Roaming around an open world RPG like Falllout 4 can get boring when you run out of stuff to kill. Tabletop games like Fall of Magic and Tokaido show how we can make travel meaningful through play.

It’s hard not to wonder if Bethesda was making a clever statement with their choice of Dion’s immortal classic “The Wanderer” as the theme song for Fallout 4. The song, in addition to being toe-tappingly catchy, is one of those palimpsests whose up-tempo music belies a dark theme. In Dion’s own words:

“You know, ‘The Wanderer’ is really a sad song. A lot of guys don't understand that...It's ‘I roam from town to town and go through life without a care, I'm as happy as a clown with my two fists of iron, but I'm going nowhere.’ In the fifties, you didn't get that dark. It sounds like a lot of fun but it's about going nowhere.”

In other words, it’s very appropriate for an open world RPG composed of shallow relationships, aimless wandering hemmed in by invisible borders, and “fists of iron” in the form of whatever weapon you happen to be using to take down your level-appropriate enemies. Reading the song through Dion’s original intentions, you get a sense of the fundamental sadness at the core of many open-world RPGs: for all their freedom, the journey is ultimately an aimless one. Though I strongly prefer this style of RPG design to the “on rails” variety favored elsewhere, the problem of the player being unable to craft a truly meaningful experience persists.

"Roaming an open world RPG like Falllout 4 can get boring when you run out of stuff to kill. Tabletop games like Fall of Magic and Tokaido show how we can make travel meaningful through play."

Part of the problem comes down to a fundamental issue I’ve addressed in this space before: why do we travel? In roleplaying games, what is there beyond blowing up the bad guys in spectacular fashion? When all that’s done, what’s left? The ineluctable fact about open world RPGs is that they get boring right around the time you run out of stuff to purposefully kill.

There are other games that have more nuanced and interesting takes on travel, certainly 80 Days which I can’t praise highly enough, but also some tabletop games that have used their low-tech medium to show how we can make travel meaningful through play.

***

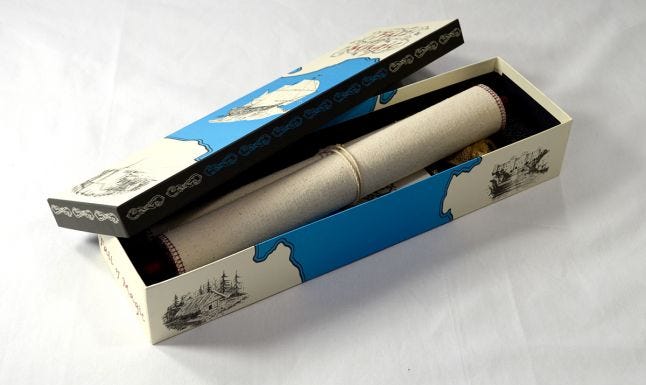

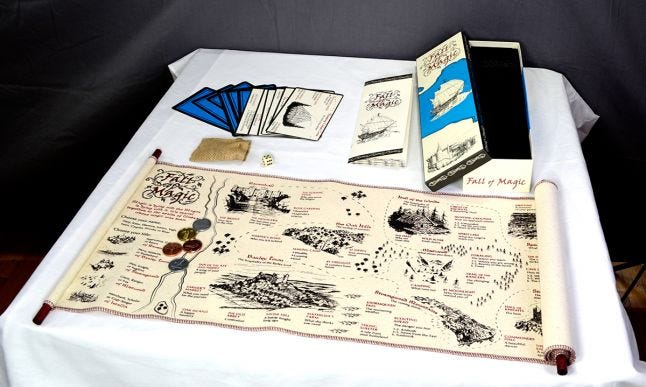

Back in October I had the pleasure of playtesting Heart of the Deernicorn’s latest, and arguably greatest tabletop roleplaying game, Fall of Magic. From the moment you open the elongated box you’re treated to a novel experience: the entire gameworld literally unfurls before you on a cloth scroll. The visual hook draws you into designer Ross Cowman’s magnificently designed world, which manages a tricky balance of being detailed enough to be original, but broad and open enough to admit a wide variety of interpretations.

The plot is simple. You are in a fantasy world where magic is dying, and a powerful figure known only as the Magus is dying with it. They bring together a group of adventurers to help them travel to the land of Umbra where magic was born. So far, it’s a fairly standard fantasy plot with little to distinguish it. The trick, however, lies in the game world itself. Along the linear path between the Magus’ home and Umbra are a variety of destinations with challenges and story prompts. When it’s your turn to move, you can make a choice to move your character to any one of these prompts and explore them in whatever way seems best to you.

This has two important consequences: one, it makes for a GM-less game where the players all have roughly equal say in filling out the lore of the gameworld. What is a “crabsinger” anyway? Who are the Stormguard? What is the prophecy of the Drowning Library? It’s amazing what happens when you and several other players sketch in answers to the foregoing. Second, it develops or tests the character in a tangible way each time; every prompt compels a story from the player.

In my play session, our epic adventure was less about the Magus or even magic itself than it was about coming to understand why the Magus chose us for this journey. Along the way, everyone’s character developed and changed in ways that were not entirely in our control. Some resigned themselves to impending death, others renewed their commitment to their families and loved ones. My character, a scholarly aide to the Magus, resolved to leave his service and reconcile with a lover she had left behind, as well as a family that missed her.

These are not necessarily earth-shattering stories, but the intimacy with which they were created, and the way our characters’ progress across the gameworld tracked their development, made the journey a profound one. Each session of Fall of Magic, then, is ultimately about what the adventure means; why are you all here and why are you all doing this? This is not new to PnP RPGs, and arguably it’s something many encourage players to do. But Fall of Magic puts those questions front and center, to the point where there is no game without answering them. Your journey has whatever purpose you collaboratively develop with your fellow players.

Fall of Magic’s enchantment lies in its ability to make each story prompt a launchpad for something greater than the sum of its parts, exploring how a single word can mean so many different things to so many people, and in the process making each step on the characters’ journey important and meaningful.

***

Fun Forge’s Tokaido, by contrast, is about the purity of the traveling experience itself; it makes a game of traveling for its own sake where the ultimate goal is to travel well. Named for the eponymous road between Kyoto and Edo (now Tokyo), you make your way from one to the other across the game board, stopping at various inns and temples along the way, meeting people, all while collecting odds and ends from your journey.

It’s a remarkable set-collecting game that makes only a pretense of competition between the players. Points are used to determine who ‘wins’ but what’s more important is how they seem to quantify the quality of your trip. You gain points for collecting souvenirs, trying different foods, and collecting picturesque vistas along the way.

In its placidity, the game reveals itself to be about the assembling of an experience. In this game no attention is given to why you all are making the journey to Edo in the first place, but in exchange it makes the journey the destination, if you’ll pardon the cliche. As a simulation of travel for its own sake it becomes meaningful in its own way, giving weight to the idea that a journey is what we make of it. The mechanics express the idea that travel is an opportunity to explore and try new things, not merely a necessary evil required to reach one’s destination.

***

What these games have in common is that they allow players to credibly make their own stories about why they’re traveling. But they’re also not “roaming around.” Just as in 80 Days, their journey is ultimately a linear one from Point A to Point B. This troubles me as a lover of open-world games; I greatly prefer the choice to walk off the main road and into the wilderness to see what I can see. In Fallout 4 there remains an exquisite joy in stumbling into a factory or office building and discovering little stories threading through the ruins, and therein lies hope for the genre--even if so much of the game seems devoted to denying that.

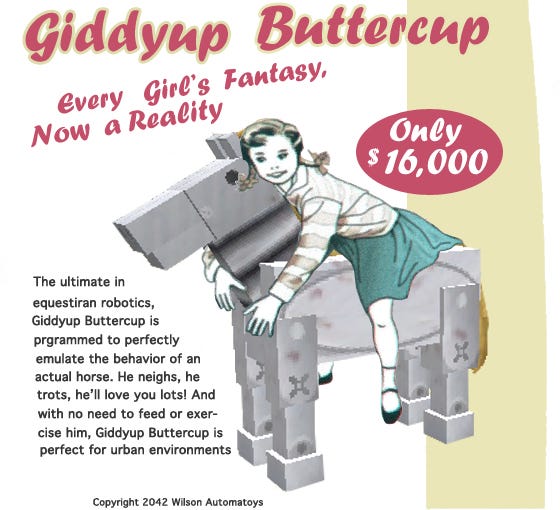

The “Giddyup Buttercup” nuclear-powered pony toy has its own story, for instance, some of which is told through letters, emails, and holotapes to be found in the wreckage of the Wilson Atomatoys headquarters. I’d been harvesting bits and pieces of broken Buttercups for their precious screws, but now I suddenly felt compelled to spare a few of them, if only in deference to the idealism of their creator. That meant something.

Sometimes the most profound things you can see and do in a video game are unscripted and unmarked by experience points or quest completion dialogue. They are unprompted choices you make, in a world that allows for that fuller, human response. That’s why I have two complete Giddyup Buttercups at one of my settlements, after all, off limits to scavenging.

Some things matter more than raw game mechanics.

The tools to make “wandering” a more intimate and human experience in video games--one that goes beyond petty rebellions like my Buttercup experience--are there, they just require further development.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like