New York, and how it can be many things to many people - cheap, cultural, decadent, emotionally nourishing, a blank canvas, an obsession.

Tools & a cello

Unity, Blender, Substance Painter, Mixamo Fuse, FaceGen 3D, Affinity Photo + Designer, Ableton Live, Ableton Push, a microphone, some graph paper for maps, and my cello were the development tools I used to build my game.

On the dream-like sense of freedom of Tales From Off-Peak City Vol. 1

On the dream-like sense of freedom of Tales From Off-Peak City Vol. 1

I create this feeling, I think, because of how I frame the games - they all have a ‘cold-open,’ dropping you into the world as soon as it loads, they’re all in first-person, they have no hard cuts, no mid-game loading screens, and you’re not playing as someone else - you’re playing as yourself. Gameplay goals are there, but there’s no timer or imminent threat, so you can take in the space on your own terms, at your own pace. With the camera system in place, you can take in the world even more meditatively, capturing the space I’ve created from angles unique to how you move through the space.

I try to create a space that comes off as mysterious but inviting. Uncompromising, vaguely threatening, yet also welcoming and occasionally humorous.

Music interwoven with all things

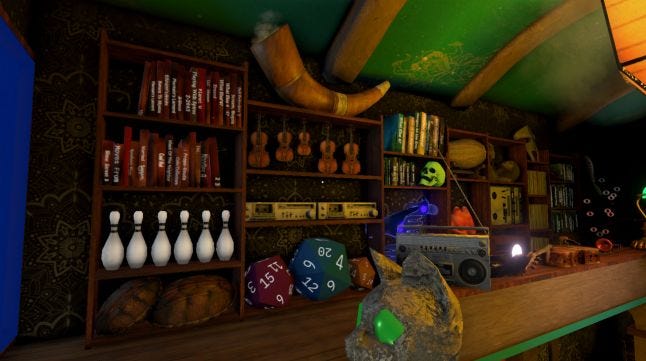

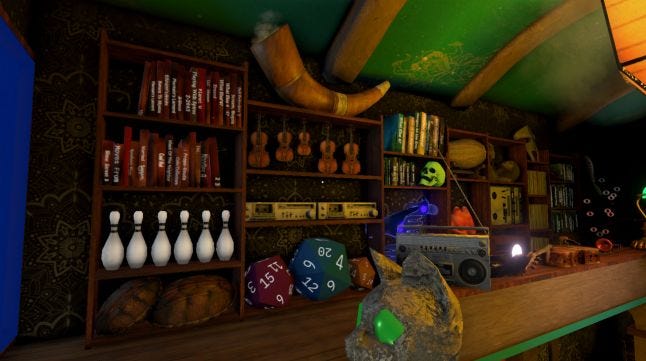

Like in my past games, the music and sound design here is a constant companion for the player. Every room, every character, important or incidental, has some sort of musical accompaniment. It’s diegetically played on boomboxes and sound systems throughout the land, and it plays the role of characters’ back-stories and destinies. It’s also an essential part of the pizza-making process, as players will discover.

Furthermore, the music can be tonally, structurally, and rhythmically ambiguous. Anchors of steady grooves and melody can be offset by a lack of tonal center, no clear downbeat, or no cadence or resolution as chord progressions cycle back on themselves. Melodic themes and motifs come and go. It’s meant to leave the impression that the soundtrack is searching, questioning and unresolved, which echoes the intended player experience.

Developing like a musician

I’ve come to realize that my working style and creative instincts from my music practice have carried over into making games. In the music world, I had to perform only a few takes or compose under tight deadlines, so it got me in the habit of pacing myself a certain way, committing to ideas early and getting them out by any means necessary. Even under these constraints, the work had to meet a certain threshold of quality.

Additionally, I admire musicians who find their ‘voice’ and go deep with exploring it, seeing where it will take them. I once went to a jazz show and the band, who had been playing for several decades at that point, played their first notes of the night and you could instantly tell it was just instant sonic gold pouring out of them. We were witnessing this wonderful amalgam of a continuous musical conversation that had started decades ago. That’s what I aspire to do with my game design practice. I’ve made three games that are an evolution and iteration on a creative vein I hit on six or so years ago, and I want to keep seeing where it’ll take everyone who’s up for the journey.

On having all of their games in a single world

On having all of their games in a single world

This world started zoomed-in and I’ve been slowly panning out to reveal the bigger picture with each game. The opportunity to connect all my games to a single world felt organic - I wanted recurring characters, themes, overlapping stories, and since my games are relatively short and this particular game is ‘Volume 1’, it leaves room for characters to reappear and reassert themselves in different ways across my work. Also, foundational world-building is practical from a development standpoint: once you’ve got a solid foundation for your fiction, you don’t have to spend time building a new world from scratch with every game.

Creating curiosity through pizza deliveries

The game is set up so that the player is introduced to the world and given a job to deliver pizzas around the neighborhood. The impetus is straightforward, and serves to guide players in and out of buildings, where they learn about the world, its characters. Hopefully they go off the main path, discovering hidden stories alongside the main one.

In order to encourage players to explore this game through to the end, I seek a specific balance between heightened sensory experience and gameplay legibility. Very little is mentioned in the UI directing the player. I stage the world in such a way that I want it all to compel players to dive into the world as its presented to them, through landmarks, lighting, and shortcuts. Getting this balance is tricky, and often I’ve had to dial up obviousness over subtlety to arrive at the balance I’m after. It all requires slow iteration, tons of playtest feedback, and an openness to influences across a wide array of art mediums.

Hints & implications

I think a lot of this comes from showing rather than telling - hinting rather than revealing. I don’t have the resources to make the city any more visually intricate, so a lot of the heavy lifting is done through dialog, music and sound design. That said, the economy of the production can, when it’s coming together, heighten the mystery and leave a lot to the player’s imagination.

With dialog, I try to make sure the opening lines get across characters’ personalities, motivations, and relationships. I keep going back to the Downton Abbey pilot - in the span of an hour, they introduce twenty-odd characters, three lines each, and you’re completely inside that universe.

In terms of sound design, I like to place my sounds behind closed doors or walls. The sounds I create tend to juxtapose two dissimilar sources, and when players hear those sounds, their imagination considers what they could possibly be. A fax machine and meditation bowls combine behind the door of Apartment #3… I wonder who lives there?

‘Evidence’ of a scene implied is another technique I use quite a lot. In one scene early on, one of my characters is holding an oversized basketball. Further up the street, two large hoops face each other and traffic cones seem to hint at some sort of street game. While you don’t see the game itself, players can spot all the evidence and let the game play out in their minds.

When all is said and done, the world is consistent with its own internal logic and conveyed in a matter-of-fact way, comfortable with itself. There’s a lot of absurd street drama that unfolds every day in real-life, too. As long as no one’s in danger, people in this city tend to just roll with it. That’s an experience I hope players get to feel, too, in Tales From Off-Peak City Vol. 1.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like