There isn’t much in Moon Hunters’ mechanics or its emphasis on replayability that’s strictly new; what impresses is how they are used to draw the game’s theme into sharp definition.

for my

“We remember something new with each telling. Together, let’s tell the story again and again.”

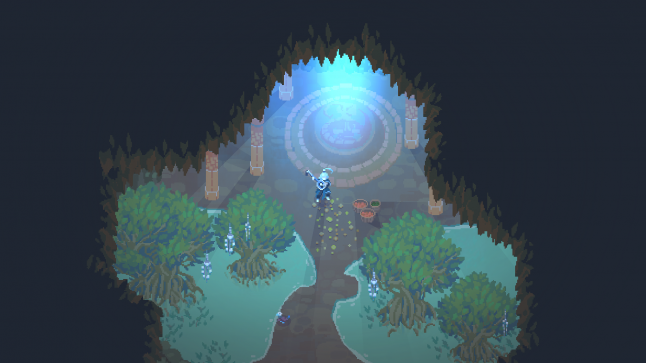

With those words begins another session of Kitfox Games’ Moon Hunters, a puzzle-box myth that was recently selected as one of the PAX 10. Each playthrough is a variation on the theme of an epochal event that sees moon-worshipping tribes pitted against an ascendant, militaristic sun cult bent on destroying them. A single session in this game--once billed as a “co-op personality test” for its heavy emphasis on taking the measure of your character--will last between 75 and 90 minutes, but it’s not meant to be played once.

This is, more than most RPGs, a truly mythopoeic game from top to bottom. It is about playing through every possible embellished variation on the same mythic story, a ludic rendering of how our own real myths come to be. In this, the repetition serves an expressive purpose. There isn’t much in Moon Hunters’ mechanics or its emphasis on replayability that’s strictly new; what impresses is how they are used to draw the game’s theme into sharp definition. Moon Hunters is a prime example of a game that harmonizes its themes with its “gamey-ness.”

Another useful example of this can be found in Subaltern Games’ No Pineapple Left Behind, an excellent and darkly amusing charter school simulator. Often, hyper rationalized sim mechanics, where everything has to be reduced to a measurable set of inputs that deaden any realistic portrayal of society, are something that have to be fought against by developers even as they need to employ them. Pineapple, however, benefits from all the ruthless scorekeeping in order to make its point about the soulless nature of for-profit schooling. The point is to create an environment where numbers trump the messiness of human individuality, and thus classic sim quantification becomes core to expressing the game’s ideas.

You hire and fire teachers on a whim, while drilling students to maximize standardized test scores; all revolves around turning a profit at the end of the day and running the numbers. For many other games, this would require a simple suspension of disbelief in order for it to achieve a certain verisimilitude; Pineapple makes you dwell in the literalization of the game mechanics, using them to make a point. Whether you agree with that point is less important than the game’s success at wedding its theme to a mechanic; the fit is very much hand-in-glove.

Moon Hunters’ replayability and achievement-hunting work in the same way. You’re less simulating the One True Quest to Save the World than all the tall tales that follow it. Such stories feature a rotating cast of heroes, with different exploits and fatal flaws. Around a thousand campfires such stories bloom, and you can play through as many as you wish. That this co-op game makes for collaborative storytelling is all the more appropriate, mythmaking being a collective rather than a solitary enterprise.

There is a curious persistence in the game world that gives it an eerie, time-lost feeling. If you play again after beating the game, your previous hero’s name and deeds will be referenced and even memorialized in the world--despite you theoretically replaying those same events at the same time. Other traits, like learning to talk to animals or spirits, persist through all subsequent playthroughs once unlocked. It all suggests that in the retelling of the story it becomes both more refined and intricate. Once again, such unlocks are nothing new, but the narrative role they play here is unique. They become notes in future bardsongs of your composition.

For my part, at least, I wanted to play again and again, seeing what I’d missed, piecing together a growing body of clues to figure out how to get the “best” ending and add more constellations to my star chart--I wanted to keep telling the story. The story also tells you something, of course--your moral choices add up to a literal constellation in the heavens that reflects and memorializes your personality, though it’s not quite a personality test in the way Kitfox once advertised. The game urges experimentation and, after a fashion, you’re weaving new mythological characters rather than a reflection of yourself per se.

All of that can get hazier still in the midst of frenetic co-op play; enemies come fast and thick, demanding twitchy responses that the controls mercifully cater to, with each class having a unified crowd-control/panic button that ensures even strategically-minded play becomes second nature in short order.

The lavish in-game art certainly doesn’t hurt either, adding brilliant detail to the pixelated universe, as well as an elegant flourish upon Tanya Short’s writing and character design. You can play as a member of one of four tribes, each with its own distinctive culture, built around worshipping a different aspect of the Moon Goddess.

As time goes on, you get the feeling that reliving these five fateful days and their variations are the result of a messy collaboration between them. The game takes its cues from a variety of real myths, all with the Tolkienesque implication that you are playing through the origin story of our very own world. Gilgamesh and Baba Yaga appear, with a number of cues borrowed from both Celtic and Near Eastern myths, and a none-too-subtle correspondence with the rise of monotheism in the Levant. It’s a Riane Eisler book come to life with none of the dodgy scholarship, just the purity of storytelling in the forgiving voice of a songstress.

The tales run together, and the achievements for unlocking new characters or areas embrace this. You don’t “discover” the High Tribes, you “remember” the people of the mountains. Each telling jogs new memories, making the tale all the more intricate. You can imagine future generations of children arguing with each other about the stories. “Nuh uh, Kubele would never marry King Mardokh! She stomped him into the ground!” “Well, I heard she tried to steal one of Idunn’s magic apples.” “You’re both wrong, she crossed the Bridge of Heaven before carving her wish into the World Tree.” And I can just imagine a clan’s indulgent Lorekeeper smiling as she says, “perhaps you’re all right.”

***

“The heroes are different every time, the world changes every time; journeys end, but stories live on,” the prologue gently intones, framing the game more literally than you may first expect upon diving in. Rarely is a game’s story so indistinguishable from its mechanical conceit. In Moon Hunter’s excellent art book--a shockingly useful text that is a paragon of its otherwise superfluous genre--Short writes in the character of a future archeologist:

“Issaria was on the cusp of being forgotten forever; we have dredged it from the bottom of our consciousness, but the essence is not a brittle, solid thing. It lives in our minds as a story, ready to be retold, with each piece able to be moved and readjusted to suit the purposes of the teller.”

It’s a beautiful way of justifying the randomly generated map of Issaria you confront in each new game, and it’s a testament to Moon Hunters that it has lived up to this spare, clever sketch.

“Replay value” takes on an entirely new meaning here; you replay what is valuable in Moon Hunters. Not perfectly, of course--subsequent playthroughs can sag a bit; despite the procedurally generated world, running around gets old fast. But it never drags on, keeping you moving from beat to beat in each retelling of this enchanting story. Fast enough to make you want to do it all over again until you know the name of every star in the sky.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like