Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

A hands-on guide on how to start out in the design of an engaging and dynamic game system. The post offers an insight into the narrative and cognitive forces behind the concept of control and pacing, helping designers to organize and direct thoughts.

“Putting into play” originates from the site Narrative Construction, and is part of a project whose goal is to offer a hands-on approach to the design of an engaging and dynamic game system from a narrative and cognitive perspective. The series illuminates how our thinking, learning, and emotions interplay when the designer proceeds from scratch to reach the desired goal of a meaningful and motivating experience.

Before initiating the hands-on process of organizing thoughts and feelings at the start of the design process, I will explain the dynamic forces behind your prime tool as a narrative constructor. The tool is more of an advantage derived from the rapid pace by how our mind is processing information that you employ in the same manner as a magician engages the receiver's perception, attention, and awareness.

Your opportunity to engage the receiver’s sense- and meaning making can be found in the drive behind our desire to understand. The dynamic forces behind this drive are so strong that we even sacrifice logic in favor to retain or retrieve the satisfying feeling of understanding. I refer to these forces as the motivating engine of learning that invites you to control the pacing of engagement through the blocking and triggering of the receivers' meaning making.

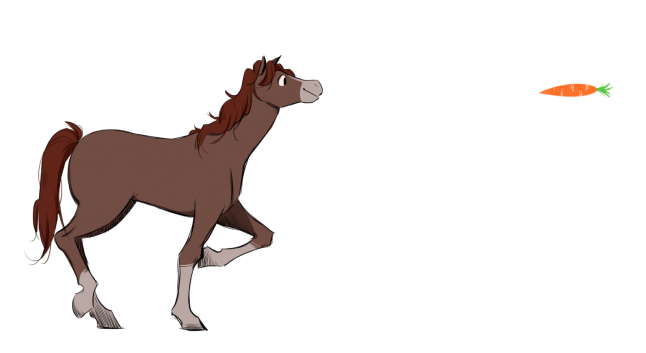

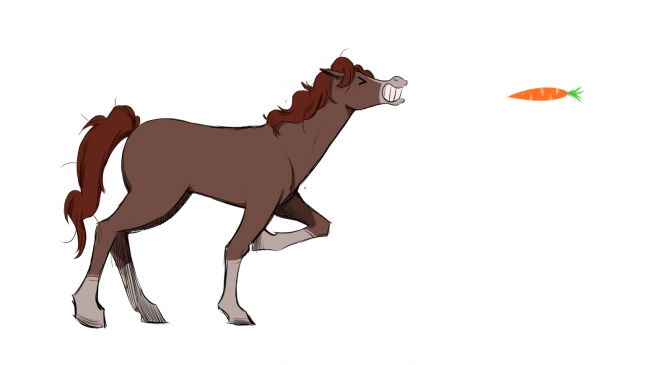

To access the motivating engine of learning and how you control the pacing of the receivers' engagement, I would like to describe the dynamic forces using a horse, and where our innate desire to understand (learn) functions as a carrot.

By presenting the carrot before the horse’s senses (touch, hearing, sight, taste, smell) you are triggering the desire to reach the carrot which motivates the horse to move towards the carrot.

To avoid making the horse lose control by not letting it get the carrot...

… you are carrying several carrots in your pocket that you arrange in a manner, so the horse’s motivation to retain or retrieve composure from the feeling of control is maintained (balanced).

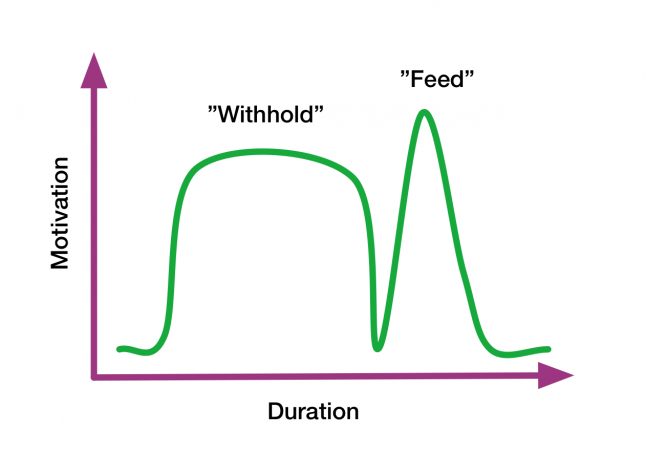

By alternating between feeding and withholding the carrots, you control the duration by tuning and balance the grades of engagement (intensity) and its effects on the emotions and motivation.

In everyday language, we call the narrative techniques employed when triggering and blocking the receiver’s meaning making surprise, suspense, and foreshadowing.

The techniques and their effects are commonly associated with theories explained by the ancestors of the media. Still, in the design of engaging and dynamic game experiences, there is much more to be explored within these narrative techniques. Above all, it is the sense of touch added to sight and hearing and the perception to “interpret” the data from the senses that requires rethinking the possibilities of the narrative as a cognitive process.

To access the unseen activities of emotions and thoughts which you are targeting when arranging (composing, tuning and balancing) the pace of your narrative with the help of a “carrot”, try replacing the “horse” with the following description of how our mind is processing information:

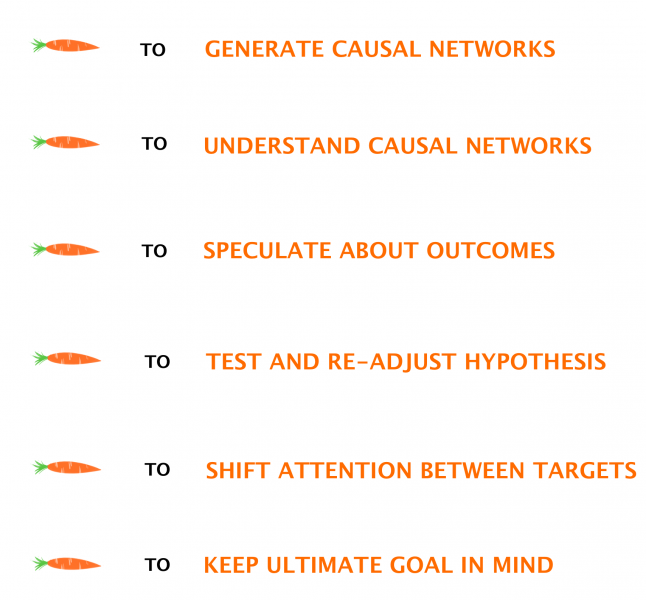

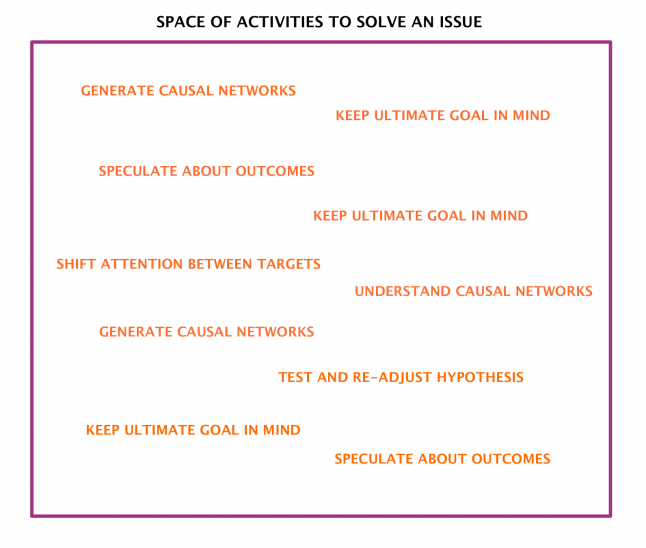

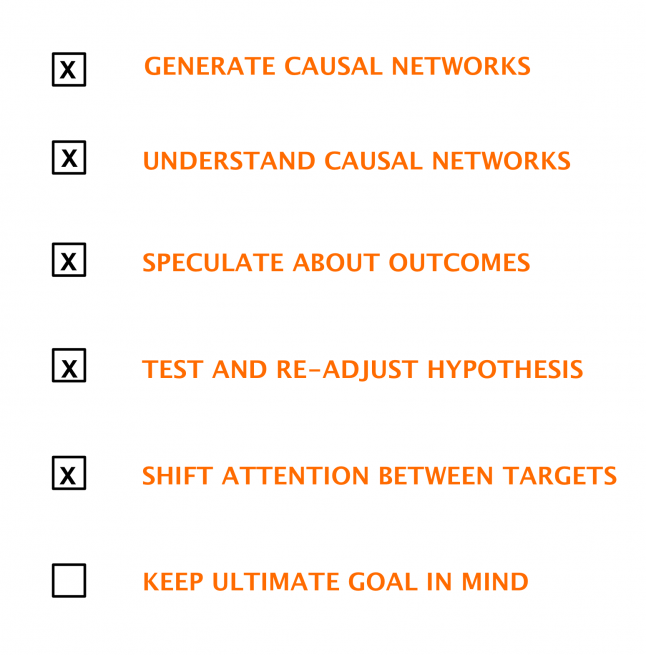

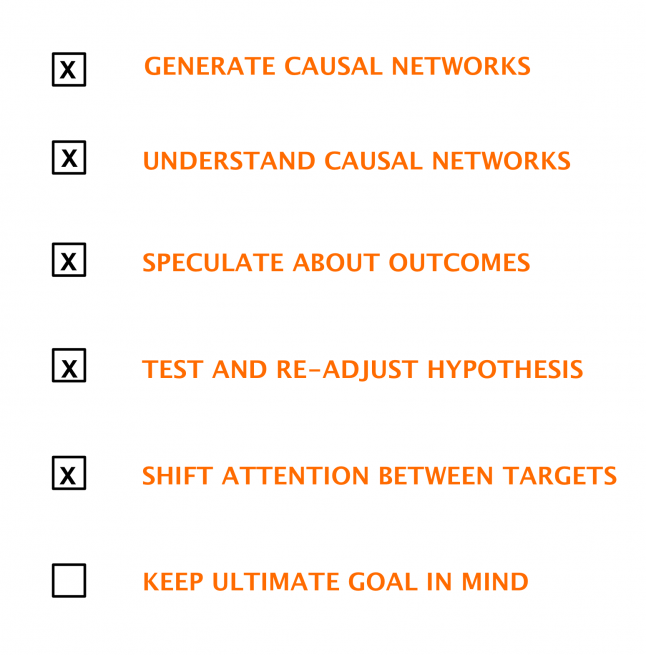

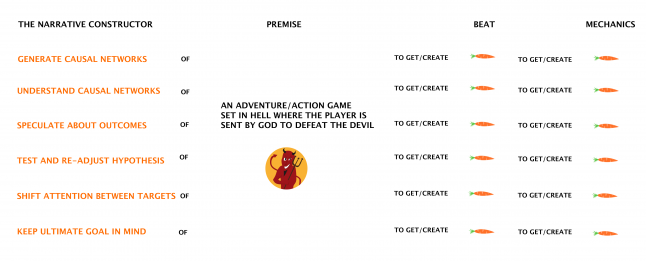

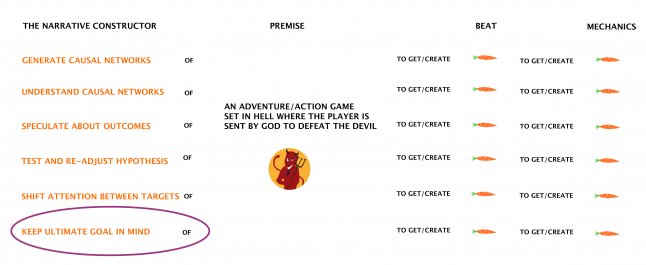

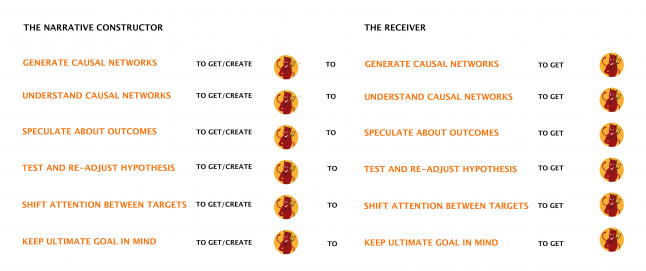

"The ability to generate inter-domain causal networks, use network understanding to speculate about potential outcomes, test and re-adjust our imaginative hypotheses, and to shift attention from one target to another, while keeping in mind the ultimate goal (e.g., subsistence) over an extended period is unique to the human mind of today."

Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017

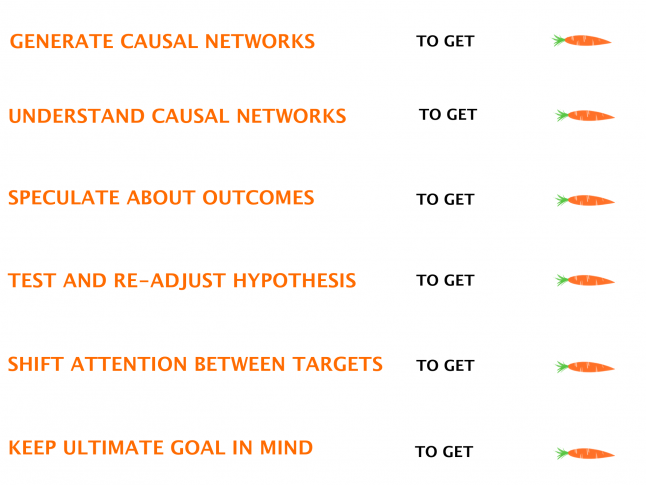

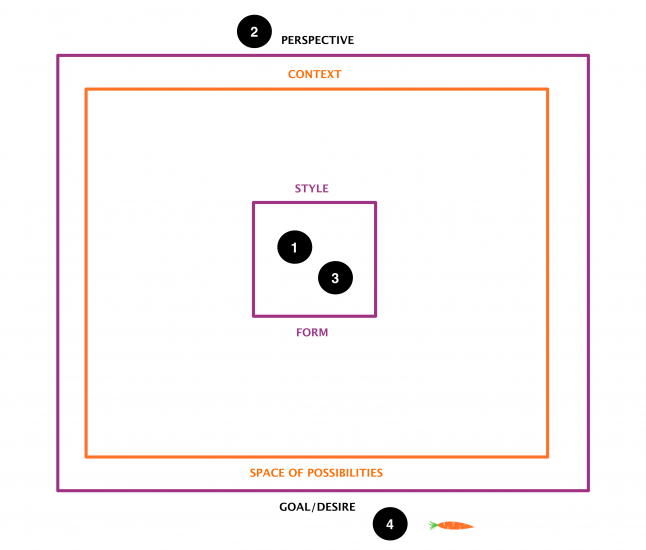

As explained by Gärdenfors and Lombard above, our core cognitive activities can be broken into components, thus illuminating how the “carrots” constitute the parts that will be reflected later with the help of stylistic elements of sound, graphics, effects, levels, interface, control devices, physics, systems, mechanics, etc.

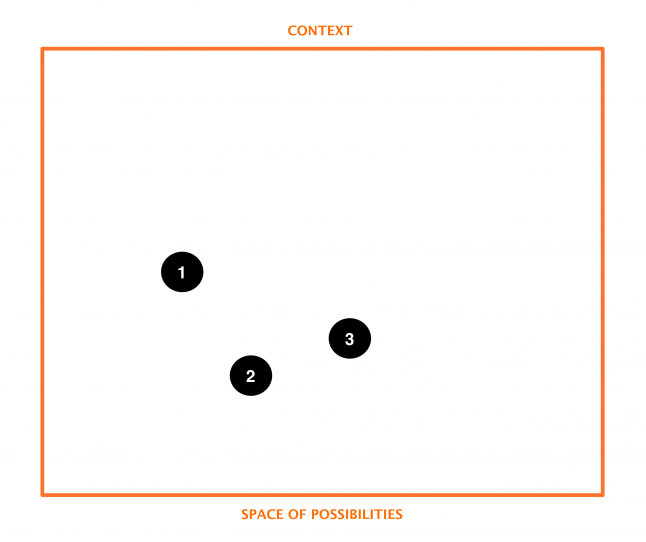

You can look at each cognitive component separately to get an idea of how the parts contribute to the building of a narrative and cognitive core to a system that activates the motivating engine of learning. The diagram below illustrates how each “carrot” contributes to your intention of what you would like the receiver to do on a cognitive level.

How you can recognize the dynamic forces from the motivating engine of learning, I will give an example from the other day when I gave in to the desire to solve a crossword by using Google. If you recognize the experience of

- looking up an answer that you are supposed to figure out by yourself (as I did) or

- unlocking something in a game that (from what you know) isn’t supposed to be available

…then you have also experienced how the dynamic forces of the motivating engine of learning are translated into actions that reflect how our core cognitive activities are processing information.

Whether you are playing a game or solving a crossword puzzle, the activities generated from the forces actually invite the building of a blueprint for a dynamic space. This can be of help if you haven’t yet found a place for the stylistic elements to convey the experiences and feelings into a form.

The diagram below can be used to imagine any context where the components of the core cognitive activities are applied. It illustrates how actions are evoked, whether you are solving a crossword puzzle or feeding a gigantic ancient creature in a video game:

Back to the crossword which didn’t only engage my cognitive activities but others as well, who discussed if using Google was the right way to solve a crossword puzzle. Obviously, we have agreed on meanings that imprint our every day with rules and behaviors. These activities, in reality, share the same narrative and cognitive forces that a narrative constructor employs in the creation of an engaging and dynamic space in fiction. This is why I suggested earlier that you need to become your own narrative constructor to enhance the capacity to discern cognitive and narrative forces in reality.

Presumably, we all recognize the discussions about the “do’s and don’ts” and the expectations enforced from others and ourselves. However, the essential part of your prime tool as a narrative constructor is recognizing the narrative and cognitive forces behind the desire to understand as a possibility. For example: if a player finds an alternative way that you haven’t considered as a possibility in your design of a space. Instead of feeling that you did something wrong, give yourself a pat on the back for triggering the players’ exploratory curiosity.

The possibilities provided by the motivating engine of learning allow you to utilize the dynamic forces behind the feeling of “doing something that you aren’t supposed to do” to increase the emotional experience. For example, if you ever entered a space in a game that appeared forbidden or made you feel exclusive, as though no one else but you could have found this place, it was most likely the design of a narrative constructor who had explored the possibilities of this particular space.

Another example with less emotional impact compared to the feeling of exclusiveness is the Easter egg. Under specific circumstances, the Easter egg is an expected element, which means that if there aren't any in a particular place, a surprise is created from the fact that something expected didn’t happen. When comparing the forces behind the two effects of a surprise, you get an idea of how the emotional effects and their duration can be graded. The longer you engage the receiver's meaning making, the stronger the emotional impact of the experience, which could even linger in memory for the rest of the player’s life. The shorter the exposure, the greater the likelihood of an experience being stored at the back of our minds, making us believe it was unimportant enough to be forgotten - until the moment that we are exposed to the experience/feeling again. Depending on what you want the receiver to experience or feel, by handling the causal, spatial and temporal links you are timing the "right moment" to remind the player. If handled well, the result will be considered a spoiler if it's mentioned before others have experienced it.

How to utilize causal, spatial and temporal links to create effects by arranging the “carrots" are details that I will return to later in the series. Right now, before moving on to the hands-on part, I would like to emphasize the importance of recognizing the narrative and cognitive forces behind the prime tool in the control of motivation and pacing of engagement.

Knowing that it can feel a bit strange to see what we usually do in a millisecond depicted using the bullet-time effect, I recommend reading the previous chapter to get an insight into how our causal thinking and understanding work (see links below). As I advocate a cognitive approach to the narrative in the building of engaging and dynamic game experience, it is thanks to the game designer Fumito Ueda's transparency when sharing his thoughts on the design I have been able to introduce the 7-grades model of reasoning (Gärdenfors, Lombard, 2017).

In particular, it is the higher grades of the 7-grades model you employ as a narrative constructor to which you add the narrative keys of perspective and position. This allows you to navigate through a space to test and re-adjust the hypothesis to meet the desired goal. Regarding our desire to understand it is depicted in the 4th grade, which shows how we like to speculate about the past, present, and future by putting together pieces of what is presented before our senses. The 6th grade gives you an idea of how to move mechanics, systems, physics, effects, beliefs, feelings and desires of characters to test and re-adjust the outcome (s), which we will get to in the next section.

If you choose to read the links later, I would like to clarify that the term narrative constructor is an umbrella term I use to refer to the joint activity of giving meaning to experiences. No matter what part you are in charge of in the design process the term narrative constructor helps to focus on the narrative and cognitive activities when building an engaging and dynamic game system.

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle

Part 5, Putting into play - On organizing thoughts and feelings

A short guide to the 7-grade model of reasoning

Discern the possibilities

If I were to nominate the core of cores in game development, it would be our thinking. Without it, we wouldn’t have a process, and without a process, we couldn’t build mechanics that meet the activities of our thoughts and feelings.

To create core mechanics that meet the dynamic forces of our core cognitive activities, the behavior, rules, and goal (state) of the mechanics would need to match how we test, re-adjust and shift our attention, which is pretty much what mechanics do. What to discover, though, is how our thinking and feelings from a cognitive and narrative perspective come into play when you are giving meaning to the mechanics.

Based on the simple principle that if you can discern the possibilities, you can also distinguish the constraints I will initiate the process by turning the minds-on activities into hands-on practice. This allows us to recognize what we are doing with the help of the narrative and cognition-based method: Narrative bridging.

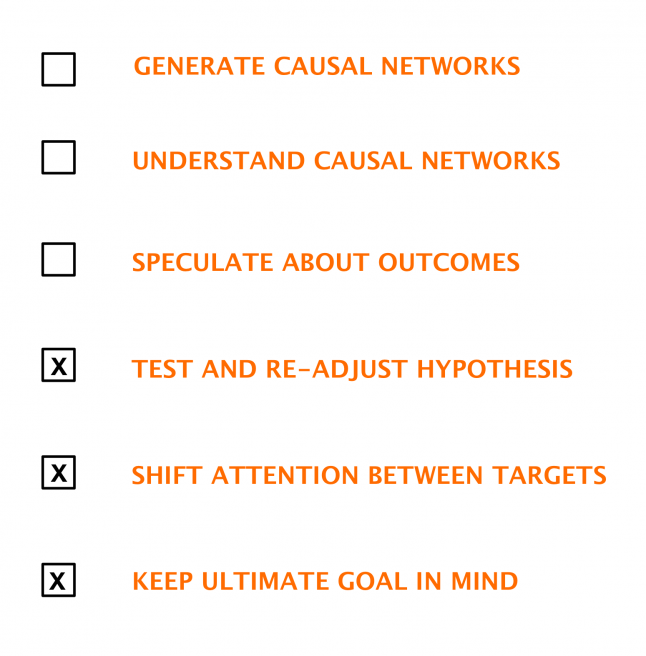

To lower the abstraction level, I will introduce a virtual team that symbolizes our peers in the exploration of the possibilities. Please meet our co-workers whose thoughts we are going to organize in order to start the design process.

Seizing possibilities

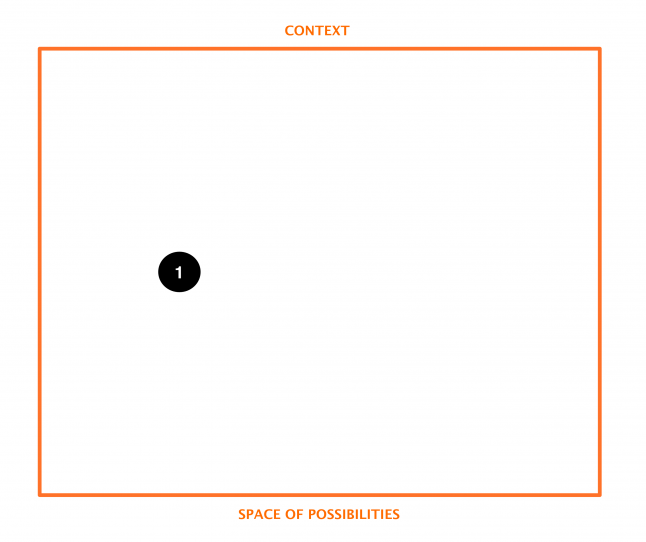

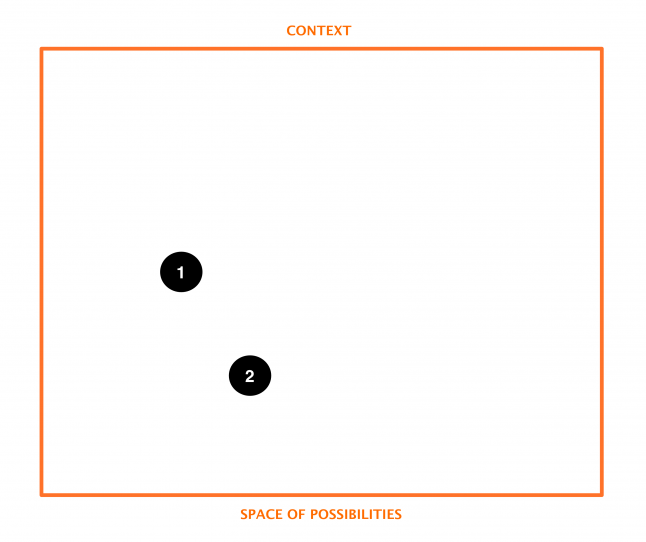

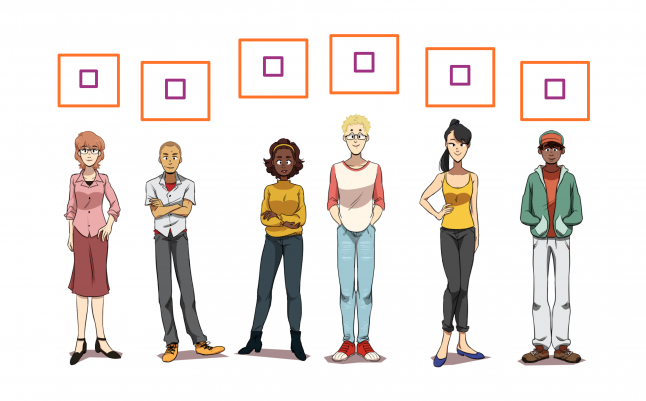

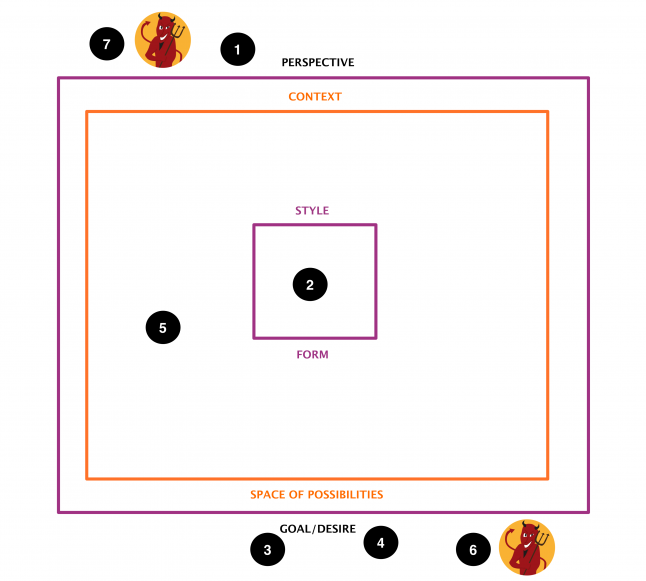

The first thing I will do in the organization of the thoughts of the team is to identify the process of thinking (1) as a possibility.

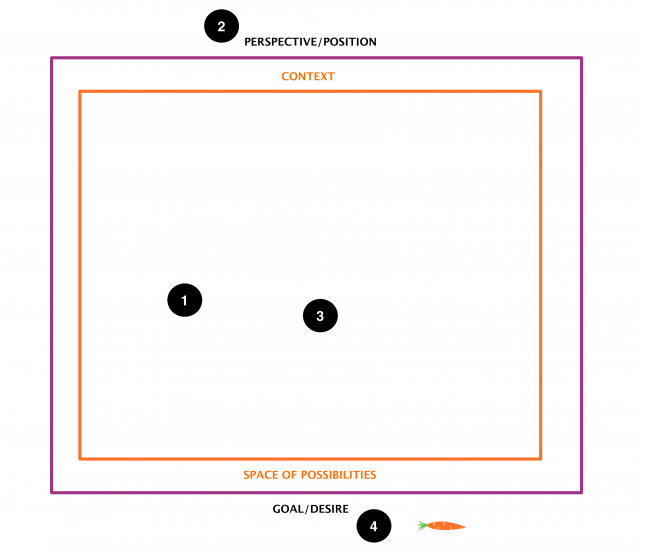

Since the process of thinking (1) proceeds from the medium of our mind, I will add the minds of the team (2) to the Space of Possibilities.

Being at the very start of the design process where the incentive is on organizing the thoughts, we can turn into narrative constructors. With a quick shift of the perspective and position, we can look through the eyes of the team.

Picking up the "carrot-list" from earlier, we can reverse the components of the core cognitive activities and look at them from the team's (2) point of view. What we need to do to put the process of thinking (1) into play is to perform the activities below to "get the carrots." It means that we need to understand the parts that are to take form.

Since the cognitive activities (above) give the process of thinking (1) a form, I will add components of the core cognitive activities (3) to the Space of Possibilities.

Perspective and position

From having focused in the series on showing how our causal thinking and understanding work, I will pay attention to the narrative keys of taking perspective, which we just did when looking through the eyes of the team (2) from the position of being narrative constructors.

Since the perspective is an established term we use when looking at something from different points of view, the position is what helps you navigate when moving dynamic forces in the space of a game world. By making the main perspective and the position to be from the narrative constructor’s view, you can move through the space of causal, spatial and temporal links without losing track of the direction.

For example, if I were to move the character Lucifer according to the 6th grade, i.e. the devil from a television series that I introduced in the previous chapter, I have mind-wise navigated and maneuvered the narrative and cognitive forces of Lucifer through space as to test and re-adjust hypothesis in a new context.

In the example of Lucifer, you can see how the narrative keys also have a generating function as each new perspective and position you take unfolds new experiences. This is what happened when I made Lucifer a part of the team in the previous chapter.

The techniques carried by the narrative keys are depicted by the following components of activities:

The goal

To clarify, this is the point at which the narrative key of an ultimate goal comes into play and directs our core cognitive activities.

Thus our thinking is not a step-by-step activity, but a causal process where thoughts and feelings intertwine simultaneously; it is hard to tell which comes first, the perspective or the goal. The goal helps you to direct and control the cognitive activities of shifting attention between targets to test and re-adjust hypothesis while changing positions to take new perspectives. In your daily practice as a narrative constructor, you can recognize the cognitive activities from the questions of who? what? when? where? how? and why? in relation to addressing the goal.

The premise as a blueprint

The core cognitive activities and the narrative keys are also what constitutes the system of the minimum data of a premise, which works as a blueprint to the elements that trigger the narrative vehicle of meaning making (see Part 4 where the premise was introduced).

An identified subject(s) and a condition(s) that propels a process forward in relation to what the receiver should experience or feel.

With the help of the premise, we can return to the team (2) and take a look at what we have explored so far in the Context and Space of Possibilities:

We have identified the team (2) to be the subject and the predicate for the condition, which propels the process of thinking (1), and the core cognitive activities (3).

To evolve the premise, I will continue the organization and direction of the thoughts and feelings and add the perspective, position, and goal (desire).

By taking perspective and position as narrative constructors (2), we can identify the desired (ultimate) goal (4) to be on learning as to understand (which result of understanding is so far represented by a carrot but will gradually take form while we go).

If we return to the blueprint of the premise, we can now add the narrative key of a goal (4):

We have identified the team (2) to be the subject and the predicate for the condition, which propels the process of thinking (1), and the core cognitive activities (3) to reach the experience of understanding (4).

To put the process into play towards the desired goal (4) I will make a last move into the Space of Possibilities as to identify, from the process of thinking (1) and the core cognitive activities (3), the Style and Form of the medium of minds - the team (2).

Style and Form

Referred to the Style and Form in Narrative bridging is the possibility to define the media and its specific attributes.

Since the medium is the minds of the team, the core cognitive activities (3) give the process of thinking (1) a behavior, rules and a goal, which results is derived from the desired goal of understanding (4).

To see how the media-specific attributes convey a form of a system, I will organize the last pieces (3 and 1).

Giving the medium of the team’s minds (2) a Style by proceeding from the core of how our thinking is processing information (1) and where our core cognitive activities (3) provide a Form, we can identify a core to the process in the form of mechanics to explore (1 and 3).

An engine of learning

The result of the organization of the possibilities is a mindset to explore the possibilities. Based on the concept of learning (presented in the previous part) that is built on the belief in our capacity to think/learn and the mindset of being curious, we have created a system to an engine of learning.

As the goal of the mechanics of exploration (1 and 3) is to take care of the results from the desired goal of understanding (4) which generates carrots at the moment that are to take form later, the mechanics meets following activities:

To motivate the engine of learning to generate new experiences, I will equip the team with the mindset of being curious and the mechanics of exploration, which can take care of the outcomes from the generation, speculation, and understanding of space.

To test the mindset I will initiate a new session to see how the results from the mechanics of exploration can discern the possibilities and constraints.

To assist the testing I will invite Lucifer to join the team.

Testing the mindset of curiosity (learning)

In the previous chapter, I used the devil from the television series Lucifer as an example of how our beliefs and desires influence the process by assuming Lucifer made a game and where he shared his beliefs on sex, drugs, and punishment and that everyone in the team held the same desire. Seen from the 6th grade of causal thinking and understanding (see Part 1), by imagining Lucifer from different perspectives and positions, we have carried out a movement of the narrative and cognitive forces of a character.

To test the mindset, I will set up a new frame with the help of Narrative bridging onto which we are not only moving the dynamic forces of Lucifer but also the mechanics of exploration.

I will also add a new element to the desired goal in order to let the possibilities of a game unfold from the core to how our thinking works, using the narrative keys as additional help.

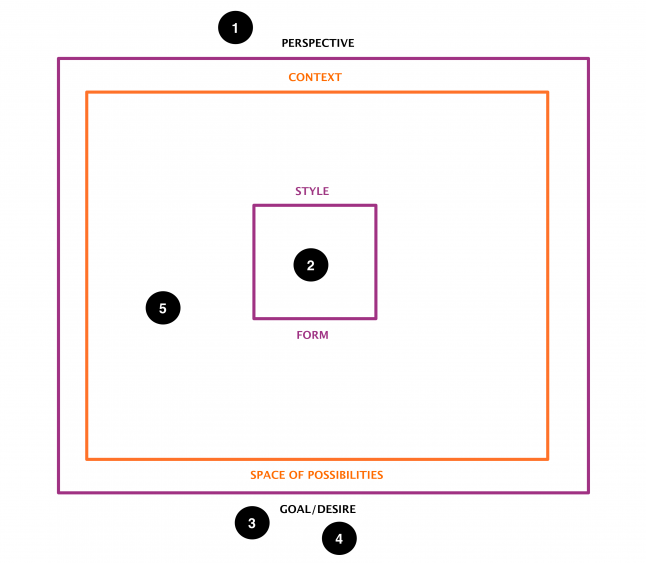

Note that the numbers from the previous iteration will be changed as we start a new phase.

The new frame above shows the perspective of the team (1) and the mechanics of exploration (2) that produces results from the desired goal of understanding (3). To motivate the engine of learning to explore and generate new experiences, I have expanded the desired goal to target the process of making an engaging and dynamic game experience (4) in order to make the space of possibilities of a game (5) unfold.

To unite the minds of the team (1) so as to target the same goal (3 and 4), I will present three coherent scenarios that show how reciprocity regarding a shared goal matters to the design of an engaging and dynamic experience. The first scenario displays how constraints from beliefs could call upon our attention but also have a blocking effect on the process. But if you can prevent the constraints from the first scenario, the second scenario reveals the specific bond that will unite, not only the team but also the team's and the players' minds. The final scenario will show how you can turn constraints into possibilities by staying close to how our thoughts and feelings work.

Any resemblance between Lucifer and persons, in reality, is purely coincidental.

Scenario 1 - Discern constraints of beliefs, meanings, and preconceptions

Reciprocity from a narrative constructor’s perspective is not based on shared beliefs but gained from the shared exploration and learning (2 and 3). This means that if we set the reciprocity on learning in the initial phase, we can detect constraints of beliefs, meanings, and preconceptions that could have a blocking effect on the process.

Let’s say Lucifer draws our attention to his beliefs on humanity, which could easily start a debate. By holding on to the perspective and position of the team (1) whose thoughts are processing through the mechanics of exploration (2) that are directed at the desired goal to understand (3), this is how the activity of paying attention is depicted through Narrative bridging:

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The image above depicts how the team’s (1) senses are triggered by the stimuli of Lucifer and how they process the information (2) in order to understand (3) how to make the game (5) unfold in an engaging and dynamic manner (4).

Though the beliefs we hold are part of our ability to imagine, we don't have to bother about Lucifer's or others’ beliefs if everyone is willing to take on the mindset of learning to explore the game (5). In this way, our beliefs and experiences can become a possibility and the sharing of beliefs and experiences is part of the communication between peers, which is in line with the desired goal to understand (3) how to make the game (5) unfold engagingly and dynamically (4).

A constraint to the process would be if the assumption that sharing a goal is equal to having the same beliefs and sense of meaning, and that the need for control in the process easily gathers people of the same beliefs (see part 5). The cognitive and narrative pitfall here is the unconscious building of a group that maintains and repeats familiar structures of beliefs and conceptions. Whether we manage to discern the cognitive constraints from a belief-oriented approach to the design process depends on how, or if, we react, and if we will reject or embrace the unfamiliar.

If something unexpected happens that unsettles the group, you would probably regret putting Lucifer on the team and consider removing either him or yourself.

The attention created could easily turn into an engagement of having our beliefs about Lucifer occupying our thoughts and feelings. The mechanics of exploration (2) will indicate a constraint from the distraction to the desired goal (3 and 4) caused by preconceptions as one result (Lucifer) keeps repeating itself which blocks the process. Whether Lucifer will turn into a cognitive pitfall depends on the intensity and duration of engagement, which could even affect the motivation to reach the goal. As engagement doesn’t necessarily mean positive progress it could lower the motivating engine of learning.

In a real-life situation, there would be an obvious need for team management to refocus on the shared mindset of learning and curiosity so that the constraint can be removed before motivation drops. Since conflicts engage in reality as well as fiction, what could actually become a problem is if the removal of a constraint was based on beliefs.

The tricky thing at this point is how you differentiate between the feeling of retaining composure from removing a constraint, and the temporary feeling of relief from getting rid of a problem in order to maintain beliefs and preconceptions, i.e. having Lucifer removed from the team. The important thing is knowing what constitutes the constraint, as it could just as well turn into a possibility. For example, who knows how Lucifer could contribute to making the team reach the desired goal?

Scenario 2 - Uniting minds towards a reciprocally shared goal

I have explained earlier how a bond is formed between the narrative constructor and the receiver in the creation of engagement using descriptions by filmmaker Andrew Stanton and game designer Hideo Kojima. Both describe the relationship in terms of math, where Stanton says that one should "give the audience 2 plus 2 but not 4" and Kojima stresses the importance of the process itself (see Part 1). The descriptions demonstrate a feeling of trust, which works as a contract of sorts between the narrative constructor and the receiver in the exchange of thoughts and feelings.

If everyone who is involved (1) in the design process takes on the same perspective and position in relation to the goal (3 and 4) to let the mechanics of exploration (2) perform at full capacity, the core to how our thinking/learning works will build a natural bond between the narrative constructors and the receivers/players.

This is the definition of reciprocity, which unites the minds to work towards a shared goal.

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

Basically, the only thing that distinguishes the narrative constructor's cognitive activities from the receiver's is the temporal position, where the narrative constructor is the first to explore the space with the responsibility to set up the possibilities that are to be explored later by the player. The temporal position makes the team (1) into the "keeper of the answer" at the moment when the players put their thoughts and feelings into play.

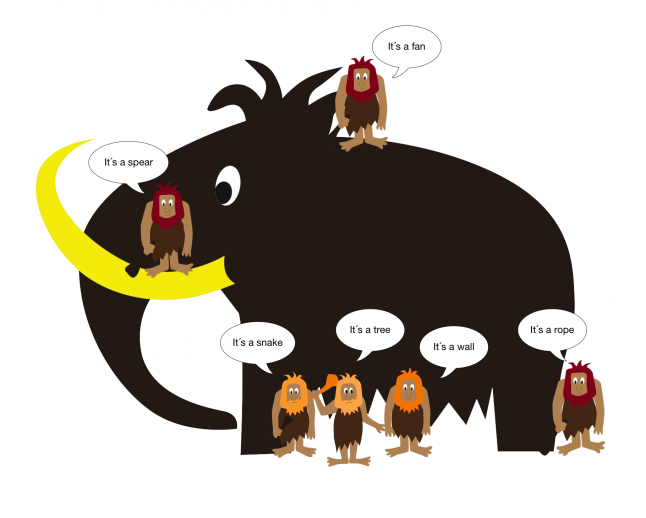

Since the responsibility to explore the space of possibilities of the game (5) lies on the team (1), I will use an Indian fable to describe what it means to proceed from a point when the premise isn’t formulated, and the goal of what the player should experience or feel isn’t settled yet.

The fable is about six blind men and an elephant. The blind men cannot see the big picture (the elephant) but only the parts that are presented before their senses. I have remastered the fable with the help of cavemen and a mammoth to show how the exploration (learning) of a space unites the minds of the team (1), which will create a bond to the players' exploration of the space.

According to the 4th grade, the cavemen are exploring and speculating about the parts that make up the whole, driven by a desire to understand. However, they haven’t yet come to a realization (i.e. understanding). They are also sharing their beliefs and sense of meaning as a natural part of the process of learning. The only threat to the actual process of learning is if they start arguing about whose opinion is the right one, which could extend the duration of the exploration. The show of hands to vote about whose belief to choose also constitutes a threat, as it presents the risk of leaving the mammoth (i.e. space) unexplored.

The cognitive activities of the cavemen can be applied on the team (1) when setting out from scratch to explore the space.

The mindset of being curious and the mechanics of exploration (2) will take care of the outcomes from the generation, speculations, and understandings of the space (5). The team doesn’t have to worry about disputes like the cavemen, who could have left the space unexplored. At least that is how the mindset of learning and the narrative keys are meant to work, which I will let Lucifer challenge.

One of the challenges for the team (1) when setting out to explore the space of the game (5) is that they need to trigger their imagination at the same time as they need to “hold the horse” due to the driving forces behind our desire to understand.

Since the concept of control applies equally to us, the high abstraction level quickly makes us rush the process towards “an answer” in order to “get the carrot.” The combination of the desire to learn and the rapid pace by how we create meaning is what could attract narrative and cognitive pitfalls. It is, therefore, essential to be aware of how the creation of meaning has a reducing effect on the possibility of exploring the full picture in preference to retain or retrieve the satisfying feeling of understanding. In everyday language, we call the reduction categorization, which helps us to store information in memory. Each new element added to the Space of Possibilities will evoke memories since this is how our imagination works. New elements also call forth preconceptions and conventions that may either have a blocking or opening effect on the process. As it is hard to distinguish between what is knowledge, experiences, and beliefs, you leave it to the narrative keys of perspective, position, and the goal to direct the thoughts and feelings, which is also why shared goal pursuit is so important.

However, how the narrative keys can assist you to access the core of the narrative and cognitive forces so as to agree upon a shared goal depends on how you approach the narrative.

To illustrate how you need to stay close to the common denominators of how our thoughts and feelings work, I have used the game The Last Guardian as an example throughout the series. The designer of the game, Fumito Ueda, proceeds from the building of a core based on how our emotions and thoughts intertwine. The interviews with Ueda reveal how there are two approaches within the industry to access the narrative and cognitive forces.

In the first one, you advance from a story structure, which works as a blueprint to access the emotional and dynamic core. In the other one, you proceed from thoughts and feelings and build the structure from this core (see Ueda’s description of this practice in Part 1).

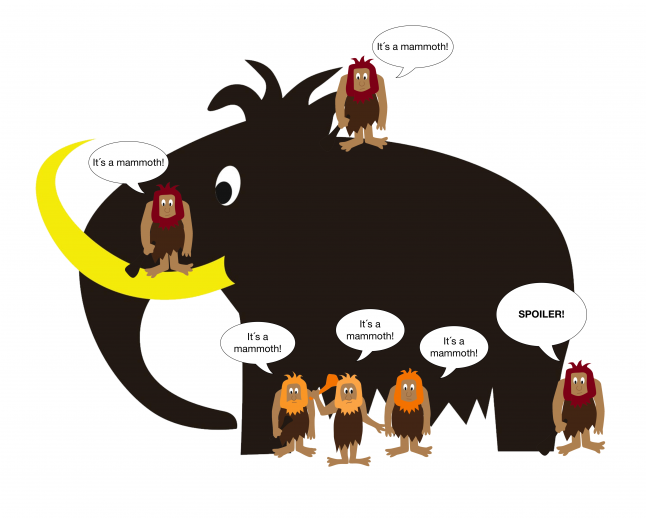

To illuminate the difference between proceeding from a concrete blueprint of a story structure compared to having a rough idea about the goal where the emotions and thoughts are at the centre when building a structure I will return to the cavemen. The cognitive effect on the exploration of space if setting out from a concrete blueprint of a story structure could be as if we gave the cavemen the answer.

Deprived of the fun to explore the mammoth, to "get the answer" doesn't mean an end to the cavemen's exploration of the space. Although the tricky thing is if the cavemen want to re-experience the thoughts and feelings before they learned about the mammoth, they need to summon up curiosity in order to retrieve from the memory the experience of how it was to explore the mammoth when they didn't have the full picture. Due to how our meaning making and memory works, it could draw out beliefs, experiences, and meanings about what could have triggered the exploration in the first place. It is here the mindset of being curious, and the narrative keys and systems of causal, spatial, and temporal links can assist the team in alternating between the core to the thoughts and emotions and the outcome.

If we return to the team to understand what it means to proceed from a concrete blueprint when setting out from scratch, I will let Lucifer suggest the team:

To make an adventure/action game set in hell where the player is sent by God to defeat the devil.

Lucifer’s premise is entirely in line with the minimum data of a premise, which works as a blueprint to trigger the narrative vehicle of meaning making.

An identified subject(s) and a condition(s) that propels a process forward in relation to what the receiver should experience or feel.

Lucifer’s premise identifies the subject of the devil and the condition of God, who wants to see Lucifer defeated by the player to propel the process of what the player should experience. The definition of the genre to be an adventure/action game gives the team an idea of what kind of feeling Lucifer likes to convey.

Although, what commonly happens when you proceed from a concrete blueprint of a genre and a story structure is that you let the premise unite the minds. This creates a certain spatial distance to the narrative and cognitive core to the building of an engaging and dynamic game system. In the quest to reach the core mechanics to control the pacing of the motivating engine of learning, the designer will then have to break down the structures into smaller pieces of beats, units, and actions that form mechanics.

By keeping a curious mindset, the core to control the motivating and engaging forces is usually found. From breaking down a story structure into the mechanics which one switches in between as to set the rhythm of the pace, one lets the dramatic story structure construe the components, which sets the intensity of the engagement. The mechanics of exploration (2) would not signal any inconsistencies when proceeding from a story structure as it handles the results from understanding (3). Although, the narrative keys of taking perspective and position in relation to the goal regarding the Style and Form could do just that. Depending on the number of iterations to trace the core of the motivating engine of learning as to merge the story structure with the mechanics, the narrative system of logic, space and time will question if the hands-on process is adequate to meet the media-specific elements of the game.

The process of breaking down a structure into pieces does not contain any pitfalls in itself. However, what could become a constraint is if the premise unites the minds instead of thoughts and feelings. As it exposes beliefs, experiences, and expectations that could result in differing conceptions about the ultimate goal the learning-based approach may be put at risk.

Most of the narrative and cognitive pitfalls occur in the interface of going from a vision to the hands-on phase of realizing a goal because the invisible hierarchy of thoughts and feelings easily becomes a constraint to the process. We can keep a wide range of goals in mind that are categorized and ranked based on our subjective needs, beliefs, experiences, desires, expectations, and conventions. This means that the ultimate goal of an adventure game could be perceived in so many ways depending on the specific roles, tasks, and responsibilities assigned to them who work in the production.

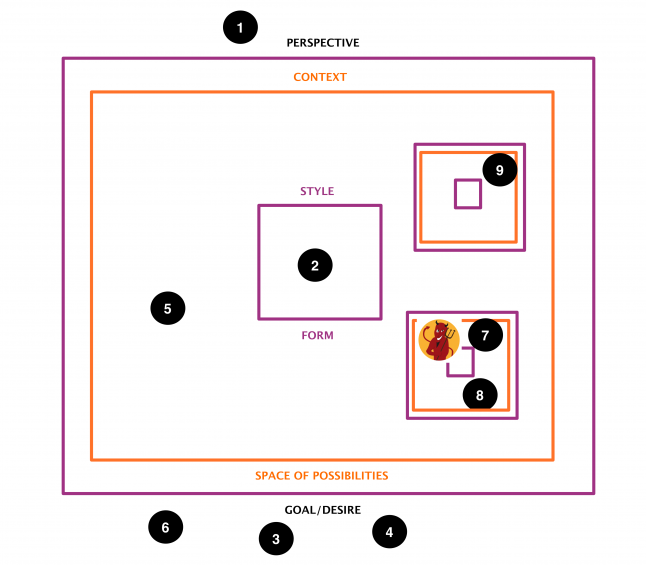

To give an example of how the mindset of learning handles the challenge of organizing a hierarchy of interest that could confound the possibility to define the ultimate goal to meet the players, I will make a "6th-grade move” of Lucifer. By changing the keys of perspective, position and goal we can make Lucifer the boss of the company whose focus is on earning fame and fortune from making games.

If we let the team (1) be attentive to the interruption of the flow from how the mechanics of exploration (2) processing the results from the exploration of the desired goals (3 and 4), the narrative keys and the mechanics will indicate a new goal to be on fame and fortune. The inconsistency from the new goal (6) and how it adds to the space of the game (5) will call upon the team’s attention to identify a changed perspective and position on Lucifer (7).

What the team needs to do is to rank the goals so as not to breach “the contract of trust,” which unites the minds and creates a bond with the players. If the desired goal can’t be reciprocally shared with the players, it needs to be subordinated to the goals that unite the minds and emotions.

By organizing the goals (3, 4, and 6) and the perspective and positions (1 and 7), the team (1) can distinguish two contrasting systems: Lucifer’s “business system” (7 and 6) and the “game system” (1, 3 and 4).

.png/?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)

The two contrasting systems above are not in conflict as they share the same mechanics of exploration (2). The shared mechanics make it possible to simultaneously explore each space of possibilities, the game (5) and the “business” (8), to see how they reach the desired goal of understanding (3) an engaging and dynamic game experience (4). However, what the team needs to do is to rank the systems and make Lucifer's "business system" subordinate to the "game system", which can be explained by the goal regarding the player's experience or feelings (9).

Assuming Lucifer still shares the learning-based approach to the task he won't constitute a risk to the process by mixing beliefs from an organizational hierarchy of interests with the ranking of the cognitive and narrative systems.

The goal of what the player should experience or feel (9) only concerns the space of the game (5) so if the team decides that the player should experience uncertainty or fear, it is not a goal the “business system” should pick up. It is here that the interface between reality and fiction can be discerned. It is also here that the “contract of trust” of reciprocally shared goal shows. Having created a bond to the player, you need to take care of the trust across all systems and where the goal of what the player should experience or feel should be the ultimate goal that unites the entire concept.

Final scenario - turning constraints into possibilities by staying close to the core

Since real-life activities share the same narrative and cognitive forces employed by a narrative constructor creating an engaging and dynamic space in fiction, a narrative and cognitive constraint, in reality, could be converted into a possibility in fiction. In common language, we call it inspiration.

Inspired by Lucifer and staying close to the core to how our thoughts and feelings work, the team (1) can make a 6th-grade move of the dynamic forces of Lucifer and convert the narrative and cognitive forces of the two contrasting systems to become a part of Lucifer’s premise - to make a game set in hell where the player is sent by God to defeat the devil.

From the result of testing and adjusting imaginative hypothesis (2) the team can evolve the premise as follows:

An identified subject of the devil (7) who desires to gain fame and fortune (8), propels the process (2) of an engaging and dynamic experience (3 and 4) to defeat Lucifer (6).

By holding on to the ranking of the desired goals in the following order: 3, 4 and 6, so as to stay close to the cognitive core, the team (1) can open a new frame from which they take perspective and position (1) as to identify a player system (9) and convert the so-called Lucifer’s “business” system into a devil system (7 and 8).

The team has given meaning to the game (5) by creating two systems. If the team (1) has stayed close to how our thinking and learning work they will be able to “hand over” their position to the player and let the player take their perspective to defeat the devil (6). The mechanics of exploration (2) provides the system of the devil (7 and 8) with a behavior, rules, and goal that can act and react on the players’ intentions and actions (9). In this way, the mindset of the team (1) unites the minds and creates a bond to the players (9) “to get the devil”.

The design process is initiated.

Based on a narrative and cognitive core, the team (1) can proceed from the core to how our thinking works to build a structure in line with the media-specific style and form of the game. They will be able to let the mechanics of exploration (2) generate results that unfold the elements that are to be converted into tangible parts of engaging and dynamic experiences. The simple blueprint of the narrative and cognitive core above keeps the possibilities of the space (5) to evolve along with the elaboration of the premise. The actions depicted in the image above of “to get” will also evolve as the team proceeds towards the desired goal.

So far I haven’t defined what the player should feel. This will be elaborated on in the next chapter, where I will engage the team (1) in the meaning making (narrative construction) of the player’s experience and feelings.

Consider joining the team at this stage of the process. When asking what the team’s desires are you should listen to how the team describes the premise as it will tell you how to:

Discern constraints of beliefs, meanings, and preconceptions in the design process.

Build a bond with the player in the exchange of thoughts and feelings.

Distinguish and tune the different grades of attention and engagement and their effects on motivation and emotions.

Present information before the receiver’s senses and balance the duration of the cognitive activities and the effects on the emotions and actions (see also Part 3, Narrative bridging on testing an experience).

As it is together that we learn, if you have any questions, don’t hesitate to contact me via Twitter @gyllenback or write to:

Until next time, take care and stay curious!

Katarina

Illustrations by Linnea Österberg (The team and horses).

Illustrations by Emese Lukács (The cavemen and the devil).

References:

Gyllenbäck, K, Boman, M (2010). Narrative bridging. Design Computing and Cognition ’10. Edited by John S Gero. SpringerLink. pp 525-544

Gärdenfors, P., Lombard, M., (2017). Tracking the evolution of causal cognition in humans. In the Journal of Anthropological Sciences 95. p.219-234

Reference to the concept of learning and narrative construction:

Bruner, J. (1991). The narrative construction of reality. Crit. Inq. 1, 1–21. doi: 10.1086/448619

Bruner, J. S. (1990). Acts of Meaning. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (2009). Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Return to:

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle

Part 5, Putting into play - On organizing thoughts and feelings

Or visit Narrative Construction:

Part 1 Putting into play - A model of causal cognition on game design.

Part 2, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective I

Part 3, Putting into play - On narrative from a cognitive perspective II

Part 4, Putting into play - How to trigger the narrative vehicle

Part 5, Putting into play - On organizing thoughts and feelings link

A short guide to the 7-grade model of reasoning

An introduction to Narrative bridging

No animals were harmed in the making of this post.

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like