A postmortem of The Wild Within and Scarlet Moon by a student producer at SMU Guildhall

TGP1 Postmortem – The Wild Within and Scarlet Moon

Wild Within Logo

Scarlet Moon

Over the last eight weeks, I served as assistant producer for two student teams participating in their first Team Game Project (TGP1) here at the Guildhall. Each team consisted of five underclassmen and myself, each team creating a demo of an original 2D side scrolling game using GuildEd, a new proprietary 2D engine developed for the program. By the end of the project, each team found great success overall, and the teams learned significant lessons preparing them for the larger projects ahead.

The Wild Within is an action side-scroller with similarities to classic platform games such as Sonic the Hedgehog, Earthworm Jim, and Donkey Kong Country.

Flaming Shark Tornado

Early in design of The Wild Within, Team Flaming Shark Tornado was aware that the technical challenges of an unproven game engine were a significant risk to development. With this in mind, the team decided to implement a game with relatively straightforward mechanics they were certain they could develop in the project schedule and then highly polish the art and gameplay. The main character of The Wild Within, Tiponi, is a young shaman girl who traverses two forest levels of enemies and jumping challenges. Tiponi can run and jump, and can summon the spirit of a bear to aid her in combat and can summon the spirit of an eagle to extend her jump. Animal spirits surround her when she attacks, double-jumps, and glides.

WW Concept art

A checkpoint system, environmental hazards, two types of enemies, point pickups, health pickups, and a health system round out the major mechanics of The Wild Within.

Near the end of production, the team’s early worries about technical challenges with their new engine did become a significant roadblock, starting around the Alpha milestone. Fortunately, with significant effort the team pulled together in the few remaining weeks to release a beautiful game that is intuitive and smooth.

WWScreenshot2

What Went Wrong

The art style wasn’t consistent at the beginning.

On a 2D game with two artists with different art backgrounds, the team had growing pains developing a style and distribution that benefited the team as a whole.

Approval processes sometimes unclear or not followed.

On a team of such small size working in close quarters, it is easy to ask the teammate sitting beside you their thoughts on your work. It is also easy to take these steps for granted, to skip the approval process as tough deadlines approach, or to have hesitation about giving honest criticism.

GuildEd limitations on size meant that art pipeline was detrimental

GuildEd is currently a quirky beast who requires a watchful eye. The original art pipeline planned on the artists putting in rough art content to start, allowing the level designers and programmer to develop gameplay early. The artists could then iteratively improve the art as time allowed. However, GuildEd projects require inconvenient maintenance when developers replace art assets, or else memory allocation becomes a significant problem.

GuildEd challenges were extensive for all disciplines, specifically memory leaks.

Unforeseen memory problems due to the way GuildEd loads assets meant that problems emerged late in development where they did not exist earlier. For the level designers, in some cases this meant that rebuilding a level to a new specification was easier than fixing the assets within a level. For artists, this meant some resizing of art assets. For the programmer, this meant developing workarounds to deal with engine issues with a low degree of visibility.

SVN procedures not well-established

Before each milestone, the team would sometimes burn midnight oil to get the game ready for the upcoming Kleenex test. Unfortunately, this also meant that game updates sometimes happened in large, untested chunks, which made debugging extremely challenging.

Inadequate communication and organization at the end due to bugs

At the end of development, the team partially abandoned some of the organizational structures set in place in the struggle to get the game working again. This put some undue stress on the team as a whole and some worries for the success of the project.

What Went Well

Art style and content very positively received

The Wild Within had a highly talented and motivated art team, and the art content was always a highlight for testers.

SCRUM helped with project visibility

For the vast majority of the project, the team followed SCRUM with rigor, meaning that the team was able to see the bigger picture in terms of project status. Time management and estimations became more accurate and useful as the project progressed.

Peer evaluations were very effective

Team morale and communication problems emerged occasionally during development, and some of the team originally had doubts to the usefulness of the peer evaluations. However, the positive responses to peer feedback were strong and obvious throughout the team, and the atmosphere of the team benefitted as a whole.

Level designers resolved content issues by figuring out a development system, then copied each other’s methodologies

The level designers were able to work in tandem on their levels by resolving different design and technical challenges, sharing their findings, and sharing them with the the other level designer for use on their own level.

Issue manager used and effective

Issue Manager turned out to be one of the team’s best lines of communication. In terms of sharing information, prioritization, and making sure the small stuff doesn’t fall through the cracks, the team found the tool useful early on, and encouraged its use throughout development.

Assets very modular and project highly expandable

By the end of the project, as the major engine roadblocks were uncovered and better understood, the team found itself with a game that has great potential for expansion. Given the opportunity, the project’s structure was developed in a way that mechanics and content could now be added with relative ease compared to the growing pains of the development of the demo.

What We Learned

Early and frequent QA and testing is very important

Don’t take engine capabilities for granted – there may be will be issues you’ll need to adjust to

Sacrifices to content are going to be necessary when the unexpected arises

Time management, procrastination, voluntary overtime, and prioritization of TGP to your other classes are all important factors to consider when looking at the TGP process

Making mechanics fun can be even more important than original or interesting mechanics

Designing based on tech limitations is valuable, when you have the opportunity

Underscope and polish

In small projects, sometimes the best solution is restarting something

SMLogo

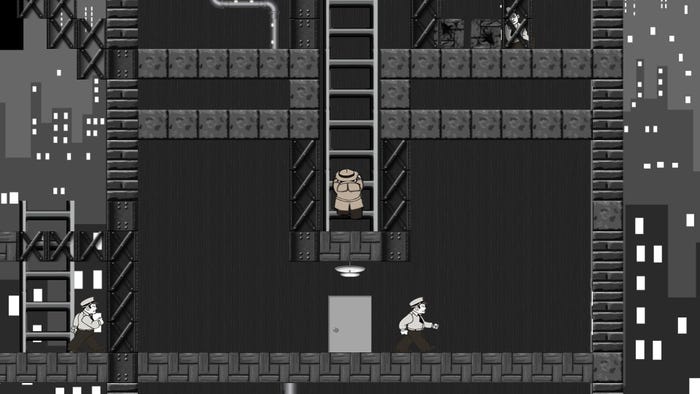

Scarlet Moon is a side-scrolling stealth puzzle game with similarities to Elevator Action, Mark of the Ninja, and Trilby: The Art of Theft.

1-ders

Team 1-ders developed Scarlet Moon starting with a curious theme, powered by enthusiasm.

The design of Scarlet Moon focused began a mystery noir theme set on the moon during the Cold War. Players take control of Private Investigator Maurice Mooney in order to solve the conspiracy around the murder of Miriam Miller. Maurice must use his considerable sleuthing abilities in order to distract, avoid, and trap security forces as he seeks for the clues to find Miriam’s killer. Patrolling security guards sprint toward Mooney when they see him, and security cameras shoot him on sight. Environmental hazards, such as collapsing floors, thwart Maurice’s progress. Maurice uses his cunning to find a way to evade the guards and traverse the environment, including hiding from guards, finding new paths to avoid them, and figuring out how to trap them.

Hiding behind doors, lockpicking, sprinting, fuse box sabotage, a stealth chokehold, crate pushing, and an elevator system cover the major mechanics of Scarlet Moon.

The team’s efficiency and strong work ethic allowed them to add wishlist mechanics late in development and create a game with significant features derived from feedback and iterative polish.

SM Screenshot 2

What Went Wrong

Too reactive to suggestions and criticism by testers

At each Kleenex test, the team took all suggestions and criticism seriously, often making significant design decisions based on Kleenex feedback. In retrospect, team thought that their changes made the game better overall, but they felt they should have been more selective in their reactions.

Not updating documentation regularly during production

Updating outdated documentation late in development was a time sink for multiple team members, and the documentation was not current when the team gained a new level designer midway through the project.

Some procrastination and time management issues; sometimes saves components for later thinking assuming time would be available

While the team was able to implement significant level design and programming content late in development, the art team wished for more time to iterate on art.

Unexpected tech problems such as SVN and computer issues

GuildEd and SVN didn’t always perform reliably, and more than one team member lost valuable development time to technical issues outside their control. On a project with such a tight schedule, even a single day lost is a significant percentage of development time for a team member.

Time went by quicker than expected; difficult to judge time requirements

As first-time team members on a game project, estimating development time for tasks was difficult and often inaccurate.

Didn’t use issue manager to its fullest

While the team appreciated the utility of Issue Manager, they did not always use it when appropriate. The team communicated most bugs verbally. While this proved adequate for a team this small, the team feels future projects will require more strict usage of Issue Manager.

Some miscommunications due to hesitancy for confrontation

The team felt their need for friendship and amity sometimes made them less assertive than was best for the project.

Not following naming conventions

What Went Well

New level designer

Midway through development, Team 1-ders was progressing smoothly and performing slightly ahead of schedule. At this point, a second level designer joined the team, requiring the team to adjust and try to integrate. Fortunately, the new team member brought a valuable new perspective and challenge to gameplay, and his productivity gave the team the opportunity to expand the game’s content.

Programming and debugging went quickly

The team programming progressed with efficiency, frequently allowing team members to communicate multiple bugs and mechanics suggestions and see them addressed almost immediately during the same work period.

Game development ended up very open and flexible.

The team felt they originally scoped small and added significant polish as they determined what pieces of the game were fun and valuable. Small programming tweaks added a lot of depth to the game.

Team functioned well as a whole

The level of project organization was very high, there were no major personality conflicts, and each team member took initiative to help others out. The team experienced a high level of project buy-in from day one.

Team skill level was high and had complimentary skills

The team felt that the sound effects were highly effective, the art style was solid and fun, and the puzzles grew increasingly intriguing, and the game mechanics received significant polish for new gameplay.

What We Learned

Organization and time management very important

Learn how to work and communicate in a cross-discipline team

Learn how to use project management tools correctly

Placeholder assets are very helpful in the long run.

Start small and leave room for polish

Keep core project goals and direction in mind; don’t be too reactive

Don’t procrastinate

In conclusion, development of The Wild Within and Scarlet Moon were challenging, fun, and instructive projects for my teams. During development, I was given the opportunity to watch them when they first realized the need to cut a feature, when they noticed the benefits of the tools and processes they were ‘forced’ to use, and when they finally burned their RTM discs. When development began, I shared some of my own experiences and lessons learned in my first TGP project at the Guildhall (and hope that served some use), but that really doesn’t compare to learning firsthand. I hope to work with them again in the next year here at The Guildhall, and maybe even beyond.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like