James Ohlen has been in the game industry for a while now – 20 years just at BioWare. Today, he’s design director of the EA-owned developer, looking over franchises like Mass Effect and Dragon Age.

James Ohlen has been in the game industry for a while now – 20 years just at BioWare. Today, he’s design director of the EA-owned developer, looking over franchises like Mass Effect and Dragon Age.

As design director of BioWare, he has to help communicate the creative vision of massive, sprawling virtual worlds to hundreds of game designers and other developers throughout the company – a significant task.

At Austin Game Conference today, he gave fellow devs a peek into the ideas and concepts that drive design at a large studio such as BioWare.

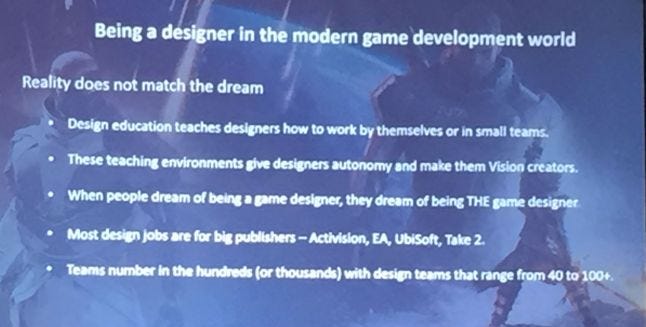

Dream vs. Reality of game design

“The reality often doesn’t match the dream,” said Ohlen, explaining to new designers that the game industry isn’t always what you might expect. Going to school, students might envision graduating and becoming the game designer, driving the vision for great games. But once they graduate, they instead might join a team with a hundred or more people, and the reality doesn’t meet their expectations. “It can be a tough adjustment” for some people," he said.

All slides from Ohlen's talk

All slides from Ohlen's talk

However, he said, “Don’t be discouraged,” and that game design is one of the most fulfilling jobs in the world, reminding the audience that millions of people may interact with your work.

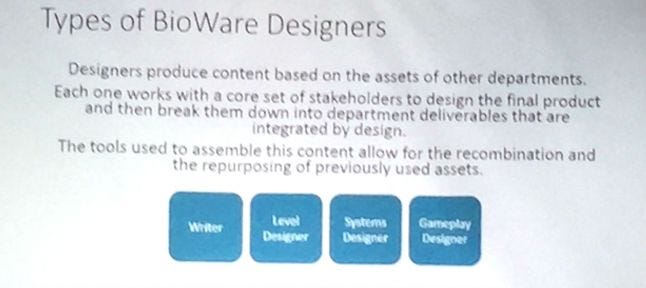

At BioWare, the types of designers are writers, level designers, systems designers, and gameplay designers. These positions require designers to break down broad concepts and turn them into something worthwhile.

BioWare is set up to train designers from the lowest level (an entry-level associate designer is said to be “level 17” within Electronic Arts) to level 22 (creative director). “You often have to let [new designers] make their own mistakes, or let them prove them wrong,” Ohlen said. He warned that more senior designers need to stay open to ideas from their more junior counterparts.

BioWare's writing team is about 20 people across three studios, said Ohlen, creating dialog, story, and narrative design.

BioWare's writing team is about 20 people across three studios, said Ohlen, creating dialog, story, and narrative design.

Level designers are the most abundant of designers at BioWare, and have one of the most stressful jobs, Ohlen said. “Level designers are essentially at the mercy of every single other discipline on the project...It’s a great job…like the ultimate Lego set…but that comes definitely with a lot of stress,” he acknowledged.

Systems designers work a lot with programmers and GUI designers at BioWare. Systems like game economies fall under their purview.

“A gameplay designer, out of the four disciplines, has to work the best with all the other disciplines…they’re working with everyone in order to be successful,” said Ohlen. Gameplay designers also have the important (and intimidating) job of creating the second-to-second gameplay upon which the game is judged by the public.

Quality of product vs. quality of life

BioWare’s mission statement is to make the greatest stories that you can play, said Ohlen, and its values are to achieve quality in workplace and product, in the context of humility.

Quality in product and quality of workplace can often be at odds when working in a large company like BioWare, Ohlen admitted. BioWare doesn’t want to “kill people for the sake of the product,” because everyone will be miserable and all your talent will leave. At the same time, the required work needs to go into a product in order to hit quality marks and stay in business. So the studio needs to be efficient as possible.

“I think humility is key to be successful” as a game designer, he said. Adding humility to your daily interactions can help with efficiency. He said being humble doesn’t mean being lazy or letting yourself be a doormat. Rather, it means that you believe there might be better answers than the ones you have. “I think it’s a designer’s job to find the best design idea for the problem to be solved,” he said.

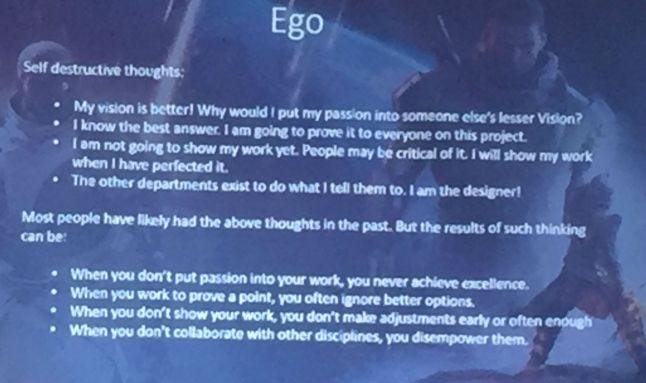

He said egotistical thoughts need to be “excised,” because that will cause your whole project to suffer. Don’t assume you have the best vision, don’t assume you have the best answer -- be willing to admit you’re wrong. Ohlen also said one of the worst things a designer can do is to hide their work from other people until it’s “perfect.” You need to get it in front of people early on and collaborate. “The ‘grand reveal’ never works,” he said.

He said egotistical thoughts need to be “excised,” because that will cause your whole project to suffer. Don’t assume you have the best vision, don’t assume you have the best answer -- be willing to admit you’re wrong. Ohlen also said one of the worst things a designer can do is to hide their work from other people until it’s “perfect.” You need to get it in front of people early on and collaborate. “The ‘grand reveal’ never works,” he said.

Ohlen continued to hit the subject of a designer being a humble problem-solver. “It’s one of the most self-destructive things [to assume] that just because of a word on your business card that you’re better at things,” he said. You might be thinking more about design and have more experience, but you’re not all-knowing, and you don't have all the answers.

“When you don’t collaborate with other disciplines, you disempower them,” he said. With that collaborative spirit in mind, here are the two roles of a designer, according to Ohlen:

You have to be amazing at understanding someone else’s vision.

You must be great at translating someone else’s vision.

Designing when the vision "sucks"

But sometimes when working on a big team where creative decisions happen above you, you might think a vision “sucks,” he said. All is not lost in this case, and one can still attain a passion for a vision and a project that they don’t initially agree with. But it takes effort:

Have empathy for the vision, its champion, and the intended audience.

Practice active listening (understand where they’re coming from).

Immerse yourself in the experiences most similar to the vision (play all your studio’s games, and play games, read books, and watch movies that align closely to the vision.)

In other words, he said, try to be positive and try to find ways to get yourself to love it.

Ohlen said he used to be one of “your annoying friends” who’re critical about everything. But he said he had an epiphany in the late 90s after watching The Matrix – and hating it while everyone loved it. He wondered if maybe being overly-critical was hurting his ability to enjoy…anything.

So he kind of turned that critical eye off to an extent, for the sake of simply enjoying things more. “Sometimes you need to turn off [critical thinking],” he said, while at the same time acknowledging it’s still important to be able to critique and analyze work.

As for reaching goals, Ohlen said every task has an ideal result, so being successful means identifying the ideal and knowing what the ideal is, always aiming for it, and often getting there via compromise. He said to never be discouraged if the ideal isn’t reached.

“[Falling short of the ideal] happens often and should be used as a learning experience and motivation to do better next time,” he said. “It’s just part of game development.”

Ohlen added, “All designers need to consider themselves problem-solvers. They should love problems.”

“Constraints do breed creativity,” he added. “If you don’t have restrictions you’re going to be doing the same things you’ve done before.”

There's always a solution

Identifying problems and finding the best solutions possible by any means is a theme that Ohlen hammered home over and over again. His mantra is: “There is always a creative solution to every problem ever. Sometimes you just don’t have time or money to find it.” Don’t beat yourself up if you can’t get there, but always be looking for a solution, he said.

Lastly he said to constantly improve. Plan, execute, check your results, review. Then start over again, taking your learnings from the previous cycles, and do better next time. He said the review part is often the toughest – you must listen to feedback and criticism, and be constructive with it. “It’s one of the most important things you can do as a designer,” he said.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like