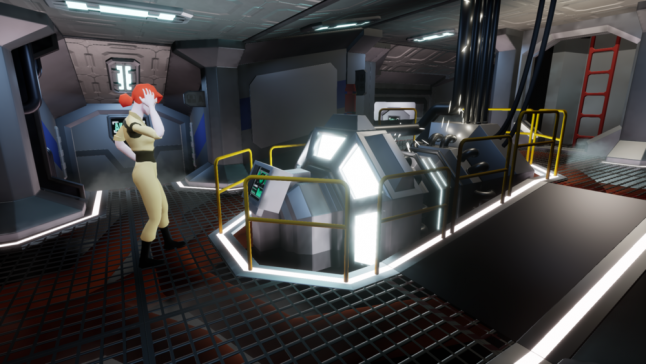

Vessels is a game of ever-shifting identities and pretending to be who you need to be to stay alive, doing anything you can to get out of being dumped into space.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series.

Vessels is a game of ever-shifting identities and pretending to be who you need to be to stay alive, doing anything you can to get out of being dumped into space.

Gamasutra sat down with John Baxa and Caleb Mills of Local Space Survey Corps, LLC, developers of the Best Student Game-nominated Vessels, to discuss the experiences that went into making a game of reshaping the self to stay safe, creating complex feelings in players struggling to survive, and creating characters that would inspire moral conflicts.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Vessels?

John Baxa, Director of Vessels: I'm John Baxa and I was the director, writer, UI artist, and producer on the project. I also put on a pair of glasses, tie my hair up in a loose bun, and bemoan the ‘numbers’ when doing business tasks for the LSSC, LLC.

My background is in psychology, research, & playwriting. I’ve mostly worked on small games, academic projects, and prototypes as I’ve tried to find my place in the indie community.

Caleb Mills, Animator for Vessels: My name's Caleb Mills. I’m the animator, rigger, assistant writer and voice actor for Vessels. Thanks for having us!

My background in games is basically none, same with most of the crew. Alex Pulido, our level designer, worked in QA, but this was diving into the deep-end for all of us. Kind-of a here-goes-nothing leap of faith. That said, we were supported by HOFT institute in Austin, as well as some good mentors.

Quickly want to give a shout out to our other team members & collaborators: Garrett Hale (Programmer), Alex Pulido (Level Design), Travis Carrasquillo (Systems Designer), Nick Morales (3D Artist), Kim Chilton (3D Artist), Rachel Savoie (3D Artist), and Erica Hampson (Sound Designer)!

How did you come up with the concept for Vessels?

Mills: Vessels is John Baxa's baby. He took the concept of isolation, social intrigue, and psychological horror and breathed life into it.

Baxa: I had the initial idea about 7 years ago, but it was more theater than game -- a conversation between someone trapped in an airlock and the person tasked with ejecting them. I just wasn’t ready to make the game then -- it was trope-y, but impersonal. I think what inspired me to reengage with the idea for Vessels was coming into myself more as a gay man and better understanding a key tension of being gay/queer: You spend so much of your life performing a version of yourself to either stay safe, sane, or simply palatable to the people around you. Vessels finally clicked for me when I realized the game could be about that tension: Behaving the way people expect you to in order to survive, but the hollowness/fractured self that comes with that falseness.

What development tools were used to build your game?

Mills: The Unreal engine was our workhorse. A workhorse that bites sometimes. Our programmer, Garrett Hale, built a custom dialogue system to use with Unreal too.

Baxa: It was a Herculean effort on Garrett's part. We always had one member of the team dabbing his forehead with a towel.

What interested you in using death and repetition to unravel a mystery?

Baxa: This was a mechanic Caleb pitched that ended up really making the game better.

Mills: If you had a chance to get do-overs in life, wouldn’t you do it? Undo your mistakes? Give yourself another chance with someone you cared about? I sure as hell would. These are feelings all of us have, and we wanted to draw on those desires. Re-dos are inherently positive, but not if they have a terrible price associated with them. We wanted to change death from a perceived failure to a tool for success and exploration.

What thoughts went into crafting a story that the player could change, bit by bit, with new pieces of information? In creating a story designed to be repeated over and over again?

Mills: Hoo boy. Writing, writing, and rewriting. First, John and I sat down and really dug into who the characters were and what they wanted. Only when we understood the characters in-and-out did we explore the choices those characters could present the player. We had the story, but the characters gave us context.

Baxa: Caleb’s brother was one of our first playtesters and he really wanted to kill Rakesh. We leaned into that strong emotional reaction and built the narrative design along three paths: Revenge, Uncovering the Mystery, and Saving the Crew. We wanted to incentivize possessing different characters to offer a broader range of perspectives on the story, and because certain information would only be accessible by certain characters. One playtester described our game as a “narrative Metroidvania” and that helped us think about how each character and their relationships could propel the player forward.

How did you decide on the various interaction mechanics for the game (possession, interrogation, manipulation)?

Baxa: Because the player is trapped in the airlock for the majority of the game, possession had to be the mechanic to facilitate exploration. Manipulation and interrogation were naturally born out of that. I think the biggest emotional touchpoint that influenced those mechanics was the camp brilliance of ALIAS’ “Francie doesn’t like coffee ice cream” scene (which I referenced in my pitch for the game), as it captures both the fun and horror of realizing that a stranger is wearing the face of someone you trust.

What thoughts went into making room for the player to decide how they make their way through the story (charming people, using them, etc)?

Mills: It’s easy to hurt someone you don’t like. It was essential for John and I to create characters that were either likable or interesting enough for players to not immediately try to go on a killing spree the second they had a chance. RIP to all the Rakeshs we lost in play-testing. Each character has things going on that aren’t immediately apparent. We had to trust that people would be interested in looking a little bit deeper, and using the tools we give them to do so.

Baxa: One playtester told us after she completed the game: “I feel like a sociopath,” which means we were successful. Empathy is the complicating factor in the game. Pretending to be good when you have evil intent delivers that villainous player fantasy really easily. But once you flip it: You’re trying to be evil, but empathy arises as you get to know the characters...it can provoke a far more complicated response in players. Act 3’s drinking sequence with Peyton was the most successful at this flip - players hellbent on revenge and/or neutral to Peyton flipped and realized they didn’t want to hurt her once they heard her story.

The various characters and their secrets form the backbone of the game. What ideas went into creating these compelling, mysterious people?

Baxa: I’m not a big fan of characters who are just available to you as a player. I love subtext. I like it when you learn about a character by how they act and change in different contexts. Here are some key ideas that went into the characters (lots of spoilers!):

Character needs drive, then complicate gameplay: In Act 2, Peyton initially seeks out the player for hellp, but then takes the credit for the player’s work. It’s a smaller character choice, but it does two things: During the mutiny scene, it escalates how the player needs to drive the crew apart to stay alive while revealing more about who Peyton is: Someone who craves respect and is willing to lie a little to get it. It’s an action that can justify a player's desire for revenge against her, but also humanize Peyton further. She’s a touch impulsive and a bit pitiful.

Everyone has versions of themselves: I really enjoy characters who have to balance versions of themselves - often shaped by the contexts they find themselves in. All Esme wants to do is her job, but Rakesh wants her to be an obedient protege. Peyton needs Esme to be her therapist, and Marv wishes Esme could be his girlfriend. Even the lore characters (Esme's mom, the corporate VP Brinley Achard) pull Esme in different directions. Esme obliges all of them until her true self comes out in Act 3. I should say 'one' of her true selves, because they're technically all Esme.

Put something personal into the characters: I draw characters from the people I meet. A few years ago, my airplane was landing when the woman next to me - someone who had been silent the entire flight - started talking. It was not out of the blue, because I could feel this pressure coming from her the entire time. This quiet, intense urge over my shoulder I could feel without looking at her. When she spoke, she told me she was flying home to be with her mother, because her father was a complicated man. He was a marine who liked to drink and he “chose another way out.” She didn’t elaborate on what that meant, but it was clear.

I’m not sure why she wanted to talk to me. Maybe I was a friendly face, maybe she just needed to talk. Maybe, we were two children shaped by our fathers’ mistakes, who happened to select seats next to each other on a plane. That conversation is what shaped the Act 3 drinking sequence and Peyton’s alcoholism. Personally, I’m nothing like Peyton, but she and I have a lot in common.

The last idea, which is more overarching, is the idea of thematic cohesion - that the themes of the game manifest and mirror themselves in different ways across the characters. The player's relationship with the Entity is mirrored in Rakesh's relationship with the company - compliance can remove the individual. Esme balances multiple selves while the player does the same. Peyton mirrors the final choice the player must make - that despite terrible circumstances they can give in to forces seeking to control them or choose the 'self' they want to be.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like