Lead designer Henrik Fahraeus explains how Paradox Interactive's Stellaris combines the tropes of grand space opera with the dilemmas and political skullduggery of the studio's historical games.

Paradox Interactive, the Swedish studio behind grand strategy franchises like Europa Universalis, Hearts of Iron, and Victoria, have a long-established record of mining history for material and inspiration.

It's no surprise then that Stellaris, their sweeping 4X space-opera epic, also turns to history's cyclical tropes as it projects our distant future out amongst the stars.

Stellaris has proven to be a media darling, and has apparently sold quite well. It presents players with a galaxy apportioned by a number of distinct, hungry blocs in much the same way as most traditional 4X strategy games.

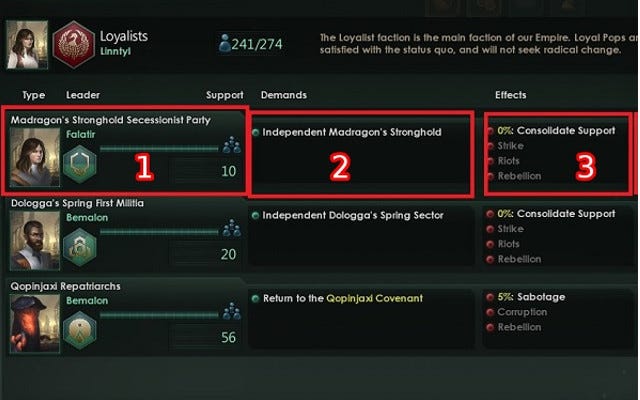

But its real triumph is how it takes things one step further, adding a layer of complexity to proceedings by making it possible--inevitable, really--for factions to develop INSIDE each of these stellar empires.

"Stellaris was always intended to be a sort of mix between a 4X game and a classic Paradox Grand Strategy game," says lead designer Henrik Fahraeus. "Having some form of political simulation is part of that tradition. Internal challenges like political parties and factions can help keep the later stages of a strategy game more interesting."

This focus on seeding the late game with interesting challenges is a crucial part of a strategy game's enduring appeal, and something that Stellaris does better than most. The way these internecine conflicts evolve and how they're linked to choices the player makes as early as the setup phase spawn fascinating late game scenarios. Each diplomatic action needs to be balanced not only against the desires of other empires, but also against the internal blueprint of your own.

"One of the most interesting things about Stellaris is watching a civilization develop within the boundaries of these systems (and poking your finger into the petri dish to try to guide that development)."

"It is a complex system and hard to describe succinctly, but it all boils down to two fundamentally important factors: Opinions and Ethics," Fahraeus says.

Ethics represent the core values of both system-spanning empires and individual factions inside those empires--what the game calls populations or "Pops."

"Both the 'Pops' and the various empires in the game have a combination of Ethics that make up their 'personality,'" says Fahraeus.

"Individualists don't like slavery and genocide, whereas Fanatic Collectivists might be fairly okay with it, for example," explains Fahraeus.

"Xenophobes don't like sharing a planet with weird and ugly aliens, and so on. Things like that will affect the Opinions that empires have of each other and the Happiness value of Pops (which is basically their opinion of the government). So, to sum it up: Ethos and Opinions drive AI behavior."

One of the most interesting things about Stellaris is watching a civilization develop within the boundaries of these systems (and poking your finger into the petri dish to try to guide that development). In the course of just one game of Stellaris, I watched my fanatically spiritual, individualist race of cat people become more and more fractured between a faction that craved simple freedoms and spiritual purity and others that longed to aggressively spread our culture to the unenlightened amongst our non-feline neighbors.

This internal tension pushed me to explore and expand at a rate faster than I might've had I been left to my own devices. After a convoluted sequence of observation and diplomacy with a neighboring race of space birds, a botched attempt to infiltrate their government led to a catastrophic war of attrition that left both of our empires in ruins.

Building complex, interlocking systems but ensuring that players have free rein to develop stories like mine is a staggering challenge, Fahraeus acknowledges. While the Ethics and Opinions mechanic is similar to those in other Paradox games, the team found they had trouble making factions unique and strongly distinctive, and didn't quite get to the level they wanted in terms of faction agency.

There was also some confusion between Factions, whose members are connected by shared ethics and demands, and Sectors, whose people are connected by their proximity within the different regions of an Empire.

"We wanted Pops to band together into Factions that could demand various things; freedom, for example," says Fahraeus. "We also wanted Sectors and their governors to sometimes strive for more autonomy. It feels like the two systems should be more integrated, but we never really came up with a perfect solution." He went on to suggest, however, that these were ideas Paradox hoped to expand on through DLC.

As it is though, Stellaris manages a rare feat: Successfully blending the exotic trappings of high space opera (space cows, laser weapons, primordial aliens) with the gritty, grounded political realities that humanity has faced throughout history. Whereas previous Paradox titles drew on the work of real-world economists and historians, Stellaris chose different sources of inspiration for its systems and conflicts.

"We did not have to attempt to model any historical events or processes. Instead, we threw in as many science fiction tropes as we could," Fahraeus explains. "But good science fiction is plausible and attempts to predict likely paths that the future might take, so in some ways it is similar to history,"

That isn't to say that Stellaris was developed in a vaccuum, or that our current political circumstance didn't shape design. "When trying to envision what the various combinations of Ethics in the game might correspond to, it is inevitable to think of various real world governments," says Fahraeus.

"For example, the Soviet Union would be Collectivist, Materialist, Militarist. The USA might be Fanatic Individualist, Militarist. Bhutan might be Spiritualist, Pacifist, Collectivist."

It's easy to start drawing similar correlations as a player. As my star kittens started to flesh out relationships with bordering empires, I caught myself thinking of the massive Collectivist empire of unidentifiable insectoid/lizard beings to my north as this future Milky Way's version of the People's Republic of China--they even had a bold red logo.

Mental connections like that are the beating heart of Stellaris' appeal, the beautiful alchemy of science fiction absurdities blended into one of the weightier political simulations in the modern strategy landscape.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like