Nineteenth century artist Gustave Caillebotte showed how old methods could be used to tackle new subjects in a stunningly expressive way. Game devs can do the same, says columnist Katherine Cross.

“Do nudes, but do beautiful nudes, or don’t do them at all!”

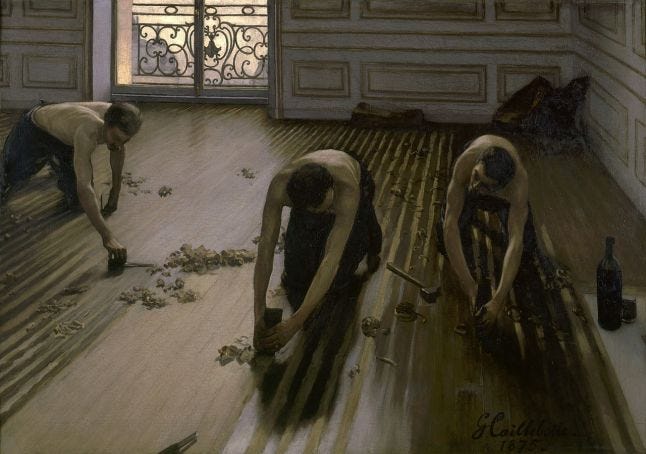

Thus thundered one art critic’s response to Gustave Caillebotte’s (1848-1894) The Floor Scrapers. The outrage mirrored the response of the Salon jury--the then guardians of French elite art--who rejected the painting as unworthy.

When I first laid eyes on The Floor Scrapers it occupied a place of prominence at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., on loan from the Musee d’Orsay in Paris. The story of the artist scorned in life and revered in death is one of our most cherished cliches; there’s little original about it, but Caillebotte’s particular case is interesting for game developers to study.

Caillebotte is often grouped together with the avant-garde Impressionists of whom he was both an admirer, a patron, and even a personal friend, but he took the period’s style in a unique direction. While Caillebotte’s friends were moving away from naturalism--i.e. paintings that attempt photorealism in their representations-- he stuck to the classical forms, striving for crisp and faithful images.

What set him apart, and what made him an object of scorn in the elite French art world was that he took on a completely different subject. The eponymous Floor Scrapers were not Classical gods or heroes, nor emperors, nor a study of an elite family; they were ordinary workingmen who were literally hewing at modern Paris.

Caillebotte’s Les raboteurs de parquetâAU (The Floor Scrapers)

What made Caillebotte’s work unsettling to those already disdainful of the Impressionist wave was that unlike his contemporaries, Caillebotte was showing how old methods could be used to tackle new subjects in a stunningly expressive way. None of Monet’s hazy studies in color for him, nor Seurat’s pointillist moods; he painted modern Paris as if he were painting a Greek god.

What does this have to do with game design? Consider the fact that the methods and visions of games like Journey, Lovers in a Dangerous Space Time, Gone Home, Sunset, and Dear Esther all use tools derived from the "triple-A," big-budget market--the domain of tradition-bound games--to tell new stories about new people, in the process creating something stunningly different.

In addition, Caillebotte can teach us something about a subject I had discussed in a previous column: how to make cities come to life and become characters/subjects in their own right.

"What made Caillebotte’s work unsettling to those already disdainful of the Impressionist wave was that unlike his contemporaries, Caillebotte was showing how old methods could be used to tackle new subjects in a stunningly expressive way."

***

Video games are never far from my mind when I’m in an art gallery; as much as we (rightly) harp on how new and revolutionary this medium is, we can sometimes forget that in crucial ways, we have been here before and that the past can be a useful field-guide to the present.

The rage that met Caillebotte’s use of anonymous working and middle class subjects in his art is quite analogous to that which still greets games which make people of color, the poor, the mentally ill, into their protagonists.

Caillebotte’s use of classical, naturalist techniques showed that there were new tricks in old methods; it made it impossible to argue that the “degradation” of art was merely the province of those moving away from naturalism. Similarly with video games, many new indie games nevertheless show that traditional graphical design can always be bent in new and insightful ways.

Tale of Tales’ Sunset (whose name now sadly says as much about the company itself as the game) provides us with an interesting case study. The developers did not, originally, want to tell their next tale with triple-A representational and naturalistic design but came around to doing so in order to make Sunset more approachable to people who might otherwise be put off by more avant-garde styling.

The game still sold poorly and was marred by occasional graphical glitches and poor performance; hopes for a broader audience fizzled.

Tale of Tales' Sunset

Tale of Tales' Sunset

But as a work of art, the game remains a resounding success. Like Caillebotte’s best work, it used its traditional medium to tell a story about an ordinary life rather than an idealized hero. It is the story of someone that most video games would barely regard as an NPC much less a playable protagonist.

Sunset's Angela Burnes, a young black engineer forced to be a housekeeper in a foreign country, is not unlike the wood scrapers or the titular character of Caillebotte’s Interior, Woman at the Window. She's a figure summoned from the masses of modern society for artistic consideration, whose situation says as much about her as her body. Angela Burnes’ tale is about the meaning of housekeeping, the relationship of a working class woman to someone far more powerful than her, and the life of a person during an age of revolutionary war, holding onto the ordinary in the midst of history’s pageantry.

Other video games would make the protagonist someone standing far beyond the windows of Burnes’ world: the game would be about some hotshot rebel, scrapping in the streets with government troops. Sunset's perspective shift puts the focus elsewhere, telling a different story about life in wartime and how the small inputs of an otherwise disregarded person can make a difference all on their own. Burnes' story is an echo, the life inside the buildings that populate an FPS' background.

It mirrors the shift from the heroic or idealized figures of earlier art to the subjectification of ordinary people in 19th Century art. In games we’re slowly, grudgingly moving from our own divinity figures--that of the grizzled (space) marine--to a variety of other, previously ignored characters.

You could have told this story in Twine, certainly, or in a fuzzier, less naturalistic fashion with the magical realism that is video games' native expression. But through the use of high graphical tools, the sharp relief into which Burnes’ life was cast allowed the player to empathize with her as they pored over the lovingly rendered odds and ends of her employer’s life. He, too, is in the distant background, like one of the umbrella wielding figures in Caillebotte’s Paris Street, Rainy Day, and yet you learn so much about him because of the game’s sharp graphical focus. Through dispensing with elaborate metaphor and impression, the reality of Angela Burnes’ life comes through with unmistakable clarity from the mist.

***

Caillebotte's Paris Street, Rainy Day

In the same way, a city can come to life too. Caillebotte’s foremost subject throughout his sadly abbreviated career was Paris itself. To look at his most famous painting, Paris Street, Rainy Day, seen above, is to realize that the primary subject is not the well dressed couple in the foreground--they appear there as if by chance, uninterested in the painter, unposed, caught as a moment in time not unlike if they were photographed--but the city beyond, which is stable and unyielding unlike the random, anonymous passersby who populate it.

Painting at this time began to become useful as a catalog of the everyday, something less common in eras past when artists were meant to capture either highly staged scenes or religious and mythical ones.

That attention to the quotidian is what gives Caillebotte’s Paris some character. It almost always begins from the Hausmannisation of the city; the rationalized urban plan of the mid 19th Century that gave Paris its now famous broad streets and boulevards, and made way for the railroads; straight lines, perspectives, modern materials and facades, traffic flows, all tell Paris’ tale.

What can game developers learn from this? The most lively representations of cities must begin from one defining feature that then undergirds everything else. Whether your game is set in a fictional city or a representation of a real one, look for what it is that gives the city its character. Not just landmarks, but the marrow of the city itself. For Caillebotte, what stood out to him about Paris was its modernized look and feel. The mathematical angles of Baron Hausmann’s boulevards and intersections tell their own story that also serves as a documentation of mid 19th century Paris.

Similarly, for Orgrimmar, the fact that this signature World of Warcraft city is hewn into a canyon is used again and again to provide attractive and distinctive vistas--a city of stone very different from, say, Stormwind’s marble (whose castle also sets the tone for the entire city). Consider also the Undercity as a Nightmare Before Christmas-style urbanscape that begins from a single theme: it�’s located in a crypt. What if an anarchist squat were a whole neighborhood in Berlin? Shadowrun: Dragonfall has the answer.

One single theme can drive your portrayal of an entire city, spooling it out into a character in its own right.

A theme can be seen as the “key” in which your city is composed, which is essential for making a city a memorable component of a work of art, be it a video game or an oil painting. Crucially this means that even deliberately dreary or flat cities can still have character; just as Caillebotte made modern urban planning into a “character” so too can game devs make intentionally rationalized or dull places into living members of the game’s environment. It is all a matter of finding the guiding theme to emphasize and then iterating with it.

Just as Caillebotte’s work emphasized the use of vision--be it his own, his subjects’, or ours as the viewer--videogames do the same thing. We all see through the painter’s eye or the designer’s eye, out onto a world populated by stories; make them interesting ones.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like