Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

What you see here is a starter’s guide to writing a story for a game. This is a simple step-by-step plan to making a viable game story. Not a masterpiece perhaps, but solid and adequate narrative material that is free of basic errors and flaws.

What you see here is a starter’s guide to writing a story for a game. This is a simple step-by-step plan to making a viable game story. Not a masterpiece perhaps, but solid and adequate narrative material that is free of basic errors and flaws.

This guide does not require any previous experience, skills or special knowledge to be used. It was specifically created for starters that have never written a script before – for programmers, designers, artists or managers.

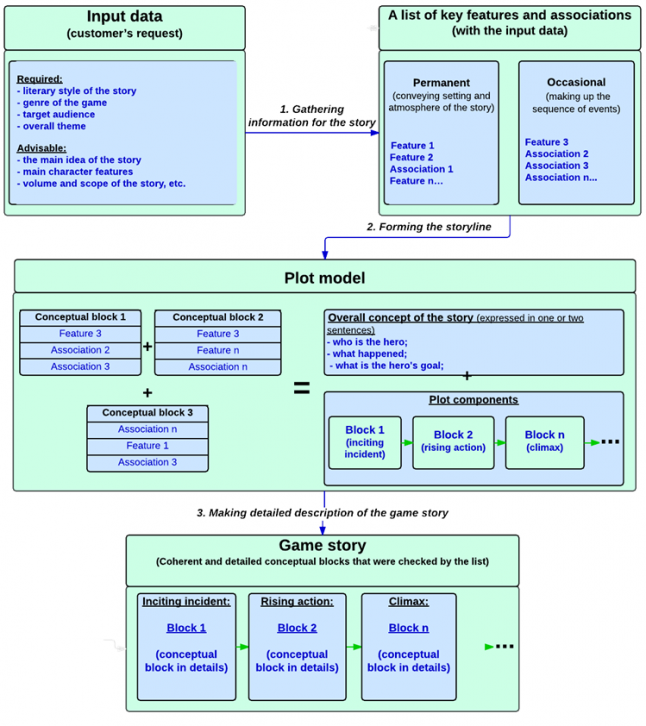

To get acquainted with the method, read the short version of the guide at first. It comes right after the introduction. The diagram below provides systematic description of the method, illustrating and schematizing it.

While working with this guide your may want to see more details on each of the steps. The detailed description is provided after the diagram – feel free to consult it whenever you need some explanation or examples.

Also, if your instinct tells you so, feel free to skip or modify some of the steps. No method can ever replace your individual experience and personality, quite the opposite: it must be used at your convenience to convey them into the story. Keep in mind that the major goal of this guide is to prevent you from some frequently reoccurring errors (and judging from the feedbacks so far, this goal was reached).

Hope you will find it useful too.

Diagram

The method in short

Step 1. Gathering the information for the story

The first step is tightly bound to the input data (game genre, literary style, target audience etc.) and includes three stages:

1. Studying the input data

2. Eliciting the characteristic features from the data

3. Comparing your list of associations with the input data

As a result of the above actions you ought to get a set of elements to build you story from. The characteristic features you’ve elicited from the input data, being put together with your associations will make up this set.

To elicit the characteristic features from the input data you should use both your personal experience and information you may find online:

After completing this step of the method you should have in you disposition a certain number of elements (words, phrases, sentences), and each element should be either a characteristic feature of the input data or your association with it. If so, you’ve done well.

We strongly recommend you to consult the checklist to step 1 and detailed example of completing step 1, to be sure you’ve done everything right.

Step 2. Forming the storyline

The most essential thing you get as a result of step 2 is the plot structure of your story.

If you have a key idea for the plot in your input data, use it. If you don’t have it, you shall create this little piece of text on your own.

Why do you need this? To make sure you’ll be able to put the quintessence of your story in one sentence. If you cannot construct such a sentence, it probably means you don’t have the full understanding of what your story will be about, which also means you are not yet ready to create a consistent plot[1].

If you don’t have any key ideas, you may regard it as an advantage of a sort: you are in your own right to construct your plot independently. Use the elements you’ve got after completing step 1.

If you feel a bit confused, you can return to step 1 and do it all over again, because material you elicit during step 1 is crucial for your further work.

When this is done, you have a set of elements on your hands – 10 elements, 12, 27, 44, 18 – whatever, depending on how many characteristic features and associations you’ve elicited and have written down. A ramified plot with a huge amount of content for many hours of gameplay will require more elements. Likewise, a small story for some less ambitious project will require fewer elements.

Read through the elements that you have. Group them together, combine in every possible way. These combinations will give you some ideas for your future story. Still you will not see the complete storyline yet. Continue your experiments and regroup the elements until you have enough events before your inner eye to say: «This is it. Now I know what my story is about and who’s the hero”.

It means you have the key concept. Be sure to right it down.

At this point, you already have a number of combinations, you have some key points of the plot and the overall idea of what the story will be. The substantial part of work is done.

Now, depending on various aspects (such as, for example, the duration of your game – how much do you need? one-hour gameplay? or is it 8 h, or maybe 24 h?) you have to structure your story.

The more ramified plot there has to be, the more parts it will consist of. A short story for a small game needs nothing but a simple structure – a couple of parts for each: the exposition, the rising action, the climax and denouement. Such pattern worked good for NES game Adventures in the Magic Kingdom.

But a big project such as Warcraft III: Reign of Chaos requires more complex story arc, because its plot includes several branches of the storyline, and you must think thoroughly through how many parts you shall devote to each fragment of the structure. And the overall number of such fragments may happen to be pretty big. For instance, 2 parts for exposition, 1 for inciting incident, 18 for rising action and so on, which makes over 20 in total.

Following the above logic, break your structure into a certain number of parts. Try to stick to this structure while completing step 3. To check yourself, be sure to consult the checklist to step 2 and detailed example of completing step 2.

Step 3. Giving detailed description of the plot

At this point, you must already have:

a set of elements elicited during step 1;

key concept and the structure of your story (results of step 2).

You may already have details for some parts of your story as well. If so – good. If not – it’s fine too, because unwinding and detailing all parts of the structure is actually a task for step 3.

Ready-made plot is what you will get after completing step 3. You have in fact done all the work while getting to step 3.

At this point, you probably know the answers to the following questions:

How many parts does your story consists of?

How many parts is devoted to each of the plot structures (inciting incident, rising action, climax and denouement)?

What is your story about? (key concept must reflect this)

And one of the most important questions – which combination of elements corresponds to each part of the plot structure?

While combining the elements during step 2 in order to create the key concept and/or decide about story structure in general, maybe you have already written more details on some parts of the story (or just thought them through in your head). Now is the time to do it intentionally and necessary in writing.

The parts of the story that come into your head when you’re mixing the elements together, are surely related to certain parts of structure that emerged during step 2.

Outline them.

Look for the plot parts that do not yet have any related combinations of elements. If haven’t got the grasp of what should be the contents of these parts, try combining some elements that fit in logically. There is a high probability that this will lead you to the content you need for your story and will give you something to fill the gaps.

In case you don’t have corresponding sets of elements to fill the gaps and you don’t need them to do this (you can manage without them, you already know how to implement these parts of the plot), you don’t have to waste your time. Work on these parts as you feel fits.

See how many parts there are in your plot structure. Evaluate how many of them you have already written. If it is complete (and you don’t have desire to broaden or reduce the structure), then you have one final (and pleasant) step to take – carefully read your story and honestly say if it is good.

If you worked hard enough and carefully followed this method, there is a good chance that you now have a quality story with a decent plot, which satisfies the requirements of both logic and the input data.

Now your main task is to eradicate all inconsistencies (which you will probably find when reading your story top to bottom) and make sure it meets the requirements of the input data: literary style, theme, target audience, and, last but not least – game genre[2].

The result of successful completion of this procedure is complete and viable game story.

Consult the checklist to step 3 and detailed example of completing step 3, to make sure you’ve done everything right.

Detailed description of the method

The method consists of several steps. To complete each of the steps you will need certain input data, and to succeed you have to do all the tasks presented in a checklist[3] for each particular step.

Step 1. Gathering the information for the story

To create your story you certainly need some input data to begin with. These data can describe various aspects of the future story, starting from hero’s personality and ending with synopsis.

However, there are some key aspects, which are indispensable: if you don’t have them, you cannot start working on the game’s story. Such aspects include game genre[4] (platformer, interactive fiction, etc.), literary style[5] (comedy, detective fiction, etc.), target audience (18+, women over 50 and so on), and overall theme/setting[6] (zombie apocalypse, battles in space).

Each of them possesses its own unique characteristic features that allow to distinct it from other similar categories.

Example:

characteristic features of fantasy style are mythical motifs and fairy-tale tropes, fictional world similar to real Middle Ages; supernatural creatures or phenomena, etc.

characteristic features of plarformer as a game genre include moving platforms, jumping over the obstacles and so on.

It is important that neither of the story parts would contradict these characteristic features. To clear things up use different sources of information:

However, even when you have sufficient input data and a full list of characteristic features, we cannot say you have everything you need to make a story.

To complete all of the above, you need your own associations with the content. Individual connotations these data invoke will help you to make your story unique and original, with a touch of author’s personality.

Example:

Suppose, all the information you have is the key word “Italy”. Different authors will have completely different associations with it. The first person may recall pizza and pasta, the second one will depict Rome, the third person will think of leather and shoe factories, and the forth one will imagine Pinocchio.

Making the list of association may be of great help in story writing. Keep in mind though, that your associations must not be in conflict with the desired genre, literary style or target audience age rating. If you need a quality horror FPS, then associations with winged pink ponies will probably be less than useless.

Thus, you’ve worked with the input information and now you have a long list of characteristic features and personal associations. You may now try to divide them in two groups: something that will be present throughout the whole story and something that will only appear occasionally. Setting and ambiance form the first group, the events of the plot go to the second one (the incidents and conflicts that will shape the storyline).

Example for the locked room mystery:

constant: old manor somewhere in England, murder investigation, mysterious writings on the walls (it means that the whole story will take place inside the walls of the manor, the murder investigation will be the main theme that will link the events in one storyline, and the writings on the walls will persistently reappear throughout the whole story).

occasional: the doorkeeper, the cook, herbs and poisons (in means that doorkeeper and the cook will only appear in some parts of the story, and only a few events will involve them; for example: the cook spikes doorkeeper’s meal to get rid of the witness).

When you already have your table of features and associations divided in two, the first step of this method is complete.

Check-list to step 1:

1. Customer provides a complete set of requirements to the future story.

2. These requirements contain information about game genre, literary style, target audience and overall theme of the story.

3. For each component of the input data, you find characteristic key features.

4. You make a list of all associations with the input data.

5. No association must be in conflict with characteristic features you’ve elicited earlier.

6. You divide the list of characteristic features in two groups: constant and occasional.

Step 2. Forming the storyline

The aim of step 2 is building up the storyline, i.e. understanding and outlining the order of events in general. The table of characteristic features and associations, the key concept[7] of the plot and the basic knowledge of story arc[8] (understanding what are the inciting incident, the climax and the denouement) will be your aid here. If necessary, consult relevant resources.

Sometimes you may find the key concept of the plot and its short description among the input data (or you could generate them while working with characteristic features and associations). If you’ve been having them from the beginning, then your work here is easy. Take the givens, broaden and deepen the concept, complete it with characteristics from the Constant part of the table and events from the Occasional part.

If you succeeded in creating consistent interrelated sequence of events, you can say that you’ve done half the work for step 2.

Yet you still have another, equally important part of the work to do – creating the framework structure of this sequence.

Firstly, you must determine how many and exactly which segments you plot will consist of. To figure it out, you have to get the grasp of the project’s scale and format. To illustrate: compare the story for the classic game Darkwing Duck (total of 7 locations, small number of characters and events) and the story of Dragon Age: Inquisition (vast world with immense number of NPCs and variety of quests).

Darkwing Duck’s story structure can easily be reconstructed. Strictly speaking, the plot is primitive. The inciting incident is represented by one block that player learns from the cut-scene. Then there comes the main action represented by seven locations, requiring seven different blocks. And there’s one more final block for denouement of the story that is given in the final cut-scene.

Reconstructing the story arc of Dragon Age: Inquisition in similar way would be a much harder task, which will require huge amount of text. It is enough to say that the arc would consist of greater number of segments and each segment would contain even more conceptual blocks[9]. For such project the total number of blocks may reach 50 and more.

That is why you should work on the story structure taking into consideration the specific features of the project, the intended gameplay time, game genre and so on.

Will the inciting incident require one conceptual block as in Darkwing Duck? Or maybe the introduction of your project will be more like the one in Syphon Filter (great number of incidents taking part simultaneously within the location, different fractions present in the area at the same time, many characters of various importance for further gameplay, etc.)? In which case you will probably want to devote more blocks for the inciting incident, maybe even 5 or 6.

By the way, if you do not know the exact scope of the story, keep it as simple as you can – don’t waste your time and creativity on many volumes of narrative. Create a short and sketchy story. If it proves itself worthy, you can always expand it.

With all this in mind, break your storyline into independent conceptual blocks and indicate which blocks will form the exposition, the inciting incident, the rising action, the climax and so on.

If you don’t have the ready-made concept among your givens and you don’t imagine it clearly either, you may work on the storyline another way.

Just look at the table you’ve created earlier and imagine in what way different features and associations may click together. What exciting events you may get by combining various characteristics, what is the connection between them.

Example for the locked room mystery:

Such characteristics and associations as doorkeeper, murder, poison, cupboard, cook and a key may be combined in a variety of ways:

1. (doorkeeper, murder, poison) – the doorkeeper was poisoned; (cupboard, cook, key, poison) – they’ve found the key to the cupboard, where the poison was kept, on the cook.

2. (doorkeeper, murder, cook) – the doorkeeper has murdered the cook; (cupboard, key, poison, doorkeeper) – the doorkeeper has unlocked the cupboard with the key, took poison and died.

3. (doorkeeper, cook, murder) – the cook has murdered the doorkeeper; (cupboard, key, poison, cook, doorkeeper) – the cook opened the cupboard with the key, took out the poison and placed it in doorkeeper’s hand, so everyone would think it’s a suicide.

4. (doorkeeper, cupboard, cook, murder) – doorkeeper has found cook’s dead body in the cupboard; (poison, key, doorkeeper, cook) – the doorkeeper has taken away the poison he found in the hands of a corpse and locked her up in the cupboard again, saying nothing to anyone.

5. and so on.

Mix it up, combine and regroup features and associations. Line up your events in different sequences and choose the most interesting. When you have found the sequence that seems to you the most promising, break it into conceptual blocks and define, to which part of the story arc (inciting incident, climax, postposition, etc.) each block corresponds.

With this done, try to write down in the shortest possible way (one or two sentences) the key concept of your plot, which answers three main questions: who is the hero, what do they want and who hinders them.

Step 2 may be considered complete when you have the key concept, the storyline formed from the list of characteristic features and associations, and when the events of the storyline is distributed accordingly through the story arc (you know in bare outlines what happens as the inciting incident, as climax etc.)

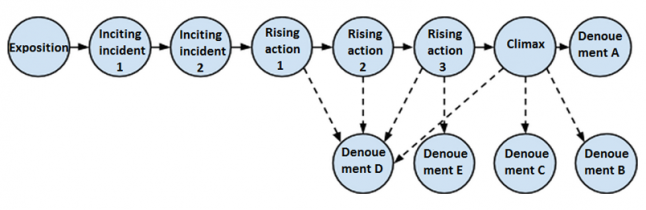

NOTE! If you want to create a branching story with different endings (or any other type of non-linear story, you may want to draw a clear graphic scheme of such story).

Check-list to step 2:

NOTE! The order of actions may vary and be different from the following pattern.

1. Group characteristic features and associations together in conceptual blocks.

2. Link the conceptual blocks in the storyline.

3. Make sure the events of the storyline are not in conflict with the input data.

4. Make sure the events of the storyline are not in conflict with the typical features and associations you’ve emphasized as the Constant ones.

5. Each conceptual block corresponds to a certain part of the story arc.

6. You can state the essence of each conceptual block in one sentence.

7. The conceptual blocks are linked together in a logically consistent sequence.

8. You have the key concept of the story outlined in a couple of sentences.

9. You have a diagram for a non-linear story (if you plan it).

Step 3. Giving detailed description of the plot

By completing this step, you will expand your storyline and detail each of the conceptual blocks – that is, you will write your story, making it ready to be perceived by the audience.

If necessary, you can always go back to the previous steps of this guide and make changes to your storyline or add some new associations to the list, and then get back to the detailed description.

When making your story, you should remember that it is meant for the game, so it must meet the specific requirements of the industry. Thus, the following tropes are strongly not recommended:

It all was in vain!

Example: the player leads their character through all twist and turns of a story branch for a long while, overcomes all obstacles and eventually finds… a dead end with no reward for all the efforts.

Using this trope, you make your player feel as if all they did was useless, and thus comes disappointment and frustration. Classic example: “Your princess is in another castle”.

You lost!

Example: At the end of the game, the player sees the final cut-scene that concludes the story, where the main character suddenly gets killed.

When the game ends in player’s defeat and they don’t have a chance to change it, there is a high chance that the player will never play it again and will leave negative reviews. The end of Mass Effect III illustrates it very well.

It’s the other way around!

Example: A pet the player has been taking care of during the game turns out to be an envoy of hell and slays the entire family of the main character.

You can’t just ruin the world you have built for the game and break your own pattern.

Illusion of choice

Example: The player has been offered several options and feels that the advancing of the story depends on their choices. But when they try to play once again and attempt other options, it turns out that the choice is sham and makes no difference whatsoever.

If you can’t make player’s choice meaningful, giving them the false feel that they are directing the story is risky.

Also you should not forget that you’re actually writing a story – not a script, not a or game mechanics[10] or gameplay description.

Example:

- wrong: “…jumping over the obstacles and using the liana-climbing skill they rushed towards him”;

- ok: “…risking to fall down into the chasm they rushed towards him”

- ok: “The passengers have searched the boat through and through, but haven’t found any crew members, what they have found out though, is that all rescue boats were missing and the engine was broken”;

- wrong: “The hatch of the nearby manhole shoots out and from the stench nowhere emerges Paster with a grenade clutched in his hand. Riser shouts: “Cease fire!” Paster headlocks him from behind, throws the grenade at the tommy-gunners and puts his gun to Riser’s head: “Cease fireeee!”

Your story must be free from superfluous details. You can check you story for them by trying to articulate each conceptual block of the plot in short sentence. If you can’t do this, it probably means that the block is somewhat watery and you should edit it or break it into two or more blocks.

Ideally, your story should convey in a coherent and clear way the sequence of events and their causes.

Check-list to step 3

1. Expand each conceptual block.

2. Make sure the overall story meets the input requirements.

3. Make sure the plot is free from logic errors:

all characteristics and associations are used legitimately;

all conceptual blocks are linked logically by the cause-and-effect relationship

the conceptual blocks do not contradict each other and correspond with the narrative goals[11]);

each event has its cause that is clear from the story.

4. Make sure you are consistent with the scale of the plot: your story neither comes down to the script details (overly specific), nor comes up the key concept generalization (not specific enough).

5. Complete the story arc description with a diagram.

6. Make sure your story does not describe game mechanics directly.

7. Stick to the main goal that motivates the hero’s actions throughout the story.

8. Check if you can articulate the essence of each conceptual block in one sentence.

9. Make sure your storyline is free from the “forbidden” tropes, unless their use is justified by your goals.

Finalization

If you’ve been making your story along with studying through this document, you probably have it ready by now.

Chances are that it can be used to make a game right away. Maybe that is what will happen after some adjustments and tweaking, or maybe it will go on the shelf to wait for its time to come.

Its fate is not decided yet, and it is rather up to the customer, not to you, to decide it. Anyway, there’s a lot of work to be done to implement your story in the game: protagonist and antagonist character design, supporting characters design and working towards unity of form and content by exploring the ways of conveying your story through gameplay and finding narrative elements[12] to implement the plot and many more.

This work is as important as the story design itself – the successful implementation depends on it greatly. It is actually worth a separate guide devoted exclusively to this stage of game story development, which is yet to come.

Detailed example of story development

Input data:

Required:

literary style – social sci-fi

game genre – survival simulation

target audience – 18-24 years old

setting information or overall theme – nowadays, one of typical post-Soviet million-plus cities, bedroom district, an attempt to convey the ambience of the block.

Advisable:

main character features – not a humanoid.

Step 1. Gathering the information for the story

Socio-philosophical sci-fi

Characteristic features:

fantastic assumption (as a hallmark of sci-fi style);

effects this assumption has on society and/or individuals;

all events have scientific (not mythical) explanation;

intended or accidental social experiment;

depiction of human relations in society;

studying of global and humanistic problems;

warning of dangerous social trends.

Associations:

contact with extraterrestrial intelligence;

human being as involuntary aggressor;

xenophobia;

no clear and unmistakable solution to a problem set.

Survival simulation

Characteristic features:

hero cannot attack or their ability to attack is restricted is some way;

hero is surrounded by many dangerous enemies;

character survives in conditions of isolation or/and supply shortage;

one of the ways to survive is to establish contact[13];

the main survival tactic is avoidance behavior.

Associations:

characters find themselves in extraordinary circumstances;

dodging;

looking for the safest way;

detached view – kinsmen give advice through some kind of communicator;

one of the ways to survive is to establish contact.

TA – 18+

Characteristic features:

can contain: information that justifies unacceptable or improper behavior and denies family values, as well as extreme portrayals of violence or drug abuse;

content that invokes intolerance and hatred;

strong language;

can contain stronger sexual themes and content, graphic nudity, pornographic content.

Typical block in post-Soviet million-plus city

Characteristic features:

the inhabitants of the block have to take daily trips to the city or industrial areas where they work, and return home just to sleep;

remote and isolated, no objects of city-wide importance;

bleak style of housing development with identical apartment houses;

minimum maintenance infrastructure (stores, schools, clinics, recreation areas);

ramified municipal transport system.

Associations:

playgrounds/yards within the “well-holes” of houses;

car sheds in the backyard;

dumpsters, trash scattered around;

24h kiosks and stands;

stray cats and dogs;

hooligans and boozers;

emotional monotony, anxiety;

patched and repaired, yet broken again benches.

Non-humanoid character

Characteristic features:

physical and moral qualities which are not typical of humans;

Associations:

lacks some body parts typical of humans;

has a body of different tactile perception (e.g. viscosity or immersion);

feels when someone is frightened, this feeling slows down the metabolism and inhibits vitality of the creature;

some other physical peculiarities: absorbs food with its body surface; feeds on natural fibers, wool, fleece and hair; gradually shrinks, loses body parts and health due to contact with water, human screaming makes it explode (body parts grow back together again);

some inconceivable flight and teleport abilities based on emotions.

The results of step 1: List of characteristic features divided into constant and occasional

Constant | Occasional |

|

|

Step 2. Forming the storyline

Generating the plot concept[15]:

An absent-minded tourist (a representative of alien civilization) due to the teleport malfunction ends up on Earth, in block of a post-Soviet million-plus city, where faces the challenges of a typical human society and is forced to struggle for its life and seek means for survival.

Grouping elements into conceptual block[16]

Combining different elements from the list, which are connected through associations and/or logically.

Block (alien on the playground, in the sandbox)

playgrounds/yards within the “well-holes” of houses;

depiction of human relations in society;

contact with extraterrestrial intelligence;

human being as involuntary aggressor;

hero is surrounded by many dangerous enemies;

the main survival tactic is avoidance behavior;

dodging;

one of the ways to survive is to establish contact;

can contain: information that justifies unacceptable or improper behavior and violence;

trash scattered around;

human screaming makes it explode (body parts grow back together again).

Block (alien teleport comes out of order because of the emotional impact of human civilization)

fantastic assumption (as a hallmark of sci-fi style);

emotional monotony, anxiety;

Block (alien in the dumpster, hobos (?))

xenophobia;

playgrounds/yards within the “well-holes” of houses;

the main survival tactic is avoidance behavior;

dodging;

one of the ways to survive is to establish contact;

strong language;

can contain: information that justifies unacceptable or improper behavior and violence;

trash scattered around;

character absorbs food with its body surface;

character feels when someone is frightened, this feeling slows down the metabolism and inhibits vitality of the creature;

human screaming makes it explode (body parts grow back together again).

Block (puddled road after the rain and moving vehicles)

looking for the safest way;

trash scattered around;

the creature gradually shrinks, stiffens and loses health due to contact with water;

no clear and unmistakable solution to a problem set.

Block (gangs of hooligans rumble and alien gets involved)

content that invokes intolerance and hatred;

strong language;

can contain stronger sexual themes and content, graphic nudity, pornographic content;

car sheds in the backyard;

emotional monotony and anxiety;

trash scattered around;

hooligans and boozers;

character absorbs food with its body surface;

character feels when someone is frightened, this feeling slows down the metabolism and inhibits vitality of the creature;

human screaming makes it explode (body parts grow back together again).

Block (something traffic-themed)

the inhabitants of the block have to take daily trips to the city or industrial areas where they work, and return home just to sleep;

ramified municipal transport system;

human screaming makes it explode (body parts grow back together again).

Block (the emotional ambience hinders the alien and prevents it from finding the solution to its problems, still it has to make the decision).

there is no clear and unmistakable solution to a problem set;

emotional monotony and anxiety.

Arranging conceptual blocks into coherent storyline; defining the main idea of each block[17]:

Story arc part | Theme/name of block |

Inciting incident | Tragic teleport malfunction (emergence of the alien on Earth) |

Rising action 1 | Crash location – yard full of puddles (panic scoot) |

Rising action 2 | Deadly football game (encounter with the local kids) |

Rising action 3 | Dangerous road (moving vehicles) |

Rising action 4 | Children, their mothers and xenophobia (in the sandbox) |

Rising action 5 | Life in trash dump (hide and seek among the dumpsters) |

Climax | Car sheds, hooligans (beyond the edge of life) |

Denouement | Ambiguous ending (hibernation of hope) |

The overall results of the step 2:

Key concept: An absent-minded tourist (representing alien civilization) due to the teleport malfunction end up on Earth, in block of a post-Soviet million-plus city, where faces the challenges of a typical human society and is forced to struggle for its life and seek means for survival.

Story arc part | Theme/name of block | Elements for the blocks |

Inciting incident | Tragic teleport malfunction (emergence of the alien on Earth) |

|

Rising action 1 | Crash location – yard full of puddles (panic scoot) |

|

Rising action 2 | Deadly football game (encounter with the local kids) |

|

Rising action 3 | Dangerous road (moving vehicles) |

|

Rising action 4 | Children, their mothers and xenophobia (in the sandbox) |

|

Rising action 5 | Living in a trash dump (hide and seek among the dumpsters) |

|

Climax | Car sheds, hooligans and desperation (beyond the edge of life) |

|

Denouement | Ambiguous ending (hibernation of hope) |

|

Step 3. Giving detailed description of the plot

Block 1. Inciting incident. Tragic teleport malfunction (emergence of the alien on Earth).

An alien tourist hits the emotional whirlwind, loses control of its emo-teleport, which uses the emotional waves in its basic settings, and crashes on Earth. Physiology of its species allows the tourist to survive after falling from a great height – the impact makes it lose most of vitality, but tones up its cells, so the creature takes form of a springy ball and lives. The only communication with creatures of its kind is trough telepathic transmitter, by means of which they give advice on survival until the emo-teleport is fixed. The problem is that the place the tourist crashed in is imbue with anxiety and fear, which affects badly both the emo-teleport and the creature itself.

Block 2. Rising action. Where to hide? or The Earth opens its wet embrace (panic scoot).

The site of the crash turns out to be a deadly trap – the place where the creature lands is soaking wet from the rain that bucketed down recently, and the water is a grave danger to the alien, because it makes its body shrink and lose parts. The teleport ought to be repaired, of course, but the more pressing task now is finding the way through numerous puddles to the safe dry place and regaining the regular form.

Block 3. Rising action. Dangerous road (traffic monsters)

Trying to escape water, the alien tumbles up on the highway. The roaring of traffic deafens it, and it immediately gets hit by a car. With a loud thud it flies over to another car, and then another, and another. Our hero is in pain, each hit drains its life power, roaring motors and honks literally tear its tiny wobbling body to pieces… Can it be there’s no escape from these soulless metal-and-plastic monsters? Here they are, scorching towards the alien at frightening speed, ready to squash, tear to pieces, devour!.. No! One must pull oneself together… [18]

Trying to escape water, the alien tumbles up on the highway, where it immediately faces another challenge – not only must the creature maneuver through the puddles and avoid being showered by muddy water, it also must dodge the monstrous cars, threatening to squash it to death.

Block 4. Rising action. Deadly football (encounter with the local kids)

Finding itself at last on the lush green grass, the extraterrestrial traveler is safe for a while, but it needs to restore its energy, so it starts looking for something to eat. Suddenly, a group of strange creatures appears ahead, and creature smells a faint scent of food. Led by its hunger and the advice from the telepathic transmitter, the alien moves towards humans. But before it has a chance for some refreshment, they decide to play football – with the alien as a ball. Our hero is nearly unconscious as it is, in addition kicking and shouting of the kids make it explode. When they realize, their “ball” is rather unconventional, they become frightened (which badly affects the alien) and they start throwing stones at it.

Block 5. Rising action. Children, their mothers and xenophobia

The tourist manages to escape, but it is weak and tired, hunger affects its ability to coordinate its movements. It smells tantalizing scent of food again and makes its way to the source of the aroma. Without realizing it, the alien finds itself in the sandbox, among children playing there. It cannot cope with hunger and flings itself on the food, which turns out to be clothes, fabrics and kids’ hair. Children are not afraid of the alien, but their mothers are, and fear is poisonous to our hero. They yell and trample it, they infect their children with their own fear. The only thing left is to escape, but eventually mothers decide they’ve trampled enough, they grab the alien, put it in the trash bag and throw it in the dumpster[19].

Block 6. Rising action. Living in a trash dump (hide and seek among the dumpsters)

The alien suffocates in the piles of trash, that grow bigger and bigger. Hunger made the extraterrestrial traveler extremely weak, and it is forced to consume some shreds of fabric it finds from time to time in the rubbish. If it fails to get out of the dumpster, it will suffocate or choke on the slurry. There are two ways out: the alien can climb out by its own, or a hobo can fish it out and carry it with the rest of the scrap to the car sheds. One way or another, the tourist ends up near the car sheds, unless it chooses to try the highway, the sandbox or the football ground again.

Block 7. Climax. Car sheds, hooligans and desperation (beyond the edge of life)

At the back of the car sheds, hobos jangle and fight over their possessions[20]. The local hooligans arrive and scatter the hobos away, to start their own rumble. They grab the alien and use it as a mouth gag. Fear of the victim slows the creature down, to make things worse, saliva causes alien’s body to fall apart, choking the victim, who is now utterly terrified of inevitable death. This terror affects the creature to the extreme, leaving our hero practically paralyzed and lifeless.

Block 8. Denouement. Ambiguous ending (hibernation of hope).

The half-dead tourist awaits some help from its kin, yet the only advice they can give about such a dangerous and fearful planet, is to find some safe, quiet and dry place to hibernate[21].

The half-dead tourist awaits some help from its kin, yet the only advice they can give about such a dangerous and fearful planet, is to find some safe, quiet and dry place to hibernate – until the emotional ambience of this planet is improved, until there is less fear and violence, until the inhabitants are no longer overwhelmed with fear. Then the teleport can be repaired and the alien can be saved.

Typical elements of the socio-philosophical sci-fi style are barely present here. To fix this, it is necessary to give more attention to socio-philosophical issues within each particular conceptual block to bring them out[22].

[1] Plot is the interrelated sequence of events, conveying the narrative material, which is devised to meet certain requirements of the game. One must not confuse the plot and the script – they both may tell the same story, but there’s a difference in the scale.

[2] Game genres are used to categorize games based on their gameplay interaction and a set of gameplay challenges (platformer, simulation, RTS, etc.)

[3] Checklist is a list of tasks that helps to ensure consistency and completeness in using this method.

[4] see 2.

[5] Literary style may indicate in which manner the story must be written (detective fiction, drama, comedy, slapstick comedy, etc.) or require a visual style of the game – manga, comics, etc.

[6] Setting is the term used to describe the environment where the events of the game take place, a fictional or recreated world (Middle Age England, Magic Dwarf Dungeon, Inside if the Human Body).

[7] Key concept is a short description (20-25 words maximum) of the very essence of the story, it should contain some information about the hero, their goals and obstacles on their way to the goal.

[8] Story arc is a general structure of the plot, which includes the following components: the exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action and denouement.

[9] Conceptual block is a narrative part/fragment that consists of one or more scenes, linked together by a common narrative goal (for example, to introduce hero’s associate to the player, to immerse player into the hero’s character) and achieving it.

[10] Game mechanics – each mechanic is a rule and/or restriction designed for player’s interaction with game elements, which helps the player to achieve game objectives or prevents them from achieving these goals. The game mechanics as such is a construct of rules within which the game operates.

[11] Narrative is linear representation of the event sequence of the game story, conveyed by means appropriate to the media.

[12] Narrative elements are tools, patterns and the overall content by means of which the story and information about the game world is presented to the player.

[13] It is not actually a characteristic feature, rather author’s association.

[14] You do not necessarily have to use all of the elements for the conceptual blocks, if some of them don’t work for your story, just leave them out or use them as spare ones.

[15] Plot concept was not presented among the input data; however, this idea emerged from different characteristics and associations during step 1.

[16] Here there were some difficulties with forming the storyline, so it was decided to group together characteristic features and associations from the table instead of events, try to combine and rearrange them in order to elicit the best solutions. At this stage, conceptual blocks are very vague and sketchy.

[17] After trying out different order of conceptual block, we choose the most promising storyline. It was decided to devote five blocks (which is considerably many) to rising action.

[18] There we see a scaling error; the description is too detailed and emotional. However, the description below provides a proper example.

[19] Here we see that this block logically contradicts the following conceptual block: it says that the alien can escape, yet the next block begins with the alien finding itself in the dumpster, being thrown there by hysterical mummies. To remove this contradiction, we could mention, that the alien can escape, yet even if it does, its path will lead it through the football ground or the highway, where a youngster or a car will unavoidably bounce it into the dumpster.

[20] It seems that the only reason this element is involved is because it was mentioned earlier as a part of this block. It is redundant here, so we can excluded it freely.

[21] Lack of cause-and-effect linkage – it is not clear from the story why exactly they give such advice. The better option is presented below.

[22] This is a serious flaw of the story.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like