The story behind Cel Damage is long, winding, and harrowing, but ultimately uplifting. And because Cel Damage is our first published title, its story is also the story of a company, Pseudo Interactive. Over PI's first two years, they started up and killed a few projects. However, with the coming of Xbox, we found a proper niche for our emerging technology.

The story behind Cel Damage is long, winding, and harrowing, but ultimately uplifting. And because Cel Damage is our first published title, its story is also the story of our company, Pseudo Interactive. Based in Toronto, we began work on the technological core of the game four years ago. A demo of our driving-combat physics engine at the Game Developers Conference in 1997, PI's first year of operations, received a warm reception. Shortly thereafter, PI struck up a relationship with Microsoft's Entertainment Business Unit (EBU). Over PI's first two years, we started up and killed a few projects. However, with the coming of Xbox, we found a proper niche for our emerging technology.

The story behind Cel Damage is long, winding, and harrowing, but ultimately uplifting. And because Cel Damage is our first published title, its story is also the story of our company, Pseudo Interactive. Based in Toronto, we began work on the technological core of the game four years ago. A demo of our driving-combat physics engine at the Game Developers Conference in 1997, PI's first year of operations, received a warm reception. Shortly thereafter, PI struck up a relationship with Microsoft's Entertainment Business Unit (EBU). Over PI's first two years, we started up and killed a few projects. However, with the coming of Xbox, we found a proper niche for our emerging technology.

The physics engine that PI president and technology director David Wu was developing lent itself well to console applications. EBU recognized this, and an early alliance was formed between PI and the embryonic Xbox team. A high-profile Microsoft producer came to PI with a vision of where PI needed to take its game technology, and a new project was born. At that time, the project was called Cartoon Mayhem and was primarily a car-based racing game with ancillary gag and weapon features. As we struggled with the demands of Microsoft's vision for IP development, rendering, and weapon effects, we realized that the game engine, which was a patchwork of two years' worth of diverging demands and evolution, would need a complete overhaul.

For better or for worse, we undertook that overhaul. So it was that just as we were getting into Cartoon Mayhem's development, our engine, and our ability to iterate content in playable builds, went down for over eight months. This was a crucial time for Xbox and its first-party developers. Microsoft was allocating its resources to those teams with proven track records and those showing steady progress. We were obviously lacking in both areas. Microsoft cut PI, along with our Xbox title, at the end of 2000. Though this was a disheartening development for us, by this time we had the game engine back up and running, and we were suddenly able to produce good demo levels. It wasn't long before we drew interest from several other publishers.

We had a quickly evolving technology and a ton of assets ready to go. The demos we put together enabled us to land a new publishing deal with Electronic Arts. Switching publishers allowed us to prepare some great new material, including an internally developed IP, extra gameplay features, a new renderer, and a new title: Cel Damage. We realized we were going to make the Xbox launch, and we were going to do it with our own property and the backing of the world's largest third-party publisher. These three facts alone made all the work of the previous several years worthwhile.

What Went Right

1. Staffing. Two years ago, when we started work on our Xbox title, we had a core group of about eight people. It was apparent that if we wanted to develop a console game, whole cloth, in time for the Xbox launch, we would need more staff in every department. We hired more team members as we progressed through development. We were fortunate in that we were able to find very talented and motivated people who were also able to contribute to our corporate élan. We brought our staff in from all over North America, and although none of us had console development experience, each new member brought a rich skill set to the company. The search and interview process for each team member was exhaustive. We would often see a candidate two or three times before rejecting him or her and moving on to someone else. Talent and experience were sought-after attributes, but not at the expense of team chemistry. In the end, our hiring methods were vindicated. We were able to create a group of friends who enjoyed working with one another and were deeply devoted to the project.

|

|

| ||

| ||||

| A before and after shot showing cel-shaded smooth groups on Violet's APC. |

Our approach to team communication went hand in hand with our approach to staffing. We found that weekly full-staff meetings, individual weekly lectures or presentations to the entire staff, and regular departmental reviews greatly improved all team members' understanding of how their co-workers contributed to the project.

We also held an ace up our sleeve. We formed a strategic alliance with a local technical college that offered a diploma course in 3D visual arts. Through the school, we instituted an internship program in our art department. We integrated top students into our team, which was a very successful exercise that we will maintain during our next project.

Moral: Wait for the cream to rise, then scoop it off the top.

2. Early development with Xbox. As a new entrant in the highly competitive console market, the Xbox group was looking for game experiences that would make their console stand out. As Microsoft pointed out so often during the Xbox design period, "Great technology does not sell game systems, great games sell game systems." Picking up on that mantra, we started our development when the console was little more than an optimistic dream championed by a charismatic team of visionaries. Chief among them was their bold Advanced Technology Group manager, Seamus Blackley. We were converts to his ambitious plans for the Xbox. With the promise of a stable, RAM-packed, hard-drive-enabled computational powerhouse, we were confident that we could deliver the breakthrough game experience that Microsoft was seeking.

Our game grew and achieved its focus as the Xbox did the same. Knowing that Cel Damage would be held to standards set by second-generation Playstation 2 titles during the 2001 Christmas buying season, we were spurred on to utilize whatever technology the Xbox team was stuffing into the system. We believe that through this evolving relationship, we've managed to create an innovative and highly entertaining title. It's also worth noting that Cel Damage probably would not exist today were it not for the support and inspiration provided by Seamus and the rest of the Xbox team. They stood up for our project and pushed as hard as any of us to make Cel Damage a reality.

Moral: It's all about whom you know.

3. Synchronization tools. PI grew a great deal over the course of the project, and we knew it was important to keep everyone synchronized. The increasing size of the team, combined with the growing mountain of content and code, made regular updates more difficult and time consuming. The process of creating a build became a black art that only one or two people could do correctly.

The first step toward synchronization came fairly early on with the creation of an automated code-compilation process, dubbed AutoBuild. We investigated a few different automated build programs, but none was as flexible or complete as a home-brewed batch file (or rather, a collection of batch files and supplementary programs). Each night, or whenever necessary, AutoBuild could check out all source code to a clean directory tree. It then built and executed any code generators, built all binaries, copied the output to a shared directory, and generated an e-mail report containing a .ZIP file of all build output, along with a summary of errors and warnings. Whenever convenient, our programmers could run another batch file to synchronize completely.

Although we implemented AutoBuild with low-tech Windows commands and utilities, this one-button solution proved to be extremely valuable. Each build that the process generated served as the absolute point of reference for the current code base. Even with six people working simultaneously on the same source code, we were able to keep inconsistencies and problems to a minimum.

|

|

| |

| |||

| A before and after shot using the desert theme's General Store. Cel-shading conventions were prototyped in 3DS Max using the Illustrate! plug-in. |

Another low-tech solution, MakeBuild, filled our largest gap in synchronization, though its implementation came quite late in the project. MakeBuild consisted of our source game content, automatically compiled into run-time format by adding a few simple commands to the game editor, and a few batch files. By automatically running MakeBuild after AutoBuild, we had a brand-new build waiting for us each morning. Our daily build process kept artists and QA staff up to date without bogging down any individual with responsibility for creating the builds. MakeBuild accelerated the feedback cycle between content creation and gameplay review.

Of course, not all updates were visible in the build, and we made several other utilities to help keep everyone abreast of changes under the hood. Our CheckInReporter was a simple Visual Basic program that scanned the SourceSafe database for all check-ins over the previous 24 hours, and then created and e-mailed out an Excel spreadsheet report. These were especially helpful in tracking down regressions. We created another simple VB program that e-mailed out active bug lists to each team member once per day.

Moral: Spending a few days creating simple tools pays big dividends throughout the project.

4. Internal bug tracking and QA. We made sure that our daily build process was up and running before we built our internal QA department. The daily build mentality was instrumental in the iterative process and was QA's greatest ally. New art and game logic assets could be evaluated in-game within 24 hours of their creation, allowing broken assets and bad functionality to be identified immediately.

Asset pound-downs and targeted focus testing ran concurrently as soon as we had four functional game levels. As development progressed, focus testing generated reams of data, which was boiled down to nearly 400 gameplay and asset recommendations. This information provided an important perspective on what people were interpreting as fun and fair. This feedback was very valuable, since we'd lost all objectivity toward the game and its difficulty level once we'd mastered the various weapons and gags.

The bug-tracking software that our internal QA used for the duration of the project was called PI_Raid. This tool, designed and customized in-house, allowed us to stay on top of game defects, generate work items, and comment on evolving game features. We kept our bugs small and focused. While this approach often left each of us with a lot of bugs in our "bin," we were able to close out several per day, providing mini morale boosts throughout the project. Though some of the bugs that we logged might have been considered trivial, cumulatively tackling them had a dramatic, positive effect on the game and our level of polish.

Moral: Get fresh eyeballs on your game and efficiently iterate gameplay.

5. Coordinated schedule. One of the pleasures of working on Cel Damage was the lack of a brutal crunch period in the final weeks of development. We also felt throughout the last year of the project that we'd be able to realize our desired feature set. A good schedule, coordinated with each department, helped us achieve this unique state. Our early work with Microsoft taught us the value of adhering to a schedule, and after we moved on from that relationship, we were able to maintain, and even improve, our scheduling skills. Our guess is that badly maintained and poorly enforced schedules are the primary cause of game projects missing their ship dates, dropping features, and winding up with morale-busting, project-end crunch periods. Following are some schedule-related factors that worked for us: Estimating task duration. No one can estimate with 100 percent accuracy. However, our leads and staff communicated constantly to refine delivery date estimates. If an asset looked as though it was going to run overtime, we would cut it or some of that person's later deliverables, from the schedule. If such changes created holes in the game's design, we would be flexible and design around the holes.

Estimating task duration. No one can estimate with 100 percent accuracy. However, our leads and staff communicated constantly to refine delivery date estimates. If an asset looked as though it was going to run overtime, we would cut it or some of that person's later deliverables, from the schedule. If such changes created holes in the game's design, we would be flexible and design around the holes.

Software. We used Microsoft Project. If you've used it, you know it's not great, but it gets the job done. That was all we needed. Once we got used to Project's idiosyncrasies, it was smooth sailing to the end of development.

Team-wide involvement. We periodically printed the master schedule and posted it on a wall where everyone could see it. This helped in many ways. First, it demonstrated the interdependence of the departments. Each staff member could see that an asset he or she was working on was needed by someone in another department. Second, missing items could be identified more easily, since more eyes were looking at the schedule. Third, seeing the schedule updated gave people a strong sense of making progress. This progress contributed to team confidence and morale.

Short, staggered crunches. We crunched, but we did it early in small, manageable, prescribed intervals, giving us a buffer at the end of the project, after our feature set was complete. People were then freed up to work on visual weapon enhancements and level polish. At the end of the project, the team was playing full- and split-screen Cel Damage during and after business hours. This intense play period helped identify exploits and balance the gameplay. This data wouldn't have been available to us if we had crunched long and hard at the end of the project.

Moral: The schedule is your friend. Never let friends down.

What Went Wrong

1. Design on the fly. Once we got our technology back online in December 2000, it began evolving very quickly. Feature sets for weapon and death effects, driving behaviors, gag functionality, and animations were growing every day. Because we were designing a game to the technology (rather than the other way around), we were throwing out design documents as quickly as they could be written. Art assets had to be revised, retextured, discarded, and rebuilt from scratch several times. As most readers will know from experience, this is a scenario for feature creep, obsolete tool sets, and blown deadlines.

While we were able to nail down our feature set four months before shipping, our evolving engine did cause other problems. Essentially, our strategic preplanning was stillborn. Every week, we had to revise our perceptions of what the game would really be, which frustrated our attempts to describe the game to prospective publishers at the beginning of 2001. Different staff members had different ideas of what our game would finally end up looking and playing like. Fortunately, once publishers and press played the game for themselves, the core of Cel Damage's identity as a cartoon-based vehicular combat game became self-evident.

Moral: It's O.K. to design to an evolving technology, but institute hard cut-off dates for code development and features.

|

|

|

| ||

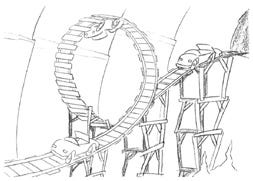

| Early in development, Cel Damage was more race-themed. Here's an early concept for a loop-the-loop road gag in the desert theme. |

2. Asset tracking and implementation. Our initial efforts produced large amounts of art content to show off the Xbox's power. However, evolving performance specs for the Xbox and our game engine, along with a new IP introduced early in 2001, generated several massive content revisions. These revisions were necessary for level geometry, static world objects, gags, skyboxes, cars, characters, weapons - everything. In the worst cases, we saw at least 12 major revisions to individual assets.

While we had an established directory structure for storage at the beginning of the project, new workflows, staff, and management methods precipitated a patchwork of file-naming conventions and tracking methods. Final game meshes were inadvertently overwritten with geometric primitives. We "lost" assets on the server for days at a time. Other tracking problems cropped up as well. A bug in our game engine created duplicate textures that were difficult to hunt down and eliminate. Also, we had a problem with texture revisions that got wiped out on import to the game editor. To compound our headaches, objects were often used in several different levels, but if an optimization was made to one, that change was not automatically propagated through all levels.

Obviously, we needed a tool to track our art assets and their properties and to update content in the game. We created the robust PI_Asset for just such a use. Unfortunately, it was introduced too late in the project for full implementation. As a stop-gap measure, artists began sending out dailies through e-mail. These reports proved useful in tracking what had been accomplished in the course of a day and what should be updated in the build, but data management was still a problem. PI_Raid showed us just how many holes our pipeline had in it. While the primary purpose of PI_Raid was to track and resolve bugs, the artists and level builders found themselves using it as a means to provide a pathway to updated content. Through PI_Raid, a person could know when an asset had been updated, where it could be found, and what had changed in it. Using our bug reporter to track game assets was not an ideal solution, but it did serve us well in a pinch.

While the build-discard-rebuild process hit our staff pretty hard, it created a sturdy springboard for future asset-tracking methods, and it also reinforced a better mentality for thoroughness in our development procedures. Our next project will definitely see better tracking and implementation methods.

Moral: Don't overwrite finished, textured building models with spheres.

3. Single member over-tasking. Due to our relatively small staff, we had to put managers in the critical path of day-to-day asset delivery. These same people held crucial, unique skill sets. As you know, this is a recipe for bottlenecks that hamper development.

One example among several was the role of our art director. We made this person responsible for overseeing the game art, scheduling his staff's workweeks while developing their technical expertise, modeling, creating the game's interface, producing our cutscenes, overseeing interns, and distributing hundreds of art bugs. The time needed for one person to do all these things just wasn't available every day. Fortunately, we were able to create an art lead position to handle the staff and bug tasks. However, not every instance of over-tasking could be fixed by adding a new body.

|

|

|

| ||

| Fowl Mouth and Sinder get down to business in a Cel Damage promotional scene created for EA. |

We had one texture artist, but three or four art staff members were generating meshes. Add to this the frequent discarding of textures and rebuilding of models, and the amount of work crossing the texture desk became enormous. We also had a single staff member who was responsible for updating level content every day. If you consider that on some days we'd generate 100 updated assets, and each one had to be imported, adjusted, and hand-tweaked in the levels, you can gain an appreciation for the bottleneck occurring there. With so many items funneling through one mouse, the balance between efficiency and human error was highly stressed. Ultimately we dealt with the regressions that cropped up, but it's clear that better integration tools for our next project will help a lot.

Moral: Spot bottlenecks early and divert the work as necessary.

4. Last-minute implementation of crucial elements. Our inexperience in console game development caught up with us about three months away from the end of the project. For the better part of two years, we had spent all of our efforts on developing in-game assets and gameplay. As our delivery date to EA came into focus, we realized that we still needed to get a fair bit of content underway, including a solid front-end interface, music, cutscenes, voice acting, foley sound, and sound effects. Once we had our budget in place, we scrambled to pull together a stack of contracted, out-of-house assets.

We drew up a shopping list that looked something like this: 13 cutscene scripts and storyboards, 12 pieces of in-game music, a theme song, interface music, 450 sound effects, 1,000 lines of in-game dialogue and 200 lines of cutscene dialogue to be read by seven different voice actors, six minutes of foley sound and cutscene music, and six man-months of modeling and animation talent. We also realized we needed a way to play back our cutscenes in real time through the game engine and renderer, even through these code elements were not designed to handle the task.

We took on the interface and playback tasks in-house, but farmed out everything else. Obviously, the work was finished on time, but to accomplish this we had to divert the attention of all of our in-house managers to get these items implemented. Spillover bottlenecking was unavoidable. Though we were ironing out implementation bugs until the day we shipped, the quality of the talent and assets we were able to find on short notice shone through in the finished product.

Moral: The last five percent of a game takes 50 percent of the effort.

5. Switching publishers. As we already mentioned, we switched to a new publisher halfway through development. Going from Microsoft to EA was a mixed blessing. While we were able to improve gameplay and develop our own IP, we lost both our financial backing and our internal focus at a crucial time in the project. We were also forced to reinvent all of our art assets to avoid an IP conflict with Microsoft. However, what could have been a project-wide meltdown actually hardened our resolve to get Cel Damage on store shelves. Once we realized that the Cel Damage property would belong to us, and that our mistakes and successes would be our own, the training wheels came off. We became more determined and professional. As a rite of passage, this publishing switch might have been exactly what we needed. In the end, perseverance carried the day, and getting dropped as a first-party title was a black eye from which we recovered.

Moral: When life gives you lemons, start drinking hard lemonade.

Damage Control

Now that Cel Damage is out the door, PI's last monkey is off its back. We are published and moving ahead. There is plenty for us to look forward to now, not the least of which is Cel Damage 2, which we will deliver for next holiday season. We are excited about the prospects for Xbox and hope to continue to exploit its strengths with network and team-based play in our next game. Fortunately, our experiences with Cel Damage have shown us where we can improve our processes and strategic planning on our next venture.

|

Cel Damage Publisher: Electronic Arts |

|

| ||

|

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like