Most of the time The Designer's Notebook is full of opinionated jottings about creativity, storytelling, or the social effects of interactive entertainment, however, every now and then Ernest feels compelled to write something abstruse and technical about game design, something that's more of a how-to than a why-to or a why-not-to. This is one of those times.

Most of the time The Designer's Notebook is full of opinionated jottings about creativity, storytelling, or the social effects of interactive entertainment - in other words, blue sky. Every now and then, though, I feel compelled to write something abstruse and technical about game design, something that's more of a how-to than a why-to or a why-not-to. This is one of those times. This month I'm going to talk about the effect that positive feedback has on game balance.

What Is Positive Feedback?

When we speak of feedback in everyday life, we're usually referring to that horrible shriek that happens whenever the microphone in a public-address system gets too close to the speakers. The mic picks up whatever's coming out of the speakers and tries to amplify it again. More generally, feedback occurs whenever the output of any system is "fed back" into it as some kind of an input. What happens with the microphone and the amplifier is an example of positive feedback - a situation that tends to amplify the output of the system.

Positive feedback plays an important role in game design, although you don't hear many designers talking about it. It can gravely harm a game if improperly implemented, but it also has significant benefits. It's an element of game design that every designer needs to understand and learn to use.

Before I go into how it works, though, let's look for a minute at the way games are won and lost. When you happen across two friends playing a game, what's the first thing you say? "Who's winning?" of course. That's not always an easy question to answer. Some games have a metric that determines who's ahead at any given time; others don't. In ping-pong, for example, it's obvious: whoever has the most points is winning. In chess, it's less clear because the victory condition - checkmating the king - is not defined in terms of accumulating points. You can very generally say that whoever has taken the most pieces is winning, but it's perfectly possible to win at chess with fewer pieces than your opponent has.

In game design, positive feedback can be defined as occurring whenever one useful achievement makes subsequent achievements easier. In other words, whenever someone gains something in a game, it gets easier to make further gains. If the role of positive feedback in a game is too great, then whoever first obtains the slightest lead in the game is guaranteed to win, because they just keep getting farther and farther ahead. This makes it sound as if positive feedback is always undesirable, but it isn't; it's just a question of employing it properly.

Positive feedback appears mostly in games in which the victory condition is defined in numeric terms, and throughout the game you're working to achieve that victory condition by accumulating something. In Monopoly, for example, it's money. Obtaining money in Monopoly allows you to buy and improve properties, which makes it possible to obtain more money. Positive feedback can also appear in games in which a numeric advantage of some kind helps to achieve a non-numeric victory condition. Although the victory condition in chess is non-numeric, it does generally help to have more pieces than your opponent.

Balance Graphs

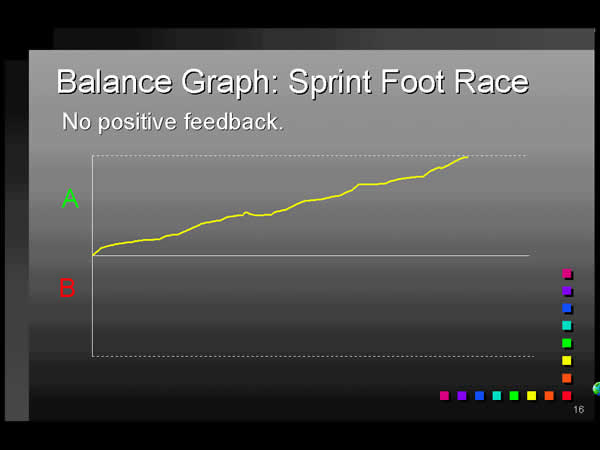

So what are some of the effects of positive feedback on games? I think it will help to look at something I'm calling a balance graph, although there's probably a different name for it in formal game theory. I've included several of them below. A balance graph plots the progress of a zero-sum two-player game. Time is represented on the horizontal axis. The vertical axis indicates who's ahead by some numeric metric, usually the difference in points scored by the two players. If player A is ahead, the number is above zero; if player B is ahead, it's below zero. At the left edge of the graph, the beginning of the game, the players are even at zero. Dotted lines at the top and the bottom of the graph indicate the victory condition for either player A or B.

My first balance graph represents a simple sprint foot race in which player A is a faster runner than player B. A immediately goes ahead and remains ahead for the duration of the race. Straightforward races have no positive feedback. Gaining the lead does not make it easier to retain or increase the lead. (In fact, there's psychological evidence to suggest that the opposite is true: runners try harder if there's someone slightly ahead of them. When Roger Bannister was training to break the four-minute mile, he ran with pacesetters who ran in front of him. This phenomenon has also been observed in racehorses and sled dogs. However, it isn't part of the rules of the game, which is what we're concerned with here.)

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 1 |

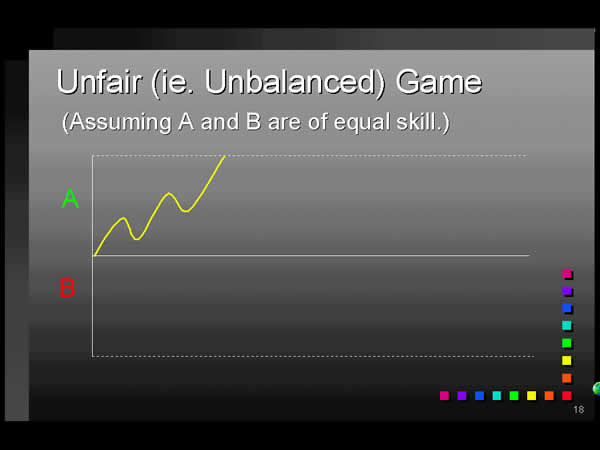

The next graph is an example of an unbalanced, i.e. unfair, game - whether or not it includes positive feedback. Assuming that A and B are of equal skill and there is no element of chance involved, something about the rules is giving A an advantage, such that she takes the lead and maintains it throughout a very short game.

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 2 |

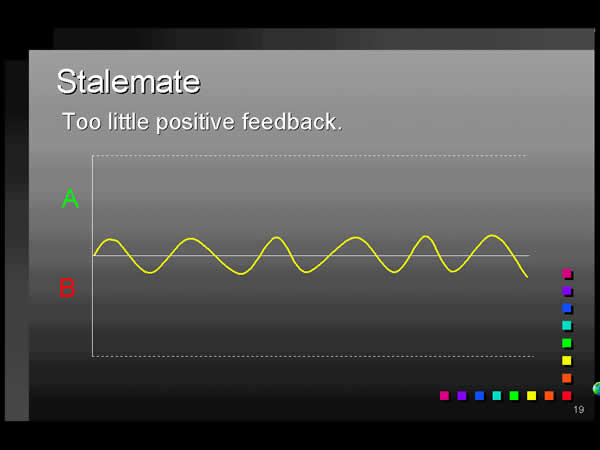

In Figure 3 we have a stalemate, a game that goes on forever with neither player able to assume a commanding lead. This is a game that's too balanced: neither player is able to achieve victory. The children's card game War is a good example of this kind of game: it's all luck, no skill, and no positive feedback, so it can go on for hours. This illustrates why positive feedback is a useful thing: it helps to prevent stalemates. Once a player assumes enough of a lead, the advantage that positive feedback confers guarantees that he will win.

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 3 |

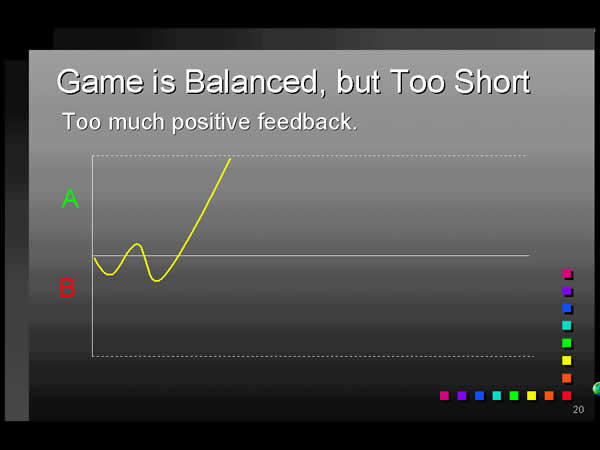

Figure 4 illustrates a game that's balanced, but positive feedback sets in too soon, producing a fair but very short game. B gains a slight advantage, then A retakes a slight lead, then B again, then A takes a longer lead and promptly wins the game.

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 4 |

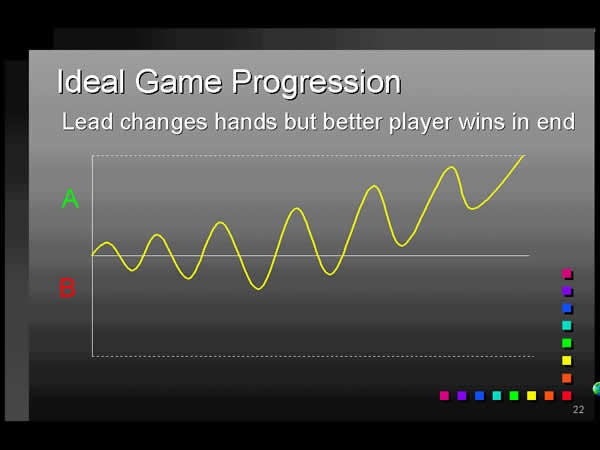

The ideal game, in my opinion, starts off even and balanced, but slowly becomes unbalanced over time until one player inevitably wins - preferably the better player! Figure 5 shows one example, although in this case player B struggles on valiantly for quite a while.

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 5 |

Once a player's lead becomes commanding, the game shouldn't take too long to finish. This is one of the (very few) problems with Monopoly. From the time that it becomes clear that one player must win until he has actually bankrupted all the other players is usually half an hour or more. The other players just have to sit and wait through their slow slide into oblivion.

Positive Feedback in Games

So let's look at some examples of games with and without positive feedback. As I mentioned before, races and most other athletic competitions don't have positive feedback - at least, not designed into the rules. Scoring points in basketball doesn't make it any easier to score further points. Nor do most card games: cribbage or rummy, for example. On the other hand, war games definitely do have positive feedback, especially if the victory condition is simply to wipe out all the other player's units. Destroying an enemy unit confers an advantage to the player who does it. The unit no longer there to fight back, so it's easier to destroy the next unit, and so on.

Another genre of computer game that has positive feedback is single-player role-playing games. You start off with poor weapons; you kill some monsters; you get some treasure, and you use it to buy better weapons. The better weapons enable you to kill more monsters, you get more treasure, you buy still better weapons, and so on.

Positive feedback needn't have a direct influence on the path to victory; it can appear in other areas of a game as well. While I was at Bullfrog Productions, I was lead designer on a new game (never published, alas) called Genesis: The Hand of God. Genesis was a god game in the spirit of Bullfrog's original Populous, in which you could affect the weather of a landscape with divine power, drawing on mana generated by your simulated worshippers to do so. One of our innovations was that there were several different types of mana, depending on the nature of the landscape in which your worshippers lived. For example, if they lived in a wet area, you got a lot of water mana, which you could use to make rain. Of course we realized immediately that this was a positive feedback loop: the more water you had, the more water you could get. On the other hand if your people lived in a desert, it was very difficult to make rain because they were producing very little water mana.

In the end we concluded that this wasn't a problem for the game. Making rain in a wet area made it wetter, but so what? If you made it rain all the time you would drown your own people, and there was no benefit in that. We also thought that making the desert bloom shouldn't be too easy at first, but once you got it started, it should get easier. Although it was positive feedback, it didn't endanger the balance of the game because it didn't confer a direct advantage over your opponents.

Controlling Positive Feedback

So far I've looked at both the benefits and the dangers of positive feedback. The benefit of it is that it prevents stalemates, helping games to come to an end. The danger is that it will unbalance a game too quickly and bring it to an end too soon. So how can we limit positive feedback? There are several ways.

Use Negative Feedback

Negative feedback is the opposite of positive feedback; it's an effect that tends to diminish, rather than amplify, the output of a system. A good example of using negative feedback to control positive feedback is the way that the player draft works in American professional football. In general, a team that wins a lot is going to have more money than a team that loses a lot. A winning team could use that money to outbid other teams to hire the best new players graduating from college. The best teams get more money, which enables them to hire the best players, and so they continue to win. Poor teams can only afford poor players, so they continue to lose - a clear case of positive feedback.

In order to prevent this, and try to balance the strength of all the teams, the National Football League introduced a drafting system. New players can't simply auction themselves to the highest bidder; rather, the teams take turns to choose players from those available, and most importantly, the worst teams choose first. This means that the worst teams get first choice of the best players, and the quality of the teams is evened out somewhat. Of course, it's not that simple in practice; teams are allowed to trade their positions in the selection order, and the quality of their play depends a lot on the quality of the coaching, not to mention the other players already on the team. But the principle is sound. The draft system helps to prevent one team from establishing an unassailable position through positive feedback.

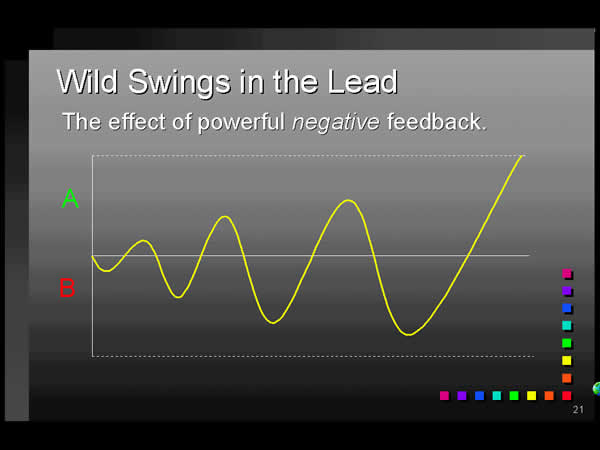

Be careful about negative feedback, however - if it's too strong, it can produce stalemates or even wild swings in the lead, as Figure 6 illustrates. In this example, being in the lead confers some kind of strong disadvantage that causes the lead to flip to the other side and back again.

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 6 |

You often see this in turn-based multi-player party games for adults, in which the object isn't really to reward skill, but to have a good time without worrying too much about who's winning. Everybody gets to be in the lead at some point, and the winner is mostly a matter of chance.

Limit the Benefits that Positive Feedback Provides

In chess, it's obviously helpful to remove your opponent's piece from the board. But imagine what chess would be like if you could not merely remove the piece, but turn it into one of your own. This would confer a much greater benefit to taking an opposing piece, in other words, stronger positive feedback. Chess games would be shorter. This actually happens in Japanese chess, which is called shogi. A player who has removed an opposing piece from the board may reintroduce it at a later point as one of his own (with certain restrictions).

This is why most real-time strategy games don't allow you to seize enemy units and use them yourself, nor do they allow you to take over enemy production facilities. If you could grab your opponent's factories and start turning out units for your side, the game wouldn't last very long. They are limiting the benefits that positive feedback provides.

In addition to the drafting process, pro football has other rules that help to prevent the wealthiest teams from dominating all the others year after year. One rule is the salary cap, which limits the total amount that each team may pay all its players. No matter how much money a team has, it can't spend more on salaries than the salary cap dictates. Another is a fixed team size. No team can have more than 53 players during the regular playing season, even if it can afford to. These artificial restrictions serve to constrain the effects of positive feedback. In effect, they're making sure that "money isn't everything."

Define Victory In Other Terms

As I mentioned earlier, the victory condition doesn't have to be defined in terms directly influenced by positive feedback. In chess, victory is defined in strategic rather than numeric terms. In real-time strategy games, you can create missions in which victory must be achieved by stealth, or by detecting a weakness in the enemy defenses, or by surviving for a certain amount of time, or any number of other scenarios. One of the weaknesses of RTS's at the moment is that too many of them depend on overwhelming the enemy with sheer numbers - in effect, production efficiency - rather than rewarding strategic skill. This leads to a "cannon-fodder" mentality among players that is uncomfortably reminiscent of Field Marshal Haig at the Somme. Let's hope they don't practice using those kinds of games at West Point.

Ratchet Up the Difficulty Level to Compensate

This is exactly what role-playing games do. As I described above, there's clear positive feedback in the character growth: winning battles enables you to buy better weapons which enables you to win still more battles. If you always faced the same kinds of opponents, you would quickly become invincible, and the game wouldn't be much of a challenge. Therefore, as your character's strength and ability grows, the game increases the toughness of your enemies as well. The difficulty of winning each battle remains fairly constant (with local variations) throughout the game.

Increase the Influence of Chance

This isn't the best way to reduce the effect of positive feedback, but it does work. Monopoly does this to some extent. One bad roll of the dice can set the leading player back significantly. Of course, it can hurt just as much as it can help, unless you load the dice against the leading player - and if you do that you'd better not tell them about it! Children's games tend to rely on chance more than games for adults do. It helps to balance out disparities in skill and allows the loser to blame bad luck rather than himself (I don't necessarily endorse this, I merely note it).

Conclusion

Balancing a single-player computer game is a bit different from balancing a multiplayer one. In a single-player game it isn't necessary to be "fair" in quite the same way as it is in a multi-player game. The challenge in single-player real-time strategy and role-playing games usually depends more on the player's ignorance of what he's up against than the computer's strategic or managerial skill - often because the computer doesn't have much. But most RTS's are designed with multiplayer modes these days, and in those cases it is necessary to balance them properly and make sure you're being fair to each player, especially if they have asymmetric forces. In multiplayer mode, positive feedback has an important role to play. Use it wisely!

______________________________________________________

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like