For francophone audiences, Benoit Sokal was known as a comics arts before he designed the Syberia franchise. He says the transition into game design was a natural extension of his skills and talents.

For nearly two decades, Benoit Sokal has been a peerless impresario of point-and-click adventure games, most famously for the longrunning Syberia series which is now, at long last, releasing its much-anticipated third installment. But, particularly for Francophone audiences, Sokal was known long before his game design days as a colorful cartoonist from a golden age of comic art, flowing from the pens of many French and Belgian artists--particularly for his satirical Inspector Canardo, which follows the many adventures of a sauced duck detective in an anthropomorphized send up of noir detective drama.

For Sokal, the transition into game design was a natural extension of his skills and talents as a comic artist, and it also put him in a unique position as the creative lead for his games.

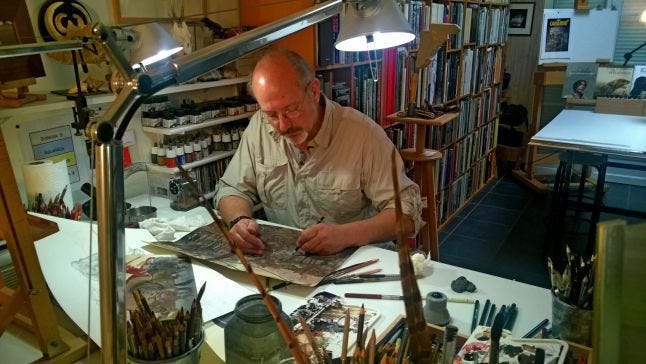

Sokal is a fascinating figure in game design because his vision is one he was actually able to paint with unparalleled skill. You were looking at his clear, unfiltered vision when you played his games. He drew the concepts and shaped the game’s visual language without mediation. To play is to get a sense of the inside of Sokal’s head in a way few videogame auteurs are capable of allowing.

I spoke to him recently about his transition into game development, as well as a few odds and ends about the development of Syberia 3. He also hints at a fourth installment for the series where Kate Walker’s adventures come to include romance.

You've worked as a graphic novelist and cartoonist since the 1970s, and were a contemporary of some other well known Belgian cartoonists in a country renowned for its comic tradition; how did you go from Inspector Canardo to making videogames?

I was quite naturally going back and forth from one to the other following the development of technology which allowed me first to colorize my comic strips with the help of a computer and to rather laboriously create small drawings with a mouse. Soon, I was interested in 3D computer generated images. By watching movies like Jurassic Park or Titanic, I had a kind of love at first sight for this technology that made it possible to render "hyper-realistically" things directly coming from the imagination of its creator or things that had totally disappeared.

I offered to my comic book publisher to produce, with these new types of images, a short story: what was called at the time "an interactive CD-ROM." I got caught up, the beginning of my ambition grew further and with a very small team, we worked during four years to develop “L'Amerzone.” For me, it was only the natural evolution of my trade: that of storytelling but only the tools changed.

Looking at Canardo there's obviously a darkly humorous sensibility about it--an alcoholic duck detective who hates his job but keeps solving mysteries in a strange anthropomorphic world. But with Syberia you moved into a kind of supernatural fantasy that was less cynical and more hopeful at its core. Crucially, you went from a protagonist who was a comically lecherous male to ones who were genuinely strong, serious women in both Syberia and Paradise. What inspired you to move in that direction?

I created Canardo at a very young age, I was 23. At the time, I was reading a lot of detective novels. Canardo was a parody of this genre; I probably had some significant teenage concerns and a dark humor to go with it. But I was afraid to find myself prisoner of this character’s success and not be able to address other themes and other kinds of stories. I always had the concern to diversify myself. Kate Walker was imagined more than twenty years later after that time. I had just simply changed and evolved. I guess I was looking at life differently!

Oftentimes in the videogame world, artists are seen as important but secondary players, painting someone else's vision for a game. But as the artist for Syberia it really is your world and your vision, you draw something and get to make it into a videogame. What overlap do you see in your work as a comic artist and a game designer? What skills do you bring from one profession to the other that you think others could learn from?

I never imagined playing video games as a medium of expression in its own right. I consider myself as a video game author as one could be novelist or film director or cartoonist.

If, of course, the writing is very different, it nevertheless remains that I continue in video game to do what I have always done: create imaginary worlds; set a scene with great care and tell visual stories.

Yet, between the two genres, there are nonetheless immutable dramaturgical rules: how do you take the reader or player by the hand and guide him into the universe that is offered to him ... How do you create empathy between him and the characters we imagine.

And above all, to intrigue, confuse, and make him laugh or to cry: in short to create emotion.

But all that only works if you stay true to yourself. Only if one is going to seek his inspiring raw material deep inside, in what one has most secret and more intimate, hoping that in spite of all it interests the greatest number.

When we spoke about Syberia 3 at GDC, you vaguely alluded to something about questions about Kate Walker's sexuality. Could you expand on that?

All stories are love stories. So I do not imagine that the adventures of Kate Walker could never benefit from a romantic engine as powerful as love and sexuality. I am currently creating for Kate Walker a love story that will take place in Syberia 4. What will be her ups and downs? The directions she will be taking? it's probably a bit early to say. But Kate Walker is an intelligent and free woman: her motto is “Adventure!”, which is included in her love choices... I can only imagine that these will never be final or stopped.

.jpg/?width=646&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The Youkols obviously take a lot of inspiration from Arctic native tribes. What efforts were taken to avoid stereotyping or racist imagery? Were any actual northern natives consulted for the project or was research done?

I have been very interested in the cultures and religions of nomadic Arctic peoples such as the Nenets of Siberia and the Tsaatans of Mongolia. I read a lot about their trances and paths to get there, and I met with shamanism specialists like Corinne Sombrun. The beliefs of these native peoples have hardly changed until the last few decades. They are fascinating because they use notions lost to the modern world: the permeability of the boundaries between the world of the living and the spirits and the fluidity of time passing ... Years, centuries do not exist for our ancestors, those who drew dancing animals on the walls of the caves.

*Editorial Note: This interview was translated from the original French by Daniel Sarrazin.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like