Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Creating a fun stealth encounter is difficult, with bad execution resulting in players giving up on stealth. The following breakdowns lessons learned from working on 3 stealth games to encourage stealth gameplay and keep it feeling fresh and exciting.

Seven years ago, at Crystal Dynamics, I was given the opportunity to lead the stealth gameplay effort in the Tomb Raider 2013 reboot. Stealth was an area I had light level design experience in from The Bourne Conspiracy but Tomb Raider was a much more complex game. With help from a great Game Director, I was able to learn on the fly and deliver a working stealth mechanic and level design philosophy that was successfully applied across the game.

Fig: Lara Croft planning out her stealth options

What began as a small endeavor has turned into a six-year odyssey, including Battlefield Hardline and the recently canceled Visceral Star Wars game, where I have honed down my philosophy for creating fun stealth encounters. I am defining a stealth encounter as an isolated section of the game where the player is encouraged to takedown or sneak past enemies to achieve an objective.

Setting up a fun stealth encounter is very difficult and much harder to do than a combat-only encounter for two reasons:

Setting up a stealth encounter is complex and full of nuance. It is very easy to have minor issues that cause a player to completely give up on stealth and start shooting enemies. For instance, small bugs like missing cover or geometry incorrectly marked as see through can cause a player to be seen when they felt they should not be. A few frustrating instances like that can make a player give up on stealth altogether.

Designers must setup combat in the encounter as well, which means making a stealth encounter is usually twice as much work as doing a combat-only encounter.

The focus of the following article is on the complexity and nuance of setting up a stealth encounter; I am going to breakdown:

Encouraging players to play stealthily by making them understand how they can stealth an encounter

Classifying different encounters and the emotion they create

Pacing encounters in a level to keep stealth feeling fresh and exciting

Fig: Agent 47 deciding how to handle this stealth opportunity

Encouraging Players to Play Stealthily

Stealth is kind of funny in a way because there is a group of players that will always go straight to combat, no matter how well setup an encounter is. As designers, we need to accept that about 30% of players will fall into this category. However, we still need to do our best to encourage these players to try and play stealthily and support a fun experience for the other 70% of players. Stealth opens up many different ways for an encounter to be played and provides a more varied experience to the player. To encourage players to stealth through an encounter, they need to be able to:

Have a safe and readable starting point to form a plan

Understand enemy routes and behaviors as they move through the space

Easily identify useful traversal routes through the space

Creating a Safe Readable Start Point

All stealth encounters need to start in a manner that allows the player to form a stealth plan. Follow the below rules to ensure players navigate to a safe location without engaging an enemy to form a plan:

Players should hear a sound indicating an enemies’ presence before they are seen. Dialogue works well, but it could also be the sound of characters working, moving around, or any other sound that indicates the area up ahead is alive with activity.

Players need to enter their stealth movement set if the game does not have a crouch button, otherwise ignore this rule. This is the visual indication to the player that they need to be careful. In Tomb Raider, this is when Lara gets in her crouched movement set.

There must be an obvious hiding spot for the player to move to and assess the encounter. The spot must feel safe for the player to observe what is occurring on screen.

From the hiding spot, players should easily be able to see enemies, asses their his behavior and make their plan.

If a cinematic plays, the end of the cinematic should place the player in a hiding place.

Figs: Having a hiding spot at the start of an encounter is key to letting the player make a plan to overcome the encounter

Understanding Enemy Routes & Behaviors

Poor enemy placement is an easy way to ensure a player will never stealth through your level. Enemies that are too close together, enemies pointed too much towards player sneak routes and confusing enemy paths are all common failure points. The following rules help to avoid these and other pitfalls:

Enemies placed on the outskirts of an encounter should be easier to sneak past or takedown than enemies near the objective or goal of the encounter. That ensures the encounter feels more intense as the player gets deeper into it.

Avoid bunching up enemies unless for a specific purpose. The more you put enemies within death cry distance of one another, the harder they will be to kill stealthily.

Enemies should pause every now and then when patrolling or walking around. This gives players a chance to kill or move around them.

When planning enemy movement, deliberately make moments where an enemy may separate from a group and allow a window of opportunity for players to kill them. This also makes players feel rewarded for taking their time and observing their enemies.

Use dialogue lines that inform enemy actions so the player can anticipate where enemies will move.

Figs: Enemies that pause in easy takedown spots are a great way to reward player patience and draw the player into a space

Utilizing Clear and Readable Traversal Routes

Players need to be able to understand how to move through a space without being seen to encourage them to move forward stealthily. Follow the below guidelines when laying out your space:

Flat stealth spaces are rarely interesting and greatly limit creative gameplay decisions in stealth. Embrace verticality in stealth spaces. Going on a path that is below or above enemies gives the player a different perspective and promotes freedom and choice within the space.

Use cover to encourage players to move through the environment and draw them into the correct areas to solve stealth setups.

Fig: Notice how cover draws the player into the space and how there are obvious vertical stealth paths

Fig: Assassin’s Creed is a master class in using verticality in stealth

Classifying Stealth Encounters and the Emotion They Create

What I didn’t realize when I first started working on stealth encounters was the effect objective flow has on the emotional impact of an encounter. The pure placement of enemies and level geometry can evoke confidence, trepidation and fear. Understanding stealth encounters and the emotions they evoke is important because it lets designers pace out encounters in such a way to make gameplay feel less repetitive. A player bouncing between emotions will have a more robust experience than a player only experiencing one. There are four types of encounters for stealth I use: Outpost, Limited Approach, Hunted and Hide or Die. Each one has unique rules and evoke different emotions. The features of each are detailed below:

Outpost

In an outpost stealth setup, players start far outside the encounter and have a great amount of leeway as to how they approach and enter the space. Outpost encounters give the player a feeling of confidence because they pick how and where they enter the encounter. The player also can run away from the encounter and reset it easily, i.e. let the enemies cooldown and re-enter, unaware of the player. Far Cry 3 was the first game to have these encounters be perfected for me.

Fig: Far Cry 3 Outpost

There are four distinguishing features of an outpost encounter:

The player can see the encounter and enemies from at least 20 m away

The player has multiple vertical and horizontal path options to move around the space and engage the enemies

It is not difficult for the player to run away and disengage the enemies

The enemies are less dense outside than the inside of the encounter to draw the player in

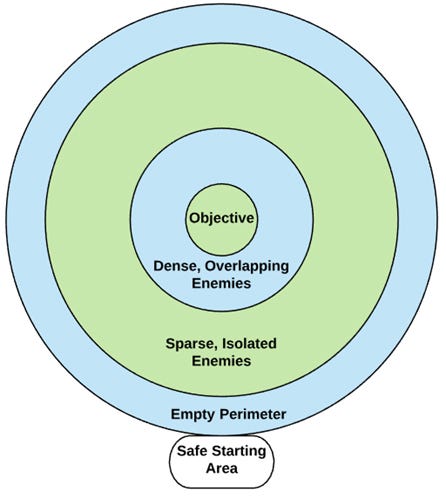

The below graphic visualizes the relationship between the player, level geo and encounter geometry:

The player starts in a safe space, moves through an empty perimeter and then must maneuver through an ever-increasing landscape of enemies to reach the objective. It is easy to run to the empty perimeter to escape enemies.

Example Breakdown

Let’s take a look at an example, here is a quick outpost liberation from Far Cry 3:

Notice the following events:

The player started far away and could form a plan of how he would engage the encounter

A lone enemy is in sight on the perimeter to make the player remain cautious as he approaches and help draw the player in

Once inside, the player moved around the space vertically as well as around lots of key sight blocking geo to overcome the enemies

This was a perfect playthrough, but it would have been easy for the player to run away and come back if he were spotted by the enemy

Uncharted 4, Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain, Assassin’s Creed: Origins and Battlefield Hardline also have some good examples. Notice the similarities in the three screen shots below:

Fig: Assassin’s Creed Origins Lakeside Villa Outpost

Fig: Metal Gear Solid 5: The Phantom Pain Outpost

Fig: Battlefield: Hardline Trailer Park Outpost

Other Gameplay Examples:

Uncharted 4 Madagascar Outpost: https://youtu.be/c_2EHkcUdtk?t=14m

Assassin’s Creed Origin Fortress Encounter: https://youtu.be/tc9bJmjODQI?t=1m3s

Metal Gear Solid 5: The phantom Pain – Hellbound Mission: https://youtu.be/k20E5r7Pry8?t=8m46s

Battlefield Hardline Trailer Park Encounter: https://youtu.be/ScbPCIy6kvI?t=6m18s

Limited Approach

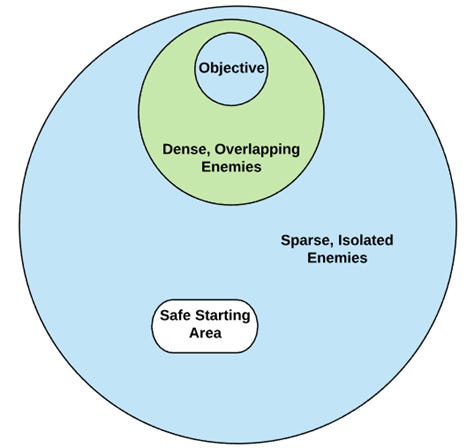

In a limited approach encounter, the player starts inside enemy territory. Not all enemies are visible from the encounter start and players must move through the constrained area to reach their objective. Limited approach encounters give the player a feeling of trepidation because the player has both a limited area to maneuver around enemies and an unknown number of enemies ahead.

Fig: Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty Tanker Mission

There are three distinguishing features of a limited approach encounter:

The player can see the enemies from at least 8 m away from his start point

The level geometry is slightly constricting and it is more difficult for the player to run away and disengage enemies for de-escalation than an outpost stealth setup

The player cannot see all the encounter enemies from the start point

Limited approach encounters are cool because the intensity of the encounter can be adjusted by changing where the player starts in relation to the enemies. That principle allows for two variations:

Variation 1

The player starts with the enemies in front of him and must move through the enemies to get to the objective.

Gameplay Examples:

Tomb Raider 9 Stealth Intro Level: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=538&v=tkEwAQTm29c

Last of Us 1 E3 demo: https://youtu.be/kbLOokeC3VU?t=3m8s

Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty – The Tanker Mission: https://youtu.be/Ox3Rz43Hhjc?t=5m22s

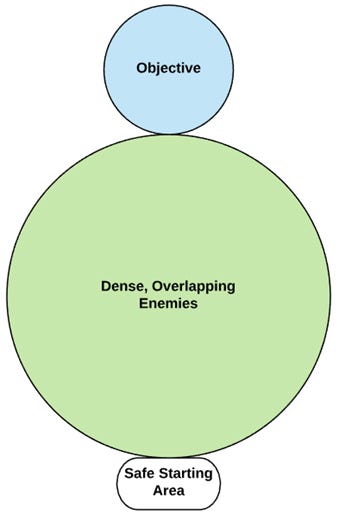

Variation 2

The player starts surrounded by enemies. Starting inside the encounter makes the setup more intense because of the player’s close proximity to enemies, fewer choices in the player’s angle of approach, and the necessity to make tactical decisions on the move. Since the player starts inside enemy territory, it is good to have sparse isolated enemies around the starting point. That allows the player to ease into the higher intensity encounter.

Gameplay Examples:

Battlefield: Hardline Chapter 9 Offices: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jDExp35QvhA

Example Breakdown

Let’s breakdown the Tomb Raider 9 stealth tutorial level (Variation 1 example):

The player comes around a corner, more than 8 meters away, sees an enemy illuminated by the spotlight

The player knows enemy activity lies ahead but does not have a clear idea of the number of enemies

As the player kills the first enemy and moves into the space, she gets a clearer picture of the number of enemies

The space is constrained so the player cannot easily walk by a bunch of enemies

Once fully into the space, the player has several traversal options but must endure tense moments to reach the objective

Edge Case Consideration

As I developed this theory, one of the challenging edge cases to look at was the stealth rooms from the Batman Arkham series. These are classic stealth levels; are they their own encounter type or do they fit within the rule sets I created already? Take the Stagg Airship level from Batman: Arkham Knight for example:

Video link: https://youtu.be/qeDi40O8-Ik?t=9m54s

Batman stealth rooms tend to be large and have lots of vertical and horizontal traversal options. The actual size of some stealth rooms are equivalent to the smaller Far Cry outposts and that causes confusion as to whether they should be classified as limited approach or outpost encounters. Notice from the top down map below that the player is locked into the room once they enter it and can only leave by one route.

Since the player is locked into a confined space and cannot run away and de-escalate a fight as easily as encounters in the open streets of the city, the encounter should be classified as a limited approach encounter. Yes, the player can throw smoke bombs and zip up into the rafters easily, but he is still limited to a few escape routes and does not have the freedom of escaping into an open unpopulated perimeter.

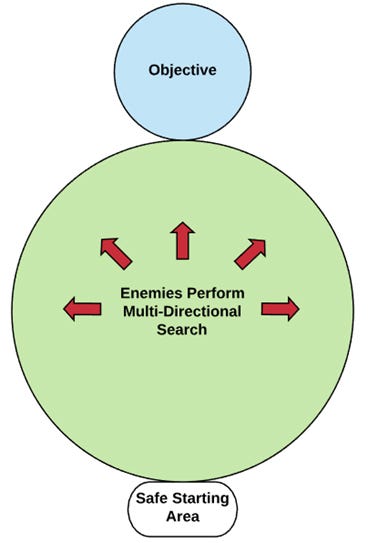

Hunted

In a hunted encounter, the enemies start off in an active search looking for the player. This type of encounter is essentially a limited approach encounter where the enemies start off searching for the player instead of being unaware. Hunted encounters give the player the feeling of fear because enemies are actively looking for the player. Instead of idly sitting around or slowly meandering through the world on patrol, these enemies know there is trouble and are on the lookout.

There are three distinguishing features of a hunted encounter:

It must be crystal clear that enemies are looking for the player at the start through dialogue and animation

The player can see enemies from at least 8 m away from the start point

It is more difficult for the player to run away and disengage enemies for de-escalation than an outpost stealth setup

Fig: An enemy searching for the player in Last of Us

Variation 1

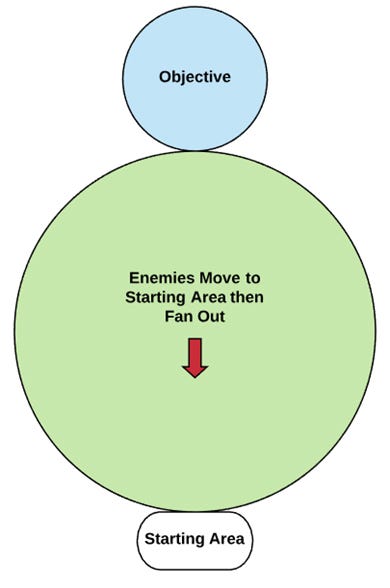

Enemies begin in front of the player's start position and move away from it. The enemies never move toward the start position to allow the player to assess and plan. As long as the player remains in the safe starting area, he has infinite amount of time to make his decision and so there is no time pressure.

Gameplay Example:

Tomb Raider 2013 Summit Forest Level: https://youtu.be/2NnM7Oncl0w?t=1m4s

Variation 2

Enemies begin farther away from the player's start position and move toward the player's starting position, applying time pressure. The time pressure adds intensity to the encounter because the player must make a plan quickly or he will be caught.

Gameplay Example:

Rise of the Tomb Raider Flooded Archives: https://youtu.be/rV1pJ-bVCoM?t=5m44s

Uncharted 4 Madagascar Encounter: https://youtu.be/ZVcCegSVZ64?t=5m50s

Example Breakdown

Let’s breakdown the Rise of the Tomb Raider example which is an example of using variation 2 (time pressure):

The player walks into a room and the player sees enemies repel in from the ceiling more than 8 meters ahead

When the enemies land, dialogue plays indicating the enemies are searching for the player and the enemies are playing obvious search animations with attached laser scope for added effect

The initial search point for the enemies is the player’s starting point. Upon reaching the player’s starting location, they fan out to random search locations thereafter

The player experiences great tension with the time pressure and must kill or hide quickly to get through the encounter

Hide or Die Encounter

A type of encounter that I’m not a fan of, but can be necessary for narrative or scoping reasons, is a hide or die encounter. If the player is spotted, then he is killed automatically. That is the only distinguishing feature of the encounter. I personally do not like these because they break systemic rules for stealth. Getting spotted should be consistent and remain the same throughout the game for system clarity. It allows players to go through the phases of teaching, testing and mastering a system. This hide or die encounter custom rule on being spotted can break that learning for players and frustrate them.

That being said, if used sparingly, these can be powerful encounters for the player to experience. In the below video from the Tomb Raider reboot, Lara needs to sneak past an enemy army. To get the feel of a large army, we used a bunch of lightweight NPCs, but that meant they couldn’t attack the player. If the player gets spotted by the army, then we kill the player automatically. In this case, the narrative moment of the player sneaking past a large enemy was worth the price of a moment of inconsistency. The below video shows the encounter: https://youtu.be/kVo01jsIcfY?t=20s

Fig: Lara sneaking past an army

Pacing Encounters to Keep Stealth Fresh and Exciting

One of the most powerful parts of the encounter types concept is using emotion as a method to distill stealth encounters into a more granularly to breakdown level pacing. Let’s look at an example case of a level with three stealth encounters. Without a concept like encounter types, a designer does not have many tools to articulate the differences in the three encounters. A common description method for this type of scenario is a designer saying a level has three stealth encounters that grow in difficulty. Difficulty is a good lens to use, but to get the most out a level, we need to go beyond difficulty and delve into the roller-coaster of feelings the player experiences in the level. Using encounter types, a designer can articulate themselves another way, “I have an outpost encounter to make the player feel confident at the start, then a limited approach encounter as they near the level midpoint to make them feel tense and the level ends with a hunted encounter to make the player feel fear.”

The above description is a great way to pace a level. It ensures the level does not feel repetitive because the emotional impact of each encounter is different from one another. I’m not saying difficulty should not be tuned. I am saying that difficulty should be tuned to fit the emotional impact of the encounter based on how far into the game the encounter exists.

Gameplay Example

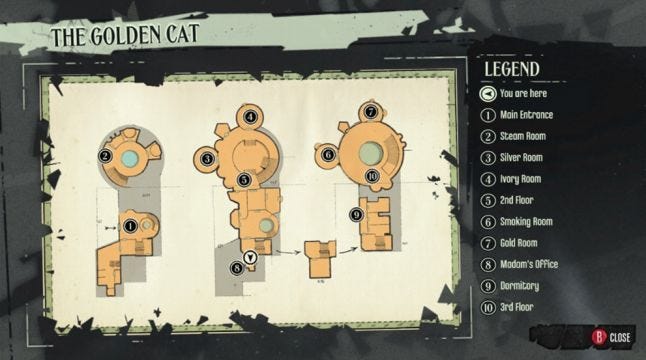

Let’s take a look at the application of this concept in action with the classic Golden Cat mission from the original Dishonored. The Golden Cat is a brothel the player must sneak into and reach an objective on the upper floor of the building. The outside of the building is an outpost encounter with lots of traversal options and different entrances into the brothel for the player to find. Below is a picture of the building the player must sneak into.

Fig: Golden Cat building from Dishonored

The player gets the confident feeling from the outpost encounter, but then the intensity cranks up as the player enters the brothel and must deal with limited approach encounters to reach the objective. Notice from the below top down map of the interior how the geometry pinches, which along with enemy pathing, create a tense feeling for the player.

Fig: Golden Cat Interior Top Down Map

Because the player is moving from a loosely populated open space to a tighter more densely populated space, the player goes on an emotional and intensity journey. Combine that with the comedy of finding your target in a silly compromising position, makes this one of the most memorable moments in the game. Watch the gameplay video here: https://youtu.be/v1TQPFCu830?t=2m47s

Conclusion

With a common rule set, we can ensure that players understand they are entering a stealth encounter and have the opportunity to make a stealth plan. By classifying and organizing encounter types, we are able to pace variety and emotion of stealth encounters within levels. These rules work for most stealth games, but special gameplay mechanics, enemies or map types could warrant adaptations or expansions of this methodology. Stealth encounters are difficult to bring to life but bring a lot of satisfaction through the varied ways they can be played. Thanks for reading!

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like