Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

How to solve the problem of players loitering around, brooding on your gargoyles and refusing to have any fun!

I'd like to talk about cheese.

I was lucky enough to attend the Austin Game Developers' Conference in 2007 (before it was inexplicably renamed "GDC Online" - what's up with that?), where I attended Mike Morhaime's keynote address. Near the end of his talk he mentioned how important it was to eliminate "cheese" from the game.

"If there’s a most efficient way to play the game that will get you accomplishments faster, that’s what people will do, even if it’s boring and tedious. They’ll do it and think your game is boring and tedious and not fun –- try to eliminate those."

I've run into a couple of instances of people talking about "cheese" that they've experienced recently. On one of my favorite podcasts, the Giant Bombcast, during their 2009 Game of the Year deliberations, Jeff Gerstmann complained long and hard about the gargoyles in Batman: Arkham Asylum. His complaint boiled down to this: he could beat all of the stealth areas by jumping onto a gargoyle, waiting for one of the enemies to walk under it, then hanging down and tying that enemy up. He would then move to another gargoyle and do that again until he had taken out all of the enemies and beaten the area without ever taking a hit from any of the enemies. (Of course he had to wait minutes at a time sometimes for the enemies to pass under him, so it could be extremely boring to play this way; but that didn't seem to deter him from this strategy, since it had guaranteed success and zero risk.)

Blizzard worked hard to get cheese out of WoW.

On another podcast, Idle Thumbs (in episode #7 I believe), Jake Rodkin of Telltale Games told of a time when he and his friends had just failed repeatedly to beat a Left 4 Dead Expert-mode campaign. They were commisserating about how hard the game was when a programmer walked in on the conversation and said "Left 4 Dead? Man that's a great game but it's so EASY, even on Expert!" Turns out this guy had realized that no matter how many zombies were around, if you just backed into a corner and used the right-click melee knock-back ability with the perfect timing, you could always knock back zombies before they did damage to you, while still shooting (between each push) to do damage to them. "Man, that game would be fun - I hope they patch that out," he said, "because otherwise the game's just too easy!"

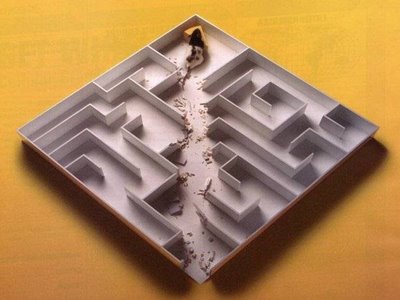

Like Rats in a Maze

So what is cheese? Well, think of both of these games as a possibility space - which is fundamentally what a game is, and what any game can be understood as. In the Batman example, the possibility space I'm talking about is driven by decisions like "Am I going to hide up on a gargoyle? Am I going to drop down and kick that thug in the face? Or am I going to wait until his friend isn't quite so close to him?" In the L4D example I'm talking about a possibility space driven by decisions like "am I going to stand out here in the open, or back into the corner? Am I going to fire right now? Or do a push-back? Or start reloading my weapon?"

So both of these are - or should be - very interesting possibility spaces... meaning that the decisions on how we navigate through them should be interesting, meaning that (by Sid Meier's possibly-misquoted but probably-true-anyway definition), we have achieved Good Gameplay! And the reason it's good gameplay is because the player is going to jump into this possibility space, try various decisions at various times in various orders - in order to get to the "I win" node of the possibility space... which is always the player's goal. The player is constantly defining and honing their strategy for what decisions to make when, trying to figure out the best way to navigate the possibility space.

Don't let players do this to your maze!

Now, in any such possibility space, the player IS eventually going to find the "optimal path" through your possibility space: the perfect strategy of what to do in any given situation, which will always eventually lead them to the "I win" state. When this happens, the player has mastered your game; and although you can extend your game's lifespan with various tricks, sooner or later the player is going to get burned out, get bored with your game, and move on. They have solved the puzzle you created for them, and it's only fun to play with a system that you've fully mastered for a while. Though some games like Tetris and chess have a profoundly rich and complex possibility space which are extremely difficult to master (and perhaps there is such a thing as a game that can never be fully mastered, at least not in one human lifetime), I think that it should generally be regarded as an inevitable part of your game's "life cycle" that the player will eventually master it and get bored.

The problem occurs when the player finds a "degenerate strategy." The book Half-Real defines this as "a way of playing a game that takes advantage of a weakness in the game design, so that the play strategy guarantees success." Personally I believe that there will always be at least one strategy that "guarantees success"; degenerate strategies are specifically ones that are simply much, much simpler than what the designer intended, and/or so simple as to make the game much less interesting to play than it should be.

Who's to Blame?

From one point of view, there's an extremely ridiculous element to all this: we want to grab that L4D-exploiting programmer and tell him "stop complaing about the game not being fun!!! You just said the game would be more fun if they patched out that trick - why don't you just stop using that trick and you'll have more fun!"

But as Morhaime pointed out: when the player finds this boring and tedious way to win the game, they will do it, period... and if it is a boring way to play the game, they will complain about your game being boring. As a game designer, of course, this feels unfair - you didn't intend for the game to be boring, you didn't intend for them to play it that way, and if they'd just stop playing it that way, it wouldn't be boring! It's not fair for them to blame you, it's their own fault, right?

Wrong. The player is doing their job: playing in your possibility space and trying to find the optimal strategy through it. It's your job to make that search challenging and interesting; and if an optimal strategy exists that is neither challenging nor interesting, then you have failed in your job, just as much as a programmer who had a bug in his code or a boat-maker who built a hull with a big crack in it.

How to Get Rid of that Limburger Smell

So how do you fix this problem? Sometimes the fix is pretty simple: in L4D2, you can only do the push-back move a few times before it becomes limited by a cool-down timer, making that action temporarily much less effective and forcing you to try something else. But how should Batman be fixed so that not every level can be solved by hiding on gargoyles and waiting to string a man up?

One direction would be to let the player keep this pet strategy, but begin to add exceptions that it can't be used against. For instance, they could have eventually introduced a new type of thug enemy that somehow can't be "strung up" at all, and mixed these in among the regular thug enemies. (This is the "Tower Defense" method of balancing.) Or they could have simply made using the gargoyles come with an associated risk, thereby breaking the dominance of this strategy in being zero-risk. In fact the team attempted this solution, by introducing a few gargoyles that turned out to be trapped with explosives. However Jeff Gerstmann found this to be a lame solution, because the rigged gargoyles were few and far between... and when they were introduced, the same one was trapped every time, so that he could simply avoid those specific gargoyles without actually modifying the rest of his strategy. Perhaps if gargoyle traps were randomized, their use would have been discouraged appropriately. However this kind of random element can introduce frustration to the player: when they're damaged by a randomly trapped gargoyle, they experience frustration because there was no way for them to know that THAT gargoyle was trapped - it's a failure with nothing the player can learn (i.e. nothing they could have done differently to prevent it), and that's a formula for player frustration.

Apparently cheese saved Batman's life?

Perhaps the best solution would have been to make the gargoyles begin to crumble after being used repeatedly, and/or after Batman sits still on them for an extended amount of time. This idea actually just occurred to me, but it seems like a good one as I can see several benefits it has:

It's thematically appropriate since the stone gargoyles already represent dilapidated architectural elements.

This mechanic could also interact with the stealth system of the game, as the sound of stone crumbling, or of a piece of stone falling to the floor, could alert the enemy to the player's position... negating the stealth that was the primary benefit of hiding on the gargoyles.

It would specifically negate the boring strategy of waiting around on gargoyles for a long time; but the gargoyles could still be used in any other (non-boring) strategies as they were before.

Finally, when the player used the gargoyles wrong and caused this "crumbling" failure, this failure wouldn't be frustrating; partially because it made sense in the world, but also because it's a failure they CAN learn from, and take into account in their strategies.

Again this seems like a good solution, and one that would force the player to go find another, more fun strategy. But who can say? It might have somehow created a different degenerate strategy, or exposed some other degenerate strategy that no one had noticed because they were too busy hanging out on gargoyles! In the end the only way to know whether something is fun is to play with it.

So to sum up: cheese is bad, and don't let your players abuse the gargoyles. Words of wisdom we could all stand to remember.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like